Written by: Tantu Macro

- There has been much discussion in the market regarding Warsh's new appointment, with a consensus emerging around more interest rate cuts and more balance sheet reduction. However, we believe that neither the interest rate policy (rate cuts) nor the balance sheet policy (balance sheet reduction) will significantly impact the existing policy path under Warsh in 2026.

2. First, regarding the balance sheet policy: Currently, there are no objective conditions in the U.S. money market for more or faster balance sheet reduction.

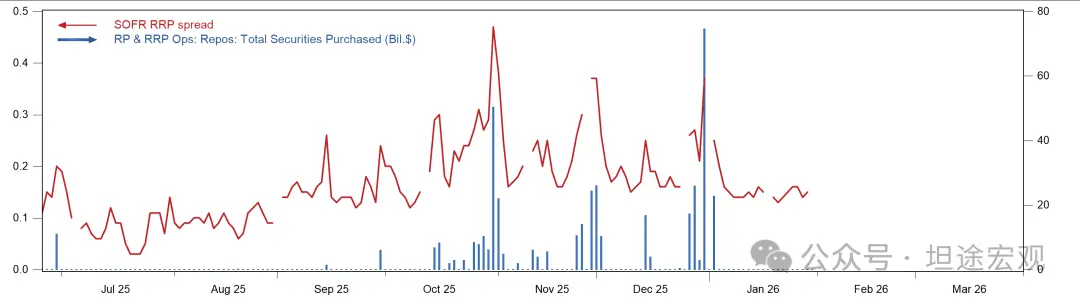

1) After the fourth quarter of 2025, the usage of ONRRP has basically dropped to zero, the SOFR-ONRRP spread has risen to a historical high of 25bps, and the usage of SRF has also remained above zero. These signals indicate that the liquidity situation in the U.S. interbank market has shifted from abundant to just above ample. Demand for overnight funding from dealer banks, hedge funds, and other parties has encountered difficulties in financing and high costs. This is also why the Fed decided to restart technical balance sheet expansion (RMP) last December (Figure 1).

Figure 1: SOFR-ONRRP Spread vs. SRF Usage

2) In this situation, abruptly stopping RMP and restarting balance sheet reduction would, on one hand, trigger a liquidity "crisis" in the repo market and a surge in SOFR, and on the other hand, lead to a significant increase in SRF usage, effectively resulting in no actual balance sheet reduction (when dealer banks use SRF, the Fed is passively expanding its balance sheet). In other words, forcibly reducing the balance sheet in the current environment would not produce any substantial effects aside from causing liquidity issues in the repo market.

3) For the U.S. interbank market to continue reducing the balance sheet, or even return to a "scarce reserves framework," it would require a complete overhaul of the existing banking regulatory framework, including but not limited to Basel 3 (LCR), the Dodd-Frank Act (stress tests, RLAP), and even the self-regulatory constraints that banks have developed over the past 20 years (LoLCR). This is far beyond the authority of the Fed Chair (Dodd-Frank requires Congress, and internal banking regulatory habits require slow adjustments from large banks).

4) The only thing Warsh can do at this point is to try to persuade the FOMC to reduce the monthly purchase amount of RMP or to pause RMP during a future phase when TGA declines significantly and reserves rebound quickly. However, like any Fed voting member, avoiding a liquidity crisis in the repo market is a prerequisite for Warsh advocating for a slowdown in RMP. Considering that RMP is a policy approved by a unanimous vote of the FOMC, the likelihood of significant rewrites is low.

5) The potential impact may come during the next recession/crisis. If the Fed has already reached the ZLB but liquidity pressures remain severe and the economic recovery outlook is still bleak, Warsh may be more inclined to end QE sooner or start QT earlier. However, this highly depends on the depth of the crisis at that time and Warsh's own mindset (which differs significantly between those in power and observers), as well as whether he is pragmatic enough. We need more time to observe him.

3. Second, regarding interest rate policy: Warsh is unlikely to significantly change the existing interest rate path outlook.

1) The threshold for Warsh to turn hawkish is quite high. Currently, the U.S. labor market remains in a "no jobs, no layoffs" frozen state, and inflation data is still slowly progressing towards 2%. Coupled with the likelihood that he will need to "thank" Trump, it is unlikely that he will make a noticeable hawkish turn in 2026.

2) The threshold for Warsh to turn dovish (for example, cutting rates more than three times without significant changes in growth and inflation data) is also quite high. On one hand, current interest rates are indeed near neutral, and the Fed is qualified to "wait and see," without rushing to cut rates. On the other hand, the unemployment rate is the most important indicator for the FOMC in 2026, as seen in the past three economic forecasts (SEP), where the FOMC has consistently maintained its unemployment rate forecast for 2026 at 4.4-4.5%, indicating that the unemployment rate will be the FOMC's "soft target" in 2026. If the unemployment rate does not significantly exceed 4.5% in Q4 of 2026, the likelihood of persuading other voting members to support significant rate cuts is low.

3) Historically, any new Fed Chair too closely aligned with the president faces strict scrutiny from other voting members, and any "foolish" actions will result in a significant number of opposing votes. A case in point is G. William Miller, the shortest-serving Fed Chair from 1978-1979, who was an ally of President Carter and insisted on not raising rates in a high-inflation environment, ultimately facing a barrage from FOMC members and being reassigned by Carter.

4) There are two scenarios where Warsh might unexpectedly cut rates significantly. One is if the risk of recession increases significantly or if stock prices plummet. The other is if inflation significantly declines in 2026. Currently, the former scenario seems unlikely, but if Trump cancels tariffs in the second half of the year (in a push for midterm elections), a temporary decline in commodity CPI could provide Warsh's Fed with a brief window (excuse) for rate cuts.

4. Third, regarding the policy framework: Warsh may lack the flexibility and pragmatism compared to Powell.

1) Warsh has repeatedly expressed opposition to data dependence and forward guidance, emphasizing trend dependence rather than data dependence. He believes that the Fed should only adjust monetary policy when deviations from employment and inflation targets are "clear and significant," rather than responding to monthly reports (such as employment data), as monthly data is noisy and easily subject to revision. He argues that the Fed should prioritize medium- to long-term economic trends over immediate data points, basing monetary policy on judgments about future economic cycle trends rather than recent economic data.

2) This approach is in stark contrast to Powell's. Powell is known for his flexibility and pragmatism, as seen in his pivot after the market crash in Q4 2018, the unprecedented market rescue in March 2020, the decision to raise rates by 75bps during the blackout period in June 2022, and the decision to cut rates by 50bps based on a single employment data point in September 2024.

3) If Warsh's policy philosophy is indeed as he has previously advocated, then his monetary policy will be more "rigid" and "subjective," objectively amplifying the volatility of the macroeconomy and the market.

In summary, it is expected that Warsh will not be able to immediately implement the policy proposals of rate cuts and balance sheet reduction after taking office; he needs to coordinate with the economic inflation environment and the positions of FOMC voting members while maintaining his relationship with Trump as much as possible. For the market, whether Warsh is a sufficiently pragmatic, independent, and professional new Fed Chair will require a longer observation period.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。