Closing positions and liquidation are the "fate" that every exchange and trader will eventually face. If opening a position is the beginning of a relationship, filled with emotions, beliefs, and fantasies, then closing a position is the end of that story, whether willingly or with reluctance.

In fact, forced liquidation is a "thankless" task for exchanges; it not only offends users but can also lead to significant losses for the exchange itself if not handled carefully, and no one will pity them when that happens. Therefore, mastering the art of balancing risk and reward is true skill.

To add, don't be misled by the wealth creation effect—liquidation mechanisms are the conscience and responsibility of an exchange.

Today, we will only discuss structure and algorithms. What is the true logic behind forced liquidation? How does the liquidation model protect the overall safety of the market?

Leverage disclaimer: If you think I am wrong, then you are right.

Entertainment disclaimer: Don't focus too much on the numbers; pay more attention to the logic. Just get a general idea and enjoy.

Part One: Core Risk Management Framework of Perpetual Contracts

As a complex financial derivative, perpetual contracts allow traders to amplify capital effects through leverage, providing opportunities for returns far exceeding the initial capital. However, this potential for high returns comes with equal or even greater risks. Leverage not only amplifies potential profits but also potential losses, making risk management an indispensable core aspect of perpetual contract trading.

The core of this system lies in effectively controlling and mitigating the systemic risks arising from high-leverage trading. It is not a single mechanism but a "terraced" risk control process composed of multiple interrelated, progressively triggered defense layers. This process aims to limit losses caused by individual account liquidations within a controllable range, preventing them from spreading and impacting the entire trading ecosystem.

How to transform the force of a waterfall into the gentleness of a stream—loose yet not leaking, strong yet soft.

Three Pillars of Risk Mitigation

The risk management framework of the exchange primarily relies on three pillars, which together form a comprehensive defense network from individual to system, from routine to extreme:

Forced Liquidation: This is the first and most commonly used line of defense in risk management. When market prices move against a trader's position, causing their margin balance to be insufficient to maintain the position, the exchange's risk engine automatically intervenes to forcibly close the losing position.

Insurance Fund: This is the second line of defense, acting as a buffer against systemic risks. During severe market fluctuations, the execution price of forced liquidation may be worse than the trader's bankruptcy price (the price at which losses exhaust all margin), and the additional losses (known as "negative balance losses") will be compensated by the insurance fund.

Auto-Deleveraging (ADL): This is the final and rarely triggered line of defense. The ADL mechanism is activated only in extreme market conditions (i.e., "black swan" events) that lead to large-scale forced liquidations exhausting the insurance fund. It compensates for negative balance losses that the insurance fund cannot cover by forcibly reducing the positions with the highest profits and leverage in the market, ensuring the exchange's solvency and the overall stability of the market.

These three pillars together form a logically coherent risk control chain. The design philosophy of the entire system can be understood as an economic "social contract," which clarifies the principle of risk responsibility distribution in the high-risk environment of leveraged trading.

Trader bears risk → Insurance fund → Auto-Deleveraging mechanism (ADL)

First, the risk is borne by the individual trader, whose responsibility is to ensure that their account has sufficient margin. When individual responsibility cannot be fulfilled, the risk is transferred to a collective buffer pool (pre-funded through liquidation fees, etc.)—the insurance fund. Only in extreme situations where this collective buffer pool also cannot withstand the shock does the risk transfer directly to the most profitable participants in the market through auto-deleveraging. This layered mechanism is designed to isolate and absorb risks to the greatest extent, maintaining the health and stability of the entire trading ecosystem.

Part Two: The Basics of Risk: Margin and Leverage

In perpetual contract trading, margin and leverage are the two fundamental elements that determine a trader's level of risk exposure and potential profit and loss. A deep understanding of these concepts and their interactions is a prerequisite for effective risk management and avoiding forced liquidation.

Initial Margin and Maintenance Margin

Margin is the collateral that traders must deposit and lock in to open and maintain leveraged positions. It is divided into two key levels:

Initial Margin: This is the minimum amount of collateral required to open a leveraged position. It serves as the "ticket" for traders to enter leveraged trading, typically calculated as the nominal value of the position divided by the leverage ratio. For example, to open a position worth 10,000 USDT with 10x leverage, a trader needs to invest 1,000 USDT as the initial margin.

Maintenance Margin: This is the minimum amount of collateral required to maintain an open position. It is a dynamically changing threshold, lower than the initial margin. When market prices move unfavorably, causing the trader's margin balance (initial margin plus or minus unrealized profit and loss) to fall to the maintenance margin level, the forced liquidation process will be triggered.

Maintenance Margin Ratio (MMR): Refers to the minimum collateral ratio.

Margin Model Analysis: Comparative Analysis

Exchanges typically offer various margin models to meet the risk management needs of different traders. The main types include:

Isolated Margin: In this model, traders allocate a specific amount of margin for each position. The risk of that position is independent; if forced liquidation occurs, the maximum loss the trader bears is limited to the margin allocated for that position, without affecting other funds or positions in the account.

Cross Margin: In this model, all available balances in the trader's futures account are considered shared margin for all positions. This means that losses from one position can be offset by other available funds or unrealized profits from other profitable positions, thereby reducing the risk of forced liquidation for a single position. However, the downside is that once forced liquidation is triggered, the trader may lose all funds in the account, not just the margin for a single position.

Portfolio Margin: This is a more complex margin calculation model designed for experienced institutions or professional traders. It assesses margin requirements based on the overall risk of the entire portfolio (including various products such as spot, futures, options, etc.). By identifying and calculating the risk-hedging effects between different positions, the portfolio margin model can significantly reduce margin requirements for well-hedged, diversified portfolios, thereby greatly improving capital efficiency.

Tiered Margin System (Risk Limits)

To prevent significant impacts on market liquidity due to a single trader holding excessively large positions during forced liquidation, exchanges generally implement a tiered margin system, also known as risk limits. The core logic of this system is that the larger the position size, the higher the risk, thus requiring stricter risk control measures.

Specifically, this system divides the nominal value of positions into multiple tiers. As the value of the positions held by traders rises from lower to higher tiers, the platform automatically implements two adjustments:

Lowering the Maximum Available Leverage: The larger the position, the lower the maximum leverage allowed.

Increasing the Maintenance Margin Ratio (MMR): The larger the position, the higher the proportion of margin required to maintain the position relative to its value.

This design effectively prevents traders from using high leverage to establish large positions that could pose systemic threats to market stability. It serves as an embedded risk reduction mechanism, forcing large traders to actively reduce their risk exposure.

The tiered margin system is not merely a risk parameter but a core tool for exchanges to manage market liquidity and prevent "liquidation cascades." A large-scale forced liquidation order (e.g., from a whale account using high leverage) could instantly deplete liquidity at multiple price levels on the order book, leading to a sharp price drop with a "long lower shadow." This sudden price drop could trigger forced liquidation lines for other positions that were originally safe, creating a domino effect. (For exchanges, this means negative balance risk.)

By imposing lower leverage and higher maintenance margin requirements on large positions, exchanges significantly increase the difficulty for any single entity to build a vulnerable large position capable of triggering such chain reactions. Higher margin requirements act as a larger buffer, capable of absorbing more severe price fluctuations, thus protecting the entire market ecosystem from systemic risks posed by concentrated positions.

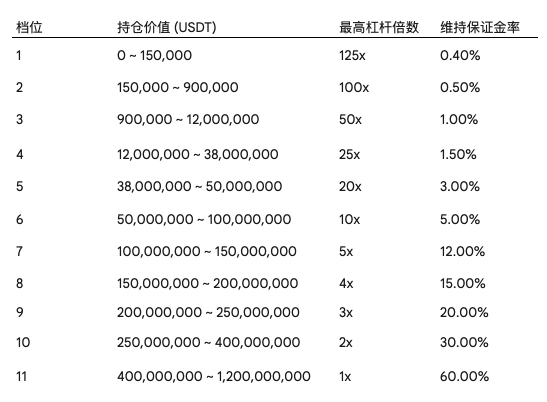

Taking Bitget's tiered margin system for the BTCUSDT perpetual contract as an example, it clearly demonstrates the practical application of this risk management mechanism:

Table 1: Example of Tiered Margin for BTCUSDT Perpetual Contract (Source: Bitget)

This table intuitively reveals the inverse relationship between risk and leverage—the margin rate requirements increase linearly with position size. When the value of a trader's BTCUSDT position exceeds 150,000 USDT, their maximum available leverage will drop from 125x to 100x, while the maintenance margin rate will increase from 0.40% to 0.50%.

Part Three: Forced Liquidation Triggers: Understanding Key Price Indicators

To execute forced liquidation accurately and fairly, the exchange's risk engine does not directly use the rapidly changing transaction prices in the market but relies on a specially designed system of price indicators.

Mark Price vs. Last Transaction Price

In the perpetual contract trading interface, traders typically see two main prices:

Last Price: This refers to the price of the most recent transaction on the exchange's order book. It directly reflects current market buying and selling behavior and is easily influenced by large individual trades or short-term market sentiment.

Mark Price: This is a price specifically calculated by the exchange to trigger forced liquidation, aiming to reflect the contract's "fair value" or "true value." Unlike the last price, the calculation of the mark price incorporates multiple data sources, with the core purpose of smoothing short-term price fluctuations to prevent unnecessary and unfair forced liquidations caused by insufficient market liquidity, price manipulation, or sudden "spike" events. (Currently, mark price is used as the basis for profit and loss.)

The calculation method for mark price is generally similar across exchanges and typically includes the following core components:

Index Price: This is a composite price calculated by taking a weighted average of asset prices from multiple major spot exchanges worldwide.

Funding Basis: To anchor the perpetual contract price close to the spot price, there exists a price difference, known as the basis, between the contract price and the index price.

Through this comprehensive calculation method, the mark price can more stably and reliably reflect the intrinsic value of the asset, becoming the sole basis for triggering forced liquidation. (For detailed mark price information, see:

https://x.com/agintender/status/1944743752054227430,

https://x.com/agintender/status/1937104613540593742

Liquidation Price and Bankruptcy Price

Under the mark price system, there are two price thresholds that are crucial to a trader's fate:

Liquidation Price: This is a specific value of the mark price. When the mark price in the market reaches or crosses this price point, the trader's position will trigger the forced liquidation process. This price point corresponds to the trader's margin balance falling to the maintenance margin requirement level. (The liquidation price is the trigger condition for liquidation.)

Bankruptcy Price: This is another value of the mark price, representing the price point at which the trader's initial margin has been completely lost. In other words, when the mark price reaches the bankruptcy price, the trader's margin balance will be zero. (The bankruptcy price is the price used for liquidation.)

Note that the triggering of the liquidation price always occurs before the bankruptcy price.

The price range between the liquidation price and the bankruptcy price constitutes the "operational buffer zone" of the exchange's risk engine. The efficiency of the liquidation system is tested within this narrow range.

In simple terms, the higher the leverage, the lower the initial margin rate, and the narrower this buffer zone becomes. For example, a position with 100x leverage has an initial margin rate of only 1%, while the maintenance margin rate may be 0.5%. This means that from opening the position to triggering liquidation, the trader has only 0.5% of price fluctuation space.

For instance, if you open a long position with 100x leverage, intuitively, it seems that only a 1% price drop would lead to "bankruptcy." However, because the margin rate is 0.5%, a 0.5% price drop will trigger liquidation, and the position will be liquidated at the bankruptcy price after a 1% drop.

This direct causal relationship between leverage and vulnerability is the fundamental reason why high-leverage trading carries extremely high risks, contrary to intuition.

If the liquidation engine can efficiently close positions within this range and the execution price is better than the bankruptcy price, the remaining "profit" will be injected into the insurance fund, and users will not "owe" the exchange;

Conversely, if extreme market fluctuations or liquidity exhaustion lead to the liquidation price being worse than the bankruptcy price, the resulting negative balance losses will need to be covered by the insurance fund, or even require users to compensate for this loss.

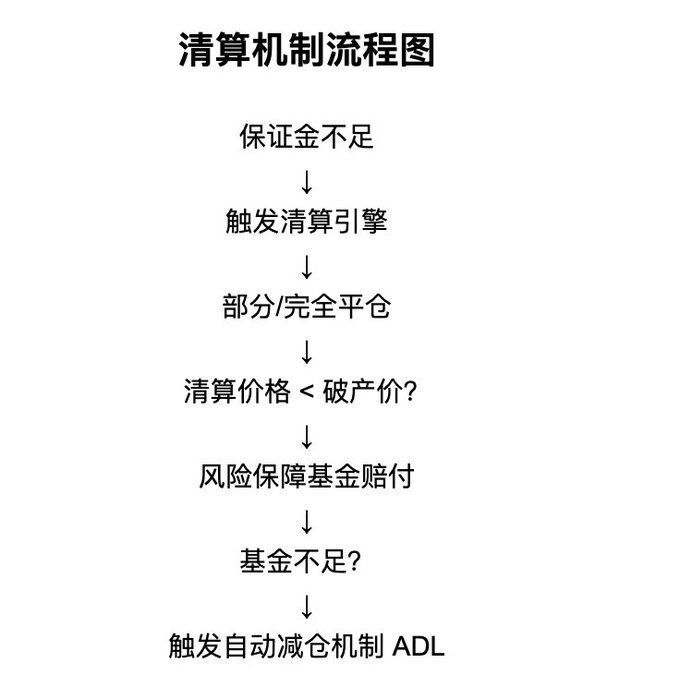

Part Four: Forced Liquidation Process: Step-by-Step Explanation

When a trader's position risk reaches a critical point, i.e., when the mark price touches the liquidation price, the exchange's risk engine will immediately initiate a standardized, fully automated forced liquidation process. This process aims to orderly close risk positions while minimizing market impact.

To add, don't be misled by the wealth creation effect—the liquidation mechanism is the conscience and responsibility of an exchange.

Triggering Liquidation

The starting point of the process is the fulfillment of the liquidation condition: the mark price reaches or crosses the pre-calculated liquidation price. At the system level, this is equivalent to the maintenance margin rate (MMR) of the position reaching 100%. Once triggered, the trader will lose control of the position, and all subsequent operations will be taken over by the risk engine.

After the liquidation condition is triggered, the user's position is taken over by the liquidation engine and settled internally at the "bankruptcy price." (The bankruptcy price is worse than the liquidation price.) The relationship between these two prices reveals the core logic of the forced liquidation mechanism: the exchange's risk engine always initiates the liquidation process when the liquidation price is triggered, striving to complete the position closure before reaching the bankruptcy price.

Transforming the Waterfall of Liquidation into a Gentle Stream

Once the risk engine takes over, it generally executes the following operations in a preset order (which may vary between exchanges):

Cancel Unfilled Orders: The first step of the process is to immediately cancel all unfilled orders related to the risk position. In isolated margin mode, the system will cancel all opening or adding orders for that trading pair; in cross margin mode, the system may cancel all orders in the account that could increase risk exposure.

Partial Liquidation or Tiered Liquidation: For traders holding larger positions at higher margin tiers, the risk engine will not push the entire position to the market all at once. Instead, it will adopt a more cautious "tiered liquidation" or "partial liquidation" strategy. The system will calculate how much of the position needs to be liquidated to bring the account's maintenance margin rate (MMR) back below the safe level of 100%, and then issue liquidation instructions only for that portion of the position. This gradual approach aims to break down large liquidation orders into multiple smaller orders, significantly reducing the immediate impact on market prices and avoiding triggering a chain reaction. (Some may think that partial liquidation is an operation of ADL, but that is not the case.)

Complete Liquidation: If, after the partial liquidation operation, the account's MMR remains above or equal to 100%, or if the position itself is already at the lowest margin tier (requiring no tiered processing), the risk engine will take over the remaining entire position. Subsequently, the system will liquidate these positions on the order book at the best available price using market orders until the position is fully closed.

The tiered liquidation mechanism is an important reflection of the maturity of risk management in modern cryptocurrency derivatives exchanges. Early platforms often adopted an "all or nothing" liquidation model, which, while easy to implement, carried significant risks. A sudden market price liquidation of a large position can easily cause severe price "spikes," triggering other traders' liquidation lines and resulting in destructive "liquidation cascades."

Another key point of forced liquidation is where the position is liquidated. Is it liquidated in the market? Internally absorbed? Or liquidated within the account? Or in the insurance fund? Due to space constraints, this article will not elaborate on this; I will write a separate analysis when I have the opportunity. (For those who say AI creates content, think about how to start writing?! ?)

Liquidation Fees

When a position is forcibly liquidated, the trader not only bears the losses of the position itself but also typically has to pay an additional liquidation fee (or settlement fee). This fee rate is usually higher than ordinary trading fees.

The main purposes of establishing liquidation fees are twofold:

Incentivize Proactive Risk Management: The higher cost of fees aims to encourage traders to actively manage their position risks, such as by setting stop-loss orders or manually closing positions as they approach the liquidation price, rather than passively waiting for the system to enforce liquidation.

Fund the Insurance Fund: Liquidation fees are the primary source of funding for the insurance fund. The exchange injects the collected liquidation fees into this fund pool to address potential negative balance losses in the future, thereby maintaining the healthy operation of the entire risk management system.

Part Five: Safety Net: Insurance Fund and Auto-Deleveraging Mechanism (ADL)

Once the forced liquidation process is initiated, the core challenge faced by the system is to complete the liquidation at a price better than the bankruptcy price before the trader's margin is exhausted. However, this is not always achievable under extreme market conditions. To address the resulting negative balance losses, exchanges have established two crucial system-level safety nets: the insurance fund and the auto-deleveraging mechanism (ADL).

Insurance Fund

Core Purpose: The insurance fund is a pool of funds established and managed by the exchange, fundamentally aimed at compensating for negative balance losses arising from forced liquidations. When the final transaction price of a forcibly liquidated position is worse than its bankruptcy price, it means the trader's losses have exceeded their total margin contribution. At this point, the insurance fund will intervene to fill this loss gap with funds from the pool.

Sources of Funding: The funding for the insurance fund primarily comes from two channels:

Liquidation Fees: The exchange collects additional liquidation fees from all forcibly liquidated positions, which serve as the most stable and primary source of income for the fund pool.

Liquidation Surplus: If a position is forcibly liquidated and the final transaction price is better than its bankruptcy price, the remaining margin after deducting the liquidation fees will also be injected into the insurance fund.

- Transparency and Importance: The size and health of the insurance fund are key indicators of an exchange's risk resilience. Therefore, reputable exchanges typically disclose their insurance fund's wallet addresses and asset balances to the public regularly or in real-time, demonstrating their transparency and solvency.

Mainstream exchanges in the market, such as Binance, OKX, Bybit, and Bitget, have established insurance funds as a strategic decision to instill confidence in the market.

This move reduces the risk of the fund's value significantly shrinking during a market crash (which is precisely when it needs to function the most). Therefore, when traders choose a platform, they should not only focus on trading fees and product features but also examine the size, historical performance, and asset composition of its insurance fund, as these are important reflections of the platform's long-term stability and commitment to user protection.

Auto-Deleveraging Mechanism (ADL) — The Last Line of Defense

Trigger Conditions: The auto-deleveraging (ADL) mechanism is the last line of defense in the exchange's risk management system and is only activated in the most extreme situations. The sole trigger condition is when large-scale, severe market fluctuations occur, causing the total amount of negative balance losses to exceed the entire balance of the insurance fund.

Core Function: The essence of the ADL mechanism is a forced liquidation of counterparties. Once the insurance fund is exhausted, to compensate for system losses, the exchange's risk engine will automatically select traders in the market who hold positions opposite to the bankrupt positions, with the highest profits and leverage, and forcibly liquidate part or all of their profitable positions. These selected profitable positions will be settled at the bankruptcy price of the bankrupt position, and the realized profits will be used to cover the system losses.

The existence of the ADL mechanism ensures that even in the most extreme situations, the exchange itself will not fall into a solvency crisis due to bearing negative balance losses, thus protecting the entire platform's continuity. Although it represents a loss for the selected profitable traders, it avoids the "socialized loss" model of indiscriminately distributing losses to all users, and is considered the lesser of two evils as a final solution.

Note: Due to space constraints, a detailed explanation of the auto-deleveraging mechanism is placed in the appendix, and interested readers can refer to it.

Conclusion: A Comprehensive Consideration of Risk Management and Trader Responsibility

The risk management system of perpetual contracts is a meticulously designed multi-layered defense structure, with the core goal of maintaining market fairness, stability, and continuous operation in a high-leverage trading environment. From individual traders' margin management to the collective buffer of the insurance fund, and finally to the last line of defense in extreme situations—the ADL—this "waterfall terracing" risk control process is interconnected, collectively building a solid barrier against systemic risks.

The logical hierarchy of systemic defense: The entire framework reflects the gradual transfer and resolution of risk from the individual to the collective. Forced liquidation first confines risk at the individual trader level, requiring them to be responsible for their positions. When individual risk spirals out of control and results in negative balance losses, the insurance fund is activated, utilizing the collective funds accumulated from past liquidation events to absorb the shock, thereby protecting other market participants.

Only in the extreme case where both lines of defense are breached will the ADL mechanism intervene, ensuring the overall solvency of the trading platform by liquidating the most profitable traders. The existence of this series of mechanisms is the cornerstone that allows the perpetual contract market to maintain operations amid severe volatility.

Core Responsibility of Traders: Although exchanges provide powerful automated risk management tools, traders must be acutely aware that the ultimate responsibility for risk management lies with themselves. The platform's risk control system is a baseline safeguard, not a part of a profit strategy. Relying on the system's forced liquidation as a "final stop-loss" not only erodes capital due to additional liquidation fees but also exposes traders to potential risks from ADL in extreme market conditions.

Recommendations for Responsible Leverage Trading Practices:

Utilize Risk Management Tools: Before opening any leveraged position, reasonable stop-loss orders should be set in advance. This is the most effective means of actively controlling losses and avoiding hitting the liquidation line.

Choose Leverage Cautiously: Leverage is an amplifier of risk. Traders should select a moderate leverage multiple based on their risk tolerance, trading strategy, and market conditions, avoiding the blind pursuit of nominal gains from high leverage. Understanding the significance and impact of nominal leverage versus actual leverage is crucial.

Understand and Monitor Margin Requirements: It is essential to fully understand the tiered margin system and be aware of the changes in maintenance margin rates at different position sizes. When increasing positions, one should estimate the impact on the liquidation price when moving to a higher tier.

Stay Vigilant and Actively Monitor: Traders should continuously pay attention to the distance between their position's liquidation price and the current mark price. During periods of increased market volatility, they should closely monitor changes in the ADL risk indicator, and once the risk level rises, decisive measures such as reducing leverage or taking partial profits should be taken.

Final Thoughts

Forced liquidation is not a demon, but the cost of maintaining order in the contract market; liquidation is not a punishment, but a necessary mechanism for the system's survival; ADL is not a bias, but a reluctant choice to allow trading to continue.

You can have emotions, but you must understand the rules. Because in this game of trading, what truly counts is not whether you "think it's worth it," but the moment you "can afford the cost."

Perpetual contracts are not "eternally indestructible"; they are merely a redistribution of risk along the timeline.

Know what it is, and also know why it is so.

May we always maintain a sense of reverence for the market.

——————————Appendix Below————————

Appendix: Detailed Explanation of the Auto-Deleveraging (ADL) Mechanism — The Confidence of Exchanges in Remaining Unbeatable

The auto-deleveraging (ADL) mechanism, as the ultimate means of risk management for exchanges, has a complex operational mechanism but is crucial for traders with high leverage and high profits. Understanding its ranking rules, execution processes, and how to mitigate risks is essential knowledge for every mature perpetual contract trader.

ADL Ranking System

When ADL is triggered, the system does not randomly select counterparties for liquidation but follows a strict ranking rule based on risk and profit. All traders holding opposite positions will be placed in a priority queue, with the highest-ranked traders being executed for auto-deleveraging first.

- ADL Ranking Calculation Formula: Although the formula expressions may vary slightly among exchanges, the core logic is highly consistent. The ranking score (ADL Rank) is primarily determined by two variables: profit percentage (PnL Percentage) and effective leverage (Effective Leverage).

For profitable positions: Ranking Score = Profit Percentage × Effective Leverage

For losing positions (although the probability of being selected is extremely low): Ranking Score = Effective Leverage × Profit Percentage

Core components of the formula explained:

Profit Percentage (PnL Percentage): This refers to the unrealized profit and loss amount of the position as a percentage of the position's opening value. The more profit, the larger this value.

Effective Leverage (Effective Leverage): This is the most critical and easily misunderstood part of the entire formula. It is not the leverage multiple chosen by the user when opening a position, but rather reflects the current real risk exposure of the position as a dynamic leverage. Its calculation formula is:

Effective Leverage = (Wallet Balance + Unrealized Profit and Loss) / |Position Nominal Value|

This formula reveals an important phenomenon: when a position's unrealized profit increases, the denominator grows, and its effective leverage decreases. Conversely, when a position approaches liquidation, its unrealized losses cause the denominator to shrink sharply, resulting in a very high effective leverage. Therefore, the ADL system prioritizes those traders who are currently highly profitable and have initially high leverage.

ADL Risk Indicator

To allow traders to intuitively understand their risk of being subject to ADL, trading platforms typically provide a risk indicator on the position interface. This indicator usually consists of five levels (or five small lights), with more lit lights indicating a higher ranking of the position in the ADL queue and a greater risk of being auto-deleveraged. When all five lights are lit, it means the position is at the highest risk level.

ADL Execution Process

Assuming a severe market downturn occurs, leading to a large number of long positions being liquidated, exhausting the insurance fund due to negative balance losses. The ADL system is triggered, and the execution process is as follows:

Identify Counterparties: The system scans all traders holding short positions.

Calculate Rankings: Based on the above ADL ranking formula, calculate the ranking score for each short position and generate a priority queue from highest to lowest.

Execute Deleveraging: The system starts executing deleveraging from the top trader in the queue (the one with the highest ranking score). Assuming the loss to be compensated corresponds to a position of 100 BTC, and the top-ranked trader holds a profitable short position of 20 BTC, the system will forcibly liquidate this 20 BTC position.

Price and Fees: The liquidated position will be settled at the bankruptcy price of the long position that triggered this ADL event. The trader subject to ADL does not need to pay any trading fees.

Loop Execution: If the top-ranked trader's position is insufficient to fully cover the loss (for example, there is still an 80 BTC loss gap), the system will continue to execute deleveraging on the second and third-ranked traders until all negative balance losses are completely covered.

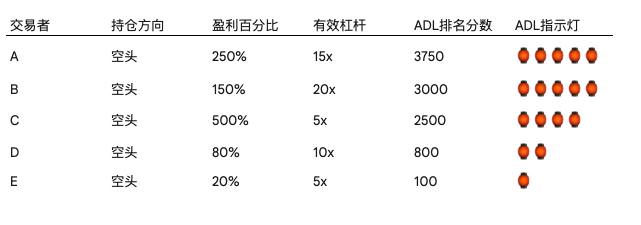

For those reading this, it may be confusing, so here’s an example:

Table 2: Example of ADL Counterparty Ranking Queue

This clearly reveals the core logic of ADL ranking. Trader C has the highest profit percentage (500%), but due to their low effective leverage (5x), their ADL ranking score (2500) is lower than that of traders A (250% * 15x = 3750) and B (150% * 20x = 3000), who have lower profit percentages but higher effective leverage. This intuitively demonstrates that the ADL mechanism aims to prioritize those traders who achieve high profits through high leverage as risk bearers.

How to Reduce ADL Risk

Traders can take proactive measures to lower their ranking in the ADL queue, thereby avoiding the risk of being auto-deleveraged:

Reduce Leverage: This is the most direct and effective method. Lowering leverage directly reduces the "effective leverage" factor in the ranking formula, significantly lowering the ADL ranking score.

Partial Liquidation for Profit: Partially liquidating profitable positions can lower the "profit percentage" factor, effectively reducing the ADL ranking. Converting floating profits into actual gains can also lower overall risk exposure.

Closely Monitor ADL Indicator: During periods of severe market volatility, traders should constantly pay attention to their position's ADL risk indicator. If they notice an increase in the indicator level, they should immediately take the above measures for risk management.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。