Original Title: We Are Not Onboarding Institutions (for Now)

Original Author: @PossibltyResult

Translation: Peggy, BlockBeats

Editor's Note: High leverage and low buffers are the core designs of most current cryptocurrency derivative trading platforms. This model caters to retail investors' preference for leverage, but also makes deleveraging the primary means of addressing risk, contrasting sharply with traditional derivative markets that rely on substantial insurance and risk waterfalls. This article points out that the difficulty for institutional funds to enter the market is not simply a matter of will, but a result of market design and risk structure through a comparison between cryptocurrency trading platforms and traditional markets like CME.

This article argues that serving retail and serving institutions inherently means different trade-offs. In an on-chain environment, even without off-chain recourse, trading platforms can still improve risk management by lowering leverage, increasing buffers, and enhancing transparency.

Here is the original text:

“In this world, I will bind myself... to serve you, to wait for you; when we meet in the afterlife, the reward will be settled.” — The devil in "Faust"

Abstract

Today's cryptocurrency derivative trading platforms (whether on-chain or off-chain) were not initially designed to serve institutional investors. They prioritize high leverage demands (which are extremely appealing to retail investors), rather than limiting tail risks (which are of primary concern to institutions).

Despite some practical barriers to evolving on-chain trading platforms toward "institutional-level risk management" (such as a lack of off-chain recourse mechanisms), significant improvements can still be made if trading platforms are willing to "put their own money on the line" (using their own capital as risk buffers). Additionally, there may be more creative risk mitigation methods, which will be briefly discussed at the end of the article.

Even if on-chain trading platforms ultimately choose not to serve institutions, open-source and verifiable deleveraging protocols are still much friendlier to retail investors than opaque, ad hoc centralized deleveraging mechanisms (such as Robinhood during the GME saga).

Introduction

It is well known that cryptocurrency traders love leverage.

Trading platforms certainly understand this and build products around this demand. However, there exists a constant tension: the higher the leverage, the more significant the amplified losses; the less collateral available to cover those losses, the higher the risk of insolvency faced by the trading platform.

Inevitably, "insolvency" is a situation trading platforms must avoid at all costs. Once they can no longer honor user withdrawals, the trading platform is essentially declaring death — no one will use it again. Therefore, trading platforms must find a compromise that reduces the risk of bankruptcy without sacrificing the appeal of high leverage.

We have recently witnessed the consequences of such mechanisms. On October 10, the cryptocurrency market dropped sharply in a very short time. To avoid insolvency, the Auto-Deleveraging (ADL) mechanism was triggered: some profitable positions were forcibly liquidated at worse than market prices to cover and close corresponding bankrupt loss positions. At the cost of these profitable traders, the trading platform was able to maintain solvency.

If viewed as a compromise arrangement — with one side being the traders desiring high leverage and the other side being the trading platform unwilling to bear excessive risk — this is not inherently problematic. It resembles a strategic choice: both sides get what they need, and the trading platform can retain customers while avoiding its own losses or being forced to shut down.

The real issue arises here: does such a mechanism allow the trading platform to onboard another type of trader — those highly desired "institutions"?

Broadly speaking, institutions are commercial entities with substantial capital and stable order flow that are accustomed to trading derivatives on regulated exchanges in the U.S. In these markets, leverage is strictly limited, and auto-deleveraging is only the last line of defense; before this, clear rules and tens of billions in insurance funds provide a buffer.

When your goal is 100 times the return, it may not matter to backstop others' bankruptcy risk; but when your goal is merely 1.04 times per annum, tail risk becomes crucial.

Why Does This Matter?

As the industry continues to grow, trading platforms hope to grow alongside it. However, the existing pool of crypto-native traders has a cap, and there is ultimately limited room for growth. Thus, trading platforms must look towards new sources of incremental growth.

Ideologically speaking, this endeavor is meaningful. A programmable, verifiable, self-custody financial system represents a breakthrough from zero to one, bringing forth entirely new trading methods and financial product combinations, and exhibiting superior transparency and (in extreme cases) reliability compared to traditional systems. Integrating these advantages into the existing financial system should be the source of next-stage growth.

However, to genuinely attract these users, we must build a risk management system that aligns with their risk preferences. To ascertain how to improve, we first need to dissect a core question: how does risk management operate in the traditional financial system, particularly regarding "bankruptcy risk"? How is it fundamentally different from the practices of cryptocurrency trading platforms?

There has been a substantial amount of reflection on the deleveraging mechanisms surrounding cryptocurrency trading platforms, but discussions have largely focused on how to design "better ADL mechanisms." This is certainly valuable but overlooks a higher-order question: why does deleveraging operate in this manner in the cryptocurrency market? Where does this difference originate? How should it be addressed in the future?

These questions also deserve serious consideration.

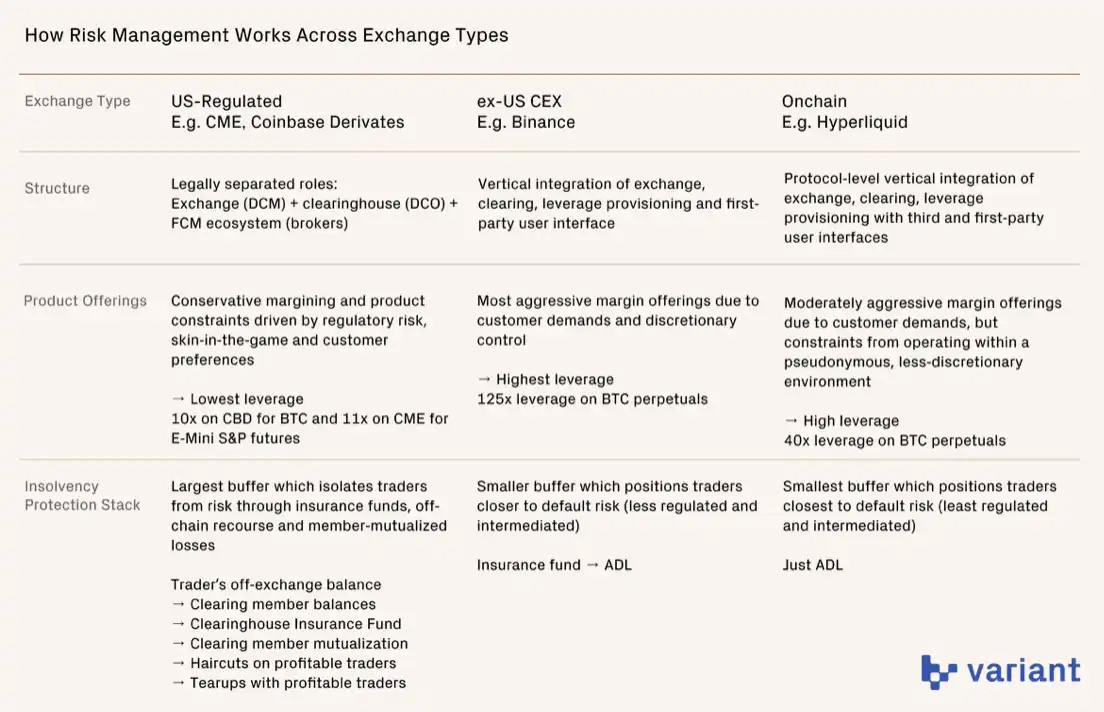

Dissection of different trading platform designs in crypto markets versus traditional finance

Deleveraging Mechanisms in Traditional Finance

In cryptocurrency derivative trading platforms, forced liquidation, haircuts, or direct contract tear-ups are often the first line of defense against insolvency; whereas in traditional derivative trading platforms, these measures are precisely the last line of defense.

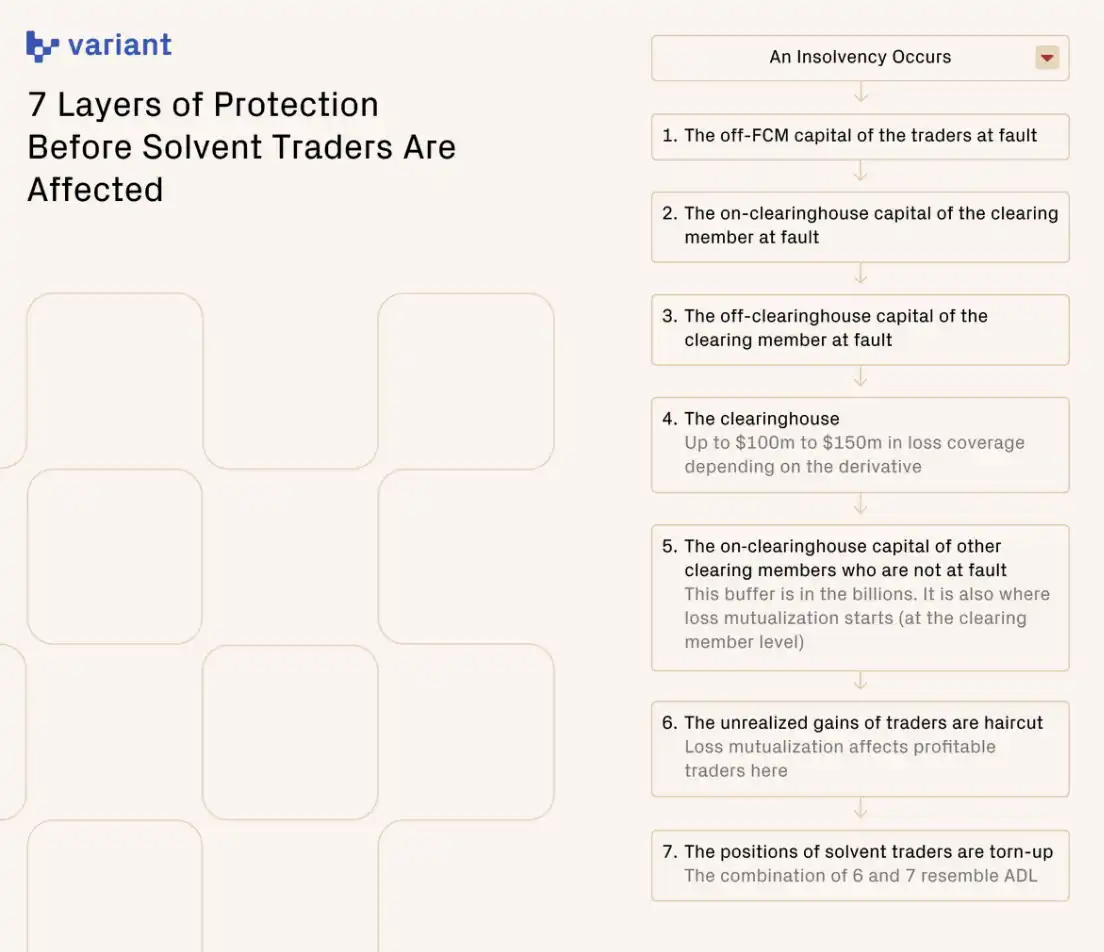

Take CME as an example; when a bankrupt position arises, the "trading platform" will bear and distribute immediate losses through a mechanism known as the risk waterfall. This mechanism clearly stipulates which market participants take on risks in what order.

However, it is especially important to note that in this context, the "trading platform" is not a highly integrated single platform like in the cryptocurrency market. Instead, the functions of leverage provision and trade settlement are modularized, fulfilled respectively by clearing members and the clearinghouse.

Clearing members (also known as Clearing FCMs) are typically well-capitalized, strictly regulated institutions (such as banks). They serve as the primary interface for users entering the market: on one hand, they provide leverage and hold clients' collateral; on the other hand, they open accounts on behalf of clients at the clearinghouse, thereby gaining access to the trading platform.

The clearinghouse is the core entity responsible for trade settlement. Once trades have been matched on the trading platform, the clearinghouse intervenes between counterparties, acting as "the buyer of every seller and the seller of every buyer," thus assuming the role of central counterparty to ensure smooth settlement.

In stark contrast to the cryptocurrency market: in traditional financial systems, profitable traders hardly ever bear the costs of others' bankruptcies in the first instance. Clearing members and the clearinghouse provide a substantial buffer through the risk waterfall mechanism to protect still-insolvent participants from the direct impacts of fellow failures.

Under CME's risk waterfall mechanism, the order of loss coverage is as follows:

The most striking point is that while two systems seemingly aim for the same objectives, they handle the same situations in fundamentally different ways.

At CME, profitable positions are safeguarded by a buffer of tens of billions before being affected; whereas at most cryptocurrency derivative trading platforms, such buffers are nearly nonexistent or completely absent.

Motivations Behind Market Design

This naturally raises a question: why is this the case?

Reason 1: Different Target Users and Incentive Structures

Retail investors in the cryptocurrency market are clearly more concerned with obtaining high leverage than the risks brought about by Auto-Deleveraging (ADL). Due to the propensity for high leverage to significantly increase insolvency probability, if trading platforms must bear bankruptcy costs themselves, they are unlikely to offer such high leverage to retail investors.

In stark contrast, institutional investors place extreme importance on the tail risks faced by their positions. If every gap in funding directly impacts their positions, they often choose not to use that trading platform.

For instance, suppose a hedge fund is executing a delta-neutral strategy, where the short leg is completed on a perpetual contract trading platform. If ADL is triggered at that moment, the short position will be forcibly closed, leaving its long position exposed to market risks without hedging protection.

For these traders, whose primary focus is risk management, the availability of 125 times leverage is not significant; what's important is reliable protection in extreme situations. Thus, institutions often avoid trading platforms that cater to retail groups they do not wish to "cohabit" with, thus bearing extra risks.

From this, we can conclude that if cryptocurrency derivative trading platforms hope to onboard institutional users, they must re-evaluate their risk management policies.

The combination of "thin buffers + high leverage" clearly conflicts with the goal of "building institutional-grade financial infrastructure"; yet it perfectly fits the genuine needs of many retail investors.

Therefore, the risk structure a trading platform offers essentially depends on who it seeks to serve.

Reason 2: Absence of Recourse in Pseudonymous Environments

The second reason is that in pseudonymous, on-chain environments, the risk waterfall mechanism is inherently "thinned out" due to the near-absence of effective off-chain recourse measures.

In the CME system, when a trader's losses cannot be fully covered by their margin, the clearing member can demand additional margin from the trader; if the clearing member's losses remain uncovered, the clearinghouse can also seek funds from the clearing member.

Now try to imagine: how would you seek to recoup funds from a wallet identified solely by a hexadecimal address, with assets fully self-custodied, outside of the trading platform?

The answer is: you simply cannot.

Once off-chain recourse cannot be relied upon, the buffer layer constituted by traders and clearing members ceases to exist. In this case, the only barrier between insolvency and "healthy traders facing mandatory deleveraging" is the insurance funds reserved within the protocol.

Simultaneously, this structure also makes the trading platform itself reluctant to put its own funds at risk — because in any risk waterfall, the trading platform is first in line to bear losses.

It should be noted that this limitation constitutes a fundamental barrier only to completely pseudonymous account systems.

Whether on-chain or off-chain, as long as trading platforms can implement a certain degree of off-chain recourse in their system design, they can still leverage these mechanisms to significantly expand the buffer space before losses begin to be mutually absorbed.

Of course, for certain traders, this structure may actually be desirable. Because their maximum loss is strictly limited to the collateral submitted to the trading platform, risks are clearly isolated.

However, it is essential to emphasize that this is not unique to cryptocurrency markets. In traditional financial systems, traders can equally negotiate similar arrangements with brokers.

It’s Not All Bad for Retail Investors

Not everything is entirely pessimistic. Optimizing around retail investors is not inherently a bad thing. At least, in an on-chain and open-source context, deleveraging mechanisms can be transparent, verifiable, and strictly follow pre-agreed rules.

And this is precisely what many retail trading platforms lack. Here are two representative examples:

Robinhood and the Aftermath of the GME Squeeze

The most notorious instance of an opaque, ad hoc deleveraging event occurred after the price surge of "meme stocks" like GME and involved Robinhood.

Because stocks are not settled instantly, Robinhood, as a broker and also a clearing member of the National Securities Clearing Corporation (NSCC), had to manage the risks of counterparty defaults leading to settlement failures. Similar to CME's clearing members, NSCC requires clearing members to post margin based on their unsettled positions.

During the GME surge, Robinhood users massively bought in, leading to a rapid increase in its unsettled balances. In response, NSCC significantly raised Robinhood's margin requirements to ensure it had enough capital to settle.

This, in turn, created liquidity pressure for Robinhood. If buying continued to increase, Robinhood might not be able to meet the new margin requirements.

To reduce risk and shrink unsettled buy orders, at the height of the market volatility, Robinhood temporarily shut down retail buying, forcing users to sell and thereby lowering their unsettled balances.

This event revealed two core issues:

The deleveraging mechanism is temporarily and retrospectively decided

Traders were not made aware in advance that Robinhood would suspend buying, so they were unable to adjust positions in advance to mitigate risks.

The systemic risk of T+2 settlement cycles

The longer the settlement cycle, the more easily unsettled positions stack up, leading to liquidity crises when clearinghouses demand additional margins.

In the aftermath of this event, the SEC shortened the settlement cycle to T+1.

Centralized Cryptocurrency Trading Platforms Post October 10

After the incident on 10/10, rumors circulated on platform X that some trading entities had "side agreements" with trading platforms that spared their positions from being subject to ADL.

If true, this means that traders without such agreements were transparently subjected to prioritized forced liquidations, clearly at a disadvantage.

Whether these institutions really obtained explicit ADL protection or not, this event highlighted the issues of transparency and incentive structures within centralized cryptocurrency trading platforms.

In comparison, Binance at least drew on $188 million from its $1.23 billion insurance fund before triggering ADL. However, the issue lies in the fact that the scale of this insurance buffer was not disclosed in advance.

Admittedly, trading platforms might choose confidentiality for security reasons to prevent manipulation by counterparties, but this level of transparency may still fall short of expectations set by large institutions.

Addressing Issues Through On-Chain Constructs

One alternative solution could be to replace reliance on trusted third parties with on-chain systems to ensure the transparency and enforceability of deleveraging conditions.

When deleveraging mechanisms are on-chain and the code is open-source: the rules for deleveraging must be explicitly written into the protocol in advance for nodes to participate in consensus; T+1 settlement can be replaced with nearly instantaneous settlement based on the finality of the protocol.

Conclusion

Most current cryptocurrency trading platforms are not designed for institutional adoption. They prioritize offering high leverage at the cost of higher mandatory liquidations and shared loss risks.

This trade-off is extremely attractive to retail investors but significantly limits trading platforms' ability to attract institutional capital.

Despite the real difficulties faced by on-chain trading platforms as they move toward institutional-level risk management (such as the lack of off-chain recourse), significant improvements can indeed be achieved by lowering maximum leverage and providing more capital buffers before ADL.

This also points to a more realistic future: different on-chain derivative trading platforms will serve different types of users.

Institution-focused trading platforms can construct insurance mechanisms that genuinely involve their own capital and use leverage limits to reduce the compensation risks they need to bear.

In fact, this differentiation is already appearing in the off-chain cryptocurrency derivative market: CME, Coinbase, Hyperliquid, and Binance are each serving different user groups through varied architectures and risk management practices.

Additionally, there are less intuitive, yet valuable paths for exploration. For instance: introducing an optional "broker layer" (similar to clearing members) to provide traders with additional leverage or protection. The trading platform itself would still provide base leverage and guarantees, while more precise risk adjustments are outsourced to specialized brokers. This could even support "margin calls" as an alternative to automatic liquidations.

To some extent, this model already exists in "off-chain ways" — for example, users can borrow USDC from lending protocols and use it atomically for perpetual contract trading.

Even if on-chain trading platforms ultimately opt not to cater to institutions, there are still ample reasons to remain optimistic. Open-source on-chain trading platforms serve as a powerful alternative to opaque, centralized deleveraging mechanisms. Within this system, traders can both understand "how the trading platform is theoretically supposed to operate" and have confidence that the actual operation follows the code itself.

Thus, traders can better manage risks and reduce sudden unforeseen events.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。