Original Title: Truth Comes Later

Original Author: Thejaswini M A, Token Dispatch

Original Translation: BitpushNews

Every time the prediction market falls into controversy, we always circle around one question but never truly face it:

Do prediction markets really concern the truth?

Not accuracy, not practicality, and not whether they outperform polls, journalists, or social media trends. But rather, the truth itself.

Prediction markets price events that have yet to occur. They are not reporting facts; they are allocating probabilities for futures that remain open, uncertain, and unknowable. At some point, we began treating these probabilities as a form of truth.

For most of the past year, prediction markets have been basking in their victory tour.

They have beaten polls, outperformed cable news, and surpassed experts with PhDs and PowerPoint presentations. During the 2024 U.S. election cycle, platforms like Polymarket reflected reality faster than all mainstream prediction tools. This success gradually solidified into a narrative: prediction markets are not only accurate but superior—a purer way to aggregate truth, a more authentic signal reflecting people's beliefs.

Then January came.

A brand new account appeared on Polymarket, betting about $30,000 that Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro would be ousted by the end of the month. At that time, the market considered the likelihood of this outcome extremely low—single-digit probability. It looked like a bad trade.

A few hours later, U.S. forces arrested Maduro and brought him to New York to face criminal charges. The account closed, netting over $400,000 in profit.

The market was right.

And that is the crux of the issue.

People often tell a comforting story about prediction markets:

Markets aggregate dispersed information. Those with differing views use money to support their beliefs. As evidence accumulates, prices change. The crowd gradually converges on the truth.

This story assumes an important premise: the information entering the market is public, noisy, and probabilistic—like tightening polls, candidate missteps, storm shifts, or companies missing earnings expectations.

But the Maduro trade was not like that. It was less about reasoning and more about precise timing.

At this moment, prediction markets no longer seem like clever forecasting tools but rather something else: a place where proximity trumps insight, and channels outweigh interpretation.

If the market is accurate because someone possesses information that the rest of the world does not know and cannot know, then the market is not discovering the truth; it is monetizing information asymmetry.

The importance of this distinction far exceeds what the industry is willing to acknowledge.

Accuracy may serve as a warning. Supporters of prediction markets often repeat the same line when faced with criticism: if there were insider trading, the market would react sooner, thus helping others. Insider trading would accelerate the emergence of truth.

This argument sounds clear in theory, but in practice, its logic can self-destruct.

If a market becomes accurate because it contains leaked military actions, classified intelligence, or internal government timelines, then it is no longer an information market on any publicly meaningful level. It becomes a shadowy place for secret trading. There is an essential difference between rewarding superior analysis and rewarding proximity to power. Markets that blur this line will ultimately attract regulatory scrutiny—not because they are not accurate, but precisely because they are overly precise in the wrong way.

Voron23 @0xVoron Confirmed insider wallets on Polymarket.

"They made over a million dollars daily on the Maduro event. I've seen this pattern too many times, without a doubt: insiders always win. Polymarket just makes it easier, faster, and more visible. Wallet 0x31a5 turned $34,000 into $410,000 in 3 hours."

The unsettling aspect of the Maduro event lies not only in the scale of the returns but also in the context in which these markets erupted.

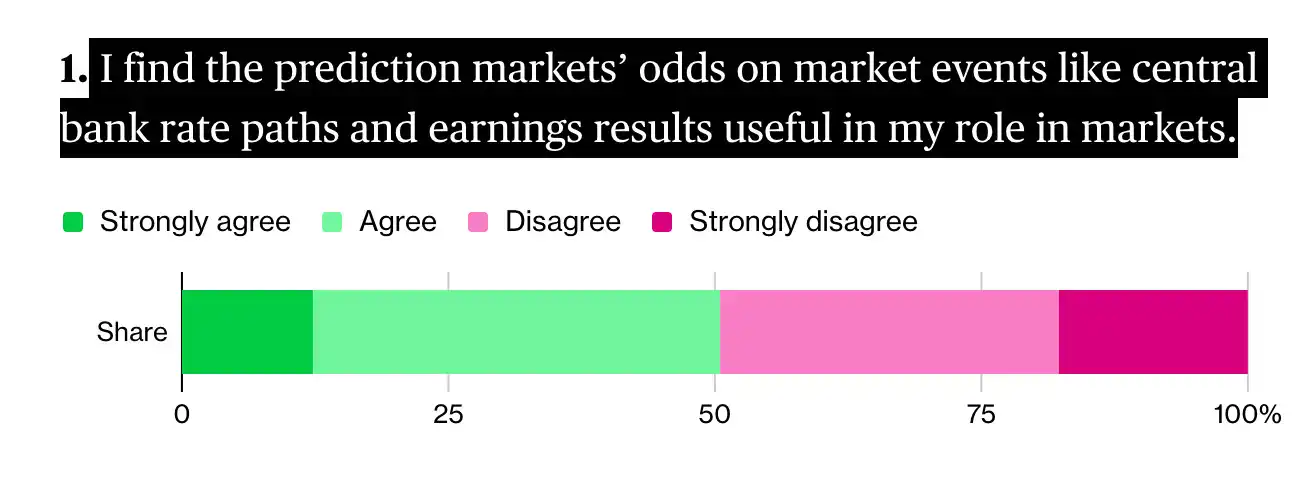

Prediction markets have evolved from a fringe novelty into an independent financing ecosystem that Wall Street takes seriously. According to a Bloomberg survey from last December, traditional traders and financial institutions view prediction markets as a financial product with lasting viability, although they also acknowledge that these platforms expose the gray area between gambling and investing.

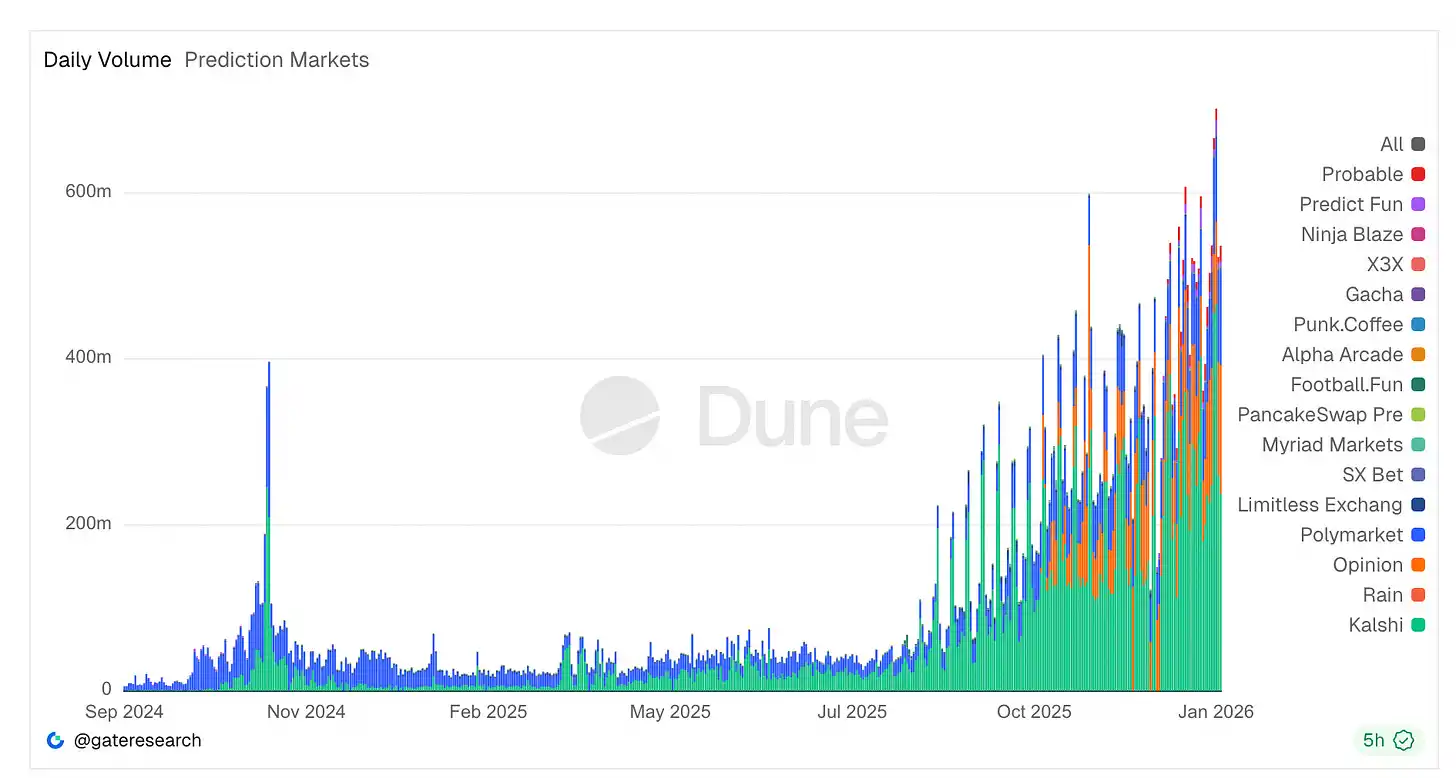

Trading volume has surged. Platforms like Kalshi and Polymarket now have annual nominal trading volumes in the billions—Kalshi alone processed nearly $24 billion in 2025, with political and sports contracts attracting liquidity on an unprecedented scale, continuously breaking daily trading records.

Despite scrutiny, daily trading activity in prediction markets has reached historic highs, around $700 million. Regulated platforms like Kalshi dominate trading volume, while crypto-native platforms maintain cultural relevance. New terminals, aggregators, and analytical tools are emerging weekly.

This growth has also attracted the interest of heavyweight financial capital. The owner of the New York Stock Exchange has committed to providing Polymarket with up to $2 billion in strategic investment, valuing it at around $9 billion, marking Wall Street's belief that these markets can compete with traditional trading venues.

However, this excitement is colliding with regulatory and ethical ambiguities. Polymarket was banned early on for operating without registration and paid a $1.4 million CFTC fine, only recently regaining conditional approval in the U.S. Meanwhile, legislators like Congressman Ritchie Torres have introduced specific bills aimed at prohibiting government insiders from trading in the aftermath of the Maduro event, arguing that the timing of these bets resembles insider trading opportunities rather than informed speculation.

Yet, despite facing legal, political, and reputational pressures, market participation has not declined. In fact, prediction markets are expanding from sports betting into more areas like corporate earnings metrics, with traditional gambling companies and hedge fund departments now arranging experts to engage in arbitrage and price inefficient trades.

In summary, these developments indicate that prediction markets are no longer on the fringes. They are deepening their ties to financial infrastructure, attracting professional capital, and prompting the creation of new laws, while their core operational mechanism remains fundamentally a bet on uncertain futures.

Overlooked Warning: The Zelensky Suit Incident

If the Maduro event exposed insider issues, the Zelensky suit market revealed deeper problems.

In mid-2025, Polymarket opened a market betting on whether Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky would wear a suit before July. It attracted massive trading volume—hundreds of millions of dollars. What seemed like a joke market evolved into a governance crisis.

Zelensky appeared in a black jacket and trousers designed by a well-known menswear designer. The media called it a suit, and fashion experts also referred to it as a suit. Anyone with eyes could see what was happening.

But the oracle vote determined: not a suit.

Why?

The reason is that a few large token holders bet significant amounts on the opposite outcome, while they held enough voting power to push through a resolution favorable to themselves. The cost of bribing the oracle was even lower than the potential payout they could receive.

This is not a failure of the decentralized ideal but a failure of incentive design. The system operated entirely according to preset rules—human-led oracles whose honesty depended entirely on the "cost of lying." In this case, lying was clearly more profitable.

It is easy to view these events as extreme cases, growing pains, or temporary glitches on the road to a more perfect prediction system. But I believe this interpretation is misguided. These are not coincidences but the inevitable result of three combined factors: financial incentives, ambiguous rule statements, and underdeveloped governance mechanisms.

Prediction markets do not discover the truth; they merely reach a settlement.

What matters is not what most people believe but what the system ultimately recognizes as a valid outcome. This recognition process often lies at the intersection of semantic interpretation, power struggles, and financial games. And when significant interests are involved, this intersection quickly fills with various forces.

Once you understand this, such controversies no longer seem surprising.

Regulation Does Not Arise from Thin Air

The legislative response to the Maduro trade is predictable. A bill currently advancing in Congress would prohibit federal officials and staff from trading in political prediction markets when they possess significant non-public information. This is not radical; it is just basic rules.

The stock market figured this out decades ago. Government officials should not profit from the privilege of accessing state power—this view is uncontroversial. Prediction markets are only now discovering this because they have long insisted on pretending to be something else.

I believe we have overcomplicated this matter.

Prediction markets are places where people bet on outcomes that have yet to occur. If events unfold in the direction they bet on, they make money; if not, they lose money. Any other description we provide is secondary.

It does not become something else simply because the interface is cleaner or the odds are expressed in probabilities. It also does not become more serious because it operates on a blockchain or because economists find the data interesting.

What matters are the incentives. You are rewarded not for your insight but for correctly predicting what will happen next.

I think it is unnecessary for us to keep insisting on framing this activity as something more noble. Calling it prediction or information discovery does not change the risks you bear or the reasons you bear them.

To some extent, we seem reluctant to admit: people just want to bet on the future.

Yes, they do. There is nothing wrong with that.

But we should no longer pretend it is something else.

The growth of prediction markets fundamentally stems from people's demand to bet on "narratives"—whether elections, wars, cultural events, or reality itself. This demand is real and enduring.

Institutions use it to hedge against uncertainty, retail investors use it to express beliefs or for entertainment, and the media sees it as a barometer. None of this requires dressing the activity in any finery.

In fact, it is this disguise that creates friction.

When platforms brand themselves as "truth machines" and occupy the moral high ground, every controversy feels like a life-and-death crisis. When the market settles in a disconcerting way, the event is elevated to a philosophical dilemma rather than its essence—a dispute about settlement methods in a high-risk betting product.

The misalignment of expectations stems from the dishonesty of the narrative itself.

I am not against prediction markets.

They are one of the relatively honest ways for humans to express beliefs in uncertainty, often surfacing unsettling signals faster than polls. They will continue to grow.

But if we beautify them into something more exalted, we are being irresponsible to ourselves. They are not epistemological engines but financial tools linked to future events. Recognizing this distinction can make them healthier—clearer regulation, more explicit ethics, and more reasonable designs will unfold as a result.

Once you acknowledge that you are operating a betting product, you will no longer be surprised by the occurrence of betting behavior within it.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。