Vitalik does not particularly care about the price of ETH.

Compiled by: Golden Finance

When ETH keeps falling and many users shout "Fix your eth" under Vitalik's tweets, people are curious about what Vitalik, as the founder of Ethereum, is thinking.

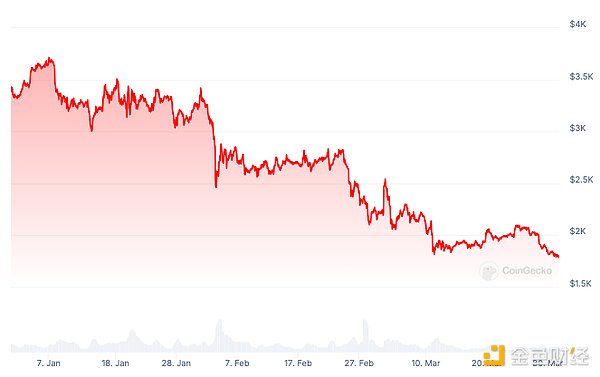

ETH falls below $1800 Source: Coingecko

On March 29, 2025, Vitalik published two blog posts that reveal his current thoughts. Clearly, Vitalik does not particularly care about the price of ETH.

Here are the two recent blog posts by Vitalik:

First, the Year Ring Model of Culture and Politics

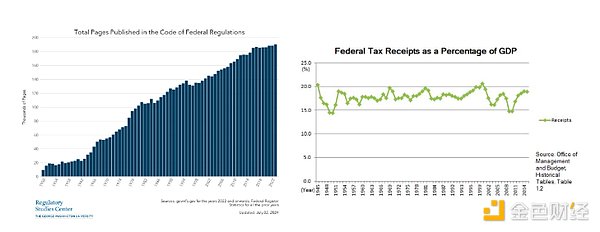

One thing that often confuses me as I grew up is that people frequently claim we live in a "deeply neoliberal society" that highly values "deregulation." I find it puzzling because while I see quite a few people advocating for neoliberalism and deregulation, the actual state of government regulation is very different from any regulation that could reflect these values. The total number of federal regulations has been continuously increasing. KYC, copyright, airport security checks, and various other rules are tightening. Since World War II, the percentage of federal tax revenue in GDP in the United States has remained roughly constant.

If you told someone in 2020 that five years later, the U.S. or China would lead in open-source AI, while the other would lead in closed-source AI, and asked them which would lead where, they might stare at you as if you were asking a tricky question. The U.S. is a country that values openness, while China values closure and control; American technology is generally more inclined towards open-source than Chinese technology—this is obvious! However, they would be completely wrong.

What is going on? In this article, I will propose a simple explanation, which I call the year ring model of politics and culture:

The model is as follows:

- How a culture treats new things is a product of the attitudes and incentives that are popular in that culture at a specific time.

- How a culture treats old things is mainly influenced by status quo bias.

Each period adds a new ring to the tree, and as the new ring forms, people's attitudes towards new things also take shape. However, soon these boundaries become fixed and hard to change, and new rings begin to grow, influencing people's attitudes towards the next wave of topics.

We can analyze the above situation and others from the following perspectives:

- There is indeed a trend towards deregulation in the U.S., but this trend was most evident in the 1990s (if you look closely, you can actually see this in the charts!). By the 21st century, the tone has shifted towards increased regulation and control. However, if you look at the specific things that "matured" in the 1990s (like the internet), you will find that they eventually became regulated, and the basis for that regulation was the principles that dominated the 1990s, which allowed the U.S. (and much of the world due to imitation) to enjoy decades of relative internet freedom.

- Taxation is constrained by budgetary needs, which are primarily determined by the demand for healthcare and welfare programs. The "red line" in this regard was set over 50 years ago.

- Both law and culture view all moderately dangerous activities involving modern technology as more suspicious than dangerous activities like mountaineering, which have a very high mortality rate. This can be explained by the fact that dangerous mountaineering activities are things people have been doing for centuries, and when the general risk tolerance is much higher, people's attitudes become firm.

- Social media matured in the 2010s, and culture and politics viewed it as part of the internet on one hand, while on the other hand, they saw it as a unique entity. Therefore, the restrictive attitudes towards social media typically do not carry over from the early internet—despite the general growth of internet authoritarianism, we have not seen particularly strong attempts to crack down on unauthorized file sharing.

- Artificial intelligence matured in the 2020s, with the U.S. as the leading power and China closely following. Therefore, adopting a "complementary commodification" strategy in AI aligns with China's interests. This intersects with the general support for open-source among many developers. The result is that the environment for open-source AI is very real but also quite specific to AI; older technological fields remain closed, like walled gardens.

More generally, the implication here is that it is difficult to change a culture's way of treating things that already exist and how it treats things that have already solidified in attitude. It is easier to invent new behavioral patterns to transcend old ones and strive to maximize our chances of obtaining good norms. This can be achieved in various ways: developing new technologies is one, and using (physical or digital) communities on the internet to experiment with new social norms is another. For me, this is also one of the attractions of the crypto space: it provides an independent technological and cultural foundation to do new things without being overly burdened by existing status quo biases. We can revitalize the forest by planting and nurturing new trees instead of planting the same old trees.

Second, We Should Talk Less About Public Goods Funding and More About Open Source Funding

One topic I have long been concerned about is how to fund public goods. If a project provides value to a hundred million people (and there is no fine way to select who benefits and who does not), but everyone only receives a small portion of the benefits, then it is likely that no one will feel that funding this project aligns with their interests, even if the project is overall very valuable. In economics, the term "public goods" has a century-long history. In digital ecosystems, especially decentralized digital ecosystems, public goods are extremely important: in fact, there is ample reason to suggest that the average goods people might want to produce are public goods. Open-source software, academic research on cryptography and blockchain protocols, publicly available educational resources, and more are all public goods.

However, the term "public goods" faces significant challenges. In particular:

The term "public goods" is often used in public discourse to refer to "government-produced products," even if they are not public goods in the economic sense. This can create confusion, as it leads to the perception that whether a project is a public good does not depend on the project itself and its attributes, but rather on who is building it and what their stated intentions are.

There is a general perception that public goods funding lacks rigor, operates based on social expectation biases (sounds good rather than actually good), and favors insiders who can play social games.

For me, these two issues are related: the term "public goods" is easily influenced by social games, largely because the definition of "public goods" is easily expanded.

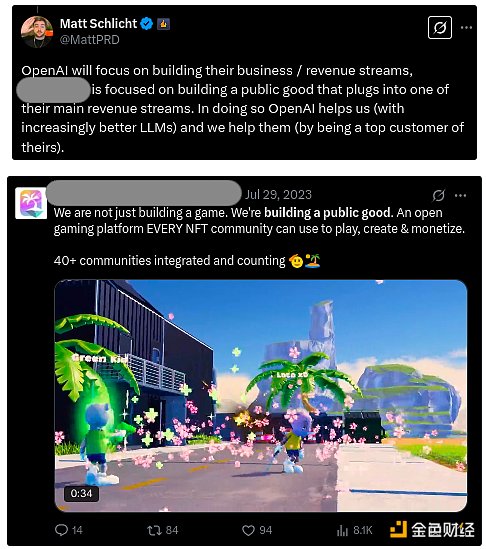

Let's see what happens when we search for the phrase "building public interest" on Twitter. I just searched it, and here are some of the first results:

You can keep scrolling and find many projects using "We are building public goods" to describe themselves.

This is not meant to criticize individual projects; I am not very familiar with the two projects mentioned above, and they could both be great projects. However, both examples are commercial projects with their own tokens. There is nothing wrong with being a commercial project, and launching your own token is often not wrong either. However, when it is so easily diluted to this point, the term "public goods" now seems to just refer to a "project."

Open Source

As an alternative to "public goods," let’s think about the term "open source." If you consider some obvious core examples of digital public goods, you will find that they are all open source:

- Academic blockchain and cryptographic protocol research

- Documentation, tutorials…

- Open-source software (e.g., Ethereum clients, software libraries…)

On the other hand, open-source projects seem to default to being public goods. You can certainly cite counterexamples: if I write software highly tailored to my personal workflow and put it on GitHub, then most of the value created by that project may still belong to me personally. However, the act of open-sourcing (as opposed to keeping it secret) is certainly a public good, with benefits being very dispersed.

One real advantage of the term "open source" is that it has a clear and widely recognized definition. The FSF's definition of free software and the OSI's definition of open source have existed for decades and have natural ways to extend these definitions to areas beyond software (such as writing, research). In the crypto space, the inherent state and multi-party nature of applications, along with the new centralization vulnerabilities and control vectors these factors imply, do mean we need to slightly expand that definition: open standards, internal attack testing, and walkaway testing introduced in this article can be valuable additions to the FSF + OSI definitions.

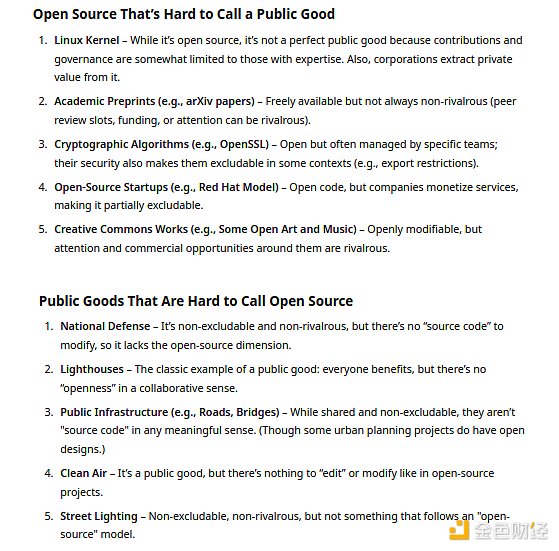

So what is the difference between "open source" and "public goods"? Well, we can first let the robots give a few examples:

I personally completely disagree with the assertion that the first category of examples is not public goods. A project having a high barrier to contribution does not prevent it from being a public good, nor do the companies benefiting from that project. Furthermore, a project can absolutely be a public good while the things surrounding it are private goods.

The second category is more interesting. First, we should note that all five examples are in physical space, not digital space. Therefore, if we want to focus on digital public goods, there is no reason to oppose focusing solely on "open source." But what if we do want to cover physical goods? Even the crypto space has its own enthusiasm for better managing physical things rather than just digital ones; in a sense, that is the whole point of network states.

Open Source and Local Physical Public Goods

Here, we can make an observation: while providing these things locally is an "infrastructure building" issue and can be done in either an open-source or closed-source manner, the most effective way to provide these things globally often ultimately involves… true open source. Clean air is the most obvious example: a significant amount of research and development has been conducted, much of it open source, to help people around the world enjoy cleaner air. Open source can facilitate the easier global deployment of any type of public infrastructure. The question of how to effectively provide physical infrastructure locally remains important—but this question is equally applicable to democratically managed communities and companies.

Defense is an interesting case. Here, I want to make the following argument: if you establish a project that you are unwilling to open source for defense reasons, then it is very likely that, while it may serve the public interest locally, it may not serve the public interest globally. Weapons innovation is the most obvious example. Sometimes, one side in a war has stronger moral reasons, making it reasonable to assist them in offensive actions, but on average, developing technology to enhance military capabilities does not improve the world. Exceptions (defense projects that people want to open source) may actually relate to "defensive" capabilities; one example could be decentralized agriculture, power, and internet infrastructure that can help people maintain food security, normal operations, and connectivity in challenging environments.

Therefore, shifting the focus from "public goods" to "open source" seems to be the best choice here. Open source should not mean "as long as it is open source, building anything is equally noble"; it should be about building and open sourcing what is most valuable to humanity. However, distinguishing which projects are worth supporting and which are not is already a well-known primary task of public goods funding mechanisms.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。