Written by: Joel John and Sumanth Neppalli,Decentralised.co

Translated by: Yangz, Techub News

Today, everything can be achieved through APIs, except for peace. As long as resources are abundant, coupled with a group of caffeine-fueled developers, you can create applications for "one-click ride-hailing, hotel booking, and even scheduling psychological consultations." What if these APIs are used to reshape ancient institutions?

Today's article explores how legislative changes are deconstructing the banks we know. We believe that if blockchain is the track for funds and everything can be monetized, users will eventually leave idle deposits in their preferred applications. Over time, these balances will accumulate into mountains on platforms with significant distribution capabilities.

In the future, everything can become a bank, but how can this be achieved?

The "GENIUS Act" allows applications to represent users' holdings in US dollars in the form of stablecoins. It creates incentives for platforms, encouraging users to save money and spend directly through the application. But banks are not just "vaults" for storing US dollars; they are complex databases layered with logic and compliance. In today's article, we will explore how the technology stack driving this transformation has evolved.

In the early days of operating this newsletter, we had to change banking partners several times. After all, not many are willing to support a bootstrapped company that calls itself "Decentralised.co." After a few switches, I realized a simple truth that should have been common sense: most fintech platforms we use are essentially just "packaged" versions of the same underlying banks. Thus, we stopped chasing the next shiny payment product and began to establish direct partnerships with banks.

You cannot build a startup on top of another startup. You need to establish direct connections with entities that actually handle the business, so that when problems arise, you won't get stuck in a game of telephone with layer upon layer of middlemen. As a founder, choosing a stable but slightly traditional vendor can save you hundreds of hours and just as many back-and-forth emails.

But why is this important? Am I supposed to write a founder's operations guide? No. The entire process taught me two seemingly contradictory rules:

In banking, most profits come from where the funds are stored. Traditional banks hold billions in user deposits and have internal compliance teams. Compared to those startups still struggling for licenses, banks may be the safer choice.

At the same time, huge profits can also come from the thin middle layer of high-frequency asset movement. Robinhood does not "hold" stock certificates, and most cryptocurrency trading terminals do not custody user assets, yet they earn billions in fees each year.

This represents two opposing forces in the financial world: to choose asset custody or to become a trading layer? Traditional banks may resist the demand for "trading meme coins with custodial assets" because they profit from deposits; exchanges, on the other hand, make money by convincing you that "wealth comes from betting on the next animal coin."

Behind this contradiction is the evolution of the concept of "portfolio." My grandmother in Kochi, Kerala, would be satisfied with a combination of gold, land, and a few stock certificates. Today, a savvy 27-year-old might consider her Ethereum, Sabrina Carpenter music copyrights, and streaming dividends from "My Oxford Year" (by the way, it's a great movie) as solid additions to her portfolio beyond just gold stocks. Although copyrights and streaming dividends do not currently exist, the development of smart contracts and regulations is likely to make them a reality in the next decade.

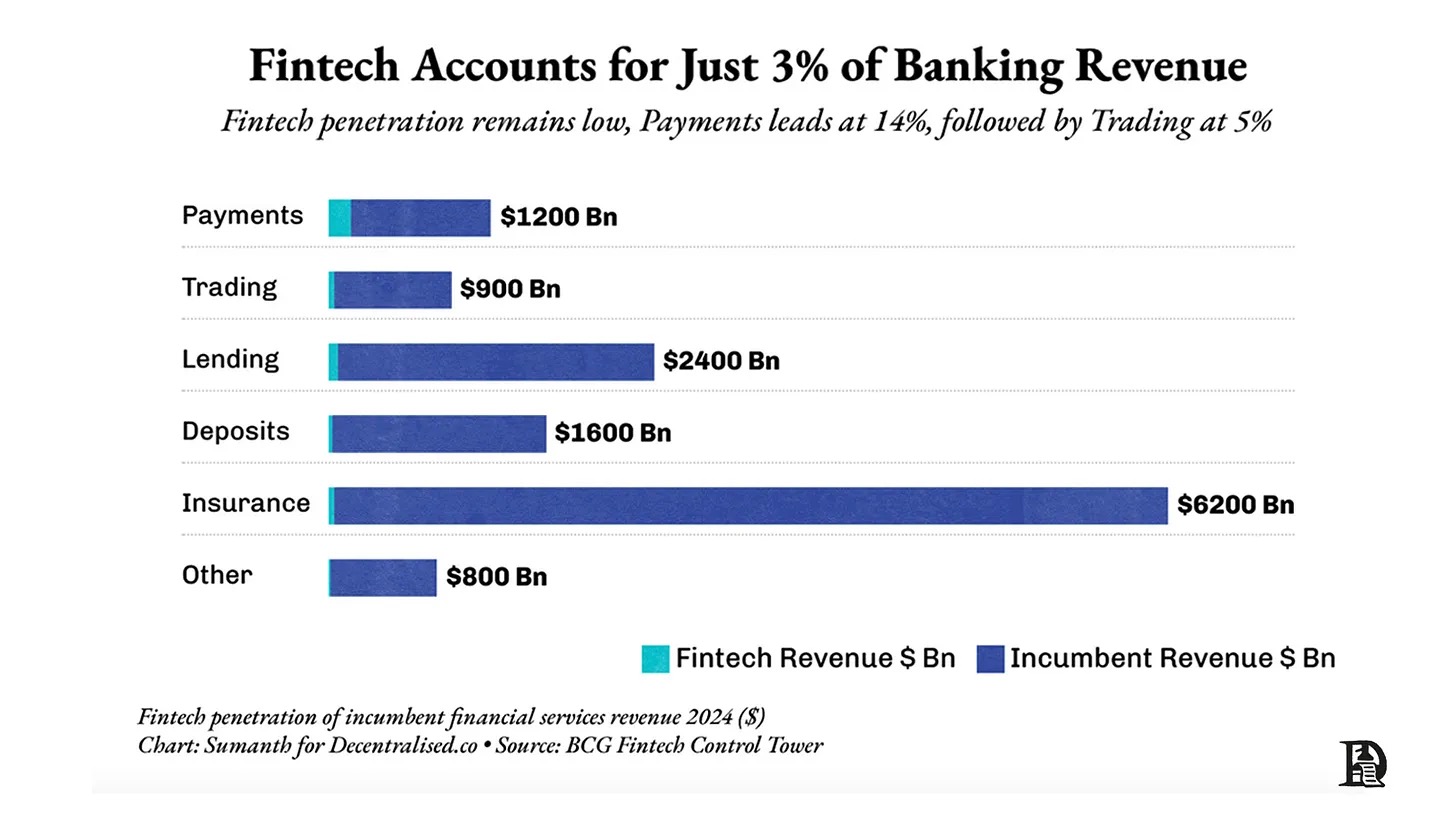

If the definition of a portfolio is changing, then where we store wealth will also change. Few fields illustrate this transformation as clearly as banking. Banks account for 97% of the revenue in the banking industry, while fintech platforms only capture about 3%. This is a textbook example of the Matthew effect—because most capital is concentrated in banks today, they earn the vast majority of the industry's revenue. But can businesses establish themselves by dismantling this monopoly and controlling specific functions?

We tend to believe in this possibility. This also explains why half of our portfolio consists of fintech startups. Today's article will provide arguments for the proposition of "deconstructing banks."

New banks are not in shiny office buildings in the city center. They lurk in your social feeds, hidden within various applications, and may even be hiding in the cookies generated by your suspicious search history from last Friday night. Cryptocurrency has matured to a stage where it is no longer just associated with early adopters; it begins to ambiguously blend with the boundaries of fintech, allowing the products we build to target the global market as potential scale. But what does this mean for investors, operators, and founders?

We will explore the answers to these questions in this issue. But first, let’s take a look at the "graveyard" of fintech startups.

The "Genius" of Liquidity

Warren Buffett is known as the Oracle of Omaha, and this title is well-deserved. The performance of the portfolio he manages is nothing short of magical, but behind this magical performance lies a set of financial engineering wisdom often overlooked by the public. Berkshire Hathaway has what is known as a "permanent capital" advantage—since 1967, the insurance business it acquired has provided stable idle funds, known in insurance terms as "float" (premiums paid by policyholders that have not yet been claimed). Essentially, this is akin to obtaining an interest-free loan that can be used indefinitely.

This stands in stark contrast to most fintech lending platforms. Take LendingClub, for example; this P2P lending platform's liquidity entirely depends on platform users. Imagine this: if I lend money to Saurabh and Sumanth on the platform and both default, I might never lend to Siddharth again—just like if you had a car accident every time you used Uber, would you continue to hail rides? It is this crisis of trust that ultimately forced LendingClub to acquire Radius Bank for $185 million to secure a stable source of deposit funding.

SoFi's trajectory is equally thought-provoking. This fintech company spent seven years and nearly $1 billion building a non-bank lending business. However, lacking a banking license, it was unable to accept public deposits and could only relend funds through partner banks, resulting in most interest income being captured by middlemen. Imagine this: I borrow from Saurabh at a 5% interest rate and then lend to Sumanth at a 6% interest rate. The 1% spread is my profit from issuing this loan. But if I had a stable source of deposits (like a bank), my returns could far exceed expectations.

SoFi ultimately did just that. In 2022, it acquired Golden Pacific Bank for $22.3 million, gaining a national banking license. With this move alone, SoFi's net interest margin (the difference between loan income and funding costs) instantly soared to 6%, far exceeding the industry average of 3-4% in the U.S. banking sector.

The profit margins for small bank "packagers" are limited, but what about tech giants? Google once launched the Plex project, attempting to embed a digital wallet within Gmail and forming alliances with financial institutions like Citibank and Stanford Federal Credit Union to handle deposit operations. However, after two years of regulatory tug-of-war, the project ultimately faded away in 2021. This reveals a harsh reality: even with the world's largest email system, it is difficult to persuade regulators to allow users to transfer funds where they send and receive emails. That's just the way it is.

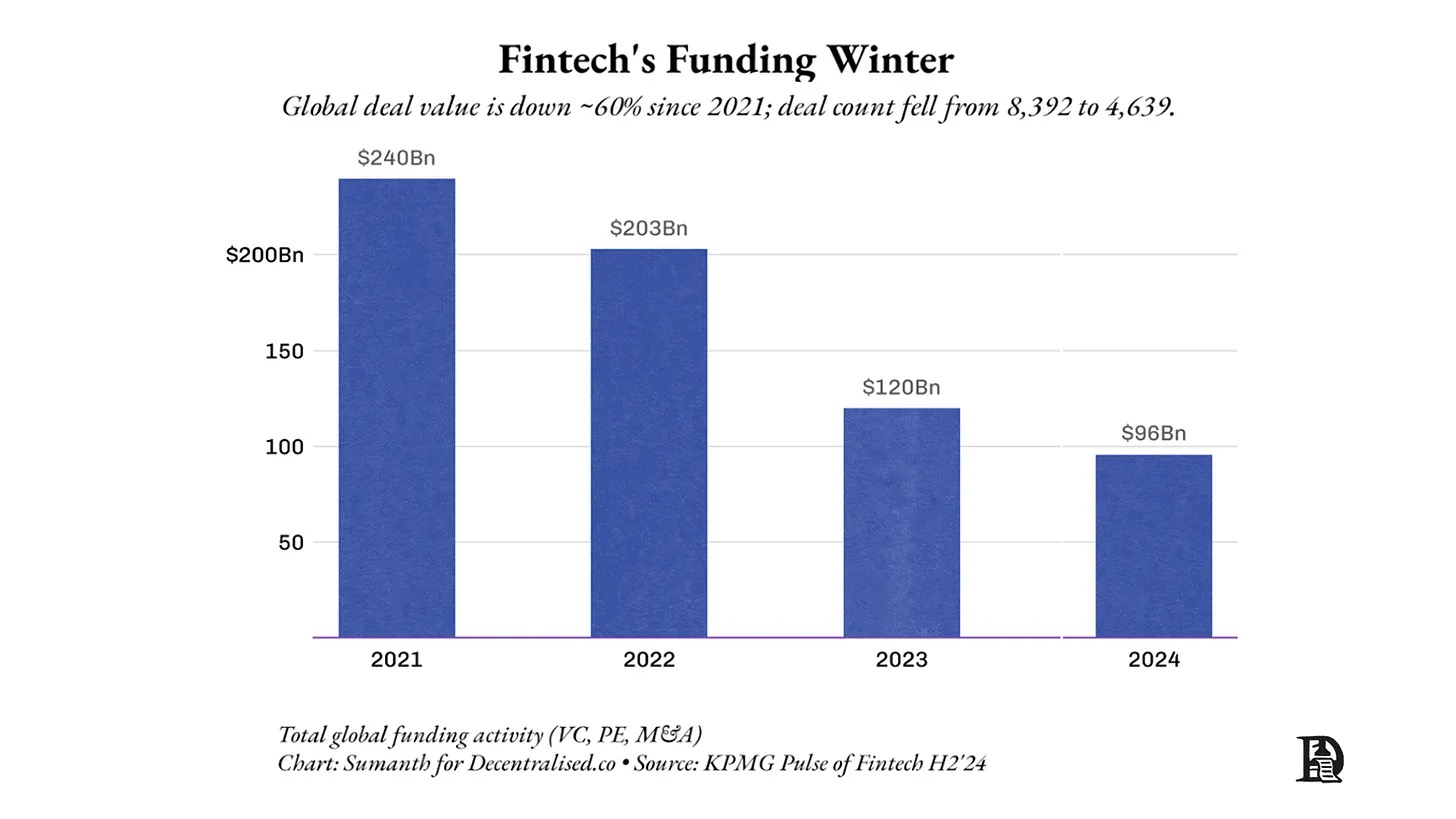

VCs have long been aware of the difficulties involved. Since 2021, the amount of funding flowing into fintech startups has been halved. Historically, regulatory charters have been the most important moat for fintech companies—this also explains why traditional banks continue to capture the vast majority of industry profits. But when the banking system experiences mispricing of risk (as seen in the Silicon Valley Bank collapse), it essentially gambles with the deposits of ordinary savers.

The "GENIUS Act" is dismantling the regulatory moat of traditional banks. It allows non-bank institutions to hold user deposits in the form of stablecoins, issue digital dollars, and achieve real-time settlement around the clock. While lending operations remain restricted, asset custody, compliance review, and liquidity management are gradually shifting into the realm of code construction. We may be entering a new era—based on these financial infrastructures, a new batch of fintech giants similar to Stripe will emerge.

But will this increase risk? Are we enabling startups to gamble with user deposits? The answer is no. The transparency of digital dollars (stablecoins) far surpasses that of the traditional financial system. Traditional financial risk assessments are closed-door operations, while all movements of on-chain assets are publicly verifiable—from ETF holdings to proof of reserves for digital asset treasury (DAT), even the amount of Bitcoin held by countries like El Salvador and Bhutan can be verified in real-time on the blockchain.

We will witness a transformation where products may look like Web 2.0, but assets operate on the rails of Web 3.0. Imagine using stablecoins with Transferwise.

If blockchain can enable faster fund transfers, and digital native assets like stablecoins allow compliant institutions to custody user deposits, we will see a new generation of banks rise with entirely new economic models. But to understand this transformation, we first need to deconstruct the components of traditional banks.

Stable Building Blocks

What exactly is a bank? Its core functions can be broken down into four basic modules:

First, it is a database that records asset ownership, clearly documenting who owns how much;

Second, it provides payment channels for transfers, facilitating the flow of funds between users;

Third, it performs compliance checks to ensure the legality of custodial assets;

Finally, it leverages data information to market value-added services such as loans, insurance, and trading.

Cryptocurrency's erosion of these functions is quite unique. Taking stablecoins as an example, while they do not possess full banking functions, they demonstrate astonishing potential in terms of transaction volume. Traditional payment giants Visa and Mastercard have long monopolized transaction channels, as merchants have no choice, and every card transaction contributes a few basis points of profit to their moat.

In 2011, the average debit card fee in the U.S. reached 44 basis points, prompting Congress to pass the Durbin Amendment to halve it. In 2015, the EU further reduced debit and credit card fees to 0.20% and 0.30%, respectively, deeming these two giants to be "colluding rather than competing." However, U.S. credit card fees have remained at 2.1%-2.4% to this day, unchanged for a decade.

Stablecoins are disrupting this economic model. On Solana or Base, the cost of transferring USDC is fixed at less than $0.20, regardless of the transaction amount. Shopify merchants receiving USDC through self-custodied wallets can save the 2% fees typically paid to credit card networks. Stripe has recognized this opportunity, with its USDC settlement rate at just 1.5%, significantly lower than the traditional payment rate of 2.9% + $0.30.

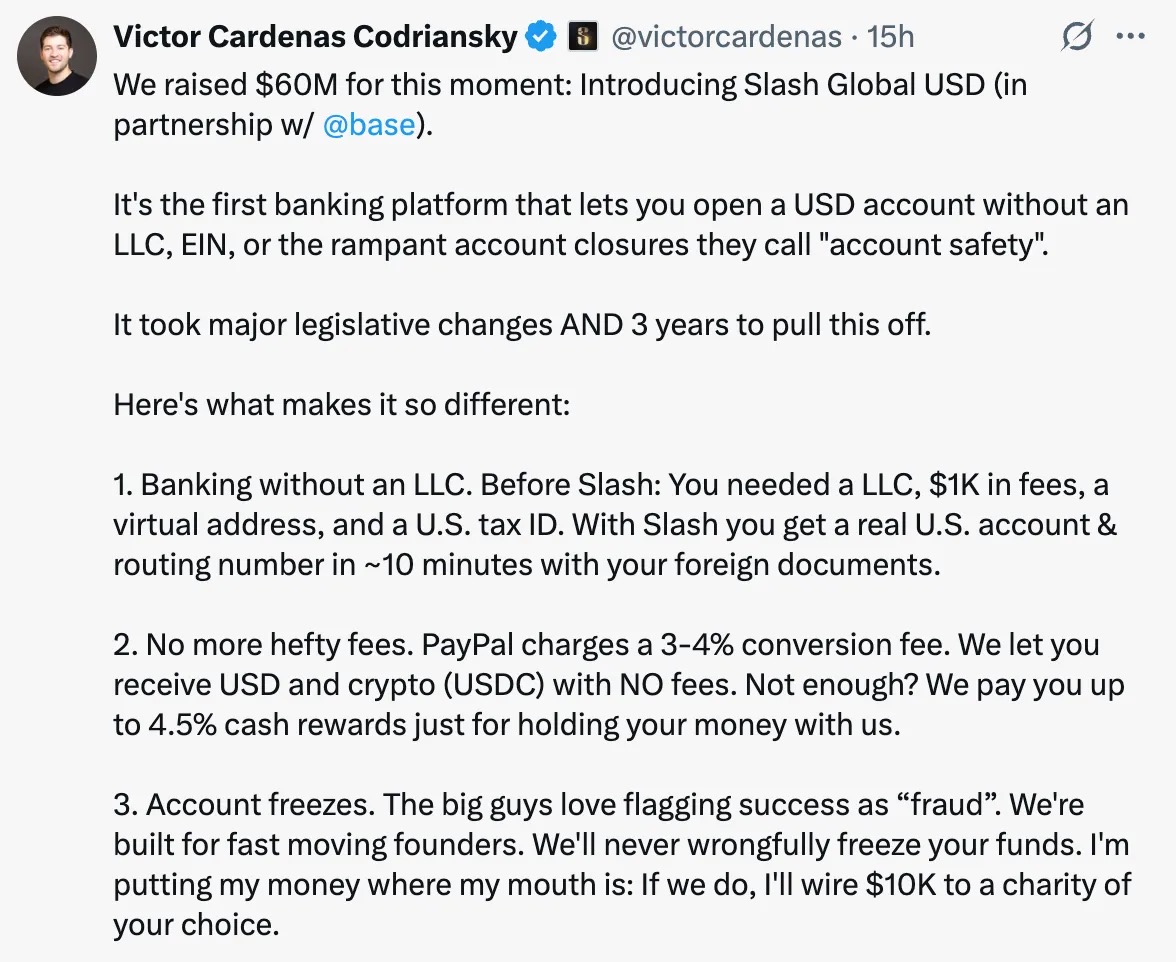

These new payment channels attract new players with very low barriers to entry. The Slash platform, backed by Y Combinator, allows any exporter to start receiving payments from U.S. customers in just five minutes—no need to register a Delaware C Corporation, sign acquiring agreements, deal with cumbersome paperwork, or hire legal services, just a digital wallet. This serves as a clear warning to traditional payment processors: either upgrade to support stablecoins or lose card transaction revenue.

For users, the economic rationale is straightforward:

Emerging market merchants accepting stablecoin payments can avoid the hassle and high costs of foreign exchange.

This is also the fastest mechanism for cross-border remittances, particularly suitable for merchants needing to pay downstream suppliers for imported goods.

It saves the approximately 2% fee charged by Visa/Mastercard in traditional payments. While there are still costs in the fiat currency exchange process, stablecoins often trade at a premium to the dollar in most emerging markets. For example, in the Indian market, USDT is quoted at 88.43 rupees, while Transferwise's dollar exchange rate is only 87.51 rupees.

The popularity of stablecoins in emerging markets stems from their clear value proposition: cheaper, faster, and safer. In regions like Bolivia, where inflation rates can reach 25%, stablecoins have become a viable alternative to fiat currency. Essentially, stablecoins give the world a preliminary taste of the potential of blockchain as financial infrastructure.

Once merchants convert cash into stablecoins, they quickly discover that the real challenge lies not in the collection process but in on-chain operational management: funds still need to be custodied, transaction flows must be reconciled, suppliers await payment, wages need to be disbursed on time, and audit requirements must be verifiable—functions that traditional banks package through "Core Banking Systems" (CBS) now require entirely new solutions on-chain.

CBS primarily undertakes two fundamental functions:

Maintaining a tamper-proof ledger: clearly recording asset ownership and linking accounts to customers.

Securely opening the ledger to external access: supporting payments, loans, credit cards, etc., while meeting risk control and reporting requirements.

Banks typically outsource this work to specialized CBS vendors. These vendors are often tech companies focused on software development, while banks concentrate on financial services. This division of labor began during the financial electronic revolution of the 1970s, when bank branches transitioned from paper ledgers to networked data centers, gradually solidifying under layers of regulation.

The Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), which publishes operational manuals for all U.S. banks, has established industry standards that require core banking systems to have primary and backup data centers located in different regions, maintain redundant telecommunications lines and power supplies, continuously record transactions, and monitor any security incidents.

Changing core systems is akin to a military defense emergency, as all customer asset data and transaction records are locked in the vendor's database. Migration means needing to switch systems over a weekend, run two ledgers simultaneously, accept surprise inspections from regulators, and face a high likelihood of system failures the day after the switch. This inherent stickiness makes core banking systems almost a permanent lease. The three major vendors (FIS, Fiserv, and Jack Henry) were all founded in the 1970s and still bind bank clients with an average of 17-year long-term contracts, collectively serving over 70% of commercial banks and nearly half of credit unions in the U.S.

The pricing of these vendors is usage-based: fees for retail checking accounts range from $3 to $8 per month, decreasing with increased usage, but value-added services can drive up costs. For example, enabling mobile banking, fraud monitoring, FedNow rapid payments, or analytics dashboards can significantly increase expenses. Fiserv alone is expected to generate $20 billion in revenue from banks in 2024, about ten times the on-chain fees of Ethereum during the same period.

When assets themselves exist on a public chain, the data layer loses its proprietary nature. Whether it's USDC stablecoin balances, tokenized short-term government bonds, or loan contracts in the form of NFTs, they are all stored on the same open ledger. If an application is dissatisfied with the performance or cost of the current "core system," it can continue operations by simply pointing the new business engine to the existing wallet address without needing to migrate terabytes of state data.

That said, the cost of conversion has not disappeared; it has merely transformed. Payroll systems, ERP software, analytics platforms, and audit processes all need to interface with the new core system. Changing vendors means reconfiguring these interfaces, similar to switching cloud service providers. The core system is not just a ledger; it also carries critical business logic, including user account mapping, settlement cut-off times, approval workflows, and exception handling. Reconstructing these logics on the new platform still requires investment, even though the assets themselves are portable.

The difference is that these frictions now belong to software engineering issues rather than data hostage situations. While it is still necessary to write "glue code" to connect different workflows, this falls within the scope of agile development cycles, unlike traditional system migrations that require years of hostage negotiations. Developers can even adopt a multi-core architecture—using different engines for retail wallets and fund management, as both point to the same standard blockchain state. When a service provider fails, failover can be achieved by quickly deploying new containers without the need for late-night data migrations.

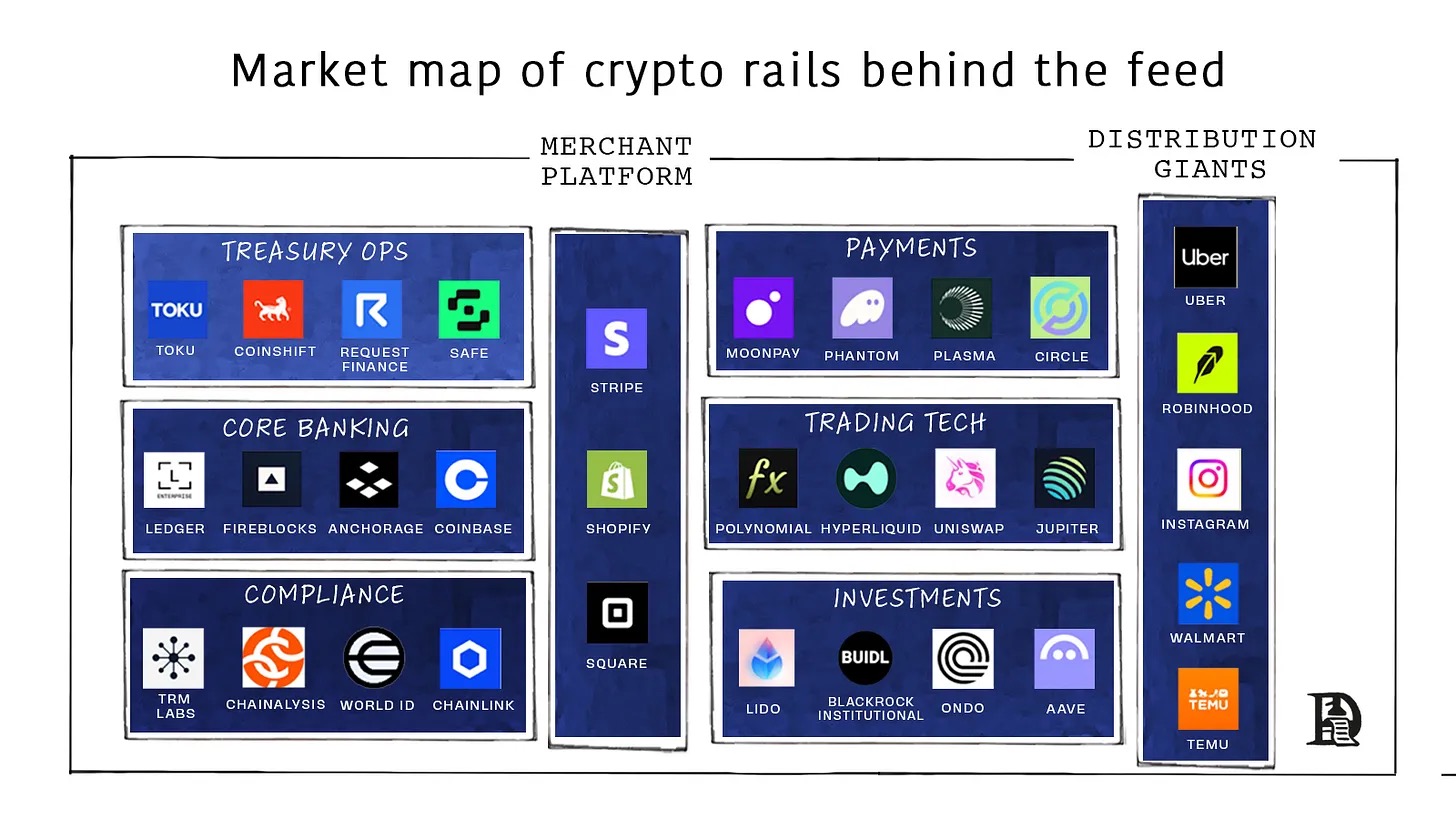

Through this prism, the future form of banks will be radically different. The current functional components exist independently, waiting for developers to integrate them into a complete solution for retail users.

Fireblocks: Safeguards over $10 trillion in on-chain asset flows for banks like BNY Mellon, with its strategy engine supporting stablecoin minting, routing, and reconciliation across over 80 chains.

Safe: Custodies approximately $100 billion in smart account assets, with its SDK offering passwordless login, multi-signature strategies, gas fee payment, real-time payroll disbursement, and automatic rebalancing.

Anchorage Digital: As the first licensed crypto bank, it provides compliant balance sheet services supporting Solidity language. Franklin Templeton has directly minted its short-term government bond fund within the Anchorage custody system, achieving T+0 share settlement (traditional systems require T+2).

Coinbase Cloud: Offers transfer services for wallet generation, multi-party computation (MPC) custody, and compliance screening through a single API.

These emerging platforms possess key capabilities lacking in traditional vendors, including a deep understanding of on-chain assets, built-in compliance anti-money laundering mechanisms, and event-driven real-time APIs (as opposed to traditional batch processing). Facing an opportunity where the market size is expected to grow from the current $17 billion to $65 billion by 2032, the conclusion is clear: business lines once monopolized by traditional players like Fidelity are being redistributed, and those new enterprises programming in Rust and Solidity (rather than Cobol) will emerge as the biggest winners.

However, before they can truly serve the mass market, they must overcome the ultimate demon that all financial products face—compliance. In an increasingly on-chain world, what form will compliance mechanisms take?

Codified Compliance Mechanisms

Traditional banks primarily perform four types of compliance operations, including customer identity verification (KYC and due diligence), counterparty screening (sanctions and PEP checks), monitoring of fund flows (transaction alerts and investigations), and regulatory reporting (suspicious activity reports/large transaction reports and audits). This system is large in scale, costly, and operates continuously. In 2023, global compliance spending surpassed $274 billion, with the burden increasing almost every year. FinCEN processed approximately 4.7 million suspicious activity reports and 20.5 million large transaction reports last year—these are all paper documents submitted after risks have occurred. Traditional compliance is essentially batch processing: collecting PDFs and logs, organizing narrative materials, submitting reports, and then waiting.

Blockchain transactions transform compliance from a pile of documents into a real-time system. The FATF "travel rule" requires transfers to include information about the sender/beneficiary (traditional finance exempts transactions below $1,000/euros), and the EU has extended this rule to all crypto transactions. On-chain, this data can be transmitted as encrypted attachments with the transaction—visible to regulators but not to the public. Chainlink and TRM provide real-time sanction lists and fraud oracles, automatically querying the lists during transaction execution; if an address is flagged, the transaction is immediately rolled back.

When using zero-knowledge proof wallets like Polygon ID, users can carry encrypted credentials (such as "over 18 and not on the sanctions list") without revealing their passport or address. Merchants see a verification passed sign, regulators receive audit trails, and user privacy is protected.

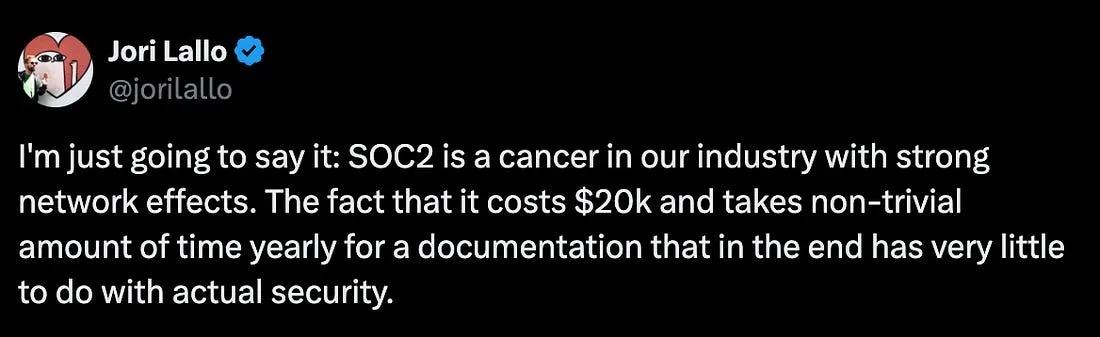

If funds are trapped in backend paperwork, even the fastest-moving market is meaningless. Vanta is an example of a regulatory tech startup that shifts SOC2 compliance from consultants and screenshots to APIs. Startups selling software to Fortune 500 companies need SOC2 certification, which is meant to prove that companies follow reasonable security practices to avoid storing customer data in unprotected public links like Tea.

Traditionally, startups needed to hire auditors to submit massive spreadsheets, requiring screenshots of everything from AWS setups to Jira tickets, only to return six months later with a signed PDF that was already expired. Vanta simplifies this cumbersome process into an API: no need to hire consultants, just integrate Vanta with AWS, GitHub, and HR systems; it automatically monitors logs, takes screenshots, and submits them to auditors. This simple innovation has propelled Vanta to achieve a $200 million APR and a valuation of $4 billion. However, while this innovation is indeed practical, it essentially optimizes the "screenshot tax."

The financial industry will undergo a similar evolutionary trajectory: reducing paper file management, shifting to real-time policy engines that assess transaction events, and generating cryptographic proofs. All asset balances and fund flows will carry timestamps and digital signatures, transforming audit work from sampling checks to continuous supervision.

Oracle networks like Chainlink act as "truth transmitters" between off-chain regulatory rules and on-chain execution. Their proof of reserves (PoR) data streams allow smart contracts to verify collateral sufficiency in real-time, enabling issuers and trading platforms to set up automatic circuit breakers. Ledgers will no longer wait for annual checks but will be in a state of continuous monitoring. Proof of reserves will update collateral levels block by block. When the collateralization ratio of a stablecoin falls below 100%, the minting function will automatically lock and notify regulators immediately.

Of course, real challenges still exist: identity verification, cross-jurisdictional rules, edge case investigations, and machine-readable policies all need to be strengthened. The evolution of compliance in the coming years will resemble API version iterations: regulators will issue machine-readable rules, oracle networks and compliance vendors will provide reference adapters, and audit modes will shift from sampling to continuous supervision. As regulators gradually understand the value of real-time audits, we will witness the birth of a new generation of compliance tools—not just to pass paper checks but to build a true financial security infrastructure.

A New Era of Trust

Everything is first bundled and then unbundled. Human history is a repetitive process of trying to enhance efficiency through the integration of things, only to discover decades later that separation is the optimal state. The current legislative status of stablecoins and the development stages of underlying networks (like Arbitrum, Solana, and Optimism) mean we will witness the continuous reorganization of banking functions. Recently, Stripe announced its attempt to build L1.

Two forces are simultaneously at work in modern society:

Cost increases due to inflation

The meme desire spawned by a highly interconnected world

In this era of inflated consumer desires and stagnant wages, more and more people are taking control of their finances. The GameStop short squeeze, the surge of meme coins, and the buying frenzy for Labubu and Stanley thermoses are all byproducts of this shift. This means that applications with a sufficient user base and trust will evolve into banks. We will see the builders of Hyperliquid's code system expand into the entire financial world—ultimately, those who control the traffic entry points will become banks.

Why trust JPMorgan when your most trusted Instagram influencer recommends a portfolio? Why use Robinhood when you can trade directly on Twitter? Personally, I might choose to buy rare books on Goodreads to lose money (laughs). The key is that the "GENIUS Act" has changed the legal framework for products holding user deposits. When the components of banks become API calls, more products will possess banking functions.

Platforms that have information flow will be the first to undergo this transformation, and this is not a new phenomenon: social networks have relied on e-commerce platforms for monetization since their early days because that is where the flow of funds occurs. When users see ads on Facebook and shop on Amazon, it creates referral income for the former. The Beacon app launched by Amazon in 2008 generated wish lists by tracking platform activity. Throughout the history of the internet, there has always been a subtle balance between attention and commerce. Embedding banking infrastructure into their platforms will become another mechanism closer to the source of funds.

Will traditional forces sit idly by in the face of this trend? Can existing fintech companies remain indifferent? FIS is closely communicating with major banks, clearly understanding the changing situation. Ben Thompson presented a simple yet brutal perspective in his latest article: when paradigms reverse, former winners find themselves in trouble because they cling to the practices that brought them success, optimizing for the old game, defending outdated KPIs, and making "correct" but outdated decisions in the new world. This is the "winner's curse," applicable in the era of funds moving on-chain.

When everything can become a bank, there will be no banks left. If users do not concentrate their wealth on a single platform, the storage of funds will become decentralized. Crypto-native users have long stored most of their assets on exchanges rather than banks. This means that the unit economics of bank revenue will change drastically—lightweight applications may not require the same high revenue as traditional banks because their operations need almost no human intervention. But this also signals the decline of traditional banks.

In 2001, the chain bookstore Borders handed over most of its online business to a small company founded by a hedge fund manager—Amazon. A decade later, book purchases became fully digital, and Borders faded away in the era of Kindle and iPad. Many traditional financial institutions will repeat this fate. Of course, giants like JPMorgan may survive, and the cases of Visa and Mastercard show that leading players will drive change. But most small and medium-sized institutions will ultimately be swallowed by the wave of technology.

Perhaps, like life itself, technology is merely a cycle of creation and destruction. It is both bundling and unbundling.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。