Author: Lawyer Shao Shiwei

Criminal cases involving virtual currencies are gradually becoming a hot topic in judicial practice, moving from a relatively niche area of case handling. In recent years, legal determinations and judicial disputes surrounding charges such as "virtual currency crimes," "illegal business operations," and "USDT trading" have garnered increasing attention. Lawyer Shao has represented multiple cases in recent years where individuals were charged with illegal business operations for trading virtual currencies.

Therefore, this article will analyze and discuss the focal issue of whether "cross-border arbitrage by U merchants constitutes illegal business operations," combining the latest published typical cases and practical experiences, from the perspectives of legal qualification, defense strategies, and judicial trends.

1. Why is trading USDT recognized as illegal business operations? Analysis of typical cases

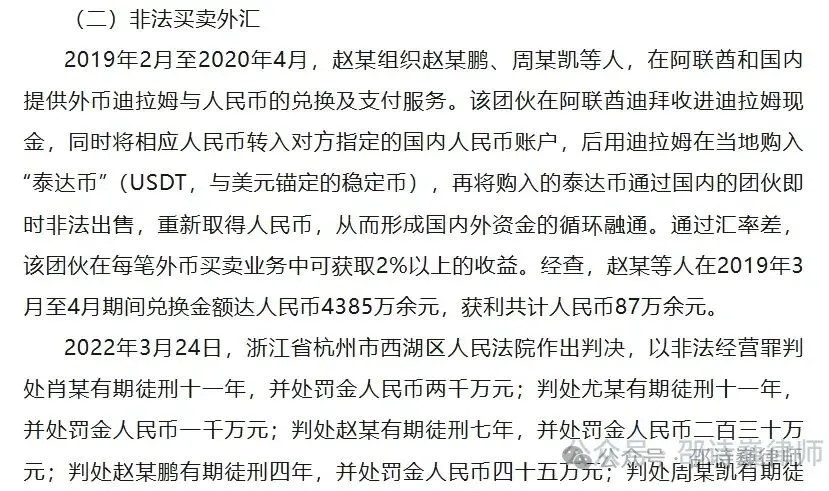

The case of Zhao and others, prosecuted for illegal business operations by the People's Court of Xihu District, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province in 2022 (Zhao Dong case), is a representative case where individuals were charged with illegal business operations for engaging in cross-border arbitrage through the trading of virtual currencies. This case has also been listed as a typical case for punishing illegal foreign exchange crimes by the Supreme People's Procuratorate and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange.

From the official case report, it can be seen that the behavior of the parties involved was to engage in cross-border "arbitrage" through the buying and selling of USDT and other virtual currencies, which led to their prosecution for illegal business operations.

Based on the limited information currently disclosed by officials, it seems possible to preliminarily conclude that any behavior involving cross-border arbitrage of virtual currencies, earning exchange rate differences, and involving the exchange of fiat currencies from different countries may fall within the scope of illegal business operations.

However, from a cautious and questioning standpoint, this conclusion itself still warrants further inquiry: Does the direct application of illegal business operations to such behavioral patterns truly align with the boundaries and logic of criminal law evaluation?

Even though this case has already resulted in a final judgment, the judgment was made four years ago. Cases involving currencies have long been in a state of lacking clear legislative rules, and the handling paths in judicial practice have gradually explored based on the spirit of policies such as the "94 Announcement" and "924 Notice," advancing through continuous experimentation. Whether the standards for adjudication are stable and replicable remains to be observed.

Combining the following two reports, it can be seen that the aforementioned judgment has indeed seen some noteworthy new changes in judicial practice and legal application.

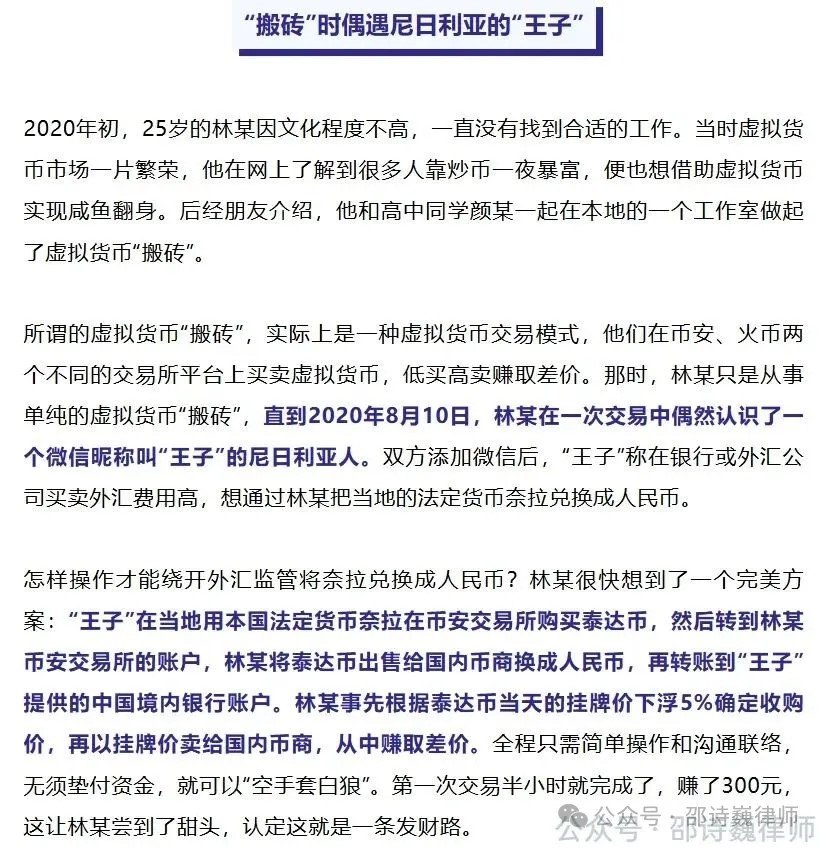

The first report is from the Jiangsu Province Jianhu County Procuratorate in 2024, regarding the Lin and Yan illegal business case:

Regarding whether "cross-border arbitrage of virtual currencies" constitutes legal arbitrage or illegal business operations, the officially disclosed case details provide a relatively clear entry point.

From the case details, Lin's so-called "arbitrage" was essentially directed by a Nigerian "prince": the prince transferred naira into Lin's Binance account, and Lin then sold the received USDT to domestic U merchants in exchange for RMB, returning the funds to the prince. Lin determined the purchase price by applying a 5% discount to the day's USDT listing price and then sold it to U merchants at the listing price, earning the price difference.

The value of this case lies in its relatively clear definition of the core reason for criminalizing the behavior: the issue does not lie in the form of "arbitrage" itself, but in its true business model— the actor is not independently conducting market arbitrage but is substantively providing exchange services for others using virtual currencies as a medium. Because of this, the nature of their behavior fundamentally shifted from "arbitrage behavior" to "illegal business operations."

As time progressed to 2025, discussions in judicial practice further deepened.

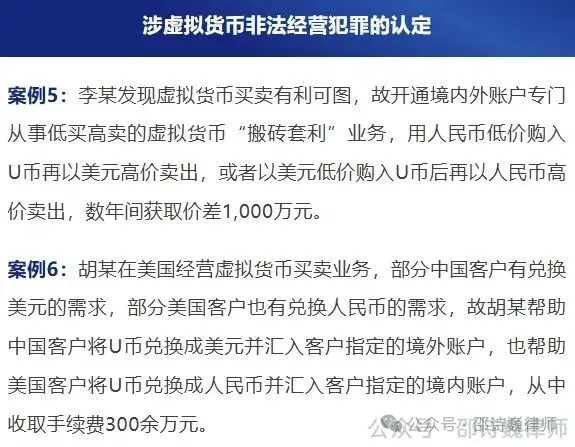

On December 17, 2025, the Shanghai Second Intermediate Court published a summary: Theoretical and Practical Collaboration | Legal Uniformity in Cases Involving Virtual Currency Crimes.

This article systematically reviews the legal application issues in cases involving illegal business operations related to virtual currencies, listing two types of situations and discussing whether they constitute illegal business operations in a more cautious and in-depth manner.

The article mentions:

For Case 5, if Li's behavior does not exhibit characteristics of business operations and is merely personal holding or trading of currencies, it is generally not recognized as illegal business operations. However, if he knowingly assists others in illegal buying or selling or indirectly buying and selling foreign exchange through virtual currency exchanges, and the circumstances are serious, he should be recognized as an accomplice to illegal business operations.

In Case 6, Hu's behavior exhibits characteristics of regularity and profitability, and he knowingly provides "local currency-virtual currency-foreign currency" exchange and payment services outside the state-designated trading venues, which constitutes indirect buying and selling of foreign exchange, and he illegally profited over 3 million yuan, which should be recognized as illegal business operations.

From this, it is clear that compared to the earlier rough handling approach of "any cross-border arbitrage involving virtual currencies constitutes a crime," some judicial authorities are now beginning to pay more attention to the detailed analysis of the essence of behavior, transaction structure, fund flow, and social harm. This change at least indicates one fact: the adjudication logic in cases involving virtual currencies is shifting from simple application of charges to more refined judgments.

The situations disclosed in these official cases also exist in the past cases represented by Lawyer Shao. Therefore, how should the judicial system accurately delineate the boundaries between crime and non-crime for behaviors such as "buying and selling virtual currencies and engaging in arbitrage"?

Next, Lawyer Shao will further dissect this issue from practical experience: under what circumstances might the relevant behavior be recognized as illegal business operations? And under what circumstances should it not be included in the evaluation scope of illegal business operations?

2. Does trading USDT virtual currency constitute illegal business operations? We should adhere to "specific issues analyzed specifically"

First, we must confront a very practical issue:

The reason why certain cases can become guiding cases is often because their evidence chain is complete, the facts are clear, and the arguments are sufficient, standing up to repeated scrutiny. However, in real judicial practice, many cases are quite the opposite—evidence is insufficient, yet they still "copy the model," simply referencing the conclusions and spirit of guiding cases to render guilty evaluations against the parties involved.

From the perspective of safeguarding the rights of the parties and the standards of criminal evidence, this practice itself is worth cautioning against.

It is precisely in this context that one of the core values of defense lawyers lies in: through the dissection of evidence and factual details, enabling case handlers to truly understand the essential differences between the current case and the so-called "reference case," and thus judge whether the case is comparable and whether it is suitable as a basis for adjudication.

Secondly, the so-called "typical cases" also have obvious temporal and contextual limitations.

They can serve as references, but they are not "sacred edicts" that must be followed at all times, nor should they be mechanically applied to any specific case. For legal professionals, maintaining a necessary spirit of skepticism and independent judgment is a basic professional quality, not an optional attitude.

Based on the above premises, when handling cases involving "virtual currency arbitrage," at least two core questions need to be directly addressed:

Question 1: How to determine in specific cases whether a certain U merchant's "arbitrage" constitutes legal arbitrage or has already constituted business operations?

Question 2: If the profit model of the so-called arbitrage not only derives from exchange rate differences but also includes a certain proportion of "service fees" or "handling fees," does this necessarily constitute illegal business operations?

These two questions are raised because a very practical contradiction has long existed:

Legal provisions, officially disclosed typical cases, and theoretical discussions often present a relatively clear "black or white" logic; however, when it comes to specific criminal cases, the real situation is often highly complex and the boundaries are blurred, far from being covered by simple application of conclusions.

It is precisely in this complexity that the lawyer's work in specific cases cannot remain at the mechanical citation of legal provisions or cases, but must return to the essence of the crime involved, re-examine the boundaries of legal application based on behavioral structure, role positioning, and transaction substance, and construct targeted defense paths accordingly.

From the perspective of legal constitutive elements, illegal business operations at least require two core elements:

First, the behavior must have "operational characteristics";

Second, the behavior must be for the purpose of "profit."

The so-called "operational behavior" typically refers to economic activities where the actor continuously provides goods or services externally based on planning, organization, and management, stably participates in market exchanges, and intends to profit from them. In contrast, sporadic, individual transactions are generally difficult to evaluate as "operations" in the criminal law sense.

In the specific context of illegal business operations involving foreign exchange, the distinction between crime and non-crime is generally made as follows:

(1) If the actor meets the following conditions, it should be recognized as a self-use purpose and not as illegal business operations:

Meeting personal needs: earning the price difference from buying and selling virtual currencies, or having a genuine and reasonable demand for foreign exchange.

Profits derived from the price fluctuations of virtual currencies in different markets.

Personal investment or exchange behavior.

Occasional and non-continuous. Transaction counterparties, times, and prices are not fixed.

Funds and virtual currencies circulate unidirectionally in personal accounts as "fiat currency → virtual currency → fiat currency."

(2) If the actor meets the following conditions, it should be recognized as having an operational purpose and suspected of illegal business operations:

Providing financial services: Offering illegal foreign exchange conversion or payment settlement services for profit.

The profit essentially comes from exchange rate differences, fixed handling fees, or commissions.

Engaging in cross-border exchange activities disguised as "foreign currency ↔ virtual currency ↔ RMB" through matched transactions.

Long-term, stable, and organized. Having a fixed customer base or partners, even forming clearly defined groups.

Utilizing (including borrowing) a large number of others' accounts to form a capital pool, achieving matching and hedging of domestic and foreign funds.

For example, in a case represented by Lawyer Shao, a certain U merchant was accused of illegal business operations and detained because, from the perspective of the case handlers, the following characteristics were present:

First, the trading time span is long, the trading frequency is high, and the trading scale is large, with long-term profits earned through buying and selling virtual currencies.

Second, a studio was established, multiple employees were hired, and all employees' bank accounts were used for transactions.

Third, some clients are long-term overseas, the client base is relatively stable, and the transaction amounts are large, all exceeding one million yuan.

From these superficial characteristics alone, it is indeed easy to form an intuitive judgment: this behavior pattern seems to closely align with the typical characteristics of illegal business operations mentioned earlier, and is even quite similar to the situations in existing cases.

However, in reality, the nature of this case is fundamentally different from the aforementioned Lin case:

In the Lin case, the actor was directed by a Nigerian individual and completed the fund flow according to the other's arrangements; the essence of their behavior was to provide cross-border exchange services for others. The virtual currency was merely a tool, and the real purpose was to "assist others in achieving cross-border payment."

In this case, whether the parties involved were "directed by others," "provided payment services for specific clients," "assumed the function of fund transfer," whether the funds constituted a de facto capital pool, and whether client funds were mixed with their own funds… these key issues are precisely where there are significant differences from the Lin case. These differences are the core factors determining the nature of the case, rather than the frequency or amount of transactions themselves.

As pointed out in the analysis by the Shanghai Second Intermediate Court regarding behaviors that do not constitute illegal business operations:

"Currency conversion behaviors linked through U coins are not directly equivalent to foreign exchange trading behaviors, and the actor does not have the subjective intent to assist others in exchanging foreign currency, merely causing the conversion between different currencies objectively";

It should be "combined with the essential characteristics of illegal business operations to substantively judge whether the involved behavior violates national regulations and seriously disrupts the financial market order, to distinguish between crime and non-crime. If the actor uses virtual currency as a medium, bypasses national foreign exchange supervision, provides exchange services between RMB and foreign currencies, and exhibits characteristics of business operations such as earning handling fees or exchange rate differences… it constitutes illegal business operations";

"Comprehensively considering the actor's subjective awareness, objective behavior, profit methods, and other factors, accurately determining whether it constitutes joint crime… if knowingly assisting others in illegal buying or selling or indirectly buying and selling foreign exchange, or conspiring with others in advance… it should be treated as an accomplice to illegal business operations."

Therefore, after Lawyer Shao intervened in this case, he consistently maintained that this case should not be recognized as illegal business operations. The core reasons can be summarized as follows:

First, large-scale, team-based, high-frequency trading does not automatically equate to "operational."

While the parties have long engaged in buying and selling virtual currencies and profiting from price differences, they do have a profit motive, but "profit" and "operational" cannot be simply equated. In the criminal law sense, operational behavior should refer to providing services externally and intervening in the order of fund flow, rather than merely autonomous trading behavior based on market fluctuations.

Second, having a relatively fixed client base does not equate to providing exchange services.

Although the parties have some long-term clients, they have never completed "foreign currency—virtual currency—RMB" or reverse exchange operations according to client instructions. In other words, the parties did not act as a fund transfer channel for others, nor did they substantively provide cross-border payment services; their transactions are still autonomous buying and selling, rather than "acting on behalf of others."

Third, using others' bank cards does not automatically imply a "capital pool" or "underground exchange."

The holders of the bank cards involved in the case are all relatives or acquaintances of the parties, not "cat pool accounts" purchased or illegally collected from the black market. The relevant bank cards have always been under the actual control of the cardholders, and the parties did not engage in buying or renting bank cards. This is distinctly different from typical underground bank operations.

Fourth, the existing evidence cannot form a closed evidence chain and cannot prove subjective knowledge.

The existing evidence neither proves that the parties knew of others' exchange behaviors nor is it sufficient to infer that they "should have known." Under the standard of criminal proof, if subjective intent cannot be proven, a guilty evaluation should not be made.

Fifth, the essence of the behavior is "price difference trading," not "exchange services."

The true purpose of the parties is to utilize price fluctuations between different markets and platforms to earn trading profits through buying low and selling high. Their profits come from market fluctuations themselves, not from earning commissions through matching, payment, or channel services from exchange behaviors. For them, virtual currency is a trading target, not a tool for fund transfer.

It is based on the above facts and evidence structure, while adhering to clear facts and evidence review, that the case was ultimately successfully handled with a "lack of clarity in facts and insufficient evidence" reason for release on bail, achieving a phased result.

This answers the first question posed earlier: how to determine in specific cases whether a certain U merchant's "arbitrage" constitutes legal arbitrage or has already constituted business operations?

Now, the second question: if the profit model of the so-called arbitrage not only derives from exchange rate differences but also includes a certain proportion of "service fees" or "handling fees," does this necessarily constitute illegal business operations?

The core profit source of cross-border virtual currency arbitrage indeed comes from the "exchange rate difference" between different fiat currency zones, rather than the price fluctuations of the virtual currency itself.

However, Lawyer Shao believes that whether it constitutes illegal business operations does not depend on the superficial question of "whether fees are charged," but rather on the essence of the behavior corresponding to the fees charged.

If the actor charges service fees or handling fees beyond the exchange rate difference during the arbitrage process, but does not perform a closed-loop operation of "foreign currency ↔ virtual currency ↔ RMB" according to client needs, using virtual currency for matched exchanges to achieve currency value conversion.

From a legal perspective, this should not constitute illegal business operations, but from a practical standpoint, such behaviors still carry high criminal risks. Due to significant differences in understanding of such cases among different case handlers, there is a possibility of being recognized as illegal business operations. The aforementioned Zhao Dong case's operational model being classified as illegal business operations serves as a warning.

3. Lawyer Shao's Reminder

For U merchants engaged in so-called "arbitrage," this remains a highly risky business. The risks arise not only from the policies themselves but also from the uncertainties in judicial practice—different regions and case handlers often have vastly different understandings of such behaviors, which will directly affect the determination of guilt or innocence and specific sentencing.

Therefore, for U merchants, the so-called "arbitrage" essentially still belongs to a high-risk gray area, and related activities should be cautiously assessed for potential risks, avoiding rash involvement.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。