Written by: Sleepy.txt, Kaori, Dongcha Beating

On January 22, 2026, Capital One announced its acquisition of Brex for $5.15 billion. This unexpected deal saw Silicon Valley's youngest unicorn being acquired by Wall Street's oldest bankers.

Who is Brex? The hottest corporate payment card company in Silicon Valley. Two Brazilian prodigies founded Brex at the age of 20, achieving a valuation of $1 billion in just one year and reaching $100 million in ARR within 18 months. By 2021, Brex was valued at $12.3 billion and was hailed as the future of corporate payments, serving over 25,000 companies, including star firms like Anthropic, Robinhood, TikTok, Coinbase, and Notion.

Who is Capital One? The sixth-largest bank in the U.S., with assets of $470 billion and deposits of $330 billion, ranking third in credit card issuance nationwide. Founder Richard Fairbank, now 74, established Capital One in 1988, spending 38 years building it into a financial empire. In 2025, he completed a $35.3 billion acquisition of the credit card lender Discover, one of the largest mergers in the U.S. financial industry in recent years.

These two companies represent the speed and innovation of Silicon Valley and the capital and patience of Wall Street.

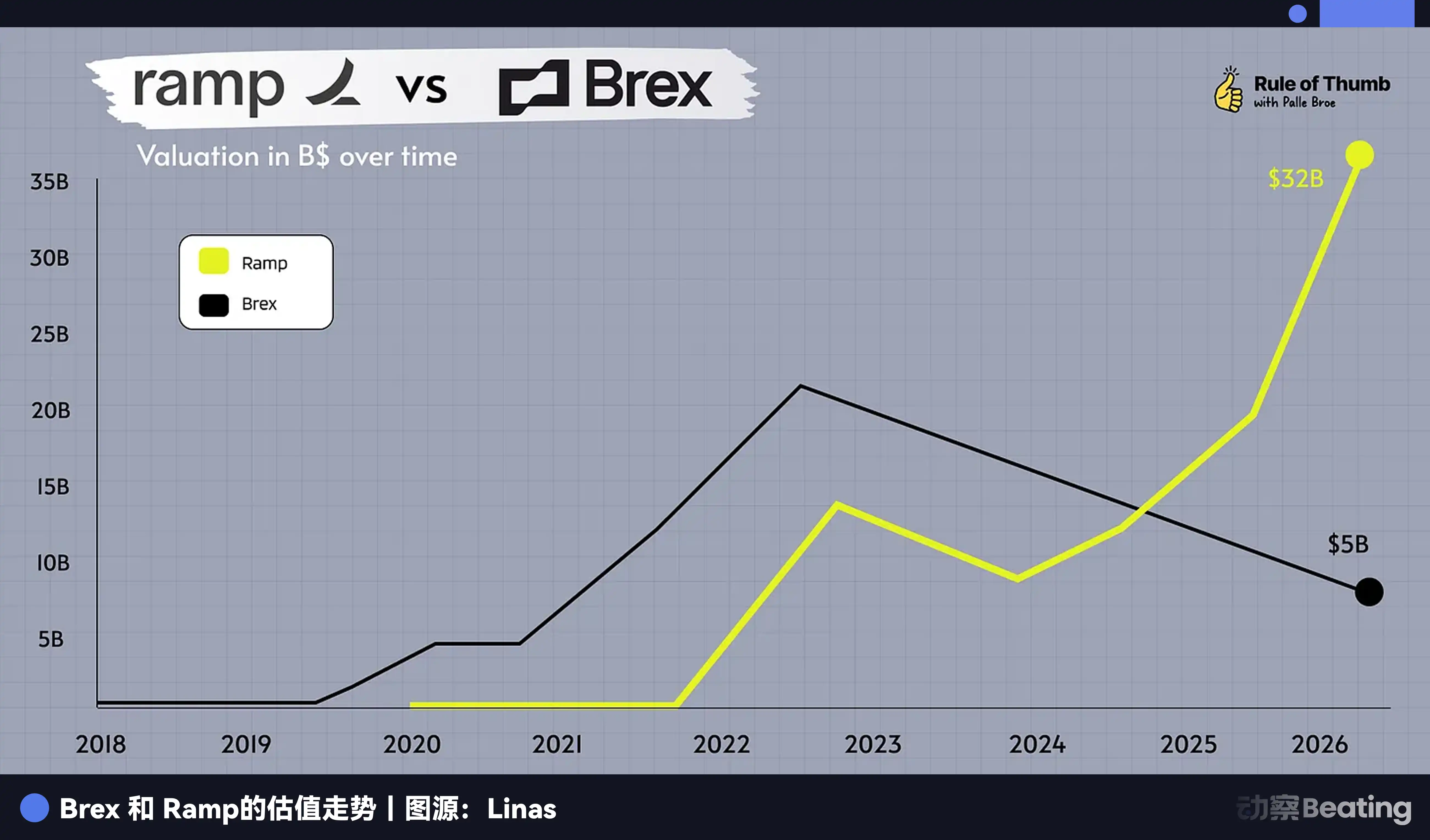

However, behind a string of data lies a paradox: Brex is still growing at a rate of 40-50%, with an ARR of $500 million and over 25,000 customers. Why would such a company choose to sell, and at a price 58% lower than its peak valuation?

The Brex team claims it is to accelerate and scale, but accelerate what? Why now? Why Capital One?

The answer to this paradox lies in a deeper question. What does time mean in the financial industry?

Brex Had No Choice

After the acquisition announcement, many lamented that Brex did not choose to go public. However, in the eyes of the Brex team, this deal came at just the right time.

Before engaging with Capital One, Brex's leadership had focused on continuing to raise private funding, preparing for an IPO, and operating as an independent company.

The turning point occurred in the fourth quarter of 2025. Brex CEO Pedro Franceschi was introduced to Fairbank, the banking giant who has led Capital One for over 38 years, and he dismantled Pedro's resolve with a simple logic.

Fairbank laid out Capital One's balance sheet: $470 billion in assets, $330 billion in deposits, and the third-largest credit card distribution network in the U.S. In contrast, while Brex boasts the smoothest software interface and risk control algorithms, its cost of capital has always been constrained.

In the world of Fintech, growth was once the only currency, but by 2026, Fintech companies were facing changes in the capital market environment, a reassessment of growth expectations, and an accelerating wave of mergers and acquisitions in the financial services industry.

According to Caplight data, Brex's current valuation in the secondary market is only $3.9 billion. Brex CFO Dorfman mentioned a key detail in the post-acquisition review: "The board believes that a 13x gross profit acquisition multiple aligns with the premium standards of top public companies."

This statement implies that if Brex chose to go public, under the market conditions at the beginning of 2026, a Fintech company growing at 40% and not yet fully profitable would find it extremely difficult to achieve a valuation multiple exceeding 10x in the public market. Thus, even with a successful IPO, Brex's market value would likely fall below $5 billion, facing the risk of long-term liquidity discounts.

On one side is an extremely uncertain path to going public, with the potential for a post-IPO drop and short-seller attacks; on the other side is the cash and stock combination offered by Capital One, along with the immediate backing of a large bank's credit.

If it were merely a matter of valuation fluctuations, could Brex choose to optimize its software and algorithms to weather the capital winter? Reality did not provide Brex with that option.

The Balance Sheet Consumes the World

For a long time, Silicon Valley has adhered to A16Z's famous saying, "Software is eating the world."

The founders of Brex are staunch believers in this creed, but the financial industry harbors an iron law that software engineers find difficult to comprehend: in the war of currencies, user experience is merely a facade; the balance sheet is the true operating system.

As a Fintech company without a banking license, Brex is essentially a shell bank. Every credit it extends relies on funding support from partner banks, and the interest income from deposits must be shared with the banks providing account support.

This was not an issue in the low-interest-rate era, as capital was abundant. But in a high-interest environment, Brex's business model began to suffocate.

We can break down Brex's revenue structure: by 2023, about one-third of its revenue came from the interest margin on customer deposits, approximately 6% from SaaS subscription fees, and the remainder from credit card transaction fees.

When interest rates remain at 5.5%, Brex faces a dilemma of being squeezed from both ends.

On one hand, high funding costs mean customers are no longer willing to leave millions of dollars idle in a Brex account that earns no interest; they demand higher returns, directly cutting into Brex's interest margin.

On the other hand, the risk weight is rising, and in a high-interest environment, the risk of startup failures increases exponentially. Brex's proud real-time risk control system had to become conservative, drastically cutting credit limits, which led to a significant slowdown in transaction growth.

Fairbank made a subtle yet sharp remark in the acquisition announcement: "We look forward to combining Brex's leading customer experience with Capital One's strong balance sheet." This translates to: your code is beautifully written, but you don't have enough cheap money.

Capital One has $330 billion in low-cost deposits, meaning that for the same $100 loan to a business, Capital One's profitability could be more than three times that of Brex.

Software can change the experience, but capital can buy the experience; this is the harsh reality of the Fintech industry in 2026. The software system that Brex took nine years and $1.3 billion in funding to build is merely a plugin that can be integrated in the face of Capital One's substantial capital.

But there is also an ultimate question: why couldn't Brex wait patiently for the next interest rate cycle like Capital One? They are not yet 30, with successful track records and ample personal wealth, and could easily sustain the company. What led them to ultimately choose surrender?

29 Years Can't Wait, 74 Years Can

Because in the financial industry, time is not a friend; it is an enemy. And only capital can turn enemies into friends.

Henrique Dubugras and Pedro Franceschi's careers are almost an epic tale of speed. They started their first business at 16 and sold it three years later. They launched a second venture at 20 and became a unicorn in two years. They are accustomed to measuring success in years, or even months. For them, waiting 5 to 10 years is nearly the length of an entire career.

They believe in speed, rapid trial and error, quick iteration, and fast success. This is the creed of Silicon Valley and the biological clock of 20-year-olds.

But their opponent is Richard Fairbank.

Fairbank, now 74, founded Capital One in 1988 and spent 38 years building it into the sixth-largest bank in the U.S. He does not believe in speed; he believes in patience. In 2024, he spent $35.3 billion to acquire Discover, taking over a year to integrate. In 2026, he spent $5.15 billion to acquire Brex, stating that they could take 10 years to integrate.

These are two completely different time structures.

20-year-old Dubugras and Franceschi measure their time with investors' money. Brex raised $1.3 billion, and investors expect returns within 5 to 10 years, either through an IPO or an acquisition.

Although this acquisition was not driven by investors, the need for investor exits was indeed a factor Pedro had to consider in his decision-making. CFO Dorfman repeatedly emphasized providing 100% liquidity for shareholders, which is not coincidental.

More importantly, the founders' own time is also limited. Pedro is 29 this year; he can wait 5 years or 10 years, but can he wait 20 years? Can he, like Fairbank, spend 38 years slowly refining a company? With competitors like Ramp already surpassing them, the IPO window uncertain, and investors needing an exit, Pedro's time is also running out.

At 74, Fairbank's time is bought with depositors' money. Capital One has $330 billion in deposits; although depositors can theoretically withdraw at any time, statistically, deposits are a relatively stable source of funding. Fairbank can afford to wait 5 years, 10 years, until interest rates drop, until Fintech valuations hit rock bottom, until the best acquisition opportunity arises.

This is the inequality of time. Fintech's time is limited, whether for founders or investors; banks' time is relatively infinite because deposits are a relatively stable source of funding.

Brex's story serves as a lesson for all Fintech entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley: no matter how fast you are, you cannot outpace the patience of capital.

The Fate of Innovators

Brex's acquisition marks the end of an era, the romantic era that believed Fintech could completely replace traditional banks.

Looking back over the past two years, in April 2025, American Express acquired expense management software Center. In September 2025, Goldman Sachs, after cutting its consumer finance business, turned around and acquired an AI lending startup based in Boston. In January 2026, JPMorgan completed the integration of the UK pension technology platform WealthOS.

It can be said that Fintech companies are responsible for charging ahead in the 0 to 1 stage, using venture capital subsidies for market trial and error, user education, and technological innovation. Once the business model is validated, or the industry enters a downturn leading to a valuation correction, traditional banks emerge like scavengers, harvesting the fruits of these innovations at a lower cost.

Brex burned through $1.3 billion in funding, accumulating 25,000 of the highest-quality startup clients and assembling a world-class financial engineering team. Now, Capital One only needs to pay $5.15 billion, a significant portion of which is in stock, to take over all of this.

From this perspective, Fintech entrepreneurs are not disrupting banks; they are working for them. This is a new model of risk outsourcing, where traditional banks no longer need to engage in high-risk R&D internally; they just need to wait.

Brex's exit has shifted all the spotlight onto its competitor, Ramp.

As the only super unicorn currently in the field, Ramp still appears strong. Its ARR continues to grow, and its balance sheet seems more robust. But its time is also running out.

Founded in 2019, Ramp has now entered its seventh year, a point at which VC investors typically expect accountability. Late-stage investors entered in 2021-2022 with valuations exceeding $30 billion, and their return expectations will far exceed those of Brex.

If the IPO window in 2026 remains open only to a select few profitable giants, will Ramp face the same choice?

History does not simply repeat itself, but it always rhymes. The story of Brex tells us that in the ancient industry of finance, there is no such thing as a purely software company. When external conditions change dramatically, the time disadvantage of Fintechs becomes exposed, and they must choose between being acquired and long-term struggle. Pedro chose the former; this is not surrender, but clarity.

Yet this clarity itself is the fate of Fintech.

Just don't forget that Brex once claimed it would disrupt American Express, even setting the Wi-Fi password in one of its offices to "BuyAmex."

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。