Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translation by: Saoirse, Foresight News

Many of us harbor a wariness towards "Big Business." We appreciate the products and services provided by corporations, yet we resent the monopolistic closed ecosystems worth trillions of dollars, the quasi-gambling nature of video games, and those companies that manipulate entire governments for profit.

Many of us also fear "Big Government." We need police and courts to maintain public order and rely on the government to provide various public services, yet we are dissatisfied with the government's arbitrary designation of "winners" and "losers," the restriction of free speech, freedom to read, and even freedom of thought, and we oppose government violations of human rights or waging wars.

Finally, many of us are also afraid of the third corner of this triangle: the "Big Mob." We recognize the value of independent civil society, charitable organizations, and Wikipedia, yet we detest mob justice, cultural boycotts, and extreme events like the French Revolution or the Taiping Rebellion.

Essentially, we yearn for progress—whether in technology, economy, or culture—but we also fear the three core forces that have historically driven this progress.

To break this deadlock, a common approach is the idea of power balance. If society needs strong forces to drive development, then these forces should balance each other: either through internal balance within a single force (such as competition among businesses) or through checks and balances between different forces, ideally combining both.

Historically, this balance has largely formed naturally: due to geographical distance limitations or the need to coordinate large-scale human efforts to accomplish global tasks, the natural phenomenon of "diminishing returns to scale" has constrained excessive concentration of power. However, in this century, this rule no longer holds: the three forces mentioned above are simultaneously becoming increasingly powerful and inevitably interacting with each other frequently.

In this article, I will delve into this topic and propose several strategies to safeguard the increasingly fragile "power balance" characteristic of today's world.

In a previous blog post, I described this emerging world where "Big X" will exist in all fields as a "dense jungle."

Why We Fear Big Government

People's fear of government is not without reason: governments wield coercive power and are fully capable of causing harm to individuals. The power to destroy individuals that governments possess is far beyond what even Mark Zuckerberg or cryptocurrency practitioners could hope to attain. For this reason, for centuries, liberal political theory has revolved around the core issue of "taming the Leviathan"—enjoying the benefits of government maintaining law and order while avoiding the pitfalls of "monarchs having arbitrary control over subjects."

(Taming the Leviathan refers to a political science concept that involves constraining the government, which possesses strong coercive power but may infringe on individual rights, through institutional designs such as the rule of law, separation of powers, and decentralization, ensuring it maintains social order while preventing abuse of power and balancing public order with individual freedom.)

This theoretical framework can be condensed into one sentence: the government should be a "rule maker," not a "game player." In other words, the government should strive to be a reliable "playing field" that efficiently resolves interpersonal disputes within its jurisdiction, rather than an "actor" pursuing its own goals.

There are various paths to achieve this ideal state:

- Libertarianism: believes that the rules the government should enforce essentially boil down to three—no fraud, no theft, no murder.

- Hayekian liberalism: advocates avoiding central planning; if intervention in the market is necessary, it should be goal-oriented rather than method-specific, leaving implementation to market exploration.

- Civil libertarianism: emphasizes freedom of speech, religion, and assembly, preventing the government from imposing its preferences in cultural and ideological domains.

- Rule of law: the government should clearly define "what can and cannot be done" through legislation, with courts responsible for enforcement.

- Supremacy of common law: advocates for the complete abolition of legislative bodies, with a decentralized court system making rulings on individual cases, each ruling forming a precedent that gradually evolves the law.

- Separation of powers: divides government power into multiple branches, with mutual oversight and checks among them.

- Subsidiarity principle: asserts that issues should be resolved by the most local and capable institutions, minimizing the concentration of decision-making power.

- Multipolarity: at least avoids a single country dominating globally; ideally, it should also achieve two additional checks:

- Prevent any country from forming excessive hegemony in its region;

- Ensure that every individual has multiple "backup options" to choose from.

Even in governments that are traditionally not "liberal," similar logic applies. Recent studies have found that in governments classified as "authoritarian," "institutionalized" governments often promote economic growth more effectively than "personalized" governments.

Of course, completely avoiding the government becoming a "game player" is not always achievable, especially in the face of external conflicts: if "players" declare war on the "rules," the inevitable victor will be the "players." However, even when the government needs to temporarily assume the role of a "player," its power is usually subject to strict limitations—such as the "dictator" system in ancient Rome: dictators had significant power during emergencies, but once the crisis was resolved, power would revert to normal.

Why We Fear Big Business

Criticism of corporations can be succinctly categorized into two types:

- Corporations are bad due to "inherent evil."

- Corporations are bad due to "lack of vitality."

The root of the first type of problem (corporate "evil") lies in the fact that corporations are essentially efficient "goal optimization machines," and as their capabilities and scale expand, the core goal of "profit maximization" increasingly diverges from the interests of users and society as a whole. This trend is evident in many industries: in the early stages, industries are often driven by enthusiasts and are vibrant, but over time, they become profit-oriented, ultimately conflicting with user interests. For example:

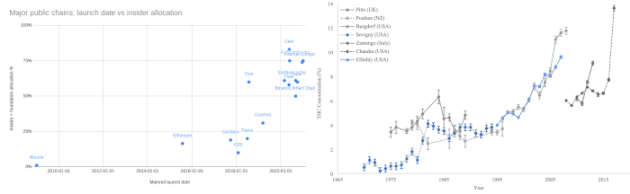

Left: The proportion of tokens directly allocated to insiders among newly issued cryptocurrencies from 2009 to 2021; Right: The concentration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC, the psychoactive component) in cannabis from 1970 to 2020.

The video game industry also exhibits this trend: this field, initially centered on "fun and achievement," increasingly relies on built-in "slot machine mechanisms" to extract maximum funds from players. Even mainstream prediction markets are beginning to show concerning tendencies: no longer focusing on "optimizing news media" or "improving governance" for the benefit of society, but rather concentrating on sports betting.

The aforementioned cases stem more from the combination of enhanced corporate capabilities and competitive pressures, while another type of case is directly related to corporate scale expansion. Generally speaking, the larger a corporation, the more capable it is of distorting its surrounding environment (including economic, political, and cultural factors) to achieve its own interests. A corporation that expands tenfold can, to some extent, increase the benefits gained from distorting the environment by tenfold as well—thus, it will engage in such behaviors far more frequently than smaller businesses, and once it acts, the resources it deploys will be ten times that of smaller firms.

From a mathematical perspective, this aligns with the logic of "why monopolistic firms set prices above marginal costs, increasing profits at the expense of social welfare loss": in this scenario, "market price" is the distorted "environment," and monopolistic firms distort the environment by limiting output. The strength of distortion capability is proportional to market share. But in more general terms, this logic applies to various scenarios, such as corporate lobbying, De Beers-style cultural manipulation activities, etc.

The second type of problem (corporate "lack of vitality") manifests as corporations becoming dull and risk-averse, resulting in large-scale homogenization both within and between companies. (The uniformity of architectural styles is a typical manifestation of corporate "lack of vitality.")

Architectural uniformity is a typical form of corporate mediocrity.

The term "soulless" is interesting—it carries meanings that lie between "evil" and "lack of vitality." Describing a corporation as "addicting users for clicks," "forming cartels to raise prices," or "polluting rivers" fits well; similarly, using it to describe a corporation as "making global cities look alike" or "producing ten Hollywood movies with similar plots" is equally fitting.

I believe that the roots of these two types of "soulless" phenomena lie in two factors: common motives and institutional commonality. All corporations are highly driven by "profit motives," and if many powerful entities share the same strong motive without strong counterbalancing forces, they will inevitably move in the same direction.

"Institutional commonality" arises from corporate scale expansion: the larger the corporation, the more motivated it is to "shape the environment." A corporation valued at $1 billion will invest far more in "shaping the environment" than 100 corporations valued at $10 million each; at the same time, scale expansion exacerbates homogenization—the contribution of Starbucks to "urban homogenization" far exceeds the combined contributions of 100 competitors each only 1% of its size.

Investors may exacerbate these two trends. For a (non-antisocial) startup founder, growing a company to a $1 billion scale and benefiting the world is more satisfying than growing it to a $5 billion scale but harming society (after all, the yachts and planes that $4.9 billion can buy are not worth trading for "being hated by the world"). However, investors are further removed from the "non-financial consequences" of their decisions: as market competition intensifies, investors willing to pursue a $5 billion scale will receive higher returns, while those satisfied with a $1 billion scale will receive lower (or even negative) returns, making it difficult to attract funding. Additionally, investors holding shares in multiple portfolio companies often passively drive these companies to form a certain degree of "merged super entities." However, both trends face an important limiting factor: investors' "monitoring ability" and "accountability" regarding the internal situations of their portfolio companies are limited.

Meanwhile, while market competition can alleviate "institutional commonality," whether it can alleviate "motive commonality" depends on whether different competitors possess "non-profit-oriented differentiated motives." In many cases, corporations do indeed have such motives: for example, sacrificing short-term profits in the name of "publicly sharing innovative results," "upholding core values," or "pursuing aesthetic value." But this situation does not necessarily occur.

If "motive commonality" and "institutional commonality" lead corporations to be "soulless," then what exactly is "soul"? I believe that in the context of this article, "soul" essentially refers to diversity—specifically, the non-homogeneous characteristics among corporations.

Why We Fear the Big Mob

When people talk about "civil society"—the part of society that is neither profit-oriented nor governmental—they often describe it as "composed of numerous independent institutions, each focusing on different areas." If artificial intelligence were to explain "civil society," the examples it would provide would likely be similar.

However, when people criticize "populism," the image that often comes to mind is the opposite scenario: a charismatic leader inciting millions to follow them, forming a large group pursuing a singular goal. Populism, while claiming to represent "the common people," fundamentally constructs the illusion of "people united"—and this "unity" often manifests as support for a particular leader and opposition to a "hated external group."

Even when people criticize civil society, the argument typically revolves around "its failure to achieve the mission of 'numerous independent institutions each showcasing their strengths,' instead promoting some spontaneously formed common agenda"—for example, the phenomenon criticized by the "Cathedral" theory.

The Balance of Power

In all the aforementioned cases, we discuss the power balance within each of the three major "forces." However, different forces can also form checks and balances, with the most typical case being the power balance between government and business.

The capitalist democratic system is essentially a theory of power balance between "Big Government" and "Big Business": entrepreneurs possess legal tools to challenge government actions and can gain the ability to act independently through capital concentration, while the government can regulate businesses.

"Palladium-ism" praises billionaires, specifically those who "act unconventionally to pursue their specific visions rather than directly seeking profit." From this perspective, "Palladium-ism" can be seen as an attempt to "obtain the benefits of capitalism while avoiding its downsides."

While both the government and the market created the necessary conditions for the "Starship" project, it was ultimately neither profit motives nor government directives that drove its inception.

My personal view on philanthropy is, in some ways, similar to "Palladium-ism." I have repeatedly expressed support for billionaires engaging in philanthropy and hope for more individuals to participate. However, the philanthropy I advocate is one that can "balance other social forces." The market often hesitates to fund public goods, while the government is often reluctant to finance projects that "have not yet become elite consensus" or "whose beneficiaries are not concentrated in a single country." Some projects meet both criteria and are thus overlooked by both the market and the government—wealthy individuals can fill this gap.

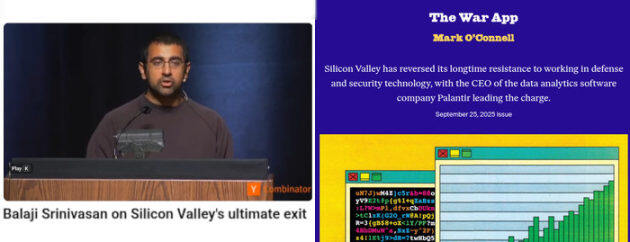

However, billionaire philanthropy can also take a harmful direction: when it ceases to be a "counterbalancing force" to the government and instead replaces the government in wielding power. In recent years, Silicon Valley has witnessed such a shift: powerful tech company CEOs and venture capitalists have become less committed to liberalism and the support of "exit mechanisms," and more focused on directly pushing the government towards their preferred goals—in exchange, they have made the world's most powerful government even stronger.

I prefer the scene on the left (2013) to the one on the right (2025): because the left reflects a balance of power, while the right shows two powerful factions that should counterbalance each other merging instead.

The other two sets of forces in the triangular relationship can also form a power balance. The concept of the "Fourth Estate" (the media) proposed during the Enlightenment essentially positions civil society as a force to check government power (at the same time, even without censorship, power can flow in reverse: the government can profoundly influence educational content through funding primary and secondary schools and universities, especially in primary and secondary education). On the other hand, the media reports on business dynamics, and successful business figures also provide funding support to the media. As long as there is no monopoly of power in a single direction, these mechanisms are healthy and can enhance societal robustness.

Power Balance and Economies of Scale

If one were to find an argument that explains both the rise of the United States in the 20th century and China's development in the 21st century, the answer is simple: economies of scale. This point is often used by individuals from both the U.S. and China to criticize Europe: Europe has many small and medium-sized countries with diverse cultures, languages, and systems, making it difficult to cultivate large enterprises that cover all of Europe; whereas in a large, culturally homogeneous country, businesses can easily scale up to hundreds of millions of users.

The impact of economies of scale is crucial. At the level of human development, we need economies of scale—because it is the most effective way to drive progress to date. However, economies of scale are also a double-edged sword: if my resources are twice yours, the progress I can achieve will be more than double; thus, by next year, my resources may become 2.02 times yours. Over time, the most powerful entities will ultimately control everything.

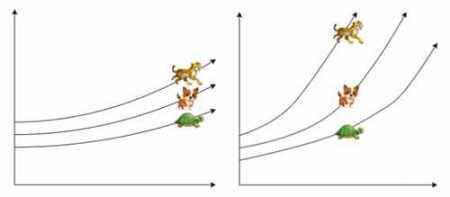

Left: Proportional growth—small initial differences will ultimately remain small; Right: Growth under economies of scale—small initial differences will become significant over time.

Historically, two forces have countered the effects of economies of scale, preventing them from leading to power monopolies:

- Diseconomies of scale: large institutions are inefficient in many ways, such as internal conflicts of interest, communication costs, and costs arising from geographical distance.

- Diffusion effects: when personnel move between companies and countries, they carry away their ideas and skills; underdeveloped countries can achieve "catch-up growth" through trade with developed countries; industrial espionage is ubiquitous, and innovative results can be reverse-engineered; companies can use one social network to drive traffic to another.

If we compare "scale leaders" to cheetahs and "scale laggards" to turtles, then "diseconomies of scale" will slow down the cheetah, while "diffusion effects" act like a rubber band, pulling the turtle closer to the cheetah. However, in recent years, several key forces have been changing this balance:

- Rapid technological advancement: making the "super-exponential growth curve" of economies of scale steeper than ever before.

- Automation: allowing global tasks to be completed with minimal manpower, significantly reducing the costs of human coordination.

- The proliferation of proprietary technology: modern society can produce proprietary software and hardware products that "open only for use rights, not for modification and control rights." Historically, delivering products to consumers (whether domestically or internationally) necessarily meant allowing the other party to inspect and reverse-engineer them—but this rule no longer holds.

Essentially, the effects of economies of scale are continuously strengthening: although the breadth of "idea diffusion" may exceed that of the past due to the influence of internet communication, the "diffusion of control" is weaker than ever.

The Core Dilemma: In the 21st century, how do we achieve rapid progress and build a prosperous civilization while avoiding extreme concentration of power?

The Solution: Force more "diffusion."

What does "force more diffusion" specifically refer to? First, we can look at several government policy examples:

- The EU's mandatory standardization requirements (such as the recently implemented USB-C interface standard): which increase the difficulty of creating "proprietary ecosystems incompatible with other technologies."

- China's mandatory technology transfer rules.

- The U.S. ban on non-compete agreements: I support this policy because it forces the "tacit knowledge" within companies to achieve a degree of "open sourcing"—employees can apply the skills learned at one company to other fields after leaving, benefiting more people. While confidentiality agreements may limit this process, fortunately, they are riddled with loopholes in practice.

- Copyleft licenses (such as the GPL agreement): which require any software developed based on Copyleft code to also adopt an open-source model and be subject to Copyleft licensing.

We can propose more ideas along this direction: for example, the government could draw inspiration from the "EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism" to design a new tax mechanism—levying corresponding taxes on domestic and foreign products based on their "degree of proprietary nature" (measured by some standard); if a company shares technology with society (including through open-source means), the tax rate could be reduced to zero. Another idea worth reviving is the "Intellectual Property Haberg Tax" (taxing intellectual property based on valuation to incentivize owners to utilize intellectual property efficiently).

Additionally, we should adopt a more "flexible" strategy: adversarial interoperability.

As Cory Doctorow (a well-known science fiction writer, blogger, and journalist) explains:

"Adversarial interoperability refers to developing new products/services without obtaining permission from existing product/service manufacturers and making them compatible with existing products/services. Examples include third-party printer ink, alternative app stores, or independent repair shops that use compatible parts produced by competitors to provide repair services for cars, phones, or tractors."

Essentially, this strategy is about "interacting with tech platforms, social media sites, businesses, and governments in an unlicensed manner while benefiting from the value they create."

Specific examples might include:

- Alternative clients for social media platforms: users can view content posted by others, publish their own content, and choose their own content filtering methods through such clients.

- Browser extensions with the same functionality: similar to ad blockers, but specifically targeting AI-generated content on platforms like X.

- Decentralized anti-censorship exchanges between fiat and cryptocurrencies: such exchanges can alleviate the "bottleneck risk" of centralized financial systems (the problem of single points of failure leading to system paralysis).

Overall, much of the value capture in Web2 occurs at the user interface level. Therefore, if we can develop "alternative interfaces that can interoperate with platforms and other users using existing interfaces," users can remain within that network while avoiding the platform's value extraction mechanisms.

Sci-Hub is a typical tool for "forced diffusion"—it has undoubtedly played an important role in enhancing fairness and open access in the field of science.

The third strategy to enhance "diffusion effects" is to return to the concept of "diversity" proposed by Glen Weyl and Audrey Tang. They describe this concept as "facilitating collaboration between differences"—allowing people with differing viewpoints and goals to communicate and cooperate better, enjoying the "efficiency gains from joining large groups" while avoiding the downsides of "large groups becoming single-goal-driven entities." Such concepts can help open-source communities, national alliances, and other non-monolithic groups enhance their "level of diffusion," allowing them to share more of the benefits of economies of scale while remaining competitive with more tightly organized centralized giants.

It is important to note that this line of thought structurally resembles Piketty's theory of "r > g" (the return on capital is greater than the growth rate of the economy) and his proposal to address wealth concentration through a global wealth tax (and strengthened public services). The core difference between the two is that we do not focus on "wealth" itself, but trace upstream to the "source of unrestricted wealth concentration"—what we aim to diffuse is not money, but the means of production.

I believe this approach is superior for two reasons: first, it directly targets the "dangerous core" (the combination of "extreme growth" and "exclusivity"), and if executed properly, it could even enhance overall efficiency; second, it is not limited to addressing a specific type of power—while a global wealth tax may prevent the concentration of power among billionaires, it cannot restrain authoritarian governments or other multinational entities, and may even leave us more vulnerable in the face of these forces. In contrast, "forcing technological diffusion through a global decentralized strategy"—clearly informing all parties that "either grow with us and share core technologies and network resources at a reasonable pace, or develop in complete isolation and be excluded by us"—can address the issue of power concentration in a more comprehensive manner.

D/acc: Making a Multipolar World Safer

Pluralism faces a theoretical risk known as the "fragile world hypothesis": as technology advances, there may be an increasing number of entities capable of causing "catastrophic harm to all humanity"; the weaker the world's coordination, the higher the probability that one of these entities will choose to inflict such harm. In response, some believe the only solution is to "further concentrate power"—but this article advocates precisely the opposite: "reducing power concentration."

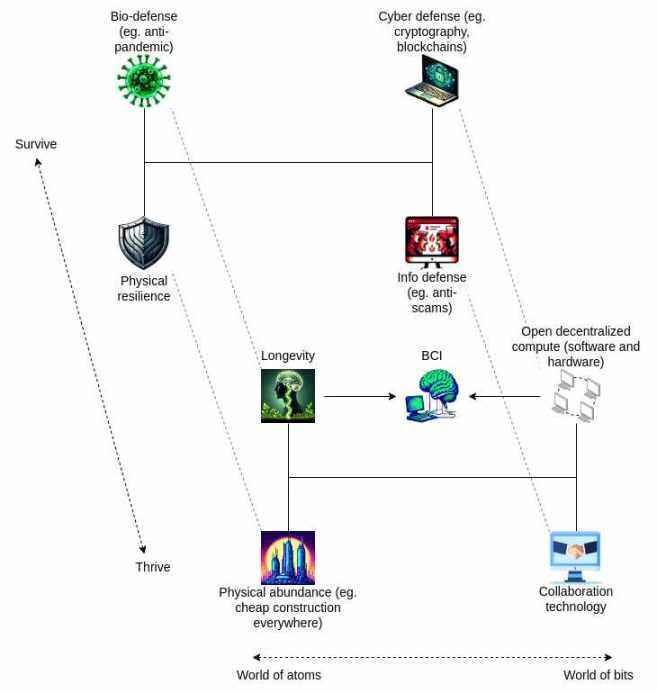

D/acc (Defensive Accelerationism) is a complementary strategy that allows for the safer realization of the goal of "reducing power concentration." Its core is "building defensive technologies that develop in sync with offensive technologies," and these defensive technologies must be open and inclusive, allowing everyone to access them—this way, we can reduce the demand for power concentration driven by "security anxiety."

D/acc Technology Cube Diagram

The Moral Perspective of Pluralism

The enslavement moral perspective holds that: you are not allowed to become powerful.

The master moral perspective holds that: you must become powerful.

In contrast, a comprehensive moral perspective centered on power balance may suggest: you are not allowed to form hegemony, but you should pursue positive impact and empower others.

This viewpoint is essentially a reinterpretation of the "empowerment rights" versus "control rights" dichotomy that has existed for hundreds of years.

To achieve "having empowerment rights without holding control rights," there are two paths: one is to maintain a high degree of "diffusiveness" towards the external world; the other is to minimize the possibility of being "used as a lever of power" when constructing systems.

In the Ethereum ecosystem, the decentralized staking pool Lido is a good example. Currently, the amount of ETH staked managed by Lido accounts for about 24% of the total staked amount across the network, but people's level of concern about it is far lower than for "any other entity holding 24% of the staked amount." The reason is that Lido is not a single entity: it is an internally decentralized DAO with dozens of node operators and employs a "dual governance" design—ETH stakers have veto power over decisions. Lido's efforts in this direction are commendable. Of course, the Ethereum community has also made it clear that even with these safeguards, Lido should not control the entire staked amount of Ethereum—currently, it is still far from this risk threshold.

In the future, more projects should clearly consider two core questions: not only how to design a "business model"—that is, how to acquire resources to support their operations; but also how to design a "decentralized model"—that is, how to avoid becoming a node of power concentration and how to address the "risks that come with holding power."

In some scenarios, decentralization is relatively easy to achieve: for example, few people mind the dominance of English, and few worry about the widespread use of open protocols like TCP, IP, and HTTP. However, in other scenarios, decentralization poses significant challenges—because certain application scenarios "require entities to have clear intentions and capabilities for action." How to retain the "advantage of flexibility" while avoiding the "downsides of power concentration" will be an important challenge faced in the long term.

Special thanks to Gabriel Alfour, Audrey Tang, and Ahmed Gatnash for their feedback and review.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。