Written by: Joel John, Decentralised.co

Translated by: Yangz, Techub News

Preface: The cryptocurrency ecosystem faces the risk of excessive financialization, making it difficult to achieve scale expansion beyond its initial development. The next generation of scalable products will have trading functions that are just a small part of their product characteristics. To scale Web3 applications, we need to build products that encourage users to continue using them for non-trading reasons. Just as only 1% of users on the internet publish content, in the future, perhaps only 1% of users will engage in transactions within Web3 native applications. Cryptocurrency is not only a culture but also a medium of expression. To drive the entire industry towards scalability, entrepreneurs must focus on both dimensions simultaneously.

I often wonder what Michelangelo was thinking while painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Undoubtedly, it is one of the greatest artistic treasures in human history, but initially, he shied away from this commission—true art, to him, belonged to marble sculpture. Chiseling, stone, and the human form were his true domains.

When he received this task, Michelangelo was heavily in debt due to his failure to complete a sculpture for a deceased pope on time. Meanwhile, Pope Julius II commissioned him to paint the chapel. Michelangelo viewed this task as a trap set by his rival, as the project was extremely daunting, and failure would lead to ridicule. He found himself in a dilemma, caught between the commissions of a deceased pope and a living one, unable to move forward or backward.

However, in that era, no one could simply walk up to the leader of the Catholic Church and say "no." So he accepted the commission, and from 1508 to 1512, he spent four years painting that ceiling. He loathed the job so much that he even wrote a poem describing himself as a curled-up cat. What caught my attention most was this part of his poem:

"My painting is dead.

Giovanni, please defend it for me, guard my dignity.

I do not belong here—I am not a painter."

This sentiment may be familiar to anyone who has dedicated their life to art: the pressure of looming deadlines, having to do work that goes against one's original intentions, and doubts about one's own worth. But what we must remember is that while saying "I am not a painter," this person was creating culture and history.

Did you notice the name mentioned in the poem? Giovanni? It refers to Giovanni da Pistoia. But for us, there is another Giovanni worth noting—Giovanni Medici. He was Michelangelo's childhood friend, and they grew up together. Young Michelangelo entered the Medici Palace with the support of Lorenzo de' Medici.

The Medici family was a prominent banking dynasty in medieval Europe. We might consider them the JPMorgan or SoftBank of the 15th century—except they were actually the financial architects behind the Renaissance, the "godfathers" of this game.

520 years later, I sit here writing about Michelangelo partly because some influential bankers stood behind him at that time. Throughout history, capital or money has always intertwined ambiguously with art, shaping the culture we recognize. Most of the artistic treasures revered by society have substantial capital backing them. Michelangelo may not have been the most outstanding artist of his time. There may have been countless artists better at capturing human emotions, quietly fading away with time. Part of this is because they never entered the core circle of capital, and another part is that some artists left their best works forever in the draft box. (Please publish them!)

When you connect all of this with the way modern media operates, it becomes even more interesting. The "Sistine Chapel" of our time is not in Europe but on the internet. Every time you log into X, Instagram, and Substack, you are stepping into these chapels. And the "Michelangelos" of our era no longer wait for the favor of the Medici family; they indeed hope that algorithms will be on their side. The "Medici" of modern society choose to buy the entire chapel and put their faces on it. Just like Musk significantly increased the visibility of his posts a few months after acquiring X. New gods are building their own chapels.

Technology can accelerate the pace of cultural change. In this era of nine-second short videos, memes are like building blocks for constructing culture. But it also relies on capital to achieve scalability. Without billions of dollars in funding, and without regulations that protect founders from imprisonment due to platform content, we wouldn't even be discussing platforms like Facebook. Imagine if you could sue Zuckerberg because your distant uncle posted a racist meme on Friday night?

Today, technology has become a lever for changing culture, expanding the ways humans express themselves. All technologies change the medium of expression while leaving their mark on culture.

I have been pondering how technology, culture, and capital have intertwined over time. As a technology scales, it attracts capital; and in this process, technology gradually converges its modes of expression. For example, we no longer advocate for radical decentralization but discuss more optimized unit economics in the crypto space; we no longer condemn banks as evil but praise how they distribute digital assets. This shift fascinates me; it influences everything, from the funding narratives of entrepreneurs to how chief marketing officers define brand storytelling.

But before delving deeper into this, let’s briefly review the evolution of media itself.

Evolution

Humans are machines of expression. From the moment we learned to squeeze juice from leaves to leave graffiti in caves, we have been leaving marks of what we wish to express—depicting animals, outlining deities, portraying lovers, and expressing desires and despair. As the medium of expression gradually formed a network, human expression became more vivid and dynamic.

You may not have noticed, but our logo features a printing press—specifically, a hand-cranked printing press. This is not only a tribute to Gutenberg but also a metaphor for the potential irony in information dissemination. At the end of the 15th century, when Gutenberg printed the first Bible, he could hardly have anticipated how his invention would ignite a revolution in information dissemination.

For instance, by the 17th century, almanacs (or dense scientific literature) had become a major form of reading material in Europe. The printing press facilitated the efficient spread of ideas, which was a crucial force behind the scientific revolution. From then on, humans could freely declare that "the Earth is not the center of the universe" without fear of punishment for their words.

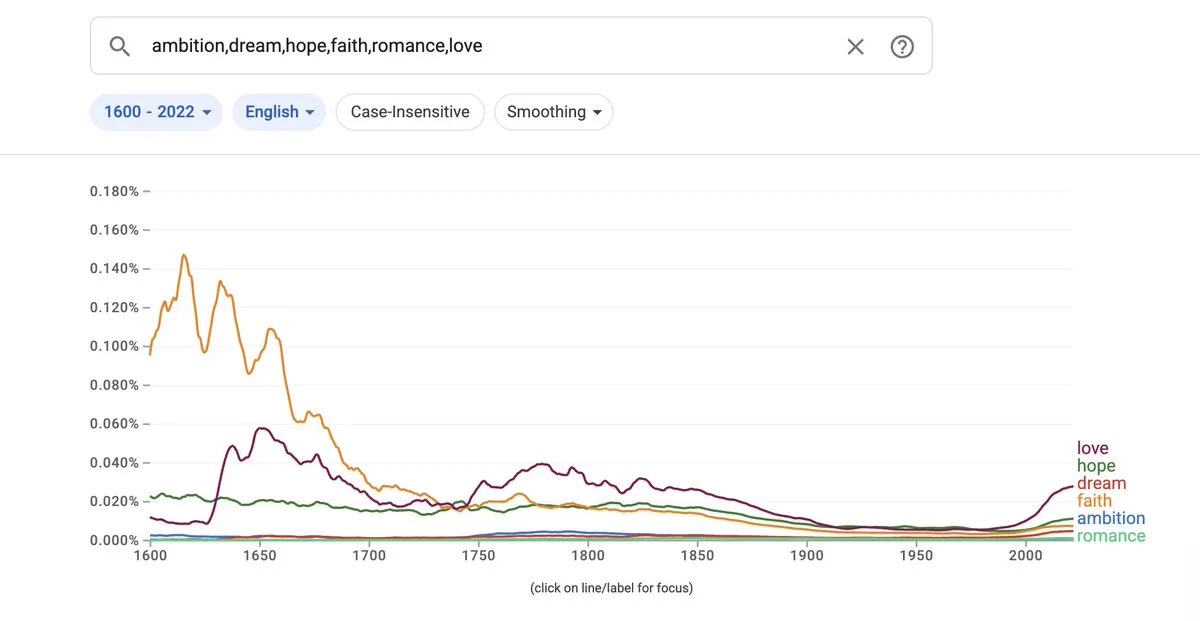

As seen in the above image, references to "faith" in literary works gradually decreased, replaced by the theme of "love." Of course, this does not mean that all of Europe abandoned religion in pursuit of better life partners; rather, the nature of the medium of dissemination underwent a fundamental change. The tools initially used to spread faith (the printing press) may have accelerated the decline of faith.

The printing press symbolizes that once a technology or medium of information is activated and released, its application trajectory may exceed initial expectations.

It shifted the written medium from a public product to the private sphere. Around the 18th century, people gradually stopped reading aloud and began to read silently in the quiet of their bedrooms. This transition makes sense because, before the widespread availability of printed media, books and literacy were not common. Therefore, reading at that time was a social activity where people gathered, and one person read aloud from a book. As book prices gradually decreased and the aristocracy had more leisure time, silent reading became increasingly common.

At that time, due to the inability to control the spread of ideas through books, society even experienced a certain degree of moral panic. Parents worried that teenagers would spend their free time reading romance novels instead of engaging in the industrial revolution. It is evident that the medium shifted from public affairs to the private sphere—from public displays in temple sculptures and monasteries to privately held printed booklets. This transition also changed the nature of the ideas being disseminated: content shifted from deeply religious themes to scientific, romantic, and political topics. Ideas in these fields could hardly be widely disseminated through private discourse before the advent of printed media. The church, kings, and the aristocracy had no reason to publish papers on "how power operates."

This may have also contributed to the political upheaval at the end of the 18th century—both France and America believed the time had come to change the way they were governed. Of course, we need not get too bogged down in details, as there is still a century of media evolution to sort through, including radio, television, and the fascinating internet itself!

The nature of monetization will change how media operates in the next century. Media products like radio and television rely on having as many listeners or viewers as possible at any given moment. This means that content cannot focus solely on a niche area. Prime-time television shows are almost always news briefings rather than steamy romance stories because that is the content families watch together. Moreover, the viewpoints disseminated are almost always consistent with what is socially acceptable at the time. (This scene in The Crown perfectly captures how television as a medium brings the queen closer to the people.)

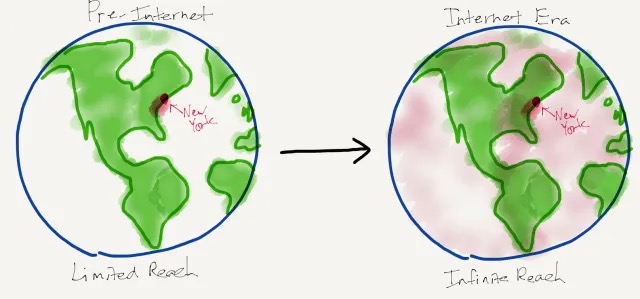

Ben Thompson brilliantly captured this shift in his article on never-ending niches. In the 1960s, I might not have had any channels to write about emerging technologies (like debit cards) and find enough audience online. As a creator, I could only focus on meeting the needs of a specific regional audience. The internet completely changed this situation, allowing me to find people interested in the digital economy worldwide. Our audience comes from 162 countries, thanks entirely to the power of the web. This scale also influences how culture is disseminated.

There are common characteristics among J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter, Jay Z's album Blueprint, and Dr. Dre's headphones. They are all exquisite artistic creations, but through the accumulation of popularity, they ultimately became centers of capital aggregation. In this process, they formed a virtuous cycle: capital helps spread art, and art, in turn, aids in capital appreciation. But a common element behind these transformations is technology.

YouTube, Kindle, and Apple Music have helped spread their works to a global audience. Culture is no longer centered around the cities they inhabit; instead, it is art consumed and recognized by an international audience. This greatly expands the audience size, thereby improving unit economics; these platforms, in turn, benefit from the users of these products.

When you try to attract a large number of users to a product, a shared culture is the most effective leverage. I previously wrote about how SuperGaming utilizes well-known brand IPs to achieve gaming scalability. As of this writing, their downloads have slightly exceeded 200 million.

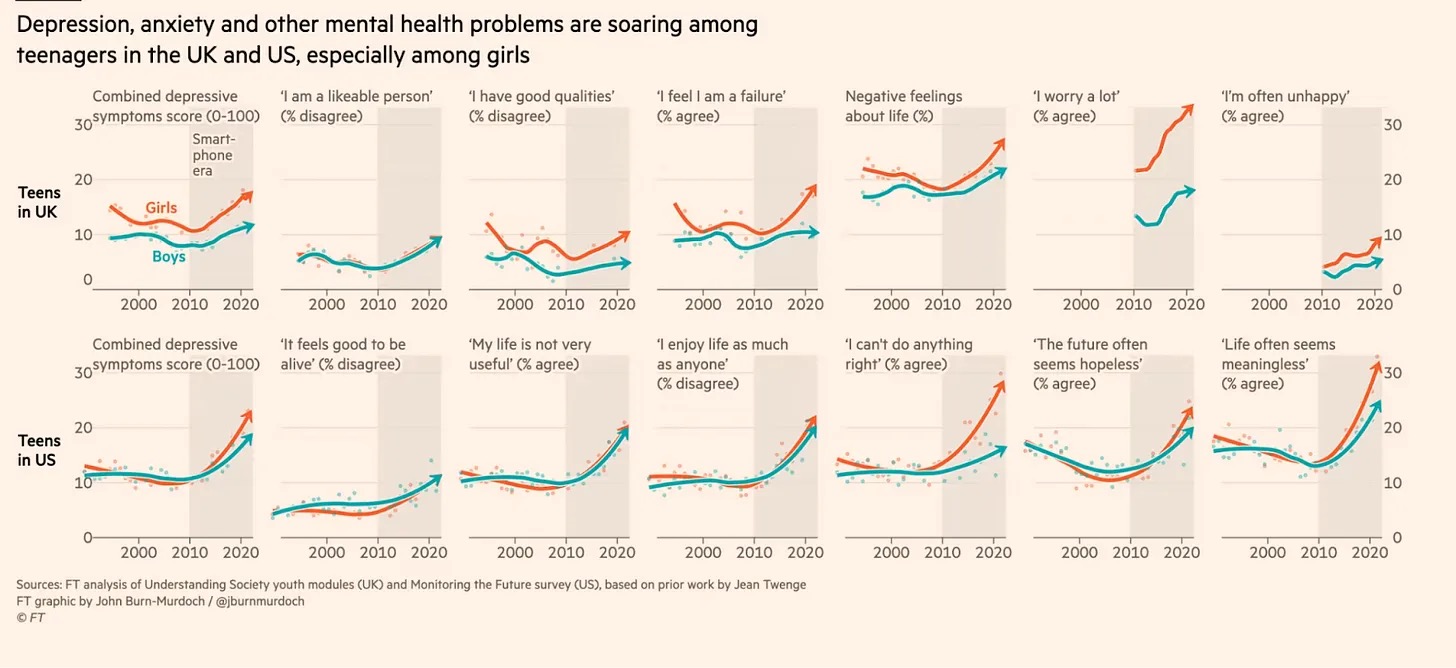

In the era of artificial intelligence and algorithmic recommendations, culture tends to centralize. Today's teenagers no longer actively seek new media; instead, they may find themselves caught in a vortex of content that further reinforces their existing worldviews. Large language models (LLMs) exacerbate this risk—users no longer encounter fragments of media created by humans but instead converse with chatbots that reinforce their inherent beliefs. This can lead to fatal consequences, including suicide. On the other hand, the same tools are increasingly being used for psychotherapy.

This is the duality of internet technology. On one hand, it allows boys from small towns in India to discover the greatest artists and aspire to become them; on the other hand, it is also the best breeding ground for spreading harmful ideas, trapping people in a continuously reinforcing vortex of content. This is why society is becoming increasingly fragmented; what we gain is not dialogue but algorithmic reinforcement.

What we have is no longer the transmission of knowledge but rather fragments of content. To gain traction in small circles, we sacrifice depth. As long as it brings clicks, who cares about the truth?

When everyone has only fifteen seconds of fame, we replace the nuanced texture of stories with catchy melodies and dazzling moments. Those stories, emotions, and virtues passed down through generations are compressed into quick dopamine hits during meeting breaks. The human experience has turned into an endless scroll, like continuously pulling the lever of a slot machine in a modern casino, searching for content that resonates. The stories grandmothers once told their grandchildren have vanished, now generated by Google Gemini, as no one is willing to invest the time and patience anymore.

We have exchanged heartfelt love letters for witty pickup lines on dating apps—trading limited entities created with effort for an infinite void generated by machines. But how does all this map to the cryptocurrency space? To understand this, we need to examine the evolution of this industry.

Transformation

From Michelangelo to Jay Z, from the Medici family to SoftBank, the trend of capital aiding cultural scalability is evident. When culture gains monetary stability, more people will accept it. Technologies like the printing press, broadcasting, or the internet help disseminate culture. Capital is needed both to create art and to establish channels for its distribution.

But what happens when the medium of expression itself is currency? This is precisely the question that cryptocurrency seems unable to answer, yet it is a question worth trillions of dollars.

The original intent of crypto was to replace banks with cypherpunk values. Given that many people on the mailing list where Satoshi sent the Bitcoin white paper had faced difficulties due to their cryptographic work, this is understandable. In the early 1990s, exporting encryption software was likened to exporting nuclear weapons. Thus, it is easy to see why there was deep-seated suspicion and hatred towards the government in the early days.

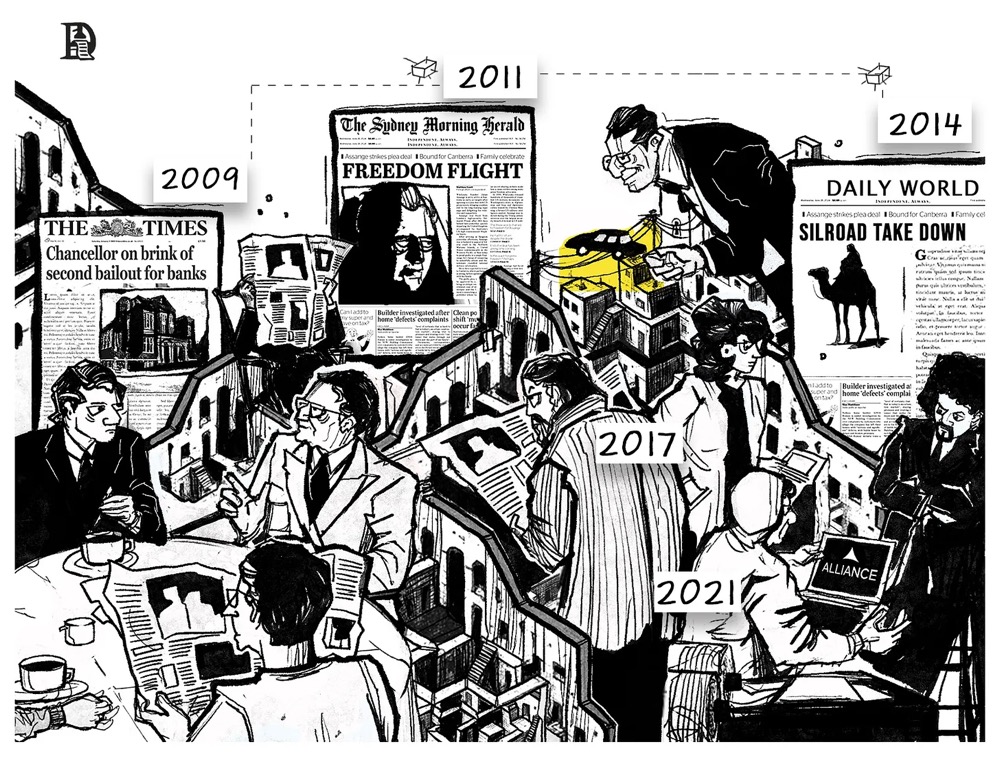

The early adopters of Bitcoin were not fintech enthusiasts but rather drug markets like Silk Road and companies like WikiLeaks that were shut out by banks. When WikiLeaks accepted Bitcoin after being banned by PayPal, Satoshi hinted that they had poked a hornet's nest. It was still 2011, and Bitcoin was still on the fringes. As an industry, cryptocurrency began to gain attention with the 2014 Ethereum ICO. The March 2017 ICO of Cosmos laid the groundwork for the subsequent boom of trying to move everything onto the blockchain.

Uber? On the chain. Tinder? Yes, on the chain. Local governments? They need to be on the chain too! We want to put everything on the chain and tokenize it because the world needs more decentralization. (Just kidding, but with a hint of sadness.)

During the ICO boom, two factors were at play. First, smart contracts on Ethereum made it easy to issue, transfer, and trade assets; second, there was a novel idea of on-chain capital formation. Founders could bypass the evil venture capital firms and raise funds from the "community." Or, they could raise funds from those intending to profit from selling tokens.

ICOs allowed venture capital firms to gain liquidity for equity investments while bringing retail participants into the fold. The great promise at the time was that venture capital as a business model would be disrupted. At that time, culture revolved around how shared ownership of assets (often tokens) and distributed governance (often through DAOs) could lead to better outcomes. Like many chapters in financial markets, that era was filled with stark optimism—until asset prices fell.

As the market evolved, cryptocurrency users split into two types: one group consisted of quantitative traders, while the other was made up of ordinary users known as "farmers." Quantitative traders were mostly seasoned traders who created wealth by leveraging pools of capital, information channels, and a general understanding of finance. "Farmers" were traditional users in cryptocurrency who contributed raw labor to protocols. I consider myself a farmer because most of my cryptocurrency comes from labor contributions to protocols (in the form of IP). Additionally, the long-tail users of farmers are those who put in extra effort for airdrops.

At that time, you didn't even need to issue tokens. You could just call them points and sell a dream. However, with the cold, harsh bear market arriving, we shifted from wanting to overthrow the government to hoping for airdrop subsidies.

Suddenly, everything was no longer about decentralization but about which token could be considered the most valuable. This mirrors the evolution of media itself. As I explained earlier, it shifted from a private consumption medium to a social reputation medium. The ICO craze cooled down in 2019, and no one could raise funds simply by issuing tokens anymore.

However, the signaling mechanisms were also evolving. The market began to price tokens based on which venture capital firms invested and which exchanges might list the token.

Like any nascent industry, we were groping for our voice. Should I call everyone "ser"? Should I really attend this DAO call? Who cares? We witnessed founders buying mansions with DAO tokens and saw Snoop Dogg purchasing real estate in the metaverse. Maybe I should go check out his plot and see if Dr. Dre is still that Dr. D.R.E.

We mistook a large group of members in Discord chats for a community. We argued that tokens are products, and their prices are indicators of product-market fit. We ignored the fact that protocols valued in the billions often generate less than $100 in revenue daily. We confused the ability of founders to discuss issues with their ability to execute solutions. Most importantly, we mistook technical jargon for signs of novelty and capability. When Bitcoin surged after the ETF craze while most altcoins did not follow suit, we woke up to this harsh reality.

The revival of meme coins in 2024 symbolizes a market awakening: volatility has always been the real product. As long as the numbers go up and there is a sense of fairness in how these assets are issued, people will come to trade. Amid WIF, Fartcoin, and various meaningless assets, we realized that sometimes speculative assets are also a medium of expression. The common sentiment among all these assets conveys the same message: a thirst for profit.

Crypto culture has shifted from focusing on ideology or technology to the behaviors it unleashes. The focus has turned to trading. If the blockchain is a track for funds, then the core purpose should be to move funds quickly and efficiently. Everything else is a distraction. However, the alternatives that have emerged in this process are happily gazing at us, showing signs that the crypto space is forming a parallel culture.

Most scalable products leverage behaviors that may seem strange from the outside. Layer3 can easily be mistaken for a platform used by airdrop "hunters." However, if you closely examine their business, you will find that they have built a complete solution for millions of users to access Web3. They provide on-chain reputation tools, wallets, exchange functions, and support for the maximum number of chains. What could have been seen as a task platform has now become a decisive tool for early product growth. (I say this because our own startup portfolio frequently uses them.)

Similarly, NFTs were once considered "dead." But Pudgy Penguins proved the exact opposite. They partnered with Walmart to create over 10 million dollars in revenue, and the brand asset has garnered nearly 120 billion views. Pudgy adopted a crypto-native foundational element but made it relevant in a completely different way. They collaborated with retail stores and leveraged Web2 social networks to attract attention.

These two products raise a question: what is crypto culture? Is it mindless meme coin speculation? Is it being liquidated daily on perpetual exchanges? Or is it betting everything on a token released just last night because AI will disrupt the job market, and we have less than two years to escape the permanent middle class?

The market has provided an answer. Cryptocurrency is both a medium of expression and a trading culture. Consumers have accepted its ability as a stable value transfer tool, which is why stablecoins have become the dominant mechanism for global capital flows. At the same time, it has also rejected some other ideas. For example, play-to-earn has catastrophically faded away. While I would love to see differently, content tokens currently show no progress. I check the content shared by friends on Instagram every day, yet I have no idea what my content on Zora is worth. (This is quite sad).

Just as there is no true freedom of speech without some offensive remarks, global resource coordination may not exist without bad actors exploiting the market. In both cases, actions have consequences. If you perform poorly for too long, no one will listen to you or buy the assets you issue. Ironically, Crypto Twitter may be facing both of these consequences simultaneously.

It is important to recognize that the evolutionary trajectory of crypto mirrors that of most media. We do not need to know the thousands of books that have become irrelevant; the internet is filled with millions of blogs that no one knows or cares about. Social media is effective because the content people express often fades within a day. The same can happen with crypto assets. There are over 40 million tokens, many of which will return to their fair value—zero. Content tokens may one day be remembered, just as people often reminisce about NFTs from 2021 or ICO tokens from 2017.

Irrelevance is the norm for most things—unless culture is involved. Culture is often defined by its modes of communication, and the words we use shape how we feel and understand the world around us. Until 2021, people could still speak in jargon. However, as we break through the boundaries of core niches, we will have to reduce our use of jargon and use language that resonates more with people—this is the art form we have been trying to refine at Decentralised.co.

For example, dating apps cannot just talk about how they are driven by zk-proof; people just want to date. The competition among stablecoins is not about how many networks they support; people are simply choosing the mechanism with the lowest global transfer costs and the fastest speeds. Consumers care about what is offered today, not the various hypothetical layers that may be realized in the future.

The closer our industry gets to consumer goods, the more we need to communicate in a language that the general public online can understand. Since the development of language often depends on the group a person belongs to and the frequency of interaction among them, we will have to change the way these consumers are onboarded and retained.

The new Medici family will be merchants of attention, while the new Michelangelo will be artists defining the flow of capital.

Redemption

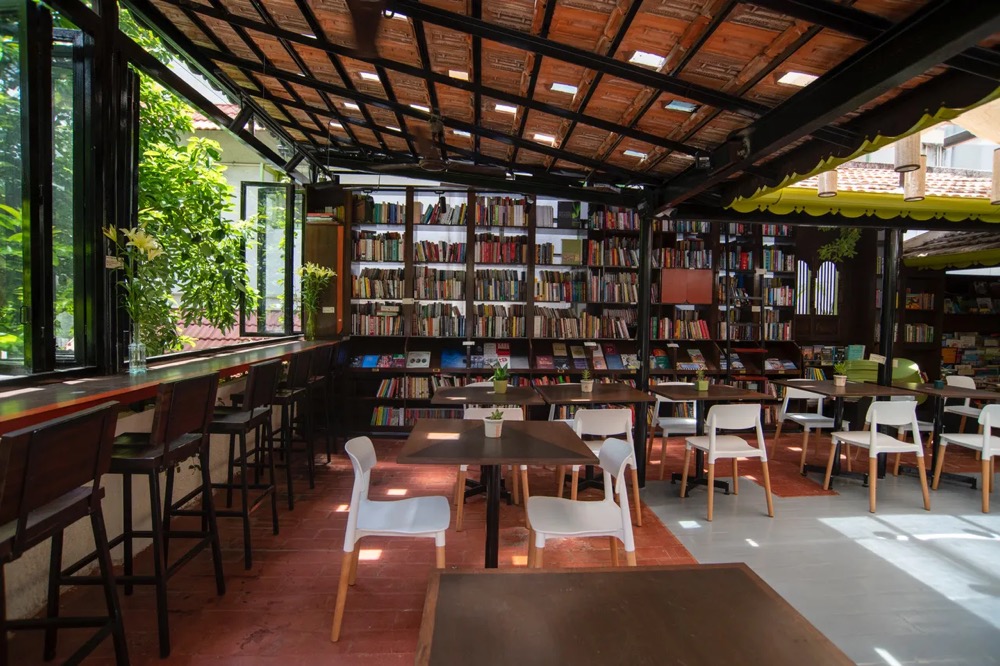

One way to understand cryptocurrency is to view it through the lens of casinos and your community café. Casinos are indeed environments with high capital flow—people frequently transfer funds across various products, but the house often wins. You do not see people lingering in casinos for long, at least not most people. In contrast, community cafés attract people day after day.

Typically, the same group of users gathers under the pretext of coffee. They share stories and the trivialities that trouble them. The tranquility and joy provided by this space are what draw them in. In more religious societies, temples or churches play a similar role. Coffee or faith becomes the medium that brings people together, but the reasons they stay go far beyond the underlying product.

Culture is a collection of stories that people share with one another. But today, the stories we share are often price charts. When these price charts turn red, people have little motivation to "return." How do we keep people coming back? What leverage do we have to bridge this technology across the chasm?

To understand this, perhaps we should look at the internet itself. Two forces are shaping the web:

One is the vast amount of content created in the age of artificial intelligence and LLMs. When everyone is a creator, no one is a true creator. People will need mechanisms to own, monetize, and distribute their content.

The other is verifiability. Endless AI-generated garbage is effective in the attention economy (like X or Instagram) because it keeps people engaged for longer. More eyeballs, more clicks, more dollars.

Everything cryptocurrency can do for the internet can be distilled into verifiability and ownership functions. These ideas are not new; we have been discussing them in this publication since 2023. However, the changing regulations and the attitudes of capital allocators are the main reasons to pursue these opportunities now.

The internet has always been a tool for free expression. Cryptocurrency enables people to own the channels and networks that create these expressions, and it also allows for the free issuance, trading, and holding of assets. When everyone gains the ability to monetize their expressions, the meme coin frenzy occurs.

In the early days of the internet, most people were amazed at how it empowered employment. However, the main reason retail users were attracted to the internet was not the promise of jobs but the possibilities of entertainment and socializing. Meme assets are akin to the entertainment industry in the cryptocurrency era, but due to associated losses, they struggle to generate the Lindy effect. Perhaps not everything should be transactional.

The fact is that only about 1% of internet users publish content. If we draw a parallel with cryptocurrency, there may exist a world where users do not engage in transactions 99% of the time they use an app. Finding ways to bring users together without making transactions the core value proposition is the magic of the next generation of consumer applications.

I know this sounds ironic. On one hand, I believe blockchain is a track for funds, and everything is a market. But on the other hand, I also acknowledge that keeping users trading can lead to user attrition. As people often say, attention is all you need.

So, what might this look like?

Here are some early observations from the social networking and entertainment fields.

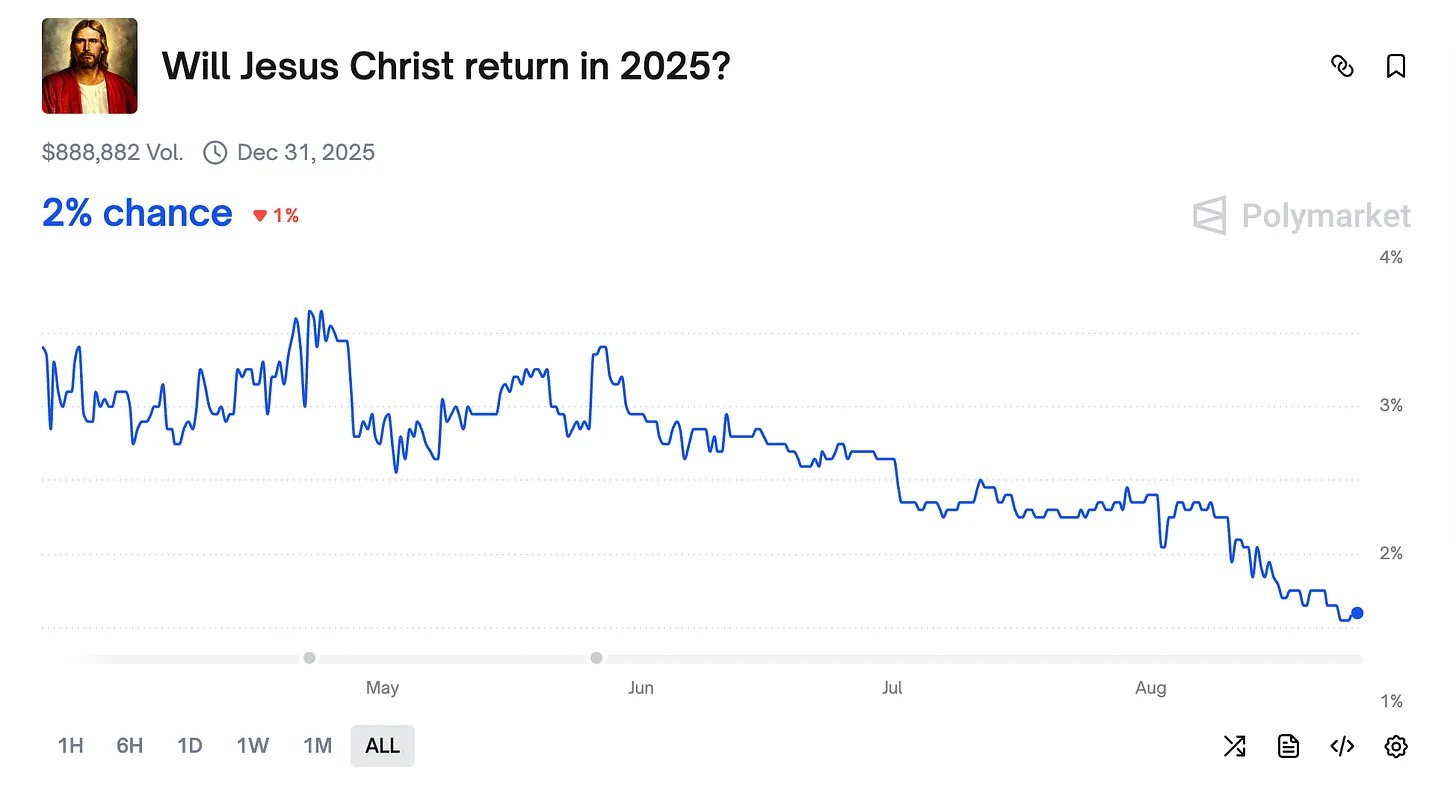

- Social networks built around prediction markets

Currently, prediction markets have reached out to large creators, suggesting they embed prediction markets into their content and earn a share of the transaction fees. For example, Twitter is about to integrate Polymarket into its feed. This model of merging attention and transaction economies will be supported by crypto tracks.

- Music streaming platforms with better unit economics

Currently, Spotify pays about $0.03 to $0.005 per play, partly because revenue is closely tied to lowering subscription costs. Allowing creators to issue digital collectibles and earn from them could be a way to increase this number. For example, I would love to own a signed digital version of Fort Minor's album "The Rising Tied."

Perhaps, in the future, there will be a world where vinyl records are issued on-chain but can be redeemed off-chain afterward. Such business models have already emerged sporadically. You can buy game card packs from Courtyard, but their social or streaming elements are isolated from each other.

This does not mean that financial jargon is unimportant. There is a reason we have been discussing Hyperliquid, Jupiter, and similar revenue-generating applications. They are the modern-day Medici Bank. The concentration of capital allows us to experiment with new tools for attracting attention. But maintaining attention lies in creating products that keep people coming back for non-betting reasons. Transactions need to evolve beyond mere speculation.

All of this makes me ponder—what is culture, really?

It is a collection of stories we cherish, the Pakistani songs exchanged with taxi drivers on the way home from work, the Kheer recipe I saved on Instagram. When someone asks about Bollywood movies, I recommend "Jab We Met," "Veer Zaara," or "Laapatha Las," because I believe they represent culture well. Or perhaps it is the church my family has attended for three generations, where I want to pray simply because a relative has not been diagnosed with an illness.

None of these situations involve monetary transactions. But there exists a foundation defined by shared stories and emotions that binds us together. There is a sense of belonging that makes things priceless. They are all momentary expressions that give life value, at the core of my identity. Momentary expressions add density to the rest of life. Somehow, the same emotions are also reflected in products.

After observing Apple’s products for a long time, you can trace elements back to Jobs' time at Disney. Picking up an iPhone, you can feel his desire to create beautiful things. It is these little details that make you buy iOS products year after year, even when the changes are minimal.

Web3 products rarely replicate this foundation on a large scale. In Web2, this was intentionally constructed. For example, Facebook did not launch with a points program; it focused on Ivy League graduates as its foundation. Quora was once the best place to gain insights from Silicon Valley developers. Substack remains the best place on the web to find literary works.

Web3 products have their own foundations. Observing the information flow of Pump.Fun or the discussions on Polymarket for a long time, you will see a new culture forming, but like any industry in its infancy, it struggles to sustain itself.

Remember when I said the internet turned love letters into effortless short messages? The internet has disrupted how people seek love. As of 2023, 40% of couples meet online. Ironically, this shows me how technology operates: on one hand, it changes the medium through which we express ourselves; on the other hand, it increases the surface area of randomness, allowing beautiful things to happen.

By clinging to the notion that "cryptocurrency is just a speculative application," we abandon the potential surface area of randomness that may exist. Perhaps it is time to view cryptocurrency as a medium of expression. Perhaps we should contemplate an alternative culture for an industry to which we have devoted so much of our lives. Let’s brew a renaissance!

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。