Authors: Miles Jennings, Scott Duke Kominers, and Eddy Lazzarin, a16z

Compiled by: Glendon, Techub News

As the activity and innovation surrounding token-based network models become increasingly vibrant, developers are contemplating how to differentiate between various types of tokens—and which type of token is best suited for their business. Meanwhile, consumers and policymakers are also trying to better understand the roles and risks of blockchain tokens in applications.

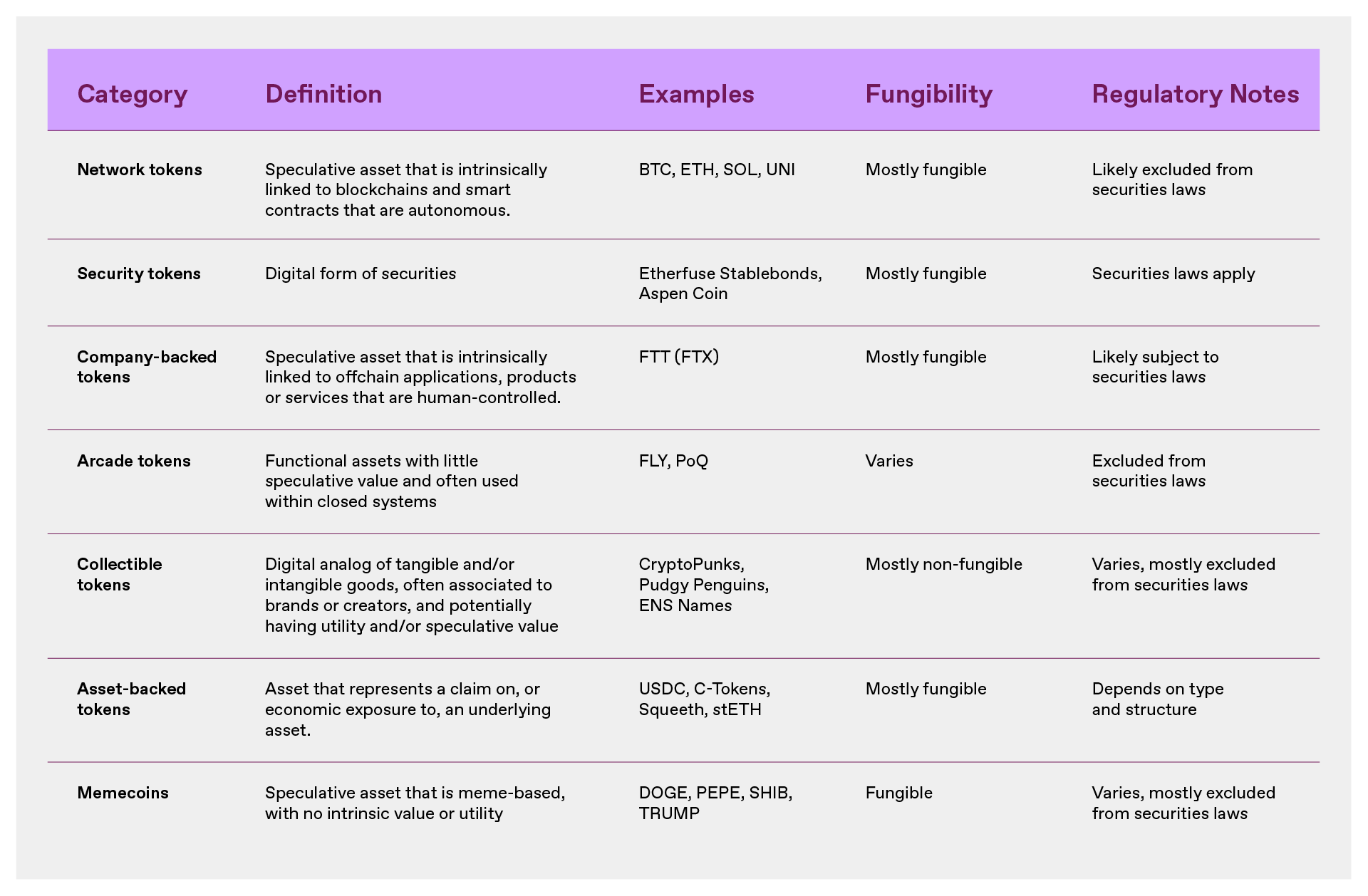

To help clarify token categories, this article provides definitions, examples, and a classification framework to understand the seven types of tokens that developers most commonly build: Network Tokens, Security Tokens, Company-Backed Tokens, Arcade Tokens, Collectible Tokens, Asset-Backed Tokens, and Memecoins.

Tokens and Their Characteristics

The essence of tokens is to enable true digital ownership.

More precisely, a blockchain is a decentralized computer made up of a network of individual computers that maintain a shared ledger—essentially a "cloud computer." Tokens are data records on these ledgers that can track quantities, permissions, and other metadata. The key point is that these data records can only be altered according to the coding rules of the blockchain, which can be used to grant enforceable rights.

Within this technical framework, many details influence design, functionality, value, and risk:

Programmability

Since tokens are embedded in software, they can be programmed to represent almost anything—any digital form or property record. This means tokens can be designed as Bitcoin-like digital value stores, Ethereum-like productive and consumable assets, collectibles like digital trading cards and game items, payment stablecoins like USDC, or even digitized stocks.

Rights and Circulation Attributes

Some tokens confer various rights (such as voting rights or economic interests), while others only allow for the use of products or network services. Some tokens can be freely transferred between users, while others are restricted; some tokens are fungible, meaning all units are equivalent, while others are non-fungible, representing unique individual assets (like trading cards or even the Mona Lisa).

These design choices are crucial because they determine whether a token is a good store of value or medium of exchange; whether it is a productive asset with intrinsic functionality and/or economic value; or whether it is essentially a worthless speculative tool. At the same time, the characteristics of tokens also directly affect their legal classification.

Therefore, whether you are a blockchain project developer, an investor, or an ordinary user of tokens, understanding token types is essential—never confuse Memecoins with Network Tokens. This article also aims to help investors eliminate this confusion.

Types of Tokens

Network Tokens

Network Tokens are fundamentally closely related to the programmatic functionality of a blockchain or smart contract protocol, and their value derives from this.

Network Tokens typically have built-in utility; they can be used for network operations, achieving consensus, coordinating protocol upgrades, or incentivizing network operation. The networks associated with these tokens usually (in most cases should) contain economic mechanisms that drive token value. These include programmatic buybacks, dividends, and other changes to the total supply of tokens through token creation ("faucets") or destruction ("sinks") to introduce inflation and deflationary pressures to serve the network.

Network Tokens can have trust dependencies similar to commodities and securities. Recognizing this, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) established a 2019 framework and FIT21 that stipulate when the decentralization of the underlying network mitigates these trust dependencies, Network Tokens will be excluded from U.S. securities laws. The core essence of decentralization is that the system can operate without human control (individuals, companies, or management teams).

Network Tokens are best suited for guiding the creation of new networks, allocating ownership or control of the network to its users, and/or ensuring that the network can self-fund for ongoing and secure operations. Examples of Network Tokens include BTC, ETH, DOGE, SOL, and UNI. In the context of smart contract protocols like Uniswap and Aave, Network Tokens are sometimes referred to as "protocol tokens" or "application tokens."

Company-Backed Tokens

Company-Backed Tokens are intrinsically linked to off-chain applications, products, or services operated by a company (or other centralized organization). The value of such tokens derives from this, essentially relying on the continued operation of a centralized entity.

Like Network Tokens, Company-Backed Tokens may utilize blockchain and smart contracts (for example, to facilitate payments). However, because they are primarily related to off-chain operations rather than network ownership, companies can unilaterally control their issuance, utility, and value. Similar to "Arcade Tokens" (described below), Company-Backed Tokens typically have their own embedded utility. But unlike "Arcade Tokens," Company-Backed Tokens have speculative characteristics.

Given these characteristics—although Company-Backed Tokens do not confer explicit rights, ownership, or interests to holders like traditional securities—they have trust dependencies similar to securities: their value essentially depends on a system controlled by individuals, companies, or management teams. Therefore, while Company-Backed Tokens themselves are not securities, their trading may be subject to U.S. securities laws when such tokens attract investment.

Company-Backed Tokens may become a legitimate category. However, they have historically been used in the U.S. primarily to illegally circumvent securities laws—attracting investment in applications, products, or services controlled by the company, potentially serving as substitutes for equity or profit interests in the company. Examples of Company-Backed Tokens include FTT, which serves as a profit interest in the FTX exchange, or hypothetically, a cloud service provider issuing tokens that allow holders to access cloud services and receive a portion of on-chain revenue from such services. Additionally, BNB is also a typical example of a Company-Backed Token that evolved into a Network Token with the launch of Binance Smart Chain. Company-Backed Tokens are sometimes referred to as "startup tokens," or given their link to off-chain applications, also as "application tokens."

With that said, what is the specific distinction between Network Tokens and Company-Backed Tokens?

Distinguishing Network Tokens from Company-Backed Tokens

Distinguishing between Network Tokens and Company-Backed Tokens is not easy, as both types of tokens may have utility and derive some value from the on-chain functionality of the blockchain and the off-chain operations of the company. However, it is necessary to differentiate them: Network Tokens and Company-Backed Tokens pose distinctly different risks to holders and should be treated differently under applicable laws. So, where is the line drawn?

The only key distinguishing feature of Network Tokens from Company-Backed Tokens is that the value of Network Tokens primarily derives from the blockchain or smart contract protocol. This feature is important because these systems can operate autonomously and in a decentralized manner, without human intervention or control. Because of this, blockchain-based networks can be truly open: the network effects of the system are captured on-chain and belong to token holders, and these network effects can, in principle, be accessed and expanded by anyone.

In contrast, the value of Company-Backed Tokens primarily derives from off-chain systems or sources that cannot operate autonomously—that is, centralized systems that require human intervention and control. This association is often evident, such as when the token price is tied to the profits of off-chain applications, products, or services, or when the token has utility within these systems. But it can also be implicit—for example, a token with no actual utility but leveraging a company brand may imply that the company will assign value to it.

In either case, if a token has an inherent association with a system that cannot operate autonomously, and its value primarily (or expectedly) derives from that system, then it is a Company-Backed Token. Due to the lack of autonomy, any related network (even if seemingly public) is, in fact, closed, much like a Web2 social network controlled by a single company, meaning the network effects of the token ultimately belong to the company controlling the system, not the users.

The difference in openness of network design (closed vs. open) has real economic and regulatory consequences.

Network Tokens are associated with uncontrolled open networks, making them more akin to commodities: their operation means that no party can unilaterally influence or construct risks associated with the token. This elimination of trust dependency distinguishes Network Tokens from securities. If the network directs value to the token through its functionality (such as programmatic buybacks and burns), it further reinforces the de-risking characteristic.

Company-Backed Tokens, on the other hand, exhibit trust dependencies similar to securities: if the value of the token derives from a closed network controlled by a single entity, that entity can unilaterally alter the expected value of the token. For example, the controlling entity can arbitrarily change the token's utility, issue more tokens, or even shut down the entire system. This indicates that when people invest in Company-Backed Tokens, securities law should apply.

Two typical cases can further clarify this distinction:

ETH is a typical Network Token. It enables holders to transact on the Ethereum network and provides holders with economic rights to the network. The network operates in a decentralized and autonomous manner (without control by individuals or management teams). Therefore, the U.S. SEC has clearly determined that securities laws do not apply to ETH.

FTT, on the other hand, is a typical Company-Backed Token. Its value entirely depends on the continued operation of the FTX exchange, which is a centralized exchange operated and controlled by a company. FTX extracts a portion of the exchange's profits to buy back FTT, thereby driving its economic value. Therefore, FTT is essentially a profit interest in FTX—its utility and value are controlled by FTX—thus it should be subject to securities laws.

However, tokens that fall between these two extreme cases can become complex. But determining whether a token is a Network Token or a Company-Backed Token can usually be concluded by answering the following three questions:

Is the network design of the system open?

Do the network effects of the system benefit the protocol and token holders?

Can the system enable the protocol and token holders to independently derive value?

If the answers to the above are all "yes," then theoretically, even if the initial development team withdraws, the system can continue to operate (even if functionality is limited). This is crucial because it means the system can operate without being controlled.

Other examples also help illustrate these concepts, such as most tokens associated with decentralized exchange (DEX) protocols, which are Network Tokens, even though the initial development team typically operates the front-end website and off-chain routing software. The reasons are:

DEX protocols are usually open networks, allowing any developer (not just the initial team) to build front-end websites or routing tools on top of the protocol.

Key functions like liquidity in DEX are controlled by the protocol itself, not the development team.

The embedded economic mechanisms within the protocol (such as "fee switches") allow value to flow independently to token holders, meaning the system can sustain itself even if the initial team stops operating.

Taking games as another example, even if most Web3 games do not run entirely on-chain (relying on off-chain services like servers), as long as core assets (items, characters, etc.) are issued on-chain and not under unilateral control, the system can still be considered an open network. If the protocol designs economic mechanisms that direct value to the token (for example, through on-chain transaction fee distribution), then that token belongs to the category of Network Tokens.

In contrast, imagine what would happen if Apple launched an App Store token?

Users holding the token could enjoy discounts in the App Store, use it to pay for app fees, and the App Store would distribute profits to token holders through smart contracts. However, despite the use of blockchain technology, the value of its token would still entirely depend on a closed system controlled by Apple (the App Store), and the use of blockchain would not allow third parties to leverage Apple's network effects and build competitive app stores within its system. Furthermore, the value would come from proprietary off-chain products and services controlled by Apple (the App Store); even with on-chain programmatic economic mechanisms, once Apple shuts down its store, the token's value would drop to zero. Therefore, the risk profile of such tokens is much closer to stocks, distinctly different from Network Tokens, and may be subject to securities laws.

Security Tokens

Security Tokens represent a digital form of securities, which can be traditional forms (such as company stocks or corporate bonds) or have special characteristics, such as providing profit interests in limited liability companies, shares of future income from athletes, or even securitized rights to future litigation settlement payments.

Securities typically confer certain rights, ownership, or interests to holders, and their issuers usually have unilateral power to influence or construct asset risks. As the U.S. SEC is expected to modernize securities laws to allow on-chain trading, the number and types of securities being tokenized may increase, potentially enhancing the efficiency and liquidity of the securities market. However, even as categories continue to grow, digital securities will still be subject to U.S. securities laws.

Security Tokens have been used to raise funds for commercial enterprises. Examples of Security Tokens include Etherfuse Stablebonds and Aspen Coin, the latter representing partial ownership interests in The St. Regis Aspen Resort.

Arcade Tokens

"Arcade Tokens" can specifically refer to "functional tokens within a closed environment," providing utility within the system and not intended for investment purposes. Such tokens are often used as currency in the digital economy, such as digital gold in games, loyalty points in membership programs, or points redeemable for digital products and services.

Importantly, Arcade Tokens differ from Security Tokens, Network Tokens, and Company-Backed Tokens because they are specifically designed to prevent speculation. For example, these tokens may have no supply cap (meaning an unlimited number can be minted) and/or limited transferability; if unused, they may expire or depreciate, or they may only have monetary value and utility within the system that issues them. Crucially, they do not provide, promise, or imply financial returns. Given that they are not suitable as investment products, Arcade Tokens are typically not subject to U.S. securities laws.

For this reason, Arcade Tokens are best used as currency in the digital economy, where the issuer gains economic benefits by controlling the monetary policy of that digital economy (acting as a central bank) and maintaining stable token value, rather than profiting from token value appreciation. Examples include FLY, which is a loyalty and payment token for the Blackbird restaurant network, and Pocketful of Quarters, which is an in-game asset. They exemplify the concept of Arcade Tokens. Arcade Tokens are sometimes also referred to as "utility tokens," "loyalty tokens," or "points."

Collectible Tokens

The value, utility, or significance of Collectible Tokens derives from the record of ownership of tangible or intangible goods. For example, collectible tokens can be digital representations or proxies of artworks, music works, or literary works; tickets or memorabilia from events; memberships in clubs or communities; or assets in games or the metaverse, such as digital swords or plots of metaverse land.

These tokens are typically non-fungible and often have utility. For example, collectible tokens can serve as event permits or tickets; they can be used in video games (like representing a sword); or they can provide ownership related to intellectual property. Since collectible tokens are usually associated with finished products or goods and do not rely on third-party efforts, they are generally not subject to U.S. securities laws.

Collectible Tokens are best suited for conveying ownership of tangible or intangible goods. Many (though not all) "NFT" products fall into this category. Examples include NFTs that convey ownership of digital art or other media; profile pictures (or "pfps") like CryptoPunks and Bored Apes, as well as other virtual fashion and branded goods; game items; and account records or identifiers (such as ENS domains).

Some collectible tokens are directly associated with physical products, either providing a digital extension of the experience of physical products, such as Pudgy Penguins toys and Generative Goods trading cards; or providing a digital representation of physical goods for easier tracking and/or exchange, such as NFT event tickets and BAXUS's wine NFTs.

Asset-Backed Tokens

The value of Asset-Backed Tokens derives from claims or economic risks associated with one or more underlying assets. These underlying assets may include real-world assets (such as commodities, fiat currencies, or securities) or digital assets (such as cryptocurrencies or liquidity pool rights).

Asset-Backed Tokens can be fully or partially collateralized and can serve different purposes: acting as a store of value, hedging tool, or on-chain financial primitives. Unlike collectible tokens that derive value from ownership of unique items (like digital artworks, in-game items, or event tickets), Asset-Backed Tokens function more like financial instruments, deriving value from their collateral, price peg mechanisms, or redemption rights. However, the regulatory treatment of Asset-Backed Tokens depends on their structure and use. Some tokens, such as fiat-backed stablecoins, are typically not subject to U.S. securities laws. Other tokens, such as certain derivative tokens, may be subject to securities or commodities regulation if they represent investment contracts or similar futures-like instruments.

Asset-Backed Tokens have many use cases, including:

Stablecoins: pegged to currencies or assets;

Derivative Tokens: providing synthetic exposure to underlying assets or financial positions;

Liquidity Provider (LP) Tokens: representing claims on pooled assets in decentralized finance (DeFi) protocols;

Deposit Receipt Tokens: representing staked or custodial assets.

Common examples include USDC (a fiat-backed stablecoin), Compound's C Tokens (an LP token), Lido's stETH (a liquid staking token), and OPYN's Squeeth (a derivative token tracking ETH prices).

Memecoin

Memecoins are tokens that lack intrinsic utility or value, often associated with internet memes or community-driven movements, and have no fundamental connection to a network, company, or application.

The price of Memecoins is entirely driven by speculation and related market forces, making them highly susceptible to manipulation. Their main characteristics are a lack of intrinsic purpose (if they have a purpose, they are no longer Memecoins), a lack of utility, and the resulting zero-sum nature and volatility. Memecoins are typically not subject to U.S. securities laws, but they are still subject to anti-fraud and market manipulation laws.

The most typical examples include PEPE, SHIB, and TRUMP.

Among the seven types of tokens mentioned above, not all tokens fit perfectly into these categories—developers regularly iterate and experiment with new models. For example, if social and reputation tokens are non-investable, they may resemble "Arcade Tokens" more closely, and if they are controlled by centralized issuers, they may resemble Company-Backed Tokens more closely. As token characteristics change or new functionalities are added, tokens can also evolve from one category to another, making classification challenging.

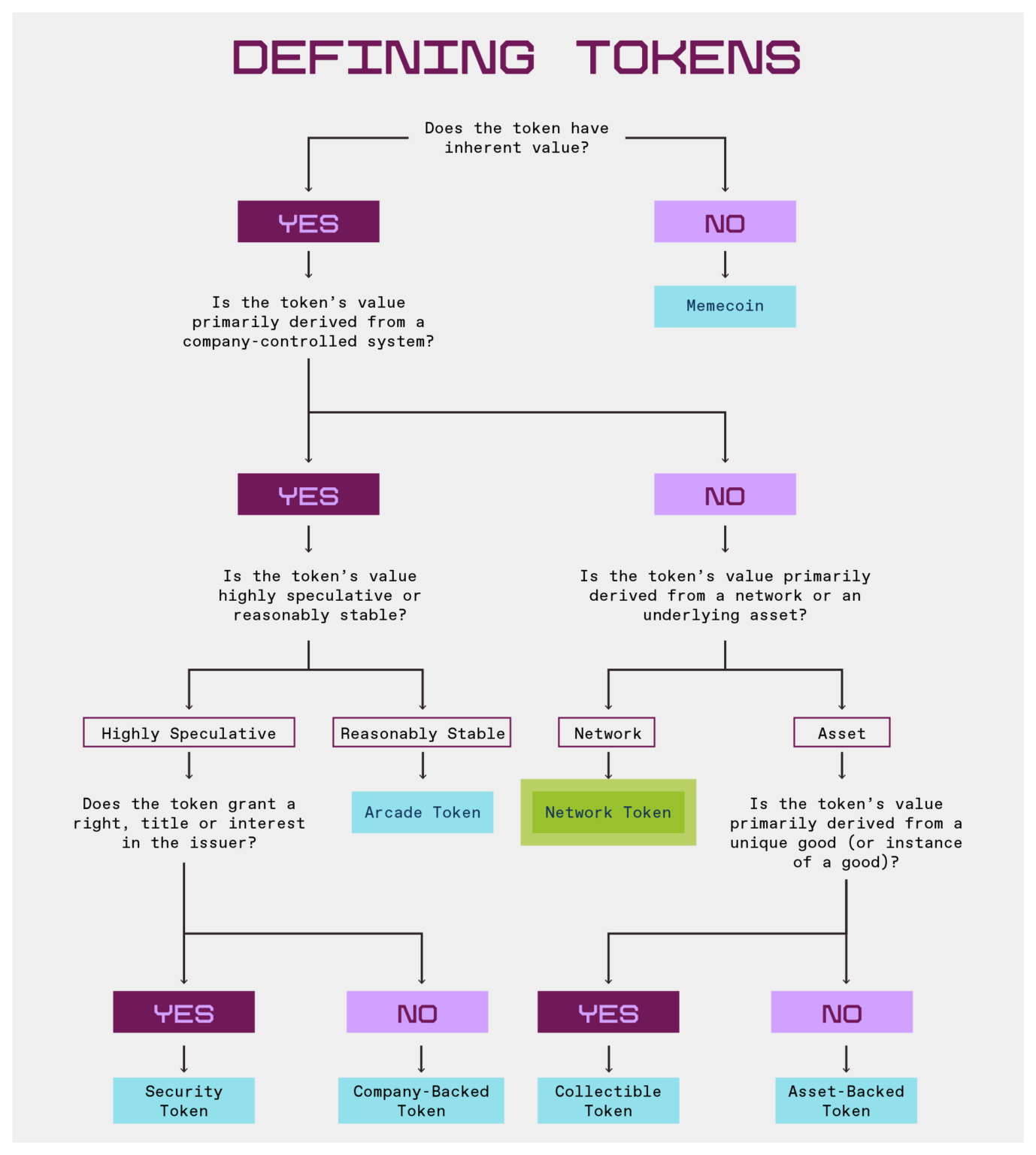

But the decisive characteristic for delineating these categories is the expected source of value accumulation, and the flowchart below helps illustrate this point:

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。