Author: Lawyer Liu Zhengyao

Introduction: The Importance of Civil Judgments Involving Virtual Currency Under Regulatory Storms

On September 24, 2021, the People's Bank of China, along with ten ministries including the "Two Highs and One Department," jointly issued the "Notice on Further Preventing and Dealing with Risks of Virtual Currency Trading and Speculation" (hereinafter referred to as "9.24 Notice"), marking the beginning of comprehensive regulation of virtual currency-related business activities in mainland China. Recently, regulatory authorities and industry associations have issued documents reiterating the strict enforcement of the "9.24 Notice" and clarifying that the regulatory stance on virtual currencies has escalated to "comprehensive prohibition." Legally speaking, any business activity involving virtual currencies is considered illegal financial activity, and trading in virtual currencies is neither encouraged nor supported.

However, there often exists a gap between the prohibitive legal provisions and the objective needs of society. Despite the looming regulatory sword, virtual currencies, as a form of "digital asset" with significant market influence globally, have not seen a decrease in civil legal disputes; rather, they have become increasingly complex and acute due to the "underground" nature of trading and the emergence of risks.

In recent years, the number of civil cases involving virtual currencies accepted and adjudicated by the people's courts has shown a significant upward trend, with the legal relationships involved extending from traditional property disputes and contract disputes to new areas such as entrusted investment and technical services.

In this context, the author conducts a systematic analysis of the judgment standards and judicial attitudes of mainland courts regarding civil disputes involving virtual currencies, aiming to provide reference for all parties involved.

I. Why Study the Judgment Standards for Virtual Currency Cases?

First, it concerns the protection of personal property rights. Although virtual currencies do not have the same legal status as fiat currencies and should not be circulated or used as such in the market, does virtual currency, as a "specific virtual commodity" or "data rights," still possess property attributes in the civil domain? How should the real money invested by parties be classified? This is a challenge that courts must face.

Second, it concerns the balance of market order. Court judgments must not only enforce regulatory policies and declare the validity of contracts involving virtual currencies but also avoid causing significant property losses to parties due to "invalid contracts," preventing the formation of a negative trend of "bad money driving out good" or even "unearned gains."

Third, it concerns the unity of the judiciary. It is well known that there are currently no specific laws and regulations regarding virtual currencies in China. In the absence of clear higher laws, different courts may reach completely different judgments when handling similar cases (same case, different judgments), and the uniformity of judgment standards urgently needs to be established.

Therefore, an in-depth analysis of existing civil cases involving virtual currencies, summarizing their judgment logic and extracting core viewpoints, is not only a necessity for legal practice but also a profound exploration by the author of the subtle balance between "regulatory documents" and "private law autonomy."

II. What Types of Civil Cases Involve Virtual Currencies?

(1) Virtual Currency Investment Disputes

This is the most common type, with the core dispute revolving around the validity of entrusted investment agreements. Investors hand over funds or virtual currencies to trustees, entrusting them to conduct virtual currency trading (such as contracts, spot trading) to obtain profits, but ultimately incur losses, leading to litigation. Courts generally consider two factors:

First, the validity of the contract: Courts typically cite the "9.24 Notice," determining that contracts for investing in virtual currencies or providing related services are invalid due to violations of mandatory provisions (such as disrupting financial order); Second, loss sharing: After a contract is deemed invalid, the return of the principal is the basic principle. However, regarding the losses incurred, courts will consider whether both parties have fault. If the principal was aware of the national prohibition but still participated in the investment, they bear significant fault; if the trustee provided professional services or acted as an intermediary, their fault is greater. In practice, it is common to share responsibility or have the trustee bear the main responsibility.

(2) Virtual Currency Lending Disputes

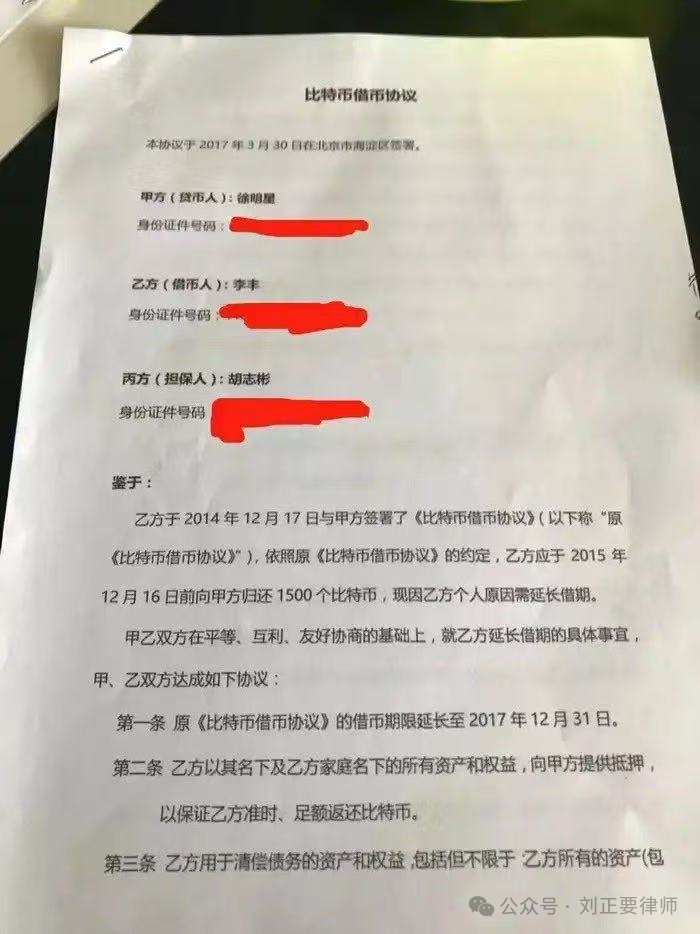

These cases involve virtual currencies as the subject of lending, typically involving lenders lending a specific amount of Bitcoin, Ethereum, etc., to borrowers, with an agreement to return the amount or its equivalent in RMB upon maturity. Recently, it has circulated online that Xu Mingxing, the owner of OKEx, lent out 1,500 BTC, which the other party failed to return by the due date, and Xu has yet to achieve a resolution.

(Image source: Internet, will be deleted upon request)

Courts mainly consider two aspects: first, the validity of the loan contract. According to current policies, courts will determine that virtual currencies do not possess monetary attributes, thus not constituting traditional financial loan contracts. If virtual currencies are viewed as general property or objects, they constitute a loan contract, which is not necessarily invalid. At this point, the second issue to consider is: the method of return and conversion. If the court recognizes the validity of the loan contract, the focus of the dispute shifts to how to return. Is it the original currency returned, or is it converted to RMB? If converted, should the conversion be based on the date of borrowing, maturity date, or date of judgment? In practice, most tend to determine this based on the purpose of the loan or the true intentions of the parties, and courts generally do not actively convert the disputed virtual currency into legal currency (this essentially constitutes a pricing of virtual currency, which does not comply with the provisions of the "9.24 Notice").

(3) Virtual Currency Mining Disputes

"Mining," as a high-energy-consuming activity, has been explicitly prohibited. Disputes arising from this mainly revolve around the sale, leasing, custody services of mining machines, power supply, and related operational management and technical development. Common disputes in practice include mining machine sales contracts, mining site leasing/custody contracts, and power procurement contract disputes. According to Article 85 of the 2023 "National Court Financial Trial Work Conference Summary (Draft for Comments)," when courts hear such cases, they will examine the contract signing date. If the contract was signed before September 3, 2021 (the date when regulatory authorities issued the "Notice on Rectifying Virtual Currency 'Mining' Activities"), the state had not explicitly prohibited virtual currency mining, and the contract is generally valid; contracts signed after September 3, 2021, will be deemed invalid by the court.

Consequences of Handling: After a contract is declared invalid, courts typically rule to terminate the contract, and mining equipment can be returned (without considering administrative regulation). However, for already performed power supply and custody service fees, courts generally will consider the principles of "unjust enrichment" or "property handling of invalid contracts," taking into account the fault of both parties to decide whether to support payment or return.

(4) Virtual Currency Property Infringement and Unjust Enrichment Disputes

These involve virtual currencies being stolen, scammed, or mistakenly transferred, falling under non-contractual debts. Common forms in practice include victims encountering theft of virtual currencies or fraud; or mistakenly transferring to others due to operational errors. From the perspective of civil law (i.e., not considering criminal reports), there are two main factors: first, the confirmation of property attributes. In the fields of infringement and unjust enrichment, theoretically, courts are more inclined to recognize virtual currencies as a form of network virtual property, thereby supporting the right to return of victims or payers. In practice, many courts are reluctant to accept such cases, either directing parties to pursue criminal charges or refusing to accept the case on the grounds that "virtual currencies are not protected by the state"; second, the performance of return. Even if the aforementioned rights are confirmed, due to the anonymity, transnational nature, and price volatility of virtual currency transfers, how to enforce and return remains a challenge in judicial practice.

III. Summary of Main Viewpoints in Existing Judgments

Through a systematic review of hundreds of civil judgment documents involving virtual currencies in recent years, the mainland courts have gradually formed some core viewpoints and judgment tendencies that are becoming unified when handling such cases.

(1) Determination of the Validity of Contracts Involving Virtual Currencies: Based on "Regulatory Prohibition"

Currently, when courts determine the validity of contracts involving virtual currency transactions, they almost uniformly take national regulatory policies as the highest guideline, especially the "9.24 Notice," which specifically includes the following aspects:

First, negative determination. Any contract that directly uses virtual currency as the subject of the transaction or directly provides services for virtual currency trading (such as entrusted trading, virtual currency exchange, mining machine custody, etc.) is typically deemed by the court to harm social public interests and disrupt financial order, and the contract is declared invalid.

Second, limited support. For legal relationships that do not have trading as the direct purpose but regard virtual currencies as general property or data rights (such as infringement, unjust enrichment, and some courts' recognition of loan contracts), courts may, to a limited extent, acknowledge the property attributes of virtual currencies at a level that does not involve financial order, thereby protecting the parties' right to request the return of property.

(2) Property Handling After Contract Invalidity: Fault and Return Principles

After a contract is declared invalid, the return of property and the sharing of losses become the focus of judgment, directly reflecting the "temperature" and "balance" of the judiciary. Generally, it involves the following aspects:

First, return of the principal. For the RMB principal invested in entrusted investments or loans, courts generally support its return. This is based on the principle of mutual return after contract invalidity, but the degree of "fault" of both parties will be considered, making it difficult to fully support one party.

Second, consideration of "fault" in loss sharing. Both parties' faults: Courts will clearly point out that the investment risks of virtual currencies and regulatory policies are a social consensus; therefore, the principal (investor) bears significant fault for participating in the investment despite knowing the risks. Trustee's fault: The trustee (platform, operator) is usually deemed to have greater fault due to organizing, planning, or providing professional services, especially in cases involving fraud or professional advantage.

Third, judgment results. The final judgment results often reflect both parties sharing losses according to their fault ratio, or the trustee with greater fault bearing all or most of the return/compensation responsibility. For example, in cases of invalid mining contracts, courts typically rule that mining equipment can be returned, but for the consideration of services already performed (such as electricity fees, custody fees), the decision on whether to support payment must be made based on the fault ratio.

(3) Disputes Over "Conversion Benchmark Date" in Lending Cases

In a few cases where virtual currency lending is recognized as a valid "loan contract" or requires property conversion, determining the benchmark date for currency conversion is key. Courts have three main principles when ruling:

First, on mainstream value tendencies, considering the severe price volatility of virtual currencies, most courts tend to choose the date when the obligation arises (such as the agreed repayment date or borrowing date) as the conversion benchmark date; Second, to avoid "speculation." Few courts choose the date of judgment for conversion, as this may lead to the winning party obtaining significant speculative gains or the losing party bearing losses beyond their expectations, violating the principle of fairness. The court's goal is to restore the state before the contract was invalid, not to support one party's speculative interests; Finally, and most importantly, the court does not price virtual currencies. The premise for the aforementioned virtual currency value conversion is that the contracting parties must agree on the value (price) of the virtual currency themselves, and the court will respect the parties' autonomy. However, if the parties do not agree, the court will not and cannot actively determine the market value of the virtual currency.

IV. Conclusion: The Ban Cannot Stop the Tide, Future Civil Disputes Involving Virtual Currencies Are Promising

Currently, the regulatory policy in mainland China has drawn a clear red line regarding virtual currency trading speculation. From the perspective of current judgment standards, "comprehensive prohibition" is the core logic for determining the validity of contracts involving virtual currencies, with courts declaring contracts invalid to uphold the national financial regulatory order from a judicial standpoint.

However, we must recognize that virtual currencies, as a cross-border digital asset operating based on underlying technological logic, will only continue to enhance their influence and penetration globally. They have irreversibly integrated into the global economy and social life. There are two reasons for this:

First, the sources of civil disputes have not dried up. As long as virtual currencies still hold market value, the demand for investment, holding, and trading will not cease, leading to the continued existence of property relationships and creditor-debtor relationships between individuals.

Second, the challenges of new types of disputes are increasingly severe. With technological development, civil disputes involving new forms such as DeFi, NFT, DAO, and RWA will gradually enter the judicial spotlight, placing higher demands on the courts' expertise and judgment wisdom.

Therefore, the future of civil disputes involving virtual currencies will only increase, not decrease. While mainland courts adhere to the overarching principles of regulation, they must demonstrate stronger legal technicality and discretionary balance in individual cases. They must not only legally stop and punish behaviors that disrupt financial order but also strive to protect the legitimate property rights of parties through property return and unjust enrichment rules after a contract is declared invalid.

Ultimately, the evolution of judgment standards in civil cases involving virtual currencies will vividly reflect the continuous exploration and improvement of China's legal system in the era of the global digital economy, amidst the tension and even conflict between public law regulation and private law autonomy.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。