Author: Spinach Spinach

Core Viewpoint:

The issue with digital renminbi has never been about "choosing the wrong path," but rather being locked into the application space by the positioning of M0. Under the premise of adhering to the fundamental path of central bank issuance and sovereign backing, DC/EP has, in the past, resembled a project that is "institutionally correct but productively constrained."

Transitioning from M0 to M1 does not negate the past; it is a necessary paradigm shift: allowing digital renminbi to truly enter high-frequency scenarios, asset choices, and market mechanisms for the first time.

More importantly, the real challenge does not lie in technology or compliance, but in whether there is the courage to leave enough exploratory space for the market under controllable conditions. If digital renminbi can only rely on subsidies and administrative push, it will never form network effects; only by learning to coexist with the market can it "run" like a real currency.

This is the most noteworthy underlying thread behind M1.

This article is authored by Beilong, a good brother of Spinach, who participated in early CBDC-related work.

1 | Don't Rush to Take Sides: This is Not a Route Dispute, but a Stage Difference

If we only look at the results, many people will draw a simple and blunt conclusion: stablecoins have already achieved scale and PMF, while digital renminbi remains lukewarm—does this mean that China chose the wrong path from the beginning?

This judgment is too early and too rash.

We must first acknowledge a premise: China and the West have never been competing on the same track regarding digital currency from the very beginning. The capitalist system represented by the United States is more inclined to leave monetary innovation to the market—stablecoins are issued by commercial entities, circulating freely on-chain, continuously experimenting through DeFi, exchanges, and payment scenarios, first generating demand, and then allowing regulation to mitigate risks.

China, on the other hand, has chosen a different path: the central bank personally promotes CBDC. On this path, sovereign credit, financial stability, and system security are prioritized, and innovation itself must yield to stability.

These two paths address different issues and are destined to present completely different development rhythms.

Looking back today, stablecoins have indeed succeeded, but their success is essentially the success of market mechanisms; the slow advancement of digital renminbi does not equate to failure; it is more like a result of deliberately slowing down under institutional constraints. If a digital currency backed by the central bank and possessing the highest credit rating were allowed to expand fully in a market-oriented manner from the start, the systemic risks it would bring are clearly not something any financial regulator could easily bear.

Therefore, there is no simple comparison of "who is more advanced," but rather the choice of institution determines the order of development.

For ordinary users and entrepreneurs, there is a frequently overlooked but extremely critical conclusion: do not get entangled in "which path is right," because that is not a choice you can make. The "path" is determined by the institution; what can truly be worked on is only the "tech"—within the established framework, making the product more user-friendly, generating real demand, and allowing currency to truly enter high-frequency scenarios.

In this sense, today's discussion of the transition of digital renminbi from M0 to M1 is not about overturning the original route, but acknowledging a reality: if it only stays at "the route is correct" but cannot land on "tech," no matter how correct the path is, it will not yield results.

This round of changes indicates not a change in direction, but a stage shift: the route has not changed, but the gameplay has begun to change.

2 | Why It Had to Be M0 Back Then: Theoretically Correct, but Locked the Product in Low-Frequency Demand

If we are to evaluate the biggest "original sin" of DC/EP (Digital Currency Electronic Payment, specifically referring to China's CBDC) in its early stages, many would point fingers at technology selection, advancement pace, or even conspiratorial interpretations of "conservatism." But the real answer is actually the opposite: the reason DC/EP was strictly positioned as M0 from the beginning was not due to conservatism, but because the theoretical judgment at that time was overly rigorous.

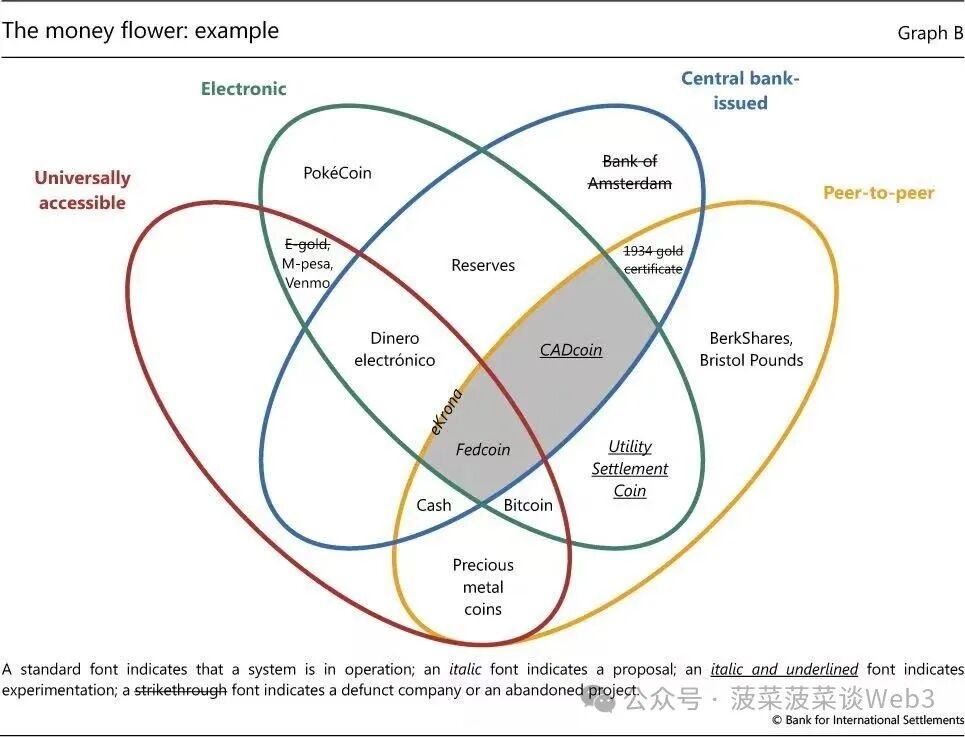

During the project initiation and design phase of digital renminbi, the core theoretical framework referenced by the People's Bank of China was the "Money Flower" analysis framework proposed by the BIS (Bank for International Settlements) in several of its studies. The BIS pointed out in articles like the Quarterly Review that currency can be systematically classified from dimensions such as issuing entities, whether it is digital, whether it is account-based, and whether it is aimed at the public. A compelling conclusion is that among all mainstream forms of currency, only cash has not been truly digitized.

Deposits, transfers, and payment accounts have long been digitized within the banking system and internet platforms; the balances in Alipay and WeChat are essentially technical extensions of commercial bank deposits. In this context, the central bank's judgment became very clear: there is no need to reinvent the wheel. The mission of digital renminbi should be to fill the last gap of "cash," rather than to replace an already highly mature electronic payment system.

Under this M0 positioning, the product design logic of DC/EP naturally pointed towards "digital cash." What it primarily addresses is not "how to manage wealth better" or "how to participate more efficiently in financial markets," but how to ensure that a digital form of currency backed by the central bank remains usable in various complex or even extreme environments.

Thus, we see that DC/EP emphasizes capabilities such as "dual offline payment" in practice—meaning it can still complete point-to-point value transfer without network or real-time account verification. This type of design is not technically simple and indeed addresses some scenarios that traditional electronic payments cannot cover, such as limited networks, weak infrastructure, or special emergency situations.

The problem is that these scenarios are inherently low-frequency scenarios.

When internet payments can complete transactions with extremely low friction most of the time and in most places, a digital currency product that leans more towards "safety net capability" and "resilience design" finds it hard to naturally enter the daily choices of ordinary users. Users will not change their established payment habits just because "it can be used in extreme situations."

In other words, the theory of M0 is valid, and the design is self-consistent, but it inherently locks DC/EP into an "important but not high-frequency" position. This is not a product failure, but rather a positioning that makes it difficult to quickly achieve PMF.

Here’s a little anecdote from back then.

In the early stages of DC/EP, I once chatted with a friend from "Goose Field" about digital renminbi. His evaluation was very direct, even a bit playful: "They (referring to DC/EP) pose no threat to us."

This statement was not dismissive but rather a very calm judgment. From the perspective of internet payment platforms, a product strictly positioned as M0, primarily addressing the digitization of cash, would not directly touch on high-frequency payments, account systems, and user stickiness—these "core battlefields."

Because of this, for a long time, there was no real competitive relationship between digital renminbi and mainstream internet payment systems.

This also marks the starting point for subsequent reflections: when digital renminbi is only allowed to "work like cash," it indeed fulfills its mission; but if we hope for it to "be used like money," then merely having the M0 positioning is clearly insufficient.

3 | One Point That Must Be Made Clear: CBDC and Stablecoins Are Not the Same Type of Currency

Let’s put the conclusion upfront: regardless of how the technical form changes, the issuer of DC/EP can only be the central bank itself. This is not a strategic choice but an institutional premise. Because of this, CBDC and stablecoins have never been "competing peers," but rather different forms of currency under two credit systems.

Many discussions about "why digital renminbi is not as flexible as stablecoins" actually confuse the subjects from the start. The reason stablecoins can expand rapidly and frequently experiment is that they are essentially a type of commercial currency issued by commercial entities: backed by enterprises, bearing commercial credit risks, and competing in the market to gain usage scenarios and liquidity.

In contrast, CBDC is the opposite. It is still issued by the central bank, backed by the central bank's liabilities, and supported by sovereign credit. From a monetary hierarchy perspective, this means higher security and certainty; but from a product form perspective, it also means it must accept stricter boundary constraints. Any "overly aggressive" design could be amplified into systemic financial risks.

For this reason, stablecoins can freely combine on-chain, embed DeFi, and participate in leverage and market-making; while CBDC has chosen cautious restraint for a considerable period. This is not a gap in technical capability, but an inevitable result of differing credit responsibilities.

The interesting part begins here: what happens when the highest credit-rated currency form starts to learn from market mechanisms?

From this perspective, the significance of M1 is not just "can it earn interest," but whether it provides a new possible path for CBDC—introducing incentive structures closer to market demand without changing the issuing entity or sacrificing legal tender status.

In other words, what is truly worth discussing is not "will CBDC replace stablecoins," but rather: under the premise of maintaining sovereign credit, can CBDC catch up with or even partially surpass stablecoins in terms of flexibility and usability?

This is the most noteworthy underlying thread behind the transition from M0 to M1.

4 | From M0 to M1: Digital Renminbi Enters "Asset Choice" for the First Time

To conclude: only when digital renminbi is allowed to enter M1 does it have the opportunity to transform from a "payment tool" into a currency that users actively hold.

Under the M0 framework, DC/EP resembles a digital cash substitute. The core value of cash lies in settlement and payment, not in "holding." You wouldn't take a little more cash just because of the cash itself; cash is merely a medium for completing transactions. Therefore, when digital renminbi is strictly limited to M0, it is inherently difficult to change user behavior—users will only use it when "needed," not when "they can choose."

The introduction of M1 changes this premise for the first time.

M1 represents demand deposits: it can be held, can participate in broader financial activities, and possesses basic yield attributes. Even if this yield is very limited, it will still have a decisive impact on user behavior. Because for the vast majority of users, what is truly unacceptable is not "low yield," but "no yield at all."

It is precisely at this point that digital renminbi begins to form a potential crowding-out effect on existing electronic currency forms. Alipay or WeChat balances are essentially efficient payment tools, but the balances themselves do not carry "asset attributes"; however, once digital renminbi enters M1, even with minimal returns, it begins to have reasons for long-term holding.

It is important to note that this does not mean digital renminbi will replace money market funds or other financial products. On the contrary, M1 digital renminbi is more likely to become a "base": high-frequency liquidity remains in M1, while enhanced returns are achieved through products like MMFs. This layered structure does not conflict; rather, it aligns more closely with the real funding management habits of users.

From this perspective, M1 is not a simple technical upgrade but a fundamental change in product positioning:

From "whether there is cash digitization capability,"

To "whether it can participate in users' asset allocation decisions."

This step is not about whether digital renminbi "can be used," but whether it is worth keeping.

5 | No Need for State Council Approval: A Seriously Underestimated Signal

The conclusion is clear: the removal of the need for special approval at the State Council level means that digital renminbi is transitioning from a "major engineering project" to a more normalized financial infrastructure.

In the previous phase, digital renminbi was primarily advanced through an "experiment—promotion—evaluation" engineering approach. This path was very necessary in the early stages, ensuring system security, controllable risks, and aligning with the central bank's consistent cautious principles. However, the costs were also evident: slow pace, limited scenarios, and restricted innovation space.

When the approval level changes, it essentially releases a signal: under the established institutional framework, more market participants are allowed to engage, more application forms are permitted, and a certain degree of trial and error is allowed.

Currency is never designed; it is filtered through usage. Only when digital renminbi gradually detaches from the context of a "demonstration project" and enters the role of everyday financial infrastructure can it truly run in high-frequency scenarios.

This change does not mean a relaxation of regulation; rather, it signifies a change in regulatory approach: from strictly limiting paths in advance to observing how the market self-organizes within boundaries.

6 | Chain Reactions: From Product Adjustments to Financial Structure Reshaping

The shift from M0 to M1 is not a single-point optimization but a structural change that will continue to release impacts over the coming years.

6.1 Development Path Re-anchored: Domestic CBDC, Offshore Stablecoins

A frequently overlooked but increasingly clear reality is that China does not have to choose between "CBDC or stablecoins."

In the domestic system, promoting CBDC centered around digital renminbi is the optimal solution for sovereign currency and financial stability; while in offshore and cross-border scenarios, especially in highly market-oriented and international financial hubs like Hong Kong, retaining the issuance and application space for stablecoins is more meaningful.

This is not a swing but a form of layered governance:

Domestically, use CBDC to solidify the digital foundation of sovereign currency;

Offshore, connect stablecoins with market mechanisms to tap into global liquidity.

6.2 Potential Pressure on Traditional "Non-Interest-Bearing Stablecoins"

Key judgment: As sovereign credit currency begins to possess M1 attributes, the structural disadvantages of non-interest-bearing stablecoins will gradually be amplified.

The biggest advantage of stablecoins currently lies in their combinability and liquidity, but on the "holding end," most stablecoins do not inherently earn interest. In contrast, once digital renminbi possesses basic yield attributes under the M1 framework, even with very low returns, it will create a significant difference in long-term capital allocation.

This does not mean stablecoins will be quickly replaced, but it indicates a change in the competitive dimension:

In the past, the competition was about "whether it can be used";

In the future, the competition will be about "whether it is worth holding long-term."

6.3 The Central Bank and Commercial Banks Entering Deep Waters

This is the most complex and difficult influence to navigate.

As digital renminbi approaches M1, it essentially means the central bank is beginning to face public liabilities more directly. This change will inevitably touch upon the traditional division of labor between the central bank and commercial banks.

In the existing system, commercial banks play a core role in accounts, deposits, and customer relationships; however, once the central bank digital currency continues to strengthen its account and yield attributes, how to avoid creating a "siphoning effect" on the commercial banking system becomes a necessary issue to address.

It is also in this context that the institutional framework surrounding digital renminbi will eventually touch upon more fundamental legal issues—such as the definitions of the central bank's functions, liability structure, and public relations in the "Central Bank Law."

6.4 The "Loose Boundary" Advantage of USDT/USDC and the Realities CBDC Must Face

An unavoidable fact is that USDT and USDC can be widely used globally not just because of "dollar anchoring," but because they have chosen a side that heavily favors the market between anonymity and controllability.

In practical operation, USDT and USDC naturally possess strong "quasi-anonymous" characteristics on-chain:

Address equals account, not mandatorily bound to real identity;

Transfers have almost no thresholds and can be embedded in various contracts and protocols;

As long as the contract allows, they can be used for trading, collateral, settlement, market-making, and other highly diversified scenarios.

At the same time, they are not completely uncontrolled. Through smart contract permissions, issuer freezing addresses, and cooperation with regulatory enforcement, stablecoins still possess intervention and recovery capabilities "when necessary." However, it should be emphasized that this level of control is deliberately kept extremely loose and occurs more often post-event rather than pre-event.

It is this design of "very loose boundaries, but not zero" that provides the market with significant exploratory space. A large number of DeFi, cross-border settlement, and gray but real demands have been discovered, validated, and amplified in this relaxed environment.

This also raises an unavoidable question: if CBDC remains in a state of highly preemptive control, strong identity binding, and strong scenario limitations, it will be difficult for it to form a true benchmark against stablecoins in terms of application exploration.

Therefore, the transition from M0 to M1 is not just about "whether it earns interest," but about whether the central bank digital currency is willing and able, under controllable risks, to attempt to break overly conservative usage boundaries.

This is not about replicating the paths of USDT or USDC, but about answering a more realistic question: under the premise of maintaining legal tender status and sovereign credit, can CBDC leave enough "exploratory space" for the market?

Only by taking substantial steps on this issue can digital renminbi truly enter scenarios that are still occupied by stablecoins today.

6.5 Systematic Opening of Application Scenarios

When digital renminbi is no longer just a "payment demonstration" or "cash substitute," but enters the M1 system, its potential application scenarios will be systematically opened:

Public payments such as wages and subsidies

Inter-institutional and inter-system settlements

Deep integration with financial products and contract-based payments

These scenarios will not explode overnight, but they determine that digital renminbi is no longer just a "sample demonstrating technical capabilities," but truly enters the main flow of financial operations.

7 | A Direction Worth Serious Discussion: The "Dual-Track Design" of Onshore and Offshore Digital Renminbi

Let’s state the core judgment: if we hope for digital renminbi to truly "run" globally, it may be necessary to clearly distinguish between "onshore digital renminbi" and "offshore digital renminbi" in institutional design.

This is not radical innovation but a choice of realism.

Onshore digital renminbi continues to serve the domestic financial system, with its core goal still being manageable, controllable, and traceable. Through a tiered account system, real-name requirements, and scenario limitations, it ensures that the overarching premises of anti-money laundering, anti-terrorist financing, and financial stability are not undermined. This logic is necessary and reasonable in the domestic environment.

However, the problem is: if the same constraints are copied unchanged into cross-border and offshore scenarios, digital renminbi is unlikely to form real international usage momentum.

In contrast, USDT and USDC have been able to spread rapidly in overseas markets, partly because they provide stronger quasi-anonymity by default: addresses equal accounts, and identities are not pre-bound; regulation and intervention occur more often post-event rather than pre-event. This design does not encourage violations but leaves enough space for market exploration.

Following this logic, a proposal worth serious discussion is to introduce stronger, mathematically provable anonymity for offshore digital renminbi.

The anonymity referred to here is not completely uncontrollable but is achieved through cryptographic means to enable "selective disclosure" and "conditional traceability":

In daily transactions, users do not need to expose their full identity;

When specific legal conditions are triggered, traceability can be restored through compliance processes;

The control logic shifts from "completely preemptive" to "limited preemptive + post-event intervention."

Such a design would make offshore digital renminbi functionally closer to stablecoins while still maintaining the advantages of sovereign currency at the credit level. This is precisely what current commercial stablecoins cannot provide.

From a strategic perspective, this "dual-track design" would not weaken domestic regulation; rather, it could create clear divisions of labor:

Onshore, digital renminbi continues to play the role of financial infrastructure and policy tool;

Offshore, digital renminbi takes on the roles of "international settlement currency" and "export of digital renminbi."

If this idea can be realized, then digital renminbi will no longer just be an upgrade of the domestic payment system but could become a key lever in the process of renminbi internationalization.

This is not a risk; on the contrary, it could be a truly significant "good thing."

8 | The Real Challenge: It's Not About "Can It," But About "Dare We Let the Market Run Free"

To clarify the conclusion: the biggest challenge facing digital renminbi next is not at the technical level or in terms of institutional legality, but in whether there is a willingness to leave enough freedom for the market under controllable conditions.

Looking back at the development path of stablecoins, an often overlooked but extremely important fact is that the success of USDT and USDC was not "planned out," but rather emerged gradually through a series of imperfect, even gray, uses in the market. Cross-border transfers, on-chain transactions, DeFi collateral, settlement intermediaries… none of these scenarios were pre-approved by regulatory authorities as "acceptable uses," but they naturally grew out of real demand.

In contrast, if digital renminbi continues to primarily rely on subsidies, administrative promotion, or demonstration projects to expand its use cases, then no matter how advanced the technology or how high the credit rating, it will be difficult to form a true network effect. Once a currency fails to create a network effect, it will forever remain in the realm of "being required to use" rather than "being actively chosen."

This is also why the real watershed is not about "whether to insist on legal tender status." Legal tender status is the baseline, not an obstacle. The real challenge lies in whether, while adhering to legal tender status, it is possible to accept a more market-oriented exploratory approach, allowing some applications to emerge ahead of the rules, which can then be absorbed and regulated by those rules.

In this sense, the "dual-track design" of onshore and offshore is not a weakening of regulation, but a more refined risk layering:

High-risk, strong exploratory demands remain in the offshore system for trial runs;

High-certainty, strong stable demands continue to operate within the onshore system.

This is not about laissez-faire; rather, it is a conscious choice to provide a margin for error for innovation.

If the M0 phase of digital renminbi addresses the question of "can the central bank issue digital currency," then starting from M1, the real question becomes: can a digital currency issued by the central bank learn how to coexist with the market without losing control?

There are no ready-made answers to this step, nor can it be achieved overnight. But it is certain that if this step is not taken, digital renminbi will forever remain a "safe cornerstone" in the financial system, and it will be difficult to become a truly liquid currency in the global system.

Conclusion | It's Not That the Route Was Wrong, But That We Have Finally Reached the Stage Where We Can "Let It Run"

Returning to the initial question: why has digital renminbi seemed "lukewarm" in the past?

The answer may not be complicated—it has been locked in a position of excessive restraint by the correct theory of M0.

Today, as we move from M0 to M1, from engineering-driven advancement to infrastructure-based operation, and from a singular domestic logic to a dual design of onshore and offshore, the signals released are very clear:

The route has not changed, but the stage has.

What digital renminbi truly needs to answer next is no longer "is it legal," but rather:

Under the premise of maintaining sovereign credit and financial stability, can it truly learn to work—like money?

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。