Author: Bennett Ma

In the face of the complexity of smart contract applications, we should abandon the simplistic thinking of "code is law" and instead adopt a more nuanced and pragmatic perspective of "contextual analysis." Only in this way can we clearly define rights and responsibilities, manage benefits and risks while embracing technological innovation.

Introduction

The concept of "Smart Contract" initially described merely a digital protocol capable of automatic execution. However, when the concept was put into practice, people discovered that this automatically running code could serve as rules for organizational governance, channels for asset transfer, and even tools for illegal activities, beyond just acting as a "contract."

Although smart contracts are not used as "contracts" in many scenarios, they are commonly referred to as "smart contracts." This indicates that "smart contract" is not a legal concept but a technical concept with different application scenarios. Different scenarios correspond to different social relationships, and different social relationships, once confirmed by law, become legal relationships. A slight change in the scenario may lead to different corresponding social and legal relationships.

Based on this, this article aims to explore the legal qualification issues of smart contracts in different application scenarios. While it may not cover all situations, it still hopes to help readers gain a basic understanding of the relevant legal issues.

Why Clarify the Legal Qualification of Smart Contracts? — Qualification Determines Fate

To understand the importance of clarifying the legal nature of smart contracts, one need only examine real judicial conflicts.

Tornado Cash is a decentralized, non-custodial mixing protocol deployed on Ethereum, centered around a series of immutable smart contracts. Users can deposit cryptocurrencies into a "liquidity pool" constructed by these contracts for mixing, thereby obscuring the source and destination of transactions.

Since its creation in 2019, the protocol has been used for money laundering exceeding $7 billion, leading the U.S. Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) to sanction Tornado Cash in August 2022 under an executive order. A key point to note is that the executive order stipulates that the targets of sanctions must be "property" owned or controlled by "legal entities."

Additionally, in August 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice also filed criminal charges against the co-founder of Tornado Cash, accusing the founder of conspiracy to commit money laundering, conspiracy to violate sanctions, and conspiracy to operate an unlicensed money transmission business.

These two actions point to several core legal controversies:

Is the "smart contract" itself a legal "entity," or is it merely "property," or just a "contract," or simply "code"?

Is the "smart contract" and the massive liquidity pool it manages, a "property" that can be sanctioned?

In terms of criminal liability, how should "smart contracts" be viewed, and how will their legal nature affect the legal responsibilities of the founders?

The outcome is:

In terms of sanctions, the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in November 2024 that OFAC's sanctions were overreaching. The court's core view is that "smart contracts" are merely "a neutral, autonomous technical tool" rather than a legal entity, and these "immutable smart contracts" cannot be owned or controlled by any individual or entity, nor can anyone prevent others from using them. Therefore, they do not meet the traditional legal definition of "property," and thus OFAC has no authority to list them as targets for sanctions.

However, in terms of developer liability, the victory of technology does not mean that developers can rest easy. Smart contracts are viewed as "the core tool and component of an unlicensed money transmission service," and the actions of the smart contracts along with the developers were classified as "operating an illegal financial business." Consequently, in the criminal trial at the end of 2024, founder Roman Storm was convicted of "operating an unlicensed money transmission business."

The Tornado Cash case clearly indicates that the legal qualification of smart contracts may directly determine the direction of the case and the fate of the parties involved. The code itself may be neutral, but the creation, deployment of the code, and the parties involved may need to be held accountable for the actual impacts and consequences it brings.

This enlightens us that a careful assessment of the legal nature of "smart contracts" in conjunction with specific scenarios is no longer optional but a necessary requirement to maintain transaction security and determine legal risks.

The Legal Nature of Smart Contracts — Context Determines Nature

The legal nature of smart contracts depends on the specific context in which they are deployed and operated.

Different contexts reflect or construct different social relationships, and the law evaluates them differently, thus corresponding to different rights, obligations, and responsibilities.

Below, I will present some typical application scenarios:

(1) The Legal Nature of Smart Contracts When Used to Construct Contracts

When discussing the legal nature of smart contracts, the most concerning question is often: Can it be recognized and enforced by law? Does it possess the legal effect of a contract?

When it comes to "contracts," many people first think of "consensus." Indeed, using smart contracts to trade digital collectibles is a form of consensus; participating in voting decisions in decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) is also a form of consensus. However, not all "consensus" can constitute a legally recognized "contract."

"Consensus" is a relatively broad concept, similar in meaning to "agreement," but they cannot be directly equated with "contract." From a legal perspective, a contract is a subordinate concept of "consensus" or "agreement," and the core feature of a contract is the guarantee of legal enforceability. While resolutions are also products of consensus, the law often only "confirms" their procedural validity and does not necessarily grant them enforceability.

In simple terms, we can use a streamlined judgment framework to determine whether a smart contract constitutes a "contract": Contract = Consensus + Legality

Consensus refers to the agreement of the parties' intentions, typically requiring both or multiple parties. The execution of smart contracts often reflects a pre-established common intention.

Legality encompasses two layers of meaning:

The law recognizes such consensus as a contract: Not all consensus is regarded as a contract. For example, internal resolutions executed via smart contracts are typically not classified as contracts but as organizational governance actions.

The content of the consensus does not violate laws and regulations: This includes not infringing specific prohibitive provisions (such as money laundering, fraud, concealment, etc., or financial regulatory policies) and not contravening legal principles such as public order and good morals. The former is relatively clear, while the latter requires specific analysis in conjunction with judicial practice and regional legal culture.

This framework can help us initially judge whether a specific smart contract application may be recognized as a contract and the source of its enforceability.

For example, we can apply this judgment method to analyze the following situations:

Situations that may constitute a contract:

Both parties enter into a digital collectible sales contract through digital signatures. If the intention genuinely reflects consensus and the content is legal, the smart contract may possess contractual effect.

On the basis of an existing written contract, new terms are supplemented in the form of a smart contract. If the terms themselves are legal, they can be regarded as part of the contract.

If the smart contract is merely used as a tool to fulfill existing contractual obligations, and it still reflects consensus and the content is legal, it may also be recognized as a contract (if it conflicts with a written contract, the priority of enforceability needs to be judged separately).

Situations that do not constitute a contract:

A single person using a mixer for money laundering lacks a counterpart, thus does not constitute "consensus."

Both parties use smart contracts for virtual currency transactions. If used for illegal activities such as money laundering or gambling, due to illegal content, it does not constitute a valid contract.

In a DAO, executing voting, profit distribution, and other governance actions through smart contracts is typically recognized as internal resolutions of the organization rather than contracts.

It is important to note that the legality of smart contracts and the legality of the virtual currencies involved are two different issues. Even if virtual currencies are recognized as having property attributes, if the smart contract violates public order and good morals or financial regulatory provisions, it may still be deemed invalid.

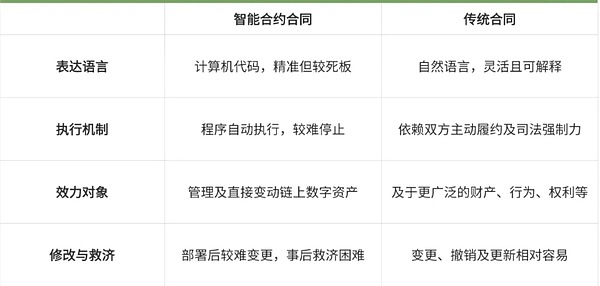

Furthermore, although some smart contracts may be recognized as contracts, they still possess a series of characteristics that differ from traditional contracts, such as:

These characteristics profoundly affect the rights, risks, and remedies of the parties involved.

For example, in the case of technical defects in smart contracts, the risk burden needs to be assessed in layers:

For both parties to the contract, risk allocation must comprehensively consider multiple factors, including the specific design of contract terms, the execution mechanism of the smart contract, each party's understanding of the relevant technology, the depth of participation in the process, and the due diligence obligations.

For the programmer, the key to determining liability usually lies in whether they provided services for compensation:

If the programmer acts as a third party providing paid services, their legal status can be likened to that of a product provider, and they must bear responsibility for code defects. However, the scope of liability should be limited to service fees or may extend to the transaction price involved in the contract; currently, judicial practice has not formed a unified standard.

If the code originates from an open-source project or is provided free of charge, the likelihood of the programmer bearing legal responsibility is relatively low.

(2) The Legal Nature of Smart Contracts When Used to Build Decentralized Autonomous Organizations

The application of smart contracts in decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) is very extensive, primarily functioning at three levels:

1. Defining organizational rules — stipulating governance mechanisms, member rights and responsibilities, and decision-making processes;

2. Forming collective resolutions — aggregating member will to make specific decisions;

3. Ensuring automatic execution — implementing rules and resolutions through code.

From the perspective of legal qualification, different functions correspond to different legal natures:

If the contract is primarily used to define organizational rules, it may be regarded as organizational bylaws, partnership agreements, or autonomous regulations, with its specific qualification depending on the content of the contract itself, which also shapes the legal attributes of the DAO.

If the contract is used to form collective resolutions, it is generally recognized as a resolution action, binding on the organization and relevant participating members.

If the contract merely serves as an automatic execution tool, it may not possess independent legal attributes but is viewed as a technical means to achieve organizational functions. Even so, it will still be subject to the constraints of laws, regulations, or internal agreements of the organization. For example, it must be consistent with existing bylaws, relevant functions should be disclosed, and execution errors may lead to liability for developers or members, among other considerations.

In practice, a single smart contract may fulfill one or more of these roles, and its specific qualification should be comprehensively judged in conjunction with its actual functions and usage scenarios.

(3) The Legal Nature of Smart Contracts Used for Money Laundering and Other Illegal Operations

The application of smart contracts in illegal activities is not uncommon, with various complex patterns emerging in the field of money laundering alone. In such cases, the core dispute often does not lie in the legal nature of the smart contract itself, but rather in the fact that once it is used for illegal purposes, the relevant developers, users, and even node participants may face criminal liability or administrative penalties.

Taking the previously mentioned Tornado Cash case as an example: although the sanctions imposed by the U.S. Department of the Treasury have been declared invalid, its developer Roman Storm remains embroiled in legal disputes. Storm has been charged with conspiracy to operate an unlicensed money transmission business, conspiracy to commit money laundering, and conspiracy to violate U.S. sanctions against North Korea. On August 6, 2025, a jury in the federal court in Manhattan, New York, found him guilty of "conspiracy to operate an unlicensed money transmission business," which carries a maximum sentence of five years in prison.

Although the post-trial motions submitted by Storm's defense attorney and the prosecutor have yet to reach a conclusion, this case clearly indicates that against the backdrop of the legal nature of smart contracts remaining ambiguous, the judicial practice's requirements for the responsibility of code developers extend far beyond merely "maintaining technical neutrality" or "avoiding becoming actual controllers."

(4) Smart Contracts as Objects of Intellectual Property Protection

In today's society, the legal protection of intellectual achievements has become a common consensus, but there are still questions regarding whether smart contracts are objects protected by intellectual property rights, and what types of intellectual property they can be protected as (such as copyright, patents, trade secrets), which practitioners need to analyze in conjunction with their forms of expression, innovative content, and protection intentions.

1. The "Text" of Smart Contracts and Copyright

For most programmers, writing smart contract code is primarily aimed at achieving certain functionalities, and they may not necessarily pursue groundbreaking innovations, but this does not mean that their intellectual achievements cannot be protected.

Copyright provides a protection pathway for smart contracts. Although the term "work" easily evokes thoughts of books, paintings, etc., it actually protects the expression forms of intellectual achievements that meet the criteria of "works," rather than the underlying technical ideas or functional logic, and there are no special requirements regarding the "technical" level of the code.

Therefore, if the code of a smart contract meets the criteria of originality, intellectuality, and tangible expression, it may be qualified as a "work" and protected by copyright.

Originality: The code is independently created by the developer, reflecting their personalized choices, arrangements, and expressions, rather than a simple replication of public domain code or generic functions.

Intellectuality: The code is the result of the developer's application of professional knowledge and logical thinking, a direct product of intellectual activity, rather than a mechanical or purely functional arrangement.

Tangible Expression: The code is fixed in text form, making it perceivable, replicable, and disseminable. It should be noted that the scope of copyright protection is limited to the text expression of the code itself and does not extend to the technical solutions, algorithmic ideas, or functional logic it embodies.

If a smart contract is recognized as a work in the sense of copyright law, the rights holder automatically enjoys a series of personal and property rights, such as the right to publish, the right to attribution, the right to modify, the right to reproduce, and the right to disseminate information over networks.

Copyright arises automatically upon the completion of the work, and while it does not require administrative registration to take effect, registering copyright or using reliable timestamping technologies can effectively strengthen proof of ownership in the event of a dispute.

2. The "Technology" of Smart Contracts and Patents

If a smart contract not only contains code expression but also implements a technically innovative solution, it may be qualified as a "patent" and seek protection through patent rights.

Unlike copyright, which arises automatically, patent rights must go through application, examination, and authorization to be obtained. The technical solutions contained in smart contracts must meet the following three criteria to be eligible for patent application:

Novelty: The technical solution does not belong to existing technology and has not been publicly disclosed or used.

Inventiveness: Compared to existing technology, the solution has outstanding substantive characteristics and significant advancements.

Utility: It can be manufactured or used and can produce positive technical effects.

Patents are divided into three categories: invention, utility model, and design, corresponding to different scopes of protection and application strategies. The core of the patent system is "protection in exchange for disclosure," meaning that the applicant fully discloses the technical content to society in exchange for exclusive implementation rights for a certain period. This entails more challenging technical disclosures and stricter examination processes, but it may also lead to longer protection periods and stronger commercial exclusivity.

Whether to apply for patents related to smart contract technologies requires a comprehensive assessment of factors such as the technology lifecycle, market competition, and trade secret protection. Given the high specialization, complexity, and far-reaching implications of patent applications, it is generally advisable to seek assistance from patent attorneys for layout and advancement.

3. The "Information" of Smart Contracts and Trade Secrets

If the technical solutions or business information in a smart contract do not meet the protection conditions of patents or copyrights, or if the developers do not wish to disclose their content, they may consider whether it falls under the category of "trade secrets."

If a contract meets the following criteria, it may be qualified as a "trade secret" and protected as such.

Secrecy: The information has not been publicly disclosed or is not easily obtainable by others through legal means.

Value: It can provide the holder with actual or potential competitive advantages or economic benefits.

Confidentiality Measures: The rights holder has taken reasonable and ongoing confidentiality measures, such as access control, encrypted storage, and signing non-disclosure agreements.

The scope of protection for trade secrets is broad, including technical information and business information that are not known to the public, have commercial value, and for which the rights holder has taken corresponding confidentiality measures. Core algorithms, unique architectures, business logic, or undisclosed parameters in smart contracts can all fall under the category of trade secrets.

Protecting trade secrets does not rely on registration or examination; the main legal means is to sign non-disclosure agreements with internal employees, partners, etc., restricting them from disclosing, using, or allowing others to use the relevant information. This approach does not require technical disclosure but heavily relies on ongoing internal management and compliance supervision to maintain the secrecy of the information.

(5) The Legal Nature of Smart Contracts Used in Litigation

Due to their open, transparent, and immutable technical characteristics, smart contracts are often seen as an ideal form of electronic evidence. However, using them as evidence in legal practice is more complex than traditional forms of evidence. This complexity primarily arises from the following technical features:

Smart contracts are written in code language. On one hand, the professionalism and complexity of the code significantly increase the understanding and argumentation costs in litigation, requiring public authorities and parties to invest more resources in interpretation. On the other hand, the code may not express the parties' entire true intentions as clearly and completely as natural language, and parties may reach consensus outside the contract. Therefore, smart contracts often cannot serve as the sole basis for a ruling and need to be corroborated by other evidence.

Smart contracts have anonymity. In many cases, the identities of the parties operating through smart contracts are difficult to trace directly. Although in major criminal cases such as money laundering, powerful public authorities can use technical means to break through anonymity barriers, in a large number of civil or non-criminal disputes, identity recognition remains a significant challenge.

Smart contracts operate on a decentralized architecture. Their execution does not rely on real-time control by a single center, leading to difficulties in determining responsibility in the event of a dispute—multiple parties, including code developers, deployers, and node participants, may be involved, yet there are no clear legal rules delineating their boundaries of responsibility.

Thus, while the evidentiary effectiveness of smart contracts has not been legally denied, and issues such as the allocation of the burden of proof involved still fall within the framework of traditional evidence rules, the unique nature of their technical language and operational mechanisms indeed imposes higher professional requirements on parties, judicial authorities, and relevant professionals in judicial practice.

Compliance Recommendations for Participants

In the face of the complexity of the legal nature of smart contracts, we can at least do the following:

Dare to protect rights and proactively comply: The development of the industry leads to social changes, inevitably generating many new legal issues. Whether risks or opportunities, practitioners should not lack proactivity.

Clarify scenarios and define precisely: In legal practice, especially in important legal documents, avoid using the term "smart contract" in a vague manner, and provide explanations for the concept when necessary.

When used for transactions, comprehensively focus on legality issues, technical details, and remedies: Both parties to the agreement should at least pay attention to whether the transaction scenario is legal, as well as the security audit of the code, whether it accurately reflects true intentions, and the remedial measures and liability allocation in the event of disputes.

When used for specific functions, search for specialized laws and regulations: The application scenarios of smart contracts are very broad and may involve completely different areas of law. Especially when used in specific fields such as DAOs, finance, and asset issuance, it is essential to check whether there are special laws and regulations in that field or specific region to ensure proactive compliance.

Pay attention to jurisdiction issues and applicable laws: Smart contracts inherently possess cross-border characteristics, but laws are territorial. Even the same smart contract dispute may have different regulations in different regions. Considering these issues at the design stage of the project is very helpful in reducing legal disputes. For example, participants can pre-agree on the applicable law and jurisdictional court or arbitration institution in the event of a dispute, clarifying cross-border legal risks.

Conclusion

The real application scenarios and legal practices are far more complex than what is presented in this article. Therefore, the author does not expect to "clarify" the relevant legal issues through this article but hopes to disseminate relevant legal knowledge and convey the following concept:

In the face of the complexity of smart contract applications, we should abandon the simplistic thinking of "code is law" and instead adopt a more nuanced and pragmatic perspective of "contextual analysis." Only in this way can we clearly define rights and responsibilities, manage benefits and risks while embracing technological innovation.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。