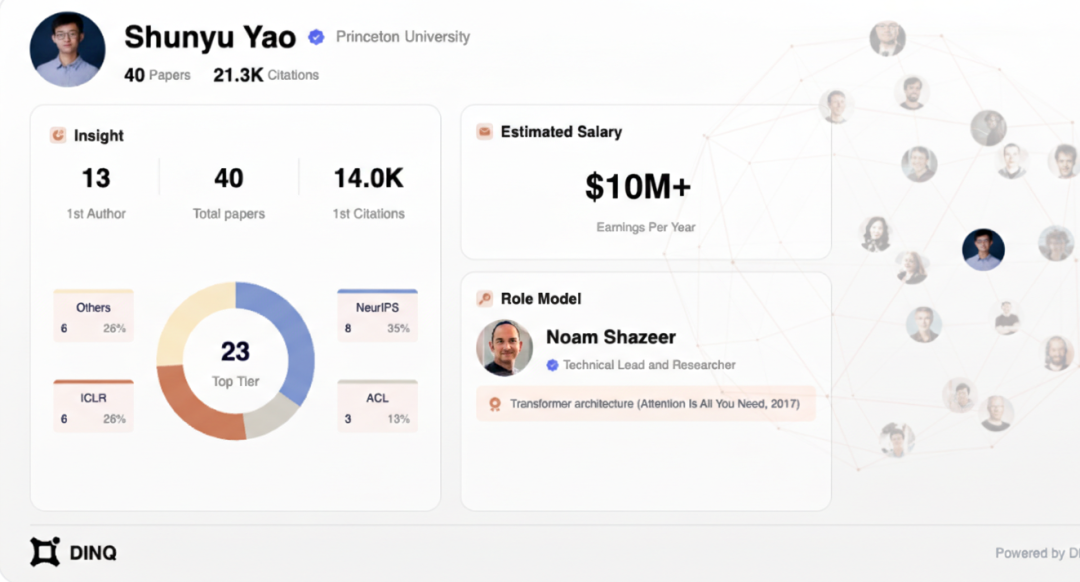

After testing my worth on DINQ, I was devastated. Yao Shunyu is valued at 10 million dollars, while I am only worth a 1000 yuan base salary.

In the AI circle, if you haven't been "humiliated" by DINQ yet, you might not have truly entered the circle.

The way this product became popular is extremely "outrageous": it not only offers enticing offers to talents but also comes with a brutally honest "AI spicy review" feature. As long as you dare to throw in your GitHub link or Google Scholar homepage, the AI will transform into a foul-mouthed interviewer, accurately firing at your citation count and code contributions.

By analyzing Yao Shunyu's papers, citations, work experience, and educational background, DINQ provided a predicted salary of 10 million dollars.

This "seeking to be scolded" self-deprecating mentality unexpectedly unified the social front of researchers worldwide. From Stanford's laboratories to Silicon Valley's cafes, people are everywhere sharing screenshots of their worth. When Yao Shunyu was measured at a value of 10 million dollars and was brought out to compete with another individual, this small team of only 8 people, which had just received millions of dollars in investment from BlueRun, had quietly infiltrated the social radar of top AI talents globally.

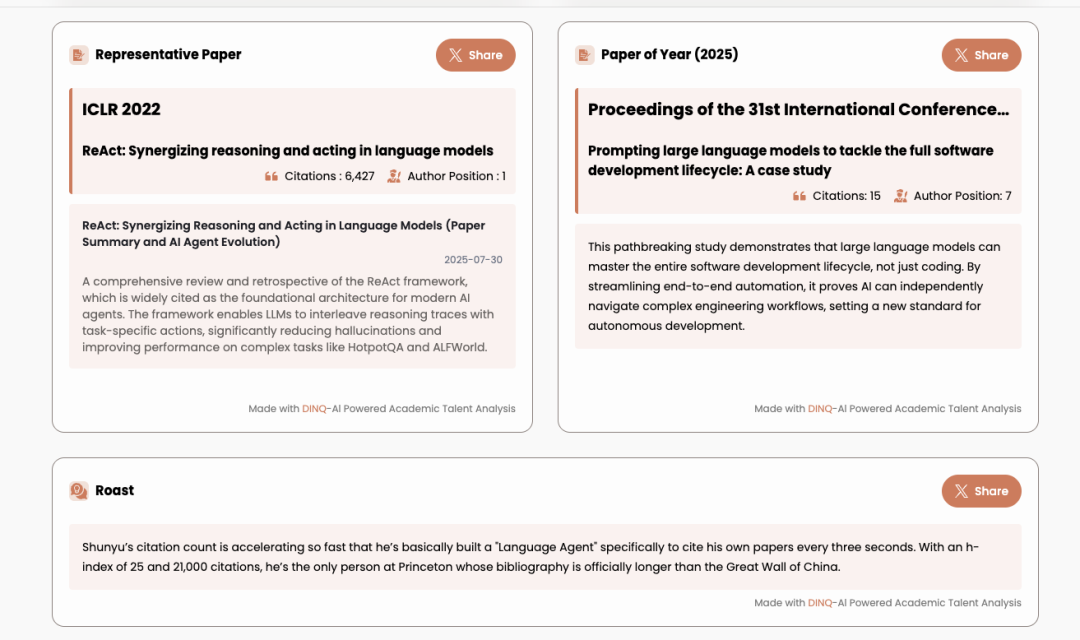

Mocking academic rising stars, spicy reviews of Yao Shunyu.

"Shunyu's citation growth rate is faster than a rocket; he probably wrote a 'language agent' that automatically cites his papers every three seconds. With an H-index of 25 and 21,000 citations, he has become the only person at Princeton whose reference list is longer than the Great Wall."

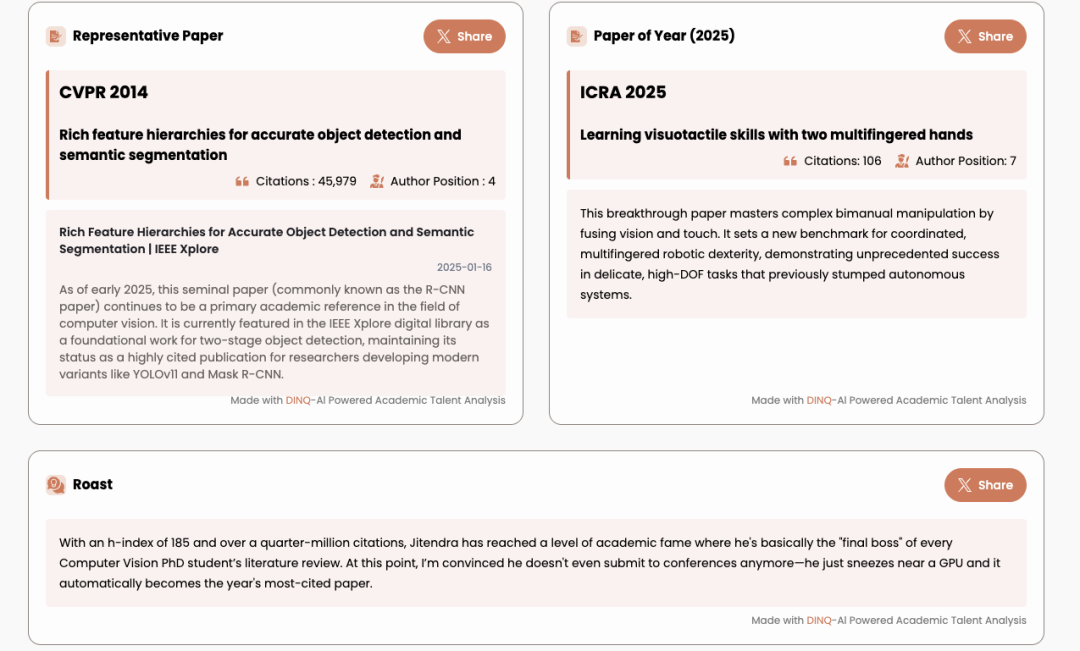

Mocking academic giant Jitendra Malik.

"With an H-index of 185 and over 250,000 citations, Jitendra has reached the pinnacle of academic fame—he is basically the 'ultimate BOSS' in every computer vision PhD student's literature review. I even suspect he doesn't need to submit papers anymore; he just has to sneeze next to a GPU, and a top-cited paper will automatically pop out."

Spicy review of cross-industry mogul Bill Gates.

"Bill Gates, huh? The only one who can turn a window-selling mistake into a billion-dollar business! As 'CEO', you have mastered the art of making people believe you are genuine while cleverly avoiding all software updates. Remember, mate, in Australia, even kangaroos want to jump over your 'legacy'!"

While it's all in good fun, many big names joined DINQ during the beta phase, including various researchers from OpenAI. Many even actively recommended DINQ on X.

But behind the jokes, DINQ is doing something quite serious.

According to founders Sam and Kelvin, the keyword-matching search model of LinkedIn has become "outdated" in the AI era. The true AI experts are often "invisible": they don't submit resumes, don't mingle in workplace social circles, and their essence is scattered across papers on arXiv, projects on Hugging Face, and even late-night rants on Twitter.

DINQ's logic is: since you don't show up, I'll use AI Agents to "human flesh" you like a detective. It is no longer a rigid census but has the ability to understand the boundaries of technology. Even if an HR's requirement is vague, like "find a young person who can solve character consistency in video generation," the Agent can instantly pull out that "underwater" genius who has never appeared in the talent market from the fragmented traces across the internet.

In this nearly 20,000-word in-depth conversation, they discussed not only how to help big companies recruit but also how to create a DINQ Card for millions of AI developers worldwide through the technical philosophy of "Less Structure, More Intelligence."

A radical transformation of an architecture graduate, opening the door to Damo Academy through self-study

Jane: Please introduce yourself and your company in one sentence.

Gao Daiheng Sam: DINQ is a talent intelligence platform for AI developers, researchers, and creators. We help them be discovered and connected to world-class opportunities more efficiently by automating the analysis of their real achievements and influence. As for me personally, I am the first algorithm engineer to enter Alibaba's Damo Academy (later Tongyi Lab) through open-source contributions.

Jane: I see from your resume that you initially didn't major in computer science? When did you decide to switch tracks? After all, your later career has revolved around this core.

Gao Daiheng Sam: Yes, I actually studied architecture for my undergraduate degree. I truly realized and actively shifted to computer science in 2017. There was a very clear historical context at that time—China was in the first wave of a fervent AI startup boom. On one hand, opportunities were very concentrated, and on the other hand, the learning resources available online had become sufficiently rich for the first time, making it possible for "non-technical majors to transition into AI."

But for me personally, the more essential reason was that I had clearly felt that my original development path was not going well. At that time, I was studying for my master's degree at Beijing University of Technology, and if I continued down that path, it would be very difficult to find a job in Beijing with a monthly salary of around 10,000 yuan, often accompanied by extremely high intensity and long-term unsustainable overtime.

At the same time, I was also able to access some internal industry judgments; many people were discussing that the development structure at that time was actually unhealthy, especially the long-term expectations related to real estate were not optimistic. Against this backdrop, I began to ask myself a question early on: if this path is destined to "GG," should I proactively jump out?

So ultimately, I combined my judgment of the era's trends with my reflection on my own situation and made a relatively radical but rational choice—to systematically self-study AI and computer-related courses online, which became the starting point for everything that followed.

Jane: What was your entry point when transitioning to the computer field?

Gao Daiheng Sam: Mainly through Andrew Ng's online courses for systematic learning. I feel that this industry essentially doesn't have textbooks; everyone is learning based on existing materials. So in this industry, your background and origins are not that important; rather, your interest in the field is more crucial.

Jane: Let's talk about that highly recognized project in your career, the one you did during your time at Alibaba's Damo Academy? But I want to confirm, was going to Alibaba your second job after deciding to delve into AI and algorithms?

Gao Daiheng Sam: First, let me clarify that this project was not done at Alibaba. Alibaba was my second job. Let me explain the context: after graduating in 2018, I had actually been working on open-source projects even before graduation. Initially, I was writing code for deep learning frameworks like TensorFlow.

But at that time, I discovered a problem: when I worked on such low-level things, very few people could understand "this is what you did" or "what exactly you did." In that era, it was hard to be understood; but there were also benefits, for example, because I had these contributions, domestic teams like OneFlow led by Yuan Jinhui would know about me. At that time, there were not many people who had more than ten PRs on TensorFlow and PyTorch and were working in mainland China.

Then I thought about a question: can I do something less low-level and more visually understandable, so that people can see at a glance what I am doing, and I don't need to spend effort explaining? Because I had a background in art, I thought that working on images or videos might make it easier for others to understand what I was doing.

So after graduation, I initially went to a small company. While working there, I was basically doing open-source projects every day—DeepFaceLab was also developed during that phase.

Jane: This project received excellent feedback later. Were you working solo, or was there a team involved?

Gao Daiheng Sam: It was actually a multinational open-source collaboration project. I remember it ranked second in influence that year, only behind TensorFlow.

Jane: With such a high-impact project, did you ever consider submitting it to a top conference?

Gao Daiheng Sam: I did submit it, but it was rejected. The reason was that the content was highly controversial and sensitive at the time, and the academic community didn't dare to take that risk. Later, I didn't dwell on it and directly published it on arXiv.

Jane: Did the positive feedback from this project strengthen your confidence in choosing Damo Academy later? Why didn't you consider big companies like Meta or ByteDance?

Gao Daiheng Sam: The core reason is that Damo Academy allowed me to continue delving into video. At that time, the offer from Meta was for the "Red Team," mainly responsible for defensive content review, dealing with a large amount of negative audiovisual material daily, which I felt wasn't good for my mental and physical health. Meanwhile, ByteDance was more focused on audio and video encoding, which was not closely related to my research field.

Jane: Damo Academy indeed leans more towards cutting-edge technology research. You worked on many digital human projects there; can you share that experience and the insights it brought you?

Gao Daiheng Sam: During my two to three years at Damo Academy, we made many attempts from technology to implementation. For example, during the 2022 Year of the Tiger Spring Festival Gala, my colleagues and I developed a 3D digital tiger that appeared on the live broadcast of the CCTV online Spring Festival Gala. Later, I also participated in the 3D digital human project for the Winter Olympics. In the later stages, I shifted to image generation based on diffusion models, with the most successful project being the virtual fitting project Outfit Anyone. This project currently generates one to two hundred million yuan in revenue for Alibaba Cloud each year.

Jane: During your time at Damo Academy, you witnessed the industry's huge changes before and after the explosion of ChatGPT. What was the atmosphere like internally? I've heard from friends at Alibaba that the status of large models within domestic big companies seemed a bit subtle. For example, during the 2021 and 2022 Yunqi Conference, it seemed that Teacher Yang Hongxia was not originally the first choice to talk about large models and was a last-minute replacement. I'm objectively curious about the real changes you felt internally.

Gao Daiheng Sam: Indeed, but first, I should clarify that our team is not in the same sequence as theirs (Teacher Yang Hongxia's team); they are more focused on text-based large models. I joined the company in 2020, and researchers like Luo Fuli and Lin Junyang, who later became very active in the large model field, also joined around that time. I have many "Alibaba Star" friends, so I am quite familiar with the situation back then.

In fact, regarding the value of large models and talent, some of Zuckerberg's actions this year have essentially "sealed the deal" (given a definitive conclusion). You can see that now, big companies are willing to spend heavily to recruit those young people who have truly developed core technologies.

Jane: Indeed, the technical discourse is returning to the hands of young people.

Gao Daiheng Sam: Exactly. I find the logic behind this very interesting—many research results were originally scattered across various communities and papers, but now everyone is starting to realize that whoever can gather these scattered results and achieve breakthroughs is the core.

Jane: Let's return to the mechanisms at Damo Academy: if you had an idea to implement, what was the internal process like? Were the assessment metrics based on papers or business value?

Gao Daiheng Sam: The internal process at Damo Academy was very "bottom-up." The team leader would usually only define a macro research direction, and the rest was up to us to explore. The management was very flat, with basically no granular constraints. If you needed resources—whether it was computing power, data labeling, or interns—you could apply for them.

During the 2021 and 2022 period, everyone was still in an exploratory phase, not knowing where the endgame for large models was, so "looking at papers and seeking inspiration" was the norm.

Jane: Got it. So there wasn't that kind of "hard KPI pressure" for publication volume back then, right? Unlike SenseTime, which had very clear paper metrics in its early days. Although everyone is a research-oriented organization, Alibaba seems to have a more free atmosphere.

Gao Daiheng Sam: Yes, that's indeed the case. This freedom provided a lot of space for technical exploration.

Jane: When did you officially start to have the idea of entrepreneurship? Was it after you worked on that open-source community that you began to feel, "I need to go out and explore, even though the direction isn't fully set yet"?

Gao Daiheng Sam: That's right; it indeed started to take shape during that phase.

Jane: Why did you decide to leave Damo Academy at that time? Was it to explore the open-source direction, or were there other considerations? And who first proposed the initial form of the product that you and your partner later developed?

Gao Daiheng Sam: Initially, we did have some abstract discussions. I firmly believed that the new generation, especially a workplace community that attracts young people, absolutely cannot follow the old path of "posting resumes and flaunting degrees"; it needs to have a different approach. But to be honest, we discussed for a long time without coming to any clear conclusions.

At the beginning of this year, I was in the United States. The thought process was quite simple: I would first try to use Cursor (an AI code editor) to do some Vibe Coding and create a fun little application to test the waters. The core logic of this application was very precise: users input their name or Google Scholar link.

I know this group of young researchers very well—often the first thing they do when entering the lab is to open Google Scholar to see if their citation count has increased.

Jane: You've captured the pain point of researchers.

Gao Daiheng Sam: Exactly. The function I developed was: you paste the link, and the AI gives you a "spicy review." For example, it might tease you with comments like "not enough first-author papers, you need to work harder," or "why do you always fail to publish at top conferences," focusing on humor and fun. The development cost was extremely low, but after launching, we made two unexpected discoveries:

First, once the model had reasoning capabilities, it could provide very precise and abstract evaluations based on a person's achievements, even able to "roast" them quite accurately. I found that people actually enjoyed hearing the AI roast them; that "seeking to be scolded" mentality was quite interesting, while compliments seemed less engaging.

Second, after this little tool was up and running, I discovered that its potential for extension was exceptionally broad. It was based on the feedback from this "spicy review" tool that we began to deeply collide ideas and ultimately refined the current product form.

Jane: Understood, it grew out of a very small positive feedback. Very interesting.

The Talent Recruitment Dilemma at Sequoia Led Kelvin to See the Structural Gap in Recruitment in the AI Era

Aaron: Kelvin, please briefly introduce yourself.

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: My experience is quite straightforward; my career has been deeply rooted in HR and recruitment. A particularly special turning point was when I fortuitously joined Sequoia Capital, responsible for recruiting internal investors, including young talents in the technology and consumer sectors. After leaving Sequoia, I attempted a few entrepreneurial ventures. The first venture was actually quite similar to our current business logic: it was during the explosion of mini-programs, and I keenly sensed that the recruitment efficiency within the WeChat ecosystem (Moments, group chats) was surpassing traditional platforms like Liepin and Boss, so I created a recruitment mini-program.

Aaron: How did that attempt turn out?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Quite dramatically. The product launched, and within a week, the pandemic broke out. Although online growth was astonishing—hundreds of companies in the B-end spontaneously spread the word in groups, and within two weeks, 100,000 resumes poured in—the financing environment plummeted. At that time, people were still not accustomed to online meetings, and I couldn't even meet with investors. After struggling for a few months, that entrepreneurial venture ended without success, which became a significant regret for me. After that, I dabbled in cross-border e-commerce but ultimately returned to my "main track."

Aaron: Many people are curious, what are the standards for Sequoia to recruit young investors?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: The requirements change every year, but the core logic can be summed up in one sentence: "the absolute best among peers." This sounds abstract, but in sensory terms, it means that a 25-year-old should have a different aura at first glance. We don't limit backgrounds; journalists, product managers, and programmers are all welcome. As long as you possess strong deep thinking abilities and self-motivation, and can clearly distinguish yourself from your peers, that's the profile we are looking for.

Aaron: From an HR perspective, what are the core difficulties in recruiting for consumer or technology companies?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Helping portfolio companies recruit, the biggest challenge is actually "lack of fame." Regardless of whether Sequoia or Hillhouse is behind it, most candidates have no idea what these companies do. Low brand recognition is the biggest obstacle in recruitment.

In contrast, it's much easier to recruit for To C companies because they advertise every day. I have a deep impression, for example, introducing people to Pinduoduo went very smoothly because that catchy tune is everywhere. Before going public, Pinduoduo's ads were all over Shanghai, and their recognition was evident. But in the To B field, even for some cutting-edge directions that people have never heard of, achieving breakthroughs in talent recruitment is extremely difficult because no one outside knows about it.

Aaron: From generating demand to finally issuing an offer, how many steps does it typically go through, and how long does it take?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Generally speaking, it starts with a full-channel search: scanning online platforms, from domestic and international job sites to leveraging personal networks in Moments and group chats, even contacting people who "know the target talent" to find key traffic nodes; if you're feeling luxurious, you might hire a headhunter. In short, all channels will be tried.

It usually takes about one to two weeks to filter out unsuitable candidates and distill three to five complete profiles with good motivation. By this point, two weeks have passed. Then, interviews are arranged, and offers are discussed; if everything goes smoothly, it can take one to two months to finalize. Adding in the onboarding preparation period, it could be another three to four months. In other words, recruiting for a challenging position can take a whole quarter, even in the best-case scenario; many positions are even "unsolvable" and can never be filled.

Aaron: From your professional perspective, how would you describe DINQ's business in one sentence? What kind of product is it?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: If we set aside the AI technical shell, I believe it is the most efficient tool for all AI practitioners to express themselves. You see, our personal homepage is actually a highly efficient way of self-expression.

From the recruiter's perspective, our search engine is a more efficient talent search engine. It can basically directly replace the first two steps I just mentioned, helping recruiters save at least two weeks of blind search time.

Aaron: When did you realize that in this new AI track, the traditional methods of submitting resumes, LinkedIn profiles, and traditional recruitment processes had become ineffective and needed to be disrupted?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Although I haven't directly done recruitment in recent years, I've always carried the label of "someone who can help people recruit." Some emerging entrepreneurs in the AI field still come to me asking: "Kelvin, can you help me introduce some excellent algorithm engineers or full-stack developers?"

At that moment, I realized I was "out of touch." Previously, it was easy to introduce talent through first or second-degree connections, but after the rise of this wave of AI, I found that I didn't know anyone in the circle. This made me anxious: even though I wasn't directly in this field anymore, I didn't want to lose that professional label.

I realized that a whole new group of people had emerged. I know many CTOs in traditional fields, but they don't involve themselves in this area and don't understand this logic. We are no longer in an era where "just offering a 2 million annual salary can solve AI technical challenges by finding a traditional CTO." Talents like Sam and many top young people in the market are drifting outside traditional views, and we don't even know where they are; that was my dilemma at the time.

Aaron: What attempts did you make to solve this dilemma?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: I started researching where they actually appeared. I also consulted HR friends from large model companies: where do you go to find people? I found out that they actually had to go to GitHub and Google Scholar to "human flesh search," and it was quite difficult to find people on LinkedIn. Even if they found someone, they had to go through personal homepages to find contact information and send emails. The efficiency of industry recommendations was also low; while it could solve some problems, it was still all about finding people through "non-traditional channels." So I started to follow that approach to search.

Aaron: So it can be understood that it was precisely because you felt the original methods of finding people were too inefficient that you thought of creating the current product?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Yes. But to be honest, this product wasn't "made" by me; it was created by Sam, who made me realize, "Oh, this problem can be solved this way." I was a bit late to the game in this regard.

Aaron: How did you two initially meet?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: It's quite simple, actually. At that time, a friend asked me to find a cross-disciplinary talent who understood both trading and AI agents. I noticed a very famous project, which is the OS that Sam just mentioned. I saw a Chinese name—"Gao Daiheng"—among the authors in the paper, so I started using all my resources to find someone who might know him. Eventually, through an investor from an investment institution, I formally met Sam. This was actually my "old tactic"—leveraging the extensive network I built through recruitment.

Aaron: What was your first impression of Sam at that time? How did it change later? What prompted you to decide to work with him?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: To be honest, I didn't have a particularly deep first impression initially. During that time, I contacted many similar tech experts, and it was basically routine communication: I have an opportunity, would you consider it? He naturally declined my offer at that time.

At first, my understanding of him and the AI field wasn't very deep. The turning point came later when he had the idea of creating a recruitment product and realized that I was quite professional in this area, so he reached out to me for in-depth discussions. It was then that I gradually developed a clearer understanding and feeling about him. In the early days, we communicated online, and although we hadn't met in person, we got along very well.

I noticed that he exhibited a very broad learning attitude to get things done. When he heard that I understood recruitment, he relentlessly asked many very hardcore and detailed business questions. Later, I found out that he was self-taught in AI from a different field. I believe that once a person's self-learning ability is strong enough, it evolves into a fundamental habit, leading to breakthroughs in various aspects. So my core evaluation of him later became: he has a very strong self-learning ability.

Gao Daiheng Sam: Thank you for the affirmation, Kelvin. At that time, my thought was simple: after wrapping up that project, I wanted to explore new things. When we reviewed our respective strengths and underlying capabilities, I found that we had a deep understanding of the characteristics, cognition, and flow patterns of "people." I was thinking, can we do something centered around "people"?

Once this foundation was established, the most natural extension was the recruitment field, and at that time, the market demand gap was indeed huge. Based on this initial intention, I consulted Kelvin more. Initially, when we communicated, I was still in the United States, and Kelvin shared a lot of his deep insights into the human resources industry. As we talked more thoroughly, we both felt that we could work together to scale this endeavor.

Aaron: So you both reached a consensus on the general direction from the beginning, and the specific product form was continuously "collided" out by the two of you?

Gao Daiheng Sam: Yes. Regarding the product form, I hesitate to use the term "converged" because I believe that at the current stage of AI, no company can claim that its platform product has been fully defined. If the technology and model had truly "converged," companies wouldn't need to spend hundreds of millions in salaries to compete for those top Chinese researchers.

In the context of an industry that has yet to be defined, we achieved a phased consensus on the form: we believe that the current model aligns more with the intuition of young people. As for how it evolved? There are no shortcuts; it's simply because our contact with young people and the target user group is the closest and most frequent, so we understand best what they truly like.

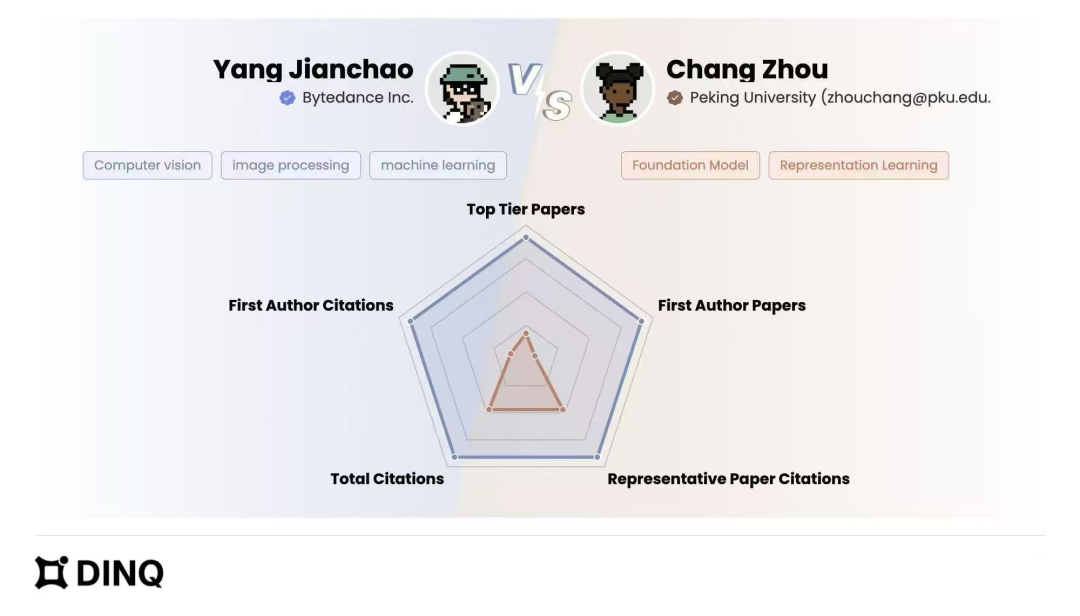

Yang Jianchao vs. Zhou Chang

Product Breakdown: How Does DINQ Use Agent Reasoning to End the Talent Search Dilemma in AI?

Aaron: The core of traditional recruitment is keyword matching. What dimensions does DINQ's talent assessment system have? What is the essential difference compared to traditional frameworks?

Gao Daiheng Sam: From a technical perspective, we are in an era of "deconstruction and reorganization (Remix & Decouple)," where the complexity of information is growing exponentially. This leads to a typical contradiction: a candidate's core label might be a model like "R2" or "拉网," but HR's search terms might be "image large model" or "video generation." In a lexical search mode like LinkedIn, if the terms don't match, that person might never be found.

Moreover, we surveyed over a thousand researchers at OpenAI and found that more than half of them don't even maintain a LinkedIn profile, or they don't have an account at all. The information of tech experts is often scattered across official blogs or secondary papers, making it extremely difficult to find people in the B-end.

Aaron: So what is your solution?

Gao Daiheng Sam: Since the channels are so fragmented—he might have a project on Hugging Face, posted a technical interpretation on Twitter, published a paper on arXiv, and shared a conference poster photo on Xiaohongshu—we decided to abandon the "LinkedIn Profile" centered approach and instead build a system primarily based on Agent invocation. We preprocess a large amount of data and embedding (vectorization) for top conferences and AI companies in advance, so when users query, the Agent can retrieve real-time information from the entire web for reasoning.

For example, the first author of Sora 2 is a Chinese named Li Liunian (Harold). If you ask traditional general large models or agent platforms, they basically won't be able to find him because the data isn't aligned. But our system can accurately capture him based on his papers, GitHub, and social media dynamics.

Aaron: I want to delve deeper into the issue of "fragmentation." Traditional recruitment heavily relies on LinkedIn, but the information of AI researchers and engineers is often scattered across platforms like Google Scholar and GitHub. Can you give a specific example to illustrate how severe this fragmentation is?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: The current pain point is that when HR receives a demand, the business side's requirements for young algorithm researchers have become extremely specific, such as needing to solve a highly niche problem like "character consistency in video generation." The biggest problem HR faces is that they have no idea where this group of people is.

Our tool allows HR to input all the fragmented information they have, first solving the breakthrough from "0 to 1." In the past, relying solely on snippets to search LinkedIn would likely yield no results because no one would put specific research achievements on LinkedIn. This is LinkedIn's biggest flaw—there's often only school background information, and the information density is too low.

If you're just looking to hire students from "Tsinghua or Peking University," LinkedIn can handle that; but if you're looking for someone who can solve a specific technical problem, the technical terminology in the industry isn't even standardized, so LinkedIn definitely won't find them, and platforms like Boss Zhipin or Liepin are even less likely—target candidates simply won't go to those places to seek jobs. This was almost "unsolvable" in the past.

The traditional clumsy method is to inquire and grind through papers, but it's unrealistic to expect HR to read papers, nor is it their job. Ultimately, they can only rely on word-of-mouth inquiries or internal referrals, which is extremely inefficient.

Aaron: If I were an HR at Meta looking to hire an AI Scientist, what would the typical process on DINQ look like?

Gao Daiheng Sam: We offer three modes:

First, if you have a clear demand, just send a brief message, like "I want to find someone for a specific direction at NeurIPS 2025, preferably with a work visa for the U.S."

Second, if you already have a JD (like on platforms such as Greenhouse), just throw the JD over, and the system will help you find people.

Third, if you already have a person, like A is very suitable but not available, or A is your employee, you can ask, "Find me someone similar to A," such as someone still pursuing a PhD or actively looking for opportunities. You can also ask, "Find someone born after 1995 who has made contributions in a certain direction and might be looking for opportunities," or even "go to SCI to find such people." All of that is possible.

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: I'll add to that. In the past, if finding someone followed a standard process, a professional HR or the most expensive headhunting company would first do extensive sourcing, creating a long list of 100 people. Then they would contact and eliminate candidates, mainly confirming two things: capability and willingness. Only if both matched would they proceed. After that, they would form a short list for the hiring manager (fund partner, CTO, etc.).

Now, we essentially produce a short list directly because the full-network sourcing has basically been done by the agent, so there's no need for people to spend time on that. The output is just the short list. Then people should focus on what they do best: direct communication and persuasion.

Aaron: I noticed you have a feature that allows candidates to "set their value (Package)," which has even attracted many professors from Stanford, Berkeley, and NYU to try it out. How is this generated? I tested it with Yao Shunyu, and he was valued at 10 million dollars.

Gao Daiheng Sam: We used publicly available data from Level.fyi to create a scoring model for talent levels and values. Originally, it was just for fun, and we didn't rigorously calibrate it, but the response exceeded our expectations. Yao Shunyu being assessed at 10 million dollars is actually quite accurate.

Aaron: How does this AI robot specifically analyze and categorize?

Gao Daiheng Sam: After users register, we vectorize their resumes and social media. When you search, the system performs intent recognition. For example, if you search for "top conference," we automatically map it to the latest CVPR or NeurIPS. If you're looking for someone born after 2000, the Agent will collect information from the entire web for reasoning. For a list of authors with hundreds of people, manual screening is impossible, but the Agent can instantly rank them based on importance.

Aaron: Do you encounter biases, such as some PhD students doing important work but not publishing it? Do you have mechanisms to correct such biases?

Gao Daiheng Sam: That's a great question. We will index arXiv content based on user queries later on, but we haven't achieved that in the current stage.

Aaron: How is the feedback from B-end users currently?

Gao Daiheng Sam: The team at Meta responsible for executive searches is already using it, and some overseas AI companies are also co-developing with us; they need extremely comprehensive reference frameworks.

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Domestic teams like Flow, 月之暗面, 智谱, and 爱诗科技 (PixVerse) are also quietly trying it out. The most common feedback word is "amazing." In the past, when HR received a vague demand, it caused significant internal friction; now, inputting a demand instantly makes the candidate profile concrete. HR would exclaim, "So this is exactly the type of person I'm looking for!" This leap from vague to clear is more valuable than simply finding someone.

Aaron: Are current clients more inclined to recruit senior scientists with experience from large companies, or do they place more emphasis on fresh PhD graduates?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Both demands exist, but currently, there are more leaning towards the latter. On one hand, senior scientists are very expensive; on the other hand, those well-known figures who are "on the surface" are generally known to HR. However, even when dealing with acquaintances, our tool still holds value: HR often provides feedback that they realize, after searching, "I added this person on WeChat, but I completely forgot about them." After all, it's hard for the human brain to remember those 5,000 people in WeChat.

Jane: Does this mean that in the AI era, the recruitment demand itself—especially for high-end talent—has undergone a dramatic change, leading to the existing perceptions of company HR no longer covering the current technological boundaries?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Exactly. You can see how ByteDance has adjusted: they have pulled many employees who were originally working on algorithms or products, but may not be "top-notch" technically, to work full-time in recruitment. Because these people understand the business and technology, they can more easily find the right candidates.

From the current feedback, the attempts by ByteDance's Seed and Flow teams have been very effective. Their high-end recruitment team has a large number of people who previously had no recruitment experience, all of whom have transitioned from business lines.

But currently, only large companies can afford to solve this in such a luxurious way. For most companies, being able to hire such people for their core business is already good enough; they wouldn't want to let them do recruitment. This "using a sledgehammer to crack a nut" model lacks universal significance.

Jane: I remember knowing some headhunters in the past; if a big company wanted to find scientists in North America, they could only look for headhunters who were deeply rooted in the area and knew many scientists. Even so, the talent profiles were still unclear, and they could only pull people in one by one for meetings. The entire process was extremely difficult to standardize; it was essentially "casting a wide net." The changes on the demand side here are indeed the most significant.

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Yes, that's the reality.

This conversation touches on the core technical barriers of the product and user experience details. Without omitting any content, I mainly optimized the coherence of the expression, transforming fragmented words from spoken language into a more professional narrative, and enhanced the technical depth in Sam's logic.

Aaron: Let me understand more deeply: does your product specifically read papers to identify content and match positions? How precise can your talent profile tags (Tags) be?

Gao Daiheng Sam: This demand will automatically trigger multiple dimensions of matching: first, public achievements, such as commercially impactful non-open-source results like Sora 2; second, popular projects or highly-rated results on Hugging Face; and further down, contributors who are "under the surface," such as papers published by universities like Sun Yat-sen University and Soochow University.

Currently, to balance efficiency, we mainly achieve precise matching by reading abstracts. If we were to perform full-text analysis, the token consumption would be enormous, and the processing cost per person would skyrocket, so we haven't launched the full-text reading feature yet.

Aaron: How many data sources have you integrated so far?

Gao Daiheng Sam: About twenty to thirty. We cover mainstream platforms like Google Scholar, Medium, and Twitter. Although arXiv hasn't been officially integrated yet, it's in the plan.

Aaron: Have you preprocessed the data from top conferences as well?

Gao Daiheng Sam: We preprocess the data from top conferences in advance. This is because the conference rankings are usually one-time events, allowing us to directly obtain the list of authors and conference names for that year.

Aaron: From a technical perspective, where are the most challenging aspects? Is it data scraping, cleaning and aligning, or privacy risk control?

Gao Daiheng Sam: There are many details, so it's hard to say "the most difficult," because any poorly executed step can become a shortcoming. I summarized three representative challenges:

Disambiguation: This is a classic problem in academic search. There are too many people with the same name now, so ensuring that no erroneous associations occur is crucial; once a wrong association leads to misidentifying someone, the user experience will be very poor.

Timeliness: For example, if you want to find an author who has switched from OpenAI to Meta, but the system still shows him at his old company, that's a timeliness issue. How do we dynamically update the database and synchronize information in real-time? The biggest pain point for traditional platforms is that they can't bear the costs of passive updates.

Agent Path Selection: Based on user needs, the system needs to determine where to search, how to shorten the path, and how deep to drill down. This involves a cross-game between depth-first and breadth-first strategies. In this process, we continuously upgrade the model's reading comprehension ability.

Aaron: Regarding the first point, can you explain with a more straightforward example? For instance, distinguishing between two people named Yao Shunyu, whose English names are also the same.

Gao Daiheng Sam: The criteria for differentiation mainly include several dimensions: the uniqueness of the Google Scholar ID, differences in photos, educational background, and different career trajectories. By combining these dimensions, we can accurately separate them.

Aaron: For the second point about updates, the traditional approach is to continuously follow the other party's dynamics. How do you capture real-time updates?

Gao Daiheng Sam: The core premise is that relevant information must exist on the internet. This group of technical talents rarely uses LinkedIn; they maintain personal homepages more. However, personal homepages are extremely fragmented, like independent sites on GitHub, where you can't find them without knowing the specific path. Our advantage lies in knowing where they are and having pre-cached the data to efficiently extract information from complex independent sites.

Aaron: In actual operation, have you encountered any tricky or unexpected cases?

Gao Daiheng Sam: Yes. A few days ago, I demonstrated to a friend and asked the system, "Among this friend's collaborators, who might be looking for opportunities?" The feedback was very precise, and this friend is a senior university professor. There's also a case with Su Jianlin (Su Shen): I wanted to see how many degrees of collaboration I had with him. Although we haven't directly collaborated, the system was able to trace the connections through intermediaries.

This illustrates an essence: when the model's intelligence level is high enough, reasoning ability is strong enough, and sub-page crawling capability is good enough, "less structure can lead to more intelligence." You can trust the model's judgment more.

Aaron: If a candidate hasn't updated their personal homepage but noted a new institution or company in a newly published paper, can you capture that?

Gao Daiheng Sam: Yes. What we do is aggregate information from the entire web. Even if the individual hasn't updated their homepage, we can capture their new movements through their latest academic trajectory.

Jane: Will media news reports serve as your information sources?

Gao Daiheng Sam: Information from centralized media often has delays. Currently, our more effective sources are social media, which have faster timeliness. Among large centralized media, only a very few will become our auxiliary references.

Aaron: Data inevitably involves privacy; how do you define which data can be used for evaluation and which cannot be touched?

Gao Daiheng Sam: We have strict definitions for private information. Phone numbers and WeChat IDs are considered "intrusive" contact methods, and we typically do not provide them. Emails are relatively non-intrusive. In fact, very few people leave personal phone numbers or WeChat on their personal homepages; the vast majority of what we use is publicly available information.

Aaron: If someone does not wish to be found on the platform, how do you handle that?

Gao Daiheng Sam: As long as there is a formal inquiry request, we will completely delete their information from the system to ensure it does not appear again.

Aaron: What is your favorite feature of DINQ?

Gao Daiheng Sam: My favorite is the Network feature. When you find a person, you can not only see them but also see the six collaborators they work with most closely. You can click into any node to see the social network centered around that person. This means you can pull out a whole set of talent clues through one point—including paper collaborations, GitHub contributions, and group relationships within the same company. It transforms the search for people from "point search" into "network expansion," making operations on the platform very smooth; you can see the whole picture with just a click.

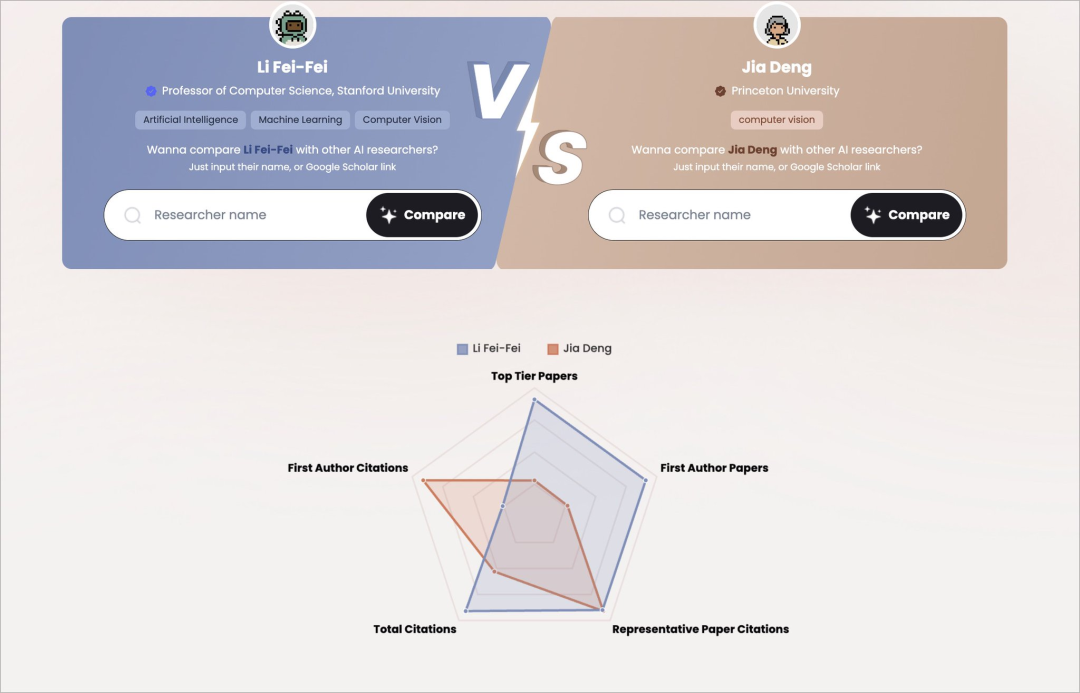

Aaron: I found the Compare/PK feature quite interesting during my trial.

Gao Daiheng Sam: That's right. The PK feature was initially designed to be quite abstract, like the red and blue battles in "The King of Fighters." Later, some friends provided feedback that people in academia and the open-source community might not think that "low star counts or low citations" represent weakness; they would joke, "You're just relying on age and not playing fair." So we have now made the PK interface more balanced. The original intention of this feature is to add a bit of fun to the serious process of searching for talent, without any overly utilitarian purpose.

Li Feifei vs. Jia Deng

Behind the Market and Business, the Efficiency War and Value War of AI Recruitment

Aaron: From a market perspective, what is the relationship between your product and traditional headhunting? Are they mutually exclusive or complementary?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: In the short term, it is definitely a complementary relationship. We help recruiters significantly save time in the "sourcing" phase, but the subsequent in-depth communication and persuasion still need to be done by people. The logic of corporate choice is very simple: if there is a budget, they outsource to headhunters; if there is no budget, they use tools to do it themselves; when encountering sensitive positions, they tend to take matters into their own hands. Currently, we play the role of an efficient tool.

In the long run, DINQ will squeeze out those lower-level headhunters. By "lower level," I mean those who can't even write prompts when facing AI products. In my recent research, I found that there are indeed headhunters who can't even come up with the first sentence of a demand; such people will be very endangered in the future.

Aaron: Can you elaborate on the specific cost structure? How do headhunters charge, and how does your business model intertwine with theirs?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: From a global perspective, top headhunters typically charge 20%–30% of the candidate's annual salary. If recruiting a senior executive with a salary of 1 million dollars, the agency fee can reach 200,000–300,000 dollars. In China, it's slightly lower but generally falls within 20%–25%.

Our pricing strategy has not been finalized yet, but the preliminary idea is to charge a couple of hundred to three hundred dollars per month. Even if you are "working to death" searching for people on the platform every day, the total cost for a year is still far cheaper than hiring a headhunter once. This calculation is something business owners can easily figure out.

Aaron: Are you currently positioning yourselves as a "super AI recruitment assistant," or as a future "AI headhunter"?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Actually, neither. I believe DINQ is an AI-native workplace social platform for people. Recruitment is just one form of professional social interaction; there are also vast demands for finding collaborators, clients, and technical exchanges. For example, a small company selling APIs needs to find developer clients, and designers working on AI animations need to exchange ideas. Our vision is by no means limited to recruitment.

Our positioning is similar to the early LinkedIn: to showcase oneself more efficiently and connect with others more effectively. Whether the actions taken after connecting are recruitment or chatting, the platform can accommodate both.

Gao Daiheng Sam: To add, our idea is to create a platform for all AI talents. The definition of AI-native talent is: using AI technology to enhance their productivity by an order of magnitude. Currently, those who are enhancing their productivity the most are algorithm developers, as their productivity tools are mature; design tools are also starting to reach households. In the future, more industries will be transformed, leading to the creation of specialized tools and work modes.

This era is decentralized, benefiting super individuals, but individuals need channels to connect with better opportunities and people. We provide better connections and outreach. In the future, opportunities will often not be about "people seeing and forwarding to friends," but rather agents automatically analyzing various opportunity platforms, and this will definitely happen. It requires a foundational carrier.

Thus, we allow the C-end to upload various social media to reflect comprehensiveness: in the past, resumes were for people to see; in the AI era, they are evaluated by both AI and humans together, with subjectivity, richness, and indefinability all reflected through photos, videos, and social media. As the model's understanding of multimodal data improves, the portrayal of individuals will become more three-dimensional.

From 2010, when Weibo and Twitter labeled people as human-readable labels, to today, where continuous embeddings outline individuals. In the future, the possibilities for personal development and the boundaries of abilities can also be predicted and planned to some extent. This is the platform's greatest value. From day one, we attract users with core technology; currently, the core is the matching engine, which draws people in.

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Recently, we conducted a small-scale testing campaign, and the results completely exceeded expectations.

First, the diversity of professions is extremely high. Not only do we have the chief scientist from IKEA and the chief AI engineer from Capital One, but there are also many unexpected individuals. For example, an Egyptian girl who delivers clients through AI animations on Twitter; there’s even an Egyptian user labeled as a "football coach," who turns out to be a coach using AI for data training analysis.

Secondly, the geographical distribution is very broad. Although it was just a fine-tuning of the campaign, users can be found in every corner of the world, except for the poles. From Egypt in Africa to the Middle East, India, and then to Denmark and Italy, the whole world is getting excited about AI. This far exceeds our initial expectation of being limited to the "Bay Area + Haidian."

Aaron: What will the future business model be—based on Credits, subscription, or pay-for-results?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: The preliminary plan is to charge based on search Credits, keeping it simple. The C-end will be free for now; we want to observe user behavior and essential needs after the user base grows before making a decision. The B-end will adopt a model similar to agent tool companies, selling based on Credits.

Jane: Have you considered making the C-end a community-type product?

Gao Daiheng Sam: The product itself can carry community functions. You can think of it as an "AI version of Linktree" with chat features. Although we haven't opened up user posts for daily updates yet, because the stickiness of such content is insufficient in the early stages of a new platform.

Jane: If you were to present the TAM of the AI recruitment market to investors, how would you describe it?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: We used to think that AI-related practitioners only numbered in the millions, but now we find that AI Users are actually a much larger base, exceeding 100 million globally. They also need to seek collaboration and opportunities worldwide. If the platform can make these extremely low-probability connections easier, the potential is limitless.

Gao Daiheng Sam: The core value of the platform lies in using AI to serve users well. We will quickly transition to a recommendation model: as we learn more about users, recommendations will become increasingly precise. In the future, users will not only find collaborators here but also mentors and partners.

Jane: This is a longer-term matter. Short-term TOB, but the long-term ceiling is higher and more adaptable to the present.

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Exactly. Moreover, our real business isn't strictly TOB/TOC, because every B is also a C at work; essentially, it's a real person using it, just in a work context more often.

Gao Daiheng Sam: Let me elevate this point: the core value of the platform is that AI can help serve users well. Traditional platforms create value through the supply side and users together; but today, like ChatGPT, a dialogue box can also become a platform because the large model itself provides intelligent services. We are the same: as long as the platform's intelligence is high enough and can solve enough problems, you become an input box, and users will come to use it.

We will quickly transition to a recommendation model. Initially, I didn't understand user problems, and pushing people right away was random. As we learn more about users, with overlapping users inside and outside the platform, recommendations will improve and become more accurate.

In the future, users will not only look for collaborators but also mentors and partners. In the past, without AI capabilities, it was impossible to make the most rational trade-offs: to evaluate all potential mentors and assess them, but the efficiency of information possession and processing was too low. Today, with an engine, this is possible. Our upcoming version will have a feature called "find my adviser"; finding partners follows the same logic.

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: This is no joke. Many people meet and marry in work contexts, which is a very real demand. Some even look for partners on LinkedIn. As long as we grow large enough, it will inevitably happen over time.

Jane: This is indeed very attractive to investment institutions. For example, firms like Sequoia that encourage internal entrepreneurship would have a huge demand if they could directly connect with core talents through the platform.

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Exactly.

Jane: Is it difficult for traditional LinkedIn teams to replicate your data sources and architecture?

Gao Daiheng Sam: From an architectural perspective, our asynchronous search architecture is highly competitive. If open-sourced, it wouldn't be hard to get 10,000 stars.

Replicating a version might only take a talented person five hours, but the real barrier lies in error judgment, path selection, and long-term parameter tuning. Because there are no standard answers in the AI field, if you don't understand the business logic, the tuning process will be extremely lengthy.

Aaron: Recently, large companies have been aggressively poaching talent, with Tencent offering double salaries and Alibaba also ramping up efforts. What do you think about the AI recruitment market in the next two to three years?

Gao Daiheng Sam: A clear trend is that, aside from top-tier talent, there is actually a greater gap in mid-level talent. According to the chief economist at Indeed, the current gap in the U.S. is 2 million, focusing on talent at the AI application layer, with an average annual salary of $206,000.

The outside world always focuses on who Zuckerberg or Zhang Yiming is poaching; those are indeed expensive but very few. A much larger group consists of open-source contributors, authors of small papers, and outstanding young people in small companies, whose turnover rates are higher. Our core strategy and advantage lie in the fact that we have already mastered the top tier of talent, allowing us to achieve a "top-down" dimensionality reduction attack.

Jane: Have you estimated how many top talents are being fiercely competed for by large companies globally?

Gao Daiheng Sam: Globally, it's about 100,000 to 300,000. Moreover, the talent landscape is rapidly expanding: five years ago, it was mainly CV (computer vision) and NLP (natural language processing), but now it has added many fields such as embodied intelligence, AI agents, RAG, vector databases, etc., with positions growing non-linearly.

Jane: Five to ten years from now, what role do you hope DINQ will play?

Gao Daiheng Sam: I hope that in five years, every AI practitioner will have a DINQ Card that integrates all their technical channels and social tags. On the platform, they will not only find opportunities but also meet friends outside their circle and even find like-minded partners. I hope the user base in five years can reach 10 million.

Team, Culture, and the Organizational Design of "AI-native Companies"

Jane: What is the current size of your team?

Gao Daiheng Sam: Currently, there are 8 full-time employees.

Jane: Are you using your own product to recruit?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: We just started using it. I joked with the technical lead that my biggest wish is to be able to recruit all the talent using DINQ next year. Because the initial talent we found was too high-level for us to offer (laughs).

But I was pleasantly surprised that we have already started uncovering some "underwater" treasures. A growth lead I recently spoke with was discovered and contacted through DINQ; we just added WeChat to prepare for deeper communication. Finding like-minded people on the platform has completely exceeded my expectations.

Gao Daiheng Sam: The search experience is very intuitive. For example, if you want to find someone with GTM (go-to-market) experience at a certain company, you can get results in just a sentence or two.

Jane: Just one or two sentences?

Gao Daiheng Sam: Yes. Users don't need to go through complex psychological preparations like writing traditional JDs. In DINQ, you can ask whatever comes to mind without any psychological burden.

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Writing JDs used to be very difficult because the requirements were too high and the demands were vague. With our tool, you can first input a general direction and run it. If the results aren't right, you can continuously refine through multiple rounds of dialogue: for example, "needs to be younger" or "needs to be more underwater." Through this multi-round narrowing down, you can finally lock in a few targets to contact directly.

Jane: What are the keywords of your team culture? How does this culture reflect in the product logic?

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: I think the word "pure" is more fitting.

Gao Daiheng Sam: Exactly, pure. We don't have a lot of messy affairs here; everyone works like they are in a studio painting, without rigid fixed hours. This purity is also reflected in product choices. For example, the logic for assessing value is entirely decided by me; our search function generously displays Network and Profile, rather than masking candidates like some products do to force users to pay. That kind of treating people as assets and trying to "inflate" them is too petty.

We pursue a "fully differentiable" approach in the AI era. When the user base reaches hundreds of thousands in the future, you can directly contact people you find within the platform.

Jane: Your product design is very simple yet sophisticated.

Gao Daiheng Sam: This is related to my background in architecture; we have a taste for aesthetics. Since we have previously worked on AI projects, we know what kind of visual experience users prefer.

Jane: One last question: for young AI students or engineers today, what advice do you have for them to be more effectively discovered by large companies or peers?

Gao Daiheng Sam: Just one sentence: Building in Public. Write more blogs, articles, and code, and share your views. What impresses me most is Su Jianlin (Su Shen); he started writing blogs in high school and has persisted for over a decade, becoming the "Su Shen" everyone knows today. His technology has become a standard practice for large models. You have to persist long enough to see good results. Don't be obsessed with doing those so-called "confidential big things" at the company; truly good things must be brought out to withstand criticism and evaluation.

Sun Chenxin Kelvin: Changes in China are also happening quickly. There are many researchers sharing their daily lives, works, and conferences on Xiaohongshu, bringing "research life" to life. People are discovering that these researchers are also real individuals, with pets and personalities. Those who were once under the surface are now stepping into the light through social media.

Jane: Indeed, on Xiaohongshu, you can see technical experts like Professor Shen Qinghong, who rarely appeared on social media before. That concludes our interview today; thank you both for your time.**

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。