Cryptocurrency is a culture and a medium of expression.

Written by: Joel John

Translated by: Chopper, Foresight News

I often wonder what Michelangelo was thinking when he painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling. This work is considered one of the greatest artistic treasures in human history. But initially, he did not want to take on this task at all. Michelangelo's artistic domain was marble sculpture, with hammers, stone, and human forms being where he showcased his talent.

When he received the commission, he was deeply in debt due to an unfinished sculpture for the tomb of the late Pope. Pope Julius II asked him to paint the chapel's frescoes. Michelangelo felt it was a scheme by his rivals to make him look foolish, as the project was extremely challenging. He found himself in a dilemma: on one hand, there was the unfinished commission from the late pope, and on the other, the new task from the current pope.

I think that in those days, no one dared to stand before the leader of the Catholic Church and say "no." So he accepted the commission and spent four years from 1508 to 1512 painting the ceiling. He loathed the task so much that he even wrote a poem comparing himself to a curled-up cat. A few lines from the poem always resonate with me:

My painting has lost its vitality. Giovanni, help me guard it, maintain my dignity. I do not belong here — I am not a painter.

Did you notice the "Giovanni" mentioned in the poem? He refers to Giovanni di Giovanni da Pistoia. But there is another Giovanni relevant to us, Giovanni de' Medici. He was Michelangelo's childhood friend, and they grew up together. As a young man, Michelangelo was brought to the Medici Riccardi Palace with the support of Lorenzo de' Medici.

The Medici family was a prominent banking dynasty in medieval Europe. In modern terms, they would be comparable to JPMorgan or SoftBank. But they were also the financial architects of the Renaissance — the "godfathers" of this transformation.

520 years have passed since Michelangelo completed the ceiling, and I am still writing about him, partly because some of the most renowned bankers of that time supported him behind the scenes. Throughout history, capital has always intertwined with art, jointly creating what we call "culture." Most artistic works praised by society have substantial capital backing them. Michelangelo may not have been the top artist of his time.

Thinking about how modern media operates makes it even more interesting. Today's "Sistine Chapel" is not in Europe but on the internet. When you log into X, Instagram, or Substack every day, you are stepping into them. Today's "Michelangelo" does not have to wait for the favor of the Medici family, but they do hope the algorithms favor them. Modern "Medici" buy "churches" and then stamp their own marks on them. After Elon Musk acquired X, the views on his posts significantly increased within months. New "deities" are building their own "churches."

Technology can accelerate the pace of cultural change. In this era of 9-second short videos, memes are the "LEGO bricks" of culture, but they also require capital to scale. Without billions of dollars in funding and without relevant regulations protecting founders from imprisonment due to content on platforms, platforms like Facebook might not even be discussed.

Today, technology is the lever that changes culture because it expands the range of human self-expression. All technologies leave a cultural imprint because they change the medium through which people express themselves.

I have been pondering how technology, culture, and capital have intertwined over time. Once a technology scales, it attracts capital. In this process, technology converges its modes of expression. For example, in the crypto space, we no longer advocate radical decentralization but begin to discuss better unit economics; we no longer label banks as "evil," but praise how they distribute digital assets. This shift intrigues me, as it influences everything from founders' fundraising pitches to the storytelling of CMOs.

But before delving deeper, let's quickly outline the evolution of media itself.

Evolution

Humans are expressive "machines." From the moment we learned to use the juice squeezed from leaves to doodle in caves, we have been leaving traces of what we want to express: about animals, deities, lovers, about desire and despair. Once the medium of expression formed a network, our expressions became more vivid.

You may not have noticed, but our logo is a manual printing press. This is a tribute to Gutenberg and also carries a satirical meaning about information dissemination. At the end of the 15th century, when Gutenberg printed the Bible, he probably could not have imagined how his invention would promote the spread of information.

For instance, by the 17th century, almanacs (or dense scientific literature) became the primary form of reading material for Europeans. The ability to print and disseminate ideas, to some extent, propelled the scientific revolution. You could say "the Earth is not the center of the universe" without risking your life.

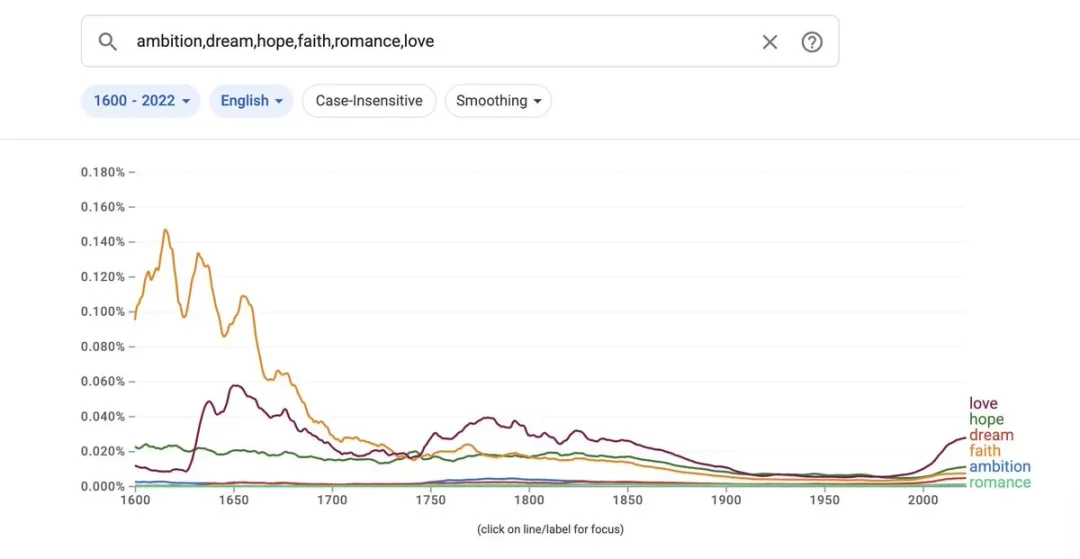

From the word frequency chart above, we can see that mentions of "faith" in literature have decreased, replaced by "love." Of course, I am not saying that all of Europe abandoned religion in search of better partners, but the essence of the medium has indeed changed. The tools that initially spread faith (the printing press) may have inadvertently contributed to the decline of faith.

The example of the printing press illustrates that once an information tool or technology is put to use and released, its uses can be foreseen.

It transformed the medium of written text from a "public good" to a "private good." Around the 18th century, people no longer read aloud but began to read in the quiet of their bedrooms, a trend that became increasingly common. This makes logical sense; before the proliferation of printed media, books and literacy were not common.

So at that time, reading was a social activity where people gathered together, and one person would read aloud. As book prices fell and the nobility had more leisure time, silent reading began to spread. At that time, people lost control over the ideas disseminated through books, leading to moral panic.

Families worried that teenagers were spending their free time reading love stories instead of participating in the industrial revolution. Clearly, the medium shifted from public affairs to private matters, from temple sculptures and monasteries to printed pamphlets in private hands. This changed the nature of the ideas being disseminated: from highly religious to scientific, romantic, and political. And these areas had no means of private dissemination before the advent of printed media.

The church, kings, and nobles had no reason to publish papers on the workings of power.

This may have contributed to the political upheaval at the end of the 18th century when both France and America felt it was time to change their governance. Let's not get lost in the details; there is still a century of media development to discuss, including radio, television, and the remarkable internet!

In the next century, profit models would change the way media operated. Media like radio and television relied on as many people as possible listening or watching at the same time. This meant that they could not focus on niche segments. Prime-time television programs were almost always news broadcasts rather than sizzling romance dramas, as those were the content the whole family would watch together.

The perspective of dissemination almost always aligned with the societal acceptance of the time.

Excerpt from Ben Thompson's article

Ben Thompson captured this shift brilliantly in his article "Never-Ending Niches." In the 1960s, I might not have had the channels to write about emerging technologies or find enough online readers. As a creator, I could only focus on content relevant to my local area. The internet changed that, allowing me to find people globally interested in the digital economy. Our readers come from 162 countries.

This is entirely thanks to the power of the internet. This scale also affects the way culture is disseminated.

J.K. Rowling's "Harry Potter," Jay-Z's "Blueprint" album, and Dr. Dre's headphones all share a commonality: they are outstanding works of art but become centers of capital due to their increased visibility. In this process, they form a flywheel where capital helps disseminate art, and art continuously appreciates capital.

But there is a common element behind these transformations, and that is technology.

Platforms like YouTube, Kindle, and Apple Music have spread their works to global audiences. Culture is no longer centered around the cities they are in but is consumed and recognized by international audiences. This greatly expands their audience reach, thereby improving unit economics. In turn, platforms also benefit from the users of these products.

When you want to attract a large number of users to a product, a shared culture is the easiest entry point. I previously wrote about how SuperGaming leveraged well-known brand IPs to promote games, and to date, their downloads have exceeded 200 million.

Excerpt from the Financial Times

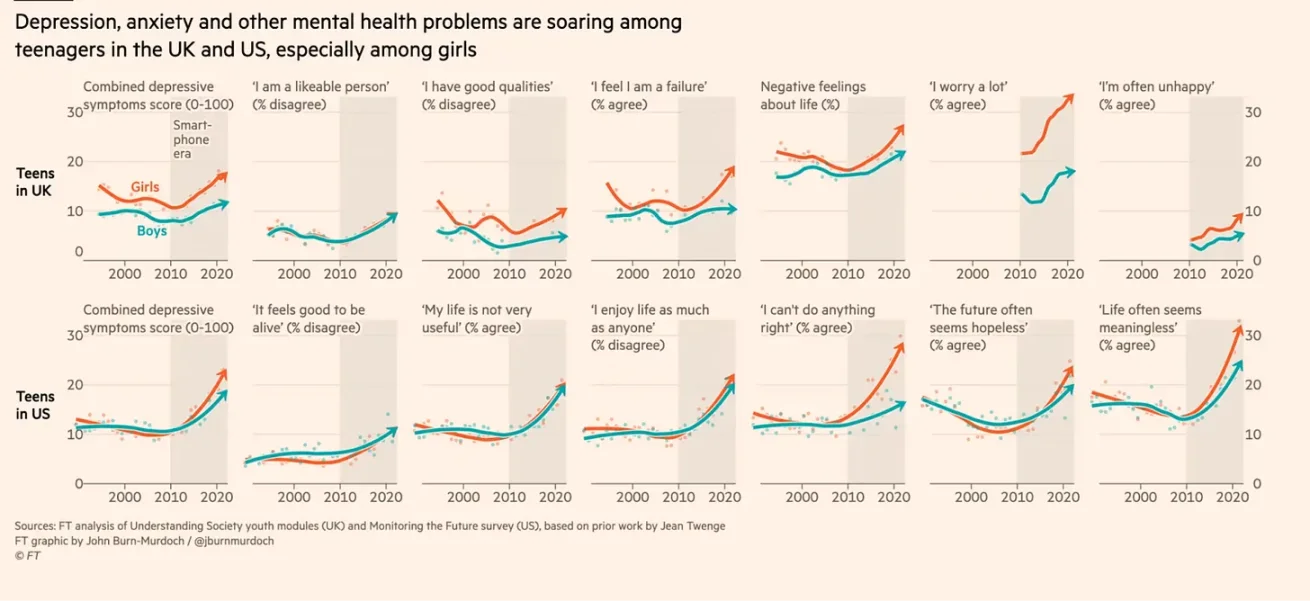

In the age of artificial intelligence and algorithmic recommendations, culture often tends to centralize. Today's youth do not have to struggle to find new media; they may find themselves caught in a vortex of content that continuously reinforces their worldview. Large language models (LLMs) exacerbate this risk, as people see not human-created content but engage in conversations with chatbots that reinforce existing viewpoints. This can lead to dire consequences, including suicide. But on the other hand, the same tools are increasingly used for psychological therapy.

This is the duality of technologies like the internet: on one hand, it is the best place for a boy from a small town in India to discover top artists and aspire to become one of them; on the other hand, it is also the best place for people to find terrible viewpoints and get caught in a vortex of content that continuously reinforces those viewpoints. This also explains why society seems increasingly divided: we have no dialogue, only algorithmic reinforcement.

We have lost legends, only content remains; for the sake of viral dissemination in niche areas, depth has been sacrificed. If it brings clicks, what does truth matter?

When everyone has only 15 seconds of fame, we sacrifice the nuances of storytelling for catchy melodies and dazzling moments. Those timeless stories, emotions, and virtues are compressed into quick dopamine hits during meeting breaks. The human experience has turned into a screen that you swipe through, like pulling levers in a modern casino, just to find content that resonates.

What does this have to do with cryptocurrency? To understand this, we need to look at how this industry has evolved.

Transformation

From Michelangelo to Jay-Z, from the Medici family to SoftBank, it is evident that capital helps culture scale. When a culture is linked to monetary stability, more people will accept it. Technologies like the printing press, broadcasting, and the internet facilitate the dissemination of culture. Creating art requires capital, and the means to spread art also requires capital.

But what happens when the medium of expression itself is currency? This is the trillion-dollar question that the cryptocurrency industry attempts to answer.

The initial intent of cryptocurrency was to replace banks with the values of cypherpunks. It makes sense; many people on the mailing list where Satoshi Nakamoto sent the Bitcoin white paper had encountered trouble due to their work in cryptography. In the early 1990s, exporting encryption software was akin to exporting nuclear weapons. So you can understand why early adopters had a deep-seated suspicion and aversion to the government.

The early adopters of Bitcoin were not fintech enthusiasts but rather drug markets like "Silk Road" and institutions like WikiLeaks that had been deprived of banking services. In 2011, when WikiLeaks adopted Bitcoin after being cut off by PayPal, Satoshi Nakamoto remarked that they had "stirred up a hornet's nest." At that time, Bitcoin was still on the fringes. The ICO of Ethereum in 2014 brought attention to the industry.

Uber? On-chain. Tinder? Also on-chain. Your local government? It has to go on-chain too!

We want to put everything on-chain and tokenize it because the world needs more decentralization. Just kidding.

Two factors played a role here:

First, Ethereum's smart contracts made the issuance, transfer, and trading of assets easier;

Second, on-chain financing was a novel idea, allowing founders to bypass "evil" venture capital and raise funds from the community.

ICOs provided liquidity for venture capital equity investments and allowed retail investors to participate. The optimistic vision at that time was that the venture capital business model would be disrupted. The culture of that era revolved around how shared ownership of assets and distributed governance could lead to better outcomes.

Like many chapters in financial markets, that period was filled with vibrant optimism until asset prices fell.

As the market evolved, the cryptocurrency space differentiated into two types of users: one type is quantitative traders, and the other is "farmers."

Quantitative traders are mostly seasoned traders who accumulate wealth using capital pools, information channels, and a comprehensive understanding of finance.

"Farmers" are ordinary users in the crypto space who contribute raw labor to protocols. I consider myself a "farmer" because most of my crypto assets come from labor contributed to protocols. The long-tail group of "farmers" consists of users willing to put in extra effort for airdrops.

You don't even need to issue tokens; you can just call them "points" and paint a vision.

As the cold and brutal bear market arrived, we shifted from "wanting to overthrow the government" to "looking forward to airdrop subsidies."

Suddenly, the focus was no longer on decentralization but on which tokens might be considered the most valuable. This mirrors the evolution of media, as I mentioned earlier, shifting from private consumption media to social reputation media. By 2019, with the ICO boom fading, no one could raise funds solely by issuing tokens anymore.

But the signaling mechanism changed. The market began to price tokens based on "which venture capital invested" and "which exchange they might list on."

Like any nascent industry, we were fumbling to find our voice. Should I call everyone "sir"? Should I really attend DAO meetings? Who cares?

We mistook a large group of members in our Discord chat for a "community," believing that tokens were the product and that token prices were indicators of product-market fit. We overlooked the fact that protocols valued in the billions often earn less than $100 a day. We equated the founders' ability to discuss issues with their ability to execute. Most importantly, we treated technical jargon as a sign of novelty and capability.

When Bitcoin surged after the ETF hype while most altcoins lagged behind, we woke up to the realization that "the emperor has no clothes."

The revival of meme coins in 2024 symbolizes the market's recognition that "volatility itself is the product." As long as prices rise and asset issuance appears fair, people will come to trade. From WIF, Fartcoin, to various meaningless assets, we realized that sometimes speculative assets can also serve as a medium of expression. The common sentiment conveyed by all these assets is a thirst for profit.

Crypto culture shifted from being centered around ideology or technology to focusing on the behaviors it unlocks, with the spotlight now on trading. This makes sense: if the blockchain is a conduit for funds, its core purpose should be to transfer funds quickly and efficiently. However, in this process, different choices emerged, indicating that a parallel culture is forming within the crypto space.

Most scalable products touch upon behaviors that may seem strange to outsiders. Layer3 can easily be mistaken for a platform for airdrop "farmers," but a closer look reveals that they have built a full-stack solution that allows millions of users to enter Web3. They provide on-chain reputation tools, wallets, and exchange functionalities, supporting the most chains. What might be perceived as a "task platform" product has now become an essential tool for early product growth.

Who could have predicted this back in 2021?

Similarly, NFTs were once considered outdated technology, but Pudgy Penguins proved otherwise. They partnered with Walmart to generate over $10 million in revenue. The brand's assets garnered nearly 120 billion views, with about 300 million views daily. Pudgy utilized crypto-native technology but made it meaningful in a completely different way — by collaborating with retail stores and leveraging Web2 social networks for attention.

Both products raise questions: what is crypto culture? Is it blind speculation on memes? Is it getting liquidated daily on perpetual contract exchanges? Or is it betting everything on a token issued last night simply because we believe AI will disrupt jobs, and we have less than two years to escape the "permanent middle class"?

The market has given us the answer: cryptocurrency is both a medium of expression and a trading culture. Consumers have accepted its ability to transfer value reliably, which is why stablecoins have become the primary mechanism for global fund transfers. But at the same time, they have rejected other ideas, such as "play-to-earn," which ended in failure. Although I wish it could succeed, content tokens are currently not making much progress.

I see my friends sharing content on Instagram every day, yet I have no idea how much my content on Zora is worth, which is quite sad.

Just as there is no freedom of speech without some offensive remarks, it is difficult to achieve global resource coordination without bad actors exploiting the market. In both cases, actions have consequences. If you do poorly for a long time, no one will listen to you anymore, and no one will buy the assets you issue. Ironically, crypto Twitter may be facing both consequences simultaneously.

It must be acknowledged that the trajectory of cryptocurrency evolution is similar to that of most media. We do not know how many thousands of books have become irrelevant, and the internet is filled with millions of blogs that no one knows or cares about. Social media operates because the content people post becomes outdated within a day. Crypto assets will be the same; currently, there are over 40 million tokens, many of which will ultimately go to zero. Perhaps one day, people will nostalgically remember content tokens, just as they recall NFTs from 2021 or ICO tokens from 2017.

For most things, irrelevance is the norm unless there is culture involved.

The definition of culture often lies in its mode of communication. Language determines how we feel and understand the world around us. Before 2021, it was fine to speak in jargon, but when we need to break out of this core niche, we must use less jargon and speak in ways that people can understand.

For example, your dating app cannot just say it uses zero-knowledge proof technology; people just want dating opportunities. The competitive edge of stablecoins is not in how many networks they support; people will choose the global transfer method that is the cheapest and fastest. Consumers care about what they can get right now, not the "layered vision" that may be realized in the future.

The closer our industry gets to consumer products, the more we need to speak in a language that ordinary internet users can understand. And because language is often determined by the environment and frequency of interaction, we need to change how we guide and retain these consumers.

The "Medici family" of this new era will be the masters of attention. Ironically, the "Michelangelo" of the new era will be the artists defining the flow of capital.

Absolution

One way to think about cryptocurrency is to understand it through the lens of casinos and the coffee shop near your home. The circulation of money in casinos is indeed fast; people frequently transfer funds on casino products, but casinos are often the winners. You won't see people "settling" in casinos for long, at least not most people. In contrast, community coffee shops can attract foot traffic every day.

It is usually the same group of people gathering under the pretext of having coffee, sharing stories and worries. It is the calm and pleasure brought by that space that attracts them back time and again. In more religious societies, temples or churches play a similar role. Coffee or faith becomes the "substrate" that binds people together, but the reasons people stay go far beyond this foundational product itself.

Culture is a collection of stories that people share with one another. The stories we share today are often price charts; when the charts turn green, people have little reason to return. How do we keep people engaged? Is there a way to bridge the gap for this technology?

To understand this, perhaps we should look at the internet itself. Two forces are shaping the internet:

First, in the era of AI and large language models, vast amounts of content are being created. When everyone is a creator, no one can truly be a "creator." People need mechanisms to own, monetize, and distribute their content.

Second, verifiability. In attention economies like X or Instagram, a massive amount of AI-generated "dross" can keep people engaged longer; the more eyeballs, the more clicks, the more money.

What cryptocurrency can do for the internet ultimately relates to verifiability and ownership. These ideas are not new; we have discussed them in this publication since 2023. However, changes in regulation and shifts in the attitudes of capital allocators are the main reasons to seize these opportunities now.

The internet has always been a tool for free expression, and cryptocurrency enables people to own the channels and networks that create these expressions, allowing assets to be freely issued, traded, and held. When everyone can express themselves through currency, the meme coin craze emerges.

When the internet emerged, most people marveled at how it would change work, but what attracted ordinary users to go online was not job prospects, but the possibilities of entertainment and socializing. Meme assets are akin to entertainment in the crypto era, but due to accompanying losses, it is difficult to have a "Lindy effect." Perhaps not everything should be a trade.

Only about 1% of people on the internet publish content. Analogously, in the crypto space, there may exist a world where users do not need to trade 99% of the time in applications. The magic of the next generation of consumer applications lies in finding ways to engage users without making "trading" the core value proposition.

I know this sounds ironic. On one hand, we say that blockchain is a conduit for funds and that everything is a market; on the other hand, we acknowledge that keeping users trading will lead to attrition. As people often say, attention is all you need.

So how exactly should this be done?

We can see some early signs from social networks and the entertainment sector:

Social Networks Built Around Prediction Markets

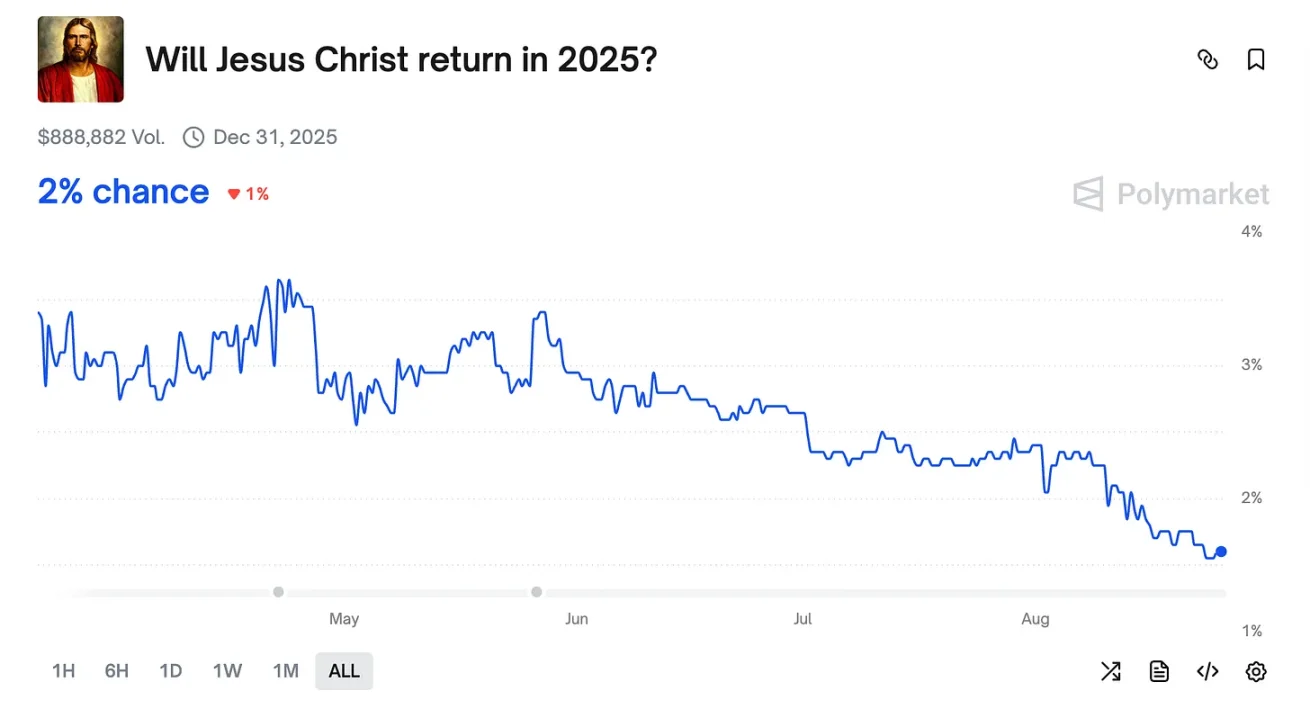

Currently, prediction markets have begun to engage large creators, suggesting embedding prediction markets within content to direct some trading fees to creators. Twitter is set to integrate Polymarket into its feed. This model of merging attention with trading economics will be supported by crypto channels.

Music Streaming Platforms with Better Unit Economics

Today, Spotify pays about $0.005 to $0.03 per song play, partly because revenue is needed to maintain low subscription fees. Allowing creators to issue digital memorabilia and share in the profits might improve this figure. For instance, I would love to own a signed vinyl record of Fort Minor's "Rising Tied."

There may exist a model where vinyl records are issued on-chain and can later be redeemed offline. This business model has appeared in certain areas: you can buy game card packs from Courtyard, but the social or streaming elements are isolated.

This is not to say that financial foundational tools are unimportant. There is a reason we keep discussing revenue-generating applications like Hyperliquid and Jupiter; they are like the modern "Medici Bank." Concentration of capital allows for the experimentation of new tools, thereby gaining attention.

But for sustainable development, we need to create products that people are willing to return to without "betting." Trading needs to transcend mere speculation.

All of this makes me ponder: what exactly is culture?

It is those shared stories we cherish: exchanging Pakistani songs with a taxi driver on the way home from work; saving a Kheer dessert recipe on Instagram just because a loved one said her mother would make it for her when she was sick; recommending "Jab We Met," "Veer Zaara," or "Laapatha Ladies" when someone asks about Bollywood movies because I feel they represent that culture well.

None of these scenarios involve monetary transactions, but there is a "substrate" formed by shared stories and emotions that binds us together, and that sense of belonging makes things priceless. They are fleeting expressions that give life value and are at the core of my identity. These transient expressions add depth to other parts of life, and this emotion is reflected in products.

Staring at Apple products for long, one can trace back to the shadow of Steve Jobs during his time at Disney; picking up an iPhone, one can feel his desire to "create good products." It is these details that make you buy iOS products year after year, even if the changes are minimal.

Web3 products rarely scale to replicate this "substrate." Web2 products are intentionally crafted: for example, when Facebook launched, there was no points program; instead, it focused on the "substrate" of Ivy League graduates; Quora was once the best place to gain insights from Silicon Valley developers; Substack remains a great place to find quality content online. Web3 products also have their own "substrate."

If you stare at the feed of Pump.fun for long or look at the discussions on Polymarket, you can see a new culture forming, but like any nascent field, it is still struggling to take root.

Remember when I said the internet turned love letters into effortless texts? The internet has also disrupted how people find love — in 2023, 40% of couples met online. Ironically, this illustrates the role of technology: on one hand, it changes the medium through which we express ourselves; on the other hand, it expands the possibilities for beautiful things to happen randomly.

If we cling to the notion that "cryptocurrency is only related to speculative applications," we will miss out on those potentially random beauties.

Perhaps it is time to view cryptocurrency as a medium of expression, and perhaps it is time to think about a new culture for the industry we are in.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。