Trump made history by becoming the first U.S. president to explicitly call for fiscal dominance.

Written by: Byron Gilliam, Blockworks

Translated and organized by: BitpushNews

Once upon a time, Federal Reserve chairmen could freely "lecture" politicians about their irresponsible spending habits; it was a delightful era.

For instance, in 1990, Alan Greenspan told Congress he would lower interest rates, but only if Congress cut the deficit.

In 1985, Paul Volcker even provided specific numbers, telling Congress that the Fed's "stable" monetary policy depended on Congress cutting about $50 billion from the federal budget deficit. (Ah, that was indeed a time when $50 billion in federal debt was not just a rounding error.)

In both cases, the Fed chairmen subtly threatened Congress and the White House with the risk of recession: you have a nice economy now, it would be a shame if something went wrong.

However, the situation has reversed now, with U.S. President Trump "lecturing" the Fed about interest rates.

In recent weeks, Trump has expressed views that the federal funds rate is "at least 3 percentage points too high," insisting that "there is no inflation," and mocking Fed Chairman Jerome Powell as "Too Late Powell."

This is also a form of pressure: you have a nice degree of central bank independence…

During his first term, Trump also lobbied for lower interest rates. Like almost all modern U.S. presidents, he wanted the Fed to stimulate the economy.

However, this time, it goes far beyond that: Trump wants the Fed to finance the deficit.

The confrontation between Trump and Powell is ostensibly about the current level of interest rates (the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is keeping rates unchanged today, which will likely displease the president).

But what the president has been threatening is "fiscal dominance"—the state where monetary policy is subordinate to the demands of government spending.

"Our interest rates should be 3 percentage points lower than they are now, saving the country $1 trillion a year," the president recently wrote on Truth Social in his signature casual capitalized style.

By repeatedly making such statements, Mr. Trump has made history as the first U.S. president to explicitly call for fiscal dominance.

But he is certainly not the first to acknowledge this possibility.

When Volcker and Greenspan threatened Congress with interest rate hikes, it brought to light the usually hidden connection between monetary policy and fiscal policy.

It worked for them: both Fed chairmen successfully used the threat of recession to compel Congress to address the issue of deficit spending, setting a hopeful precedent.

But this strategy seems unlikely to work this time.

Chairman Powell frequently warns of the risks of rising deficits, even explaining that higher deficits could mean higher long-term interest rates.

But it is hard to imagine he would issue a clear threat like Volcker and Greenspan did—perhaps because he knows he is in a clearly weaker bargaining position.

In the 1980s, the most concerning effect of raising interest rates was recession, and the Fed was willing to take that risk to prompt Congress to change its extravagant spending habits.

At that time, lawmakers faced an expanding defense budget and a stagnant economy, both of which seemed manageable.

The federal debt was only 35% of GDP, which also appeared manageable.

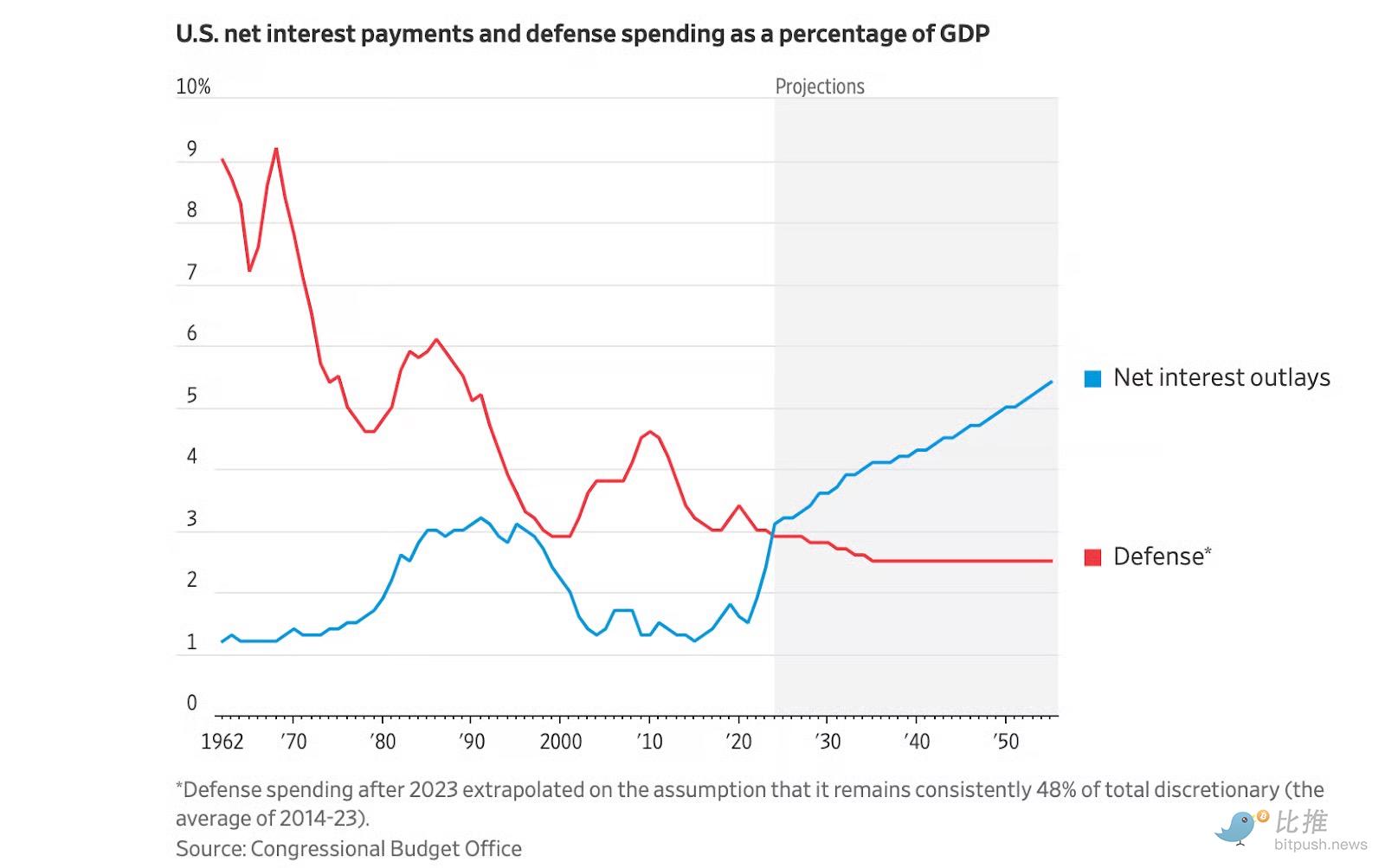

Now, federal debt is 120% of GDP, and U.S. spending on interest payments exceeds defense spending:

Chart: The rapidly rising blue line represents the proportion of federal debt interest payments to GDP, far exceeding defense spending.

The rapidly rising blue line in the chart may now be the biggest budget issue.

This puts the Fed in a dilemma: it wants to use interest rate hikes to "cure" the government's fiscal problems, but the scale of government debt is so large that raising rates could become "poison," worsening the fiscal issues.

Of course, the Fed could take the risk.

But if raising rates leads to further increases in the deficit, who will blink first: the Fed or the White House?

Before answering, consider that 73% of federal spending is now non-discretionary, while it was only 45% in the 1980s.

If one believes the Fed can win a showdown over the deficit, it is tantamount to believing Congress is willing to make significant cuts to non-discretionary spending like Social Security and Medicare.

That seems, well, unbelievable.

Especially now, with a president who appears completely unfazed by the nation's growing debt situation.

This may stem from his experience as an over-leveraged real estate developer in the 1990s.

"I think it's the bank's problem, not mine," Trump later wrote about his inability to repay debts, "What the hell do I care? I even told a bank, I told you, you shouldn't have lent me money, I told you that damn deal wouldn't work."

Now, as president, when Trump tells Powell that interest rates should be lower, what he really means is that the national debt is the Fed's problem, not his.

He is not wrong.

"When debt interest payments rise and fiscal surpluses are politically unfeasible," wrote former U.S. Treasury economist David Beckworth, "there must be sacrifices. These sacrifices are more debt, more money creation, or both."

Yes, the Fed could resort to Volcker/Greespan's old tricks by threatening Congress with higher rates.

But Powell probably knows that if he really does that, it will only exacerbate a problem that may ultimately require the Fed to solve—and accelerate the timeline for being forced to address it.

"If debt levels are too high and continue to grow," Beckworth explains, "the Fed's responsibility becomes to accommodate—by lowering rates or monetizing debt."

He warns that this is the real existential threat to the Fed, not Trump: "When a central bank is forced to accommodate fiscal demands, it loses its economic independence."

Beckworth still holds out hope that it may not come to that.

Maybe it won't. We have seen how unpopular inflation is, so if another round of inflation occurs, voters may force lawmakers to address the deficit.

But he feels despair that focusing on Trump's call for lower rates is a distraction: "What we are witnessing is less about Trump himself and more about the growing and unavoidable fiscal demands being placed on the Fed."

Trump is the first to explicitly make these demands, probably because he knows that the current fiscal policy of the U.S. government is unsustainable.

But everyone knows this, even the government itself.

Now the only question is: who will deal with it?

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。