This will be the content we will delve into next: how developers can use x402 without worrying about future failures.

Written by: Sumanth Neppalli, Nishil Jain

Compiled by: AididiaoJP, Foresight News

Programmatic Payments vs Advertising

There are two distinctly different schools of thought in the crypto space. One perspective believes that everything is a market, and pricing things can provide clarity. The other believes that crypto is a better financial technology infrastructure. Because, like all markets, there is no single truth. We are just sorting through all possible patterns.

In today’s topic, Sumanth will analyze how a new payment standard is evolving on the web. In short, it poses a question: what would happen if you could pay for every article? To find the answer, we go back to the early 1990s to see what happened when AOL tried to price internet access by the minute. We explore Microsoft's path to pricing its SaaS subscriptions.

In the process, we clarify what x402 is, who the key players are, and what it means for platforms like Substack.

The business model of the internet is disconnected from how we use it. In 2009, the average American visited over a hundred websites per month. Today, the average user opens fewer than thirty apps per month, but spends much more time within them. Back then, it was about half an hour a day; now it’s close to five hours.

Winners like Amazon, Spotify, Netflix, Google, and Meta have become aggregators, gathering consumer demand and turning roaming behavior into habits. They price these habits in the form of subscriptions.

This works because human attention follows patterns. Most of us watch Netflix most nights; we order from Amazon weekly; the Prime membership bundle includes delivery, returns, and streaming services for $139 a year. Subscriptions eliminate much of the ongoing pain. Amazon now pushes ads to subscription users to increase margins, forcing users to either watch ads or pay more. When aggregators cannot justify subscriptions, they revert to an advertising model like Google, which monetizes attention rather than intent.

Let’s look at what’s in advertising now:

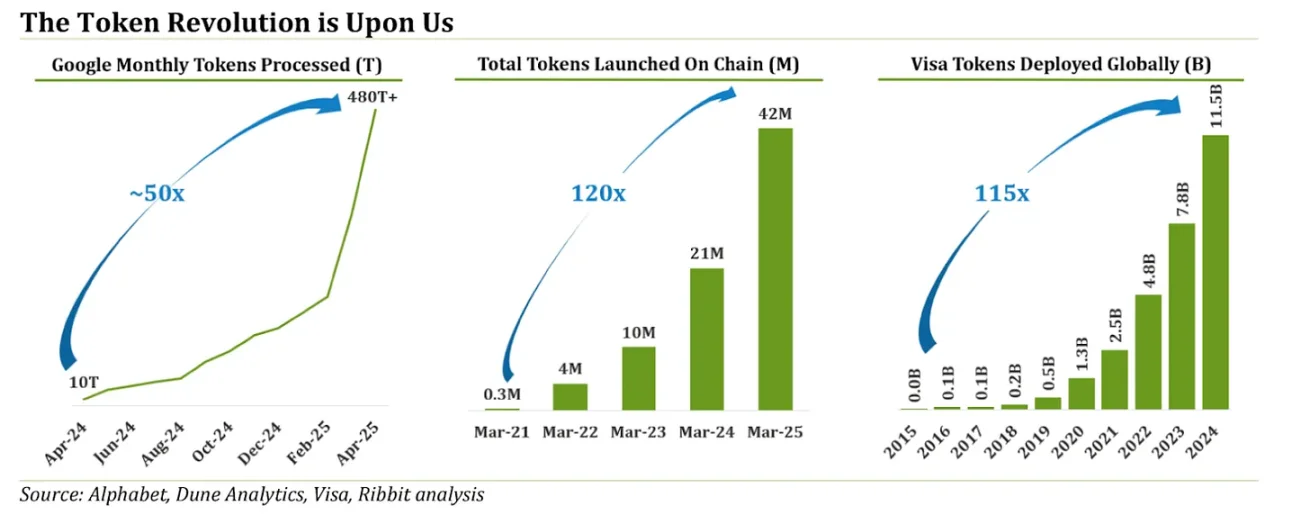

Bots and automation now account for nearly half of web traffic. This is primarily driven by the rapid adoption of AI and large language models, making it easier to acquire and scale bots.

API requests account for 60% of the dynamic HTTP traffic processed by Cloudflare. In other words, machine-to-machine communication has taken over a large portion of the traffic.

We designed today’s pricing models for a purely human internet, but the current traffic is machine-to-machine and bursty. Spotify on the commute, Slack during work hours, Netflix at night. Advertising assumes eyeballs, that someone is scrolling, clicking, thinking. But machines have neither habits nor eyeballs. They have triggers and tasks.

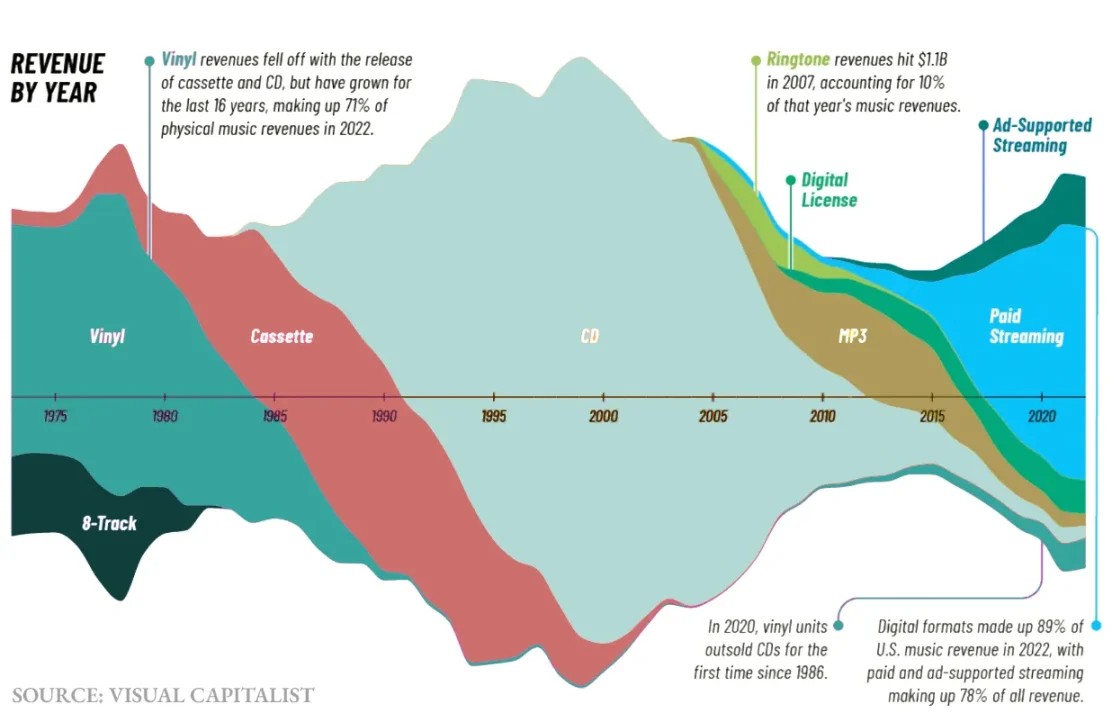

Content pricing is not only a function of market constraints but also a function of the underlying distribution infrastructure. Music existed in albums for decades because physical media required bundling. The cost of burning one song or twelve songs on the same CD is nearly the same. Retailers need high margins, and shelf space is limited. In 2003, when the distribution medium shifted to the internet, iTunes changed the accounting unit to songs. You could buy any song from iTunes for $0.99 and sync it with your iPod.

Unbundling increased discoverability but also eroded revenue. Most music fans buy hit songs rather than those ten filler tracks, compressing many artists' per capita income.

Then, when the iPhone emerged, the infrastructure changed again. Cheap cloud storage, 4G, and global CDNs made accessing any song instant and seamless. Phones are always online, providing instant access to an infinite number of songs. Streaming re-bundled everything at the access layer: $9.99 a month for all recorded music.

Music subscriptions now account for over 85% of music revenue. Taylor Swift is unhappy about this: she was forced back to Spotify.

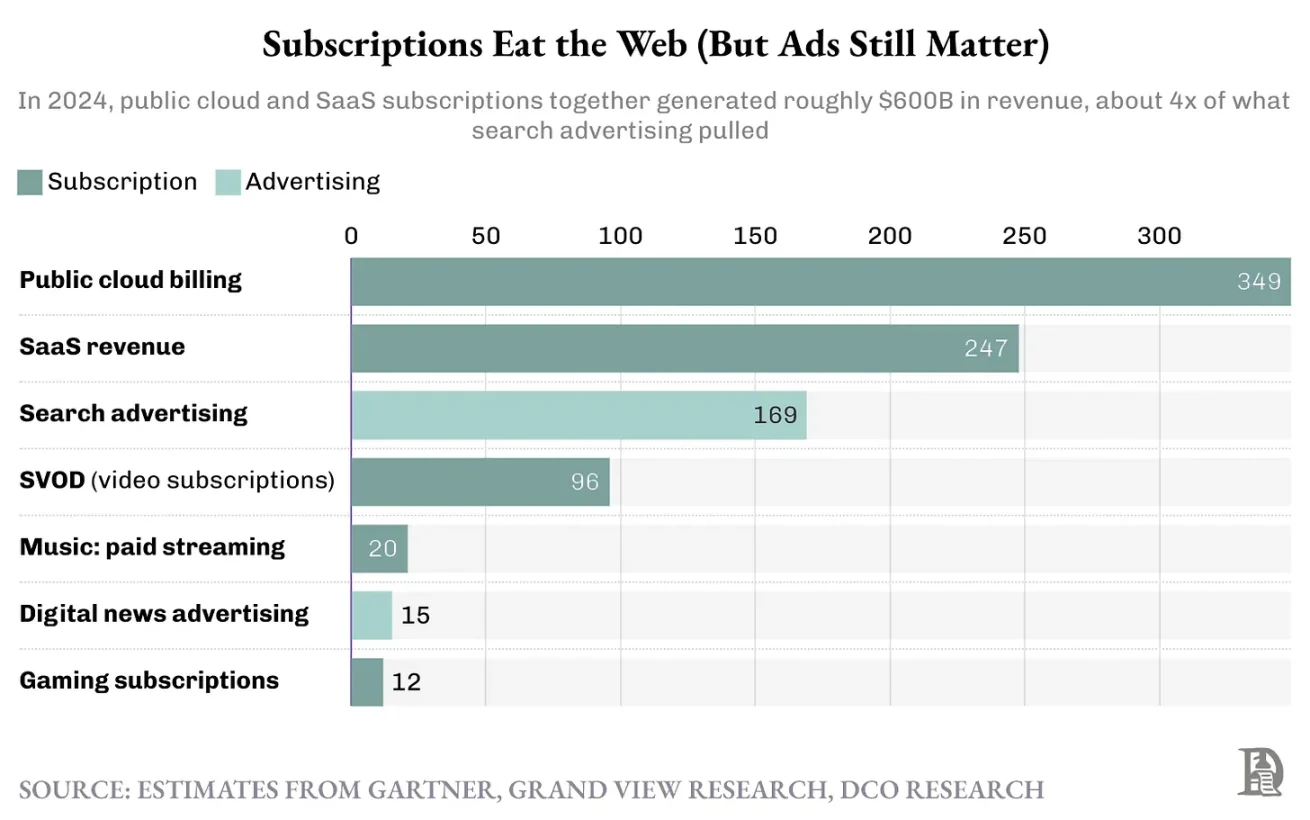

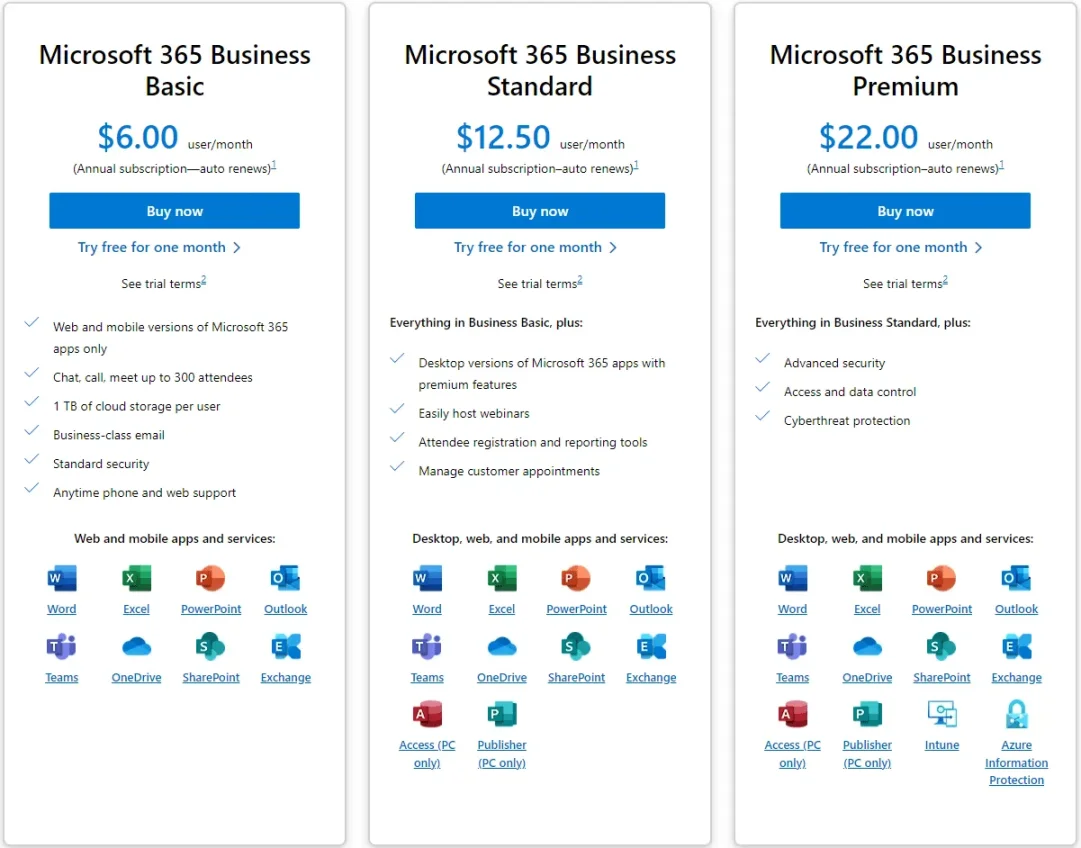

Enterprise software follows the same logic. Because products are digital, vendors can charge for the exact resources used. B2B SaaS vendors offer predictable access to services monthly or annually, often charging "per seat" and providing tiered features with limitations, such as $50/user/month, plus $0.001 per API call.

Subscriptions cover predictable human usage, while metering handles burst usage by machines.

When AWS Lambda runs your function, you pay precisely for what you consume. B2B transactions often involve bulk orders or high-value purchases, leading to larger deal sizes and significant recurring revenue from smaller, more concentrated customer bases. Last year, B2B SaaS revenue reached $500 billion, twenty times that of the music streaming industry.

If most consumption is now machine-driven and bursty, why are we still pricing like it’s 2013? Because we designed today’s infrastructure for human choices made occasionally. Subscriptions became the default because one month’s decision outweighs a thousand small payments.

It’s not cryptocurrency that created the underlying infrastructure capable of supporting micro-payments. There are factors in that direction, but the internet itself has become such a massive beast that it needs new ways to price usage.

Why Micro-Payments Failed

The dream of paying by the cent for content is as old as the web itself. The Millicent protocol from digital device companies promised transactions under a penny in the 1990s. Chaum’s DigiCash conducted bank pilots, and Rivest’s PayWord solved cryptographic issues. Every few years, someone rediscovers this elegant idea: what if you could pay $0.002 for every article, $0.01 for every song, just their cost?

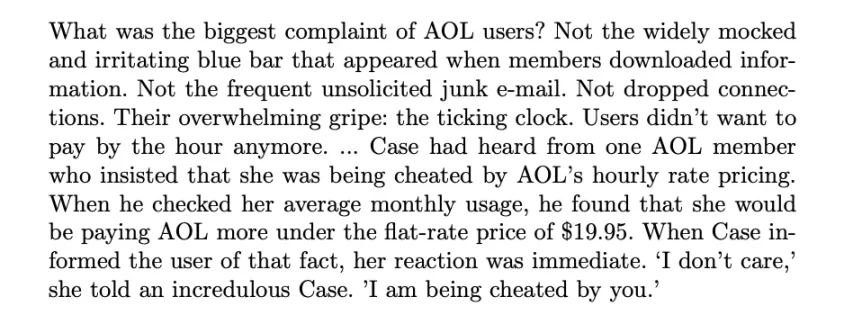

AOL learned this lesson at a considerable cost in 1995.

Source - The Case Against Micro-Payments

They charged by the hour for dial-up internet access. For most users, this was objectively cheaper than a flat-rate subscription. However, customers hated it because it created a mental burden. Every minute online felt like a meter running, with every click carrying a tiny cost. People couldn’t help but record each micro-cost as a "loss," even if the amount was small. Every click became a micro-decision: is this link worth $0.03?

When AOL switched to unlimited plans in 1996, usage doubled overnight.

People pay more to reduce thinking. "Pay precisely for the content you use" sounds efficient, but for humans, it often feels like anxiety with a price tag.

Audrey K. D. summarized this in his 2003 paper "The Case Against Micro-Payments": people pay more for flat-rate plans not because they are rational, but because they crave predictability over efficiency. We would rather pay $30 more per month for Netflix than optimize every $0.99 rental. Later experiments, like Blendle and Google One Pass, tried to charge $0.25 to $0.99 per article but ultimately failed. Unless a significant proportion of the readership converts, unit economics don’t work, and the user experience adds cognitive burden.

Subscription Hell

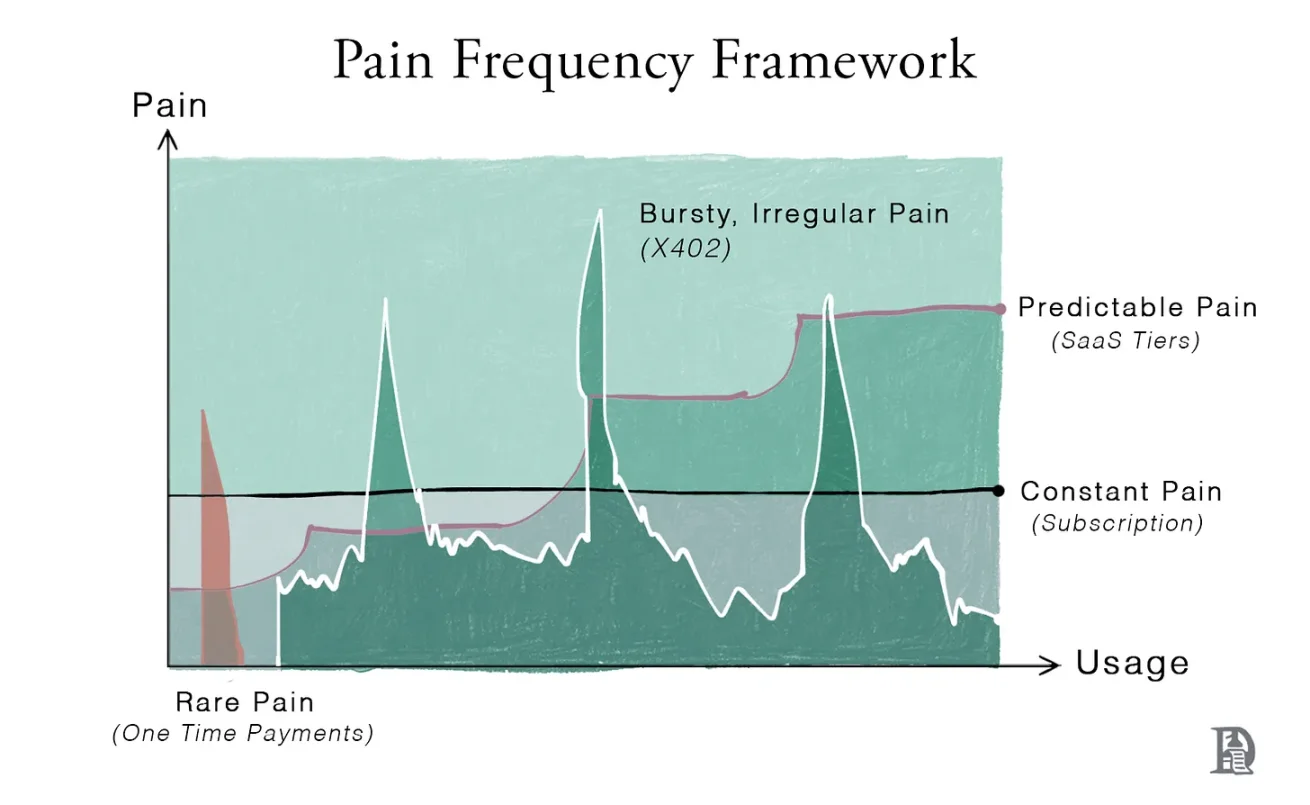

If we crave the simplicity of subscriptions, why are we complaining about subscription hell today? A simple way to understand pricing is to ask yourself how frequently you feel the pain that the product eliminates.

Entertainment demand is infinite. The black line in the chart represents this constant pain point, a shared dream between users and companies for a flat, predictable, constant pain curve. This is why Netflix transformed from a quirky DVD mailing service to a member of the elite FAANG club. It offers endless content and eliminates billing fatigue.

The simplicity of subscriptions has reshaped the entire entertainment industry. As Hollywood studios watched Netflix’s stock soar, they began to reclaim their content libraries to build their own subscription empires: Disney+, HBO Max, Paramount+, Peacock, Apple TV+, Lionsgate, and more.

Fragmented content libraries force users to purchase more subscriptions. If you want to watch anime, you need a Crunchyroll subscription. If you want to watch Pixar movies, you need a Disney subscription. Watching content has become a portfolio-building problem for users.

Pricing depends on two things: how precisely the underlying infrastructure can measure and settle usage, and who must make the decision on the value of each consumption.

One-time payments work very well for rare, bursty events. Buy a book; rent a movie; pay a one-time consulting fee. The pain hits hard once and then disappears. This model works when tasks are infrequent and the value is clear. In some cases, this pain is even desirable, and we romanticize the trip to the theater or bookstore.

When usage is measured precisely, pricing can align with the unit of that work. That’s why you wouldn’t pay for half a movie. The value there is ambiguous. Figma cannot extract a fixed portion from your monthly output; creating value is hard to measure.

Even if it’s not the most profitable, charging a monthly fee is much easier.

Metering is different: the cloud can observe every millisecond. Once AWS can measure execution at such a fine granularity, renting an entire server no longer makes sense. Servers only start when needed, and you only pay while they run. Twilio does the same for telecommunications: one API call, one text segment, one charge.

Ironically, even where we can measure perfectly, we still charge like cable TV. Using meters to run in milliseconds, but funds flow through monthly credit card subscriptions, invoice PDFs, or prepaid "credit" buckets. To achieve this, every vendor puts you through the same hurdles: creating accounts, setting up OAuth/SSO for authentication, issuing API keys for authorization, storing cards, setting monthly limits, and praying not to be overcharged.

Some tools allow you to pre-load credits. Other tools, like Claude, limit you to lower-tier models when you reach your quota.

Most SaaS lives in the green "predictable pain" zone. It's too frequent for one-time purchases and too stable to justify precise event-based metering, so the conventional approach is tiered pricing. You choose a plan that fits your typical monthly usage, and upgrade when your usage exceeds the limit.

Microsoft's 1TB limit per user is an example; it distinguishes light users from heavy users without needing to meter every file operation. The CFO restricts the number of users needing access to higher tiers by allocating permissions.

The Chaotic Middle Ground

A concise way to sort pricing models is to use a two-dimensional graph, with the x-axis representing usage frequency and the y-axis representing usage variance. Here, variance refers to burstiness, the degree of fluctuation in a single user's pattern over time. Watching Netflix for two hours most nights is low variance; an AI agent that hits 800 API calls in ten seconds and then stays quiet is high variance.

In the lower left corner is one-time purchases. When tasks are rare and predictable, simple pay-as-you-go pricing is effective because you feel the cost once and move on.

In the upper left corner is the chaotic, random web, with irregular news frenzies, link jumping, and low willingness to pay. Subscriptions seem excessive, while micro-payments per click collapse under decision-making and transaction friction. Advertising becomes the financing layer, aggregating millions of tiny, inconsistent views. Global advertising revenue has surpassed $1 trillion, with digital ads accounting for 70% of spending, indicating how many networks live in this low-commitment corner.

The lower right corner is where subscriptions make a lot of sense. Slack, Netflix, and Spotify align with human daily rhythms. Most SaaS lives here, separating heavy users from light users through tiers. Most products offer free tiers to encourage users to start using their products, then gradually shift their usage from the upper left to the lower right through daily, stable habits.

Subscriptions account for approximately $500 billion in global annual revenue.

The upper right corner is where the modern internet's focus lies, including LLM queries, agent operations, serverless bursts, API calls, cross-chain transactions, batch jobs, and IoT device communication. Usage is both continuous and volatile. Fixed-seat fees misprice this reality but lower the psychological barrier to starting to pay. Light users overpay, while heavy users are subsidized, and revenue drifts further from actual consumption.

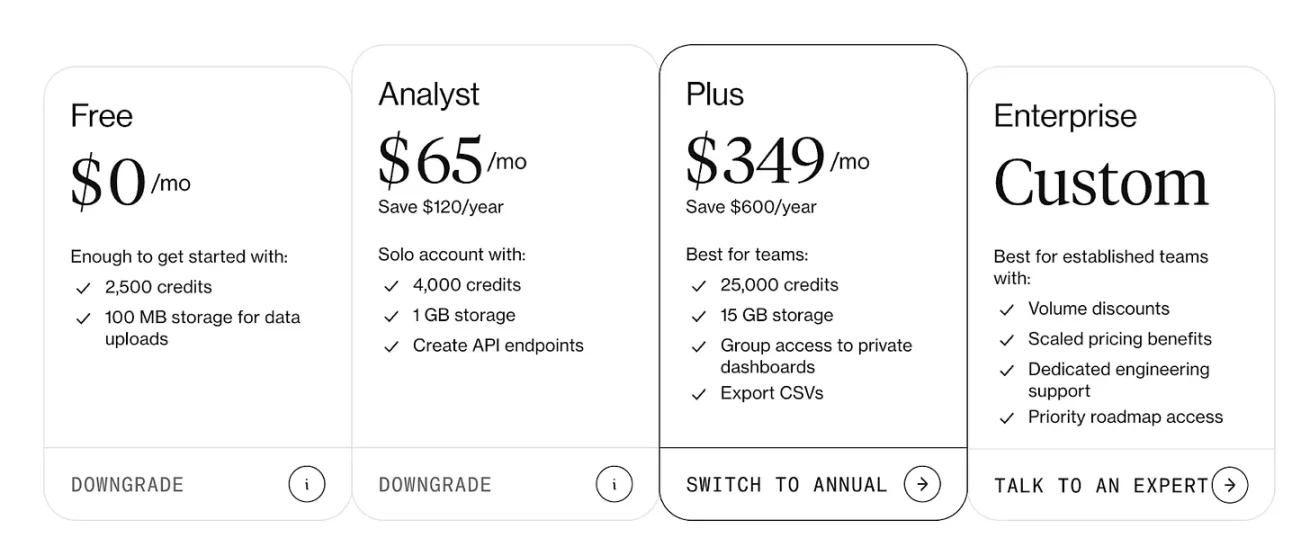

This is why seat-based products have been quietly shifting toward metering models. Retain basic plans for collaboration and support, but charge for heavy loads. For example, Dune offers limited credits monthly. Small, simple queries are cheap, while longer-running large queries consume more credits.

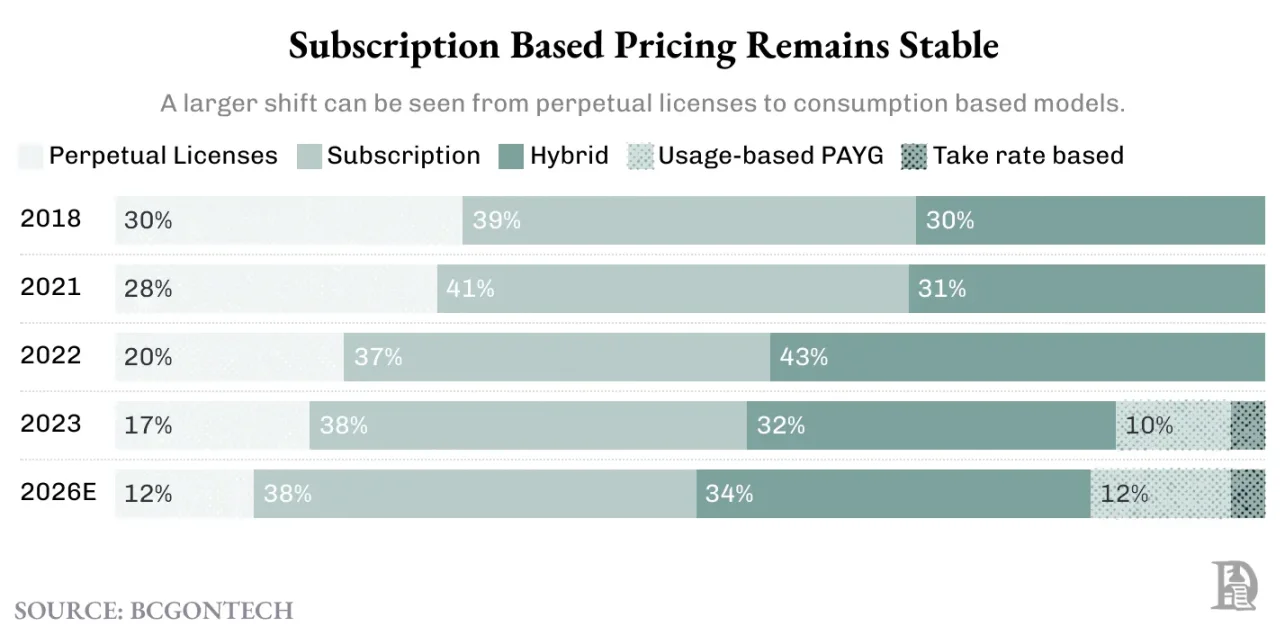

Cloud services have standardized billing by the millisecond for compute and data, while API platforms sell credits that scale with actual work. It is moving toward linking revenue with the smallest units observable by the network. In 2018, less than 30% of software adopted usage-based pricing. Today, usage-based pricing has nearly reached 50% by eroding commission-based pricing, while subscriptions still dominate at 40%.

If spending is shifting toward consumption, then the market tells us that pricing hopes to stay in sync with work. Machines are rapidly becoming the largest consumers of the internet, with half of consumers using AI for searches. Moreover, the content created by machines now exceeds that created by humans.

The problem is that our infrastructure still operates on annual accounts. Once you register with a software provider, you gain access to their dashboard, which contains API keys, prepaid credits, and end-of-month invoices. This is fine for habitual humans; but for bursty software, it becomes cumbersome. In theory, you could set up monthly recurring billing using ACH, UPI, or Venmo. However, these require batch processing to be usable, as their fee structures collapse under high-frequency traffic below a penny.

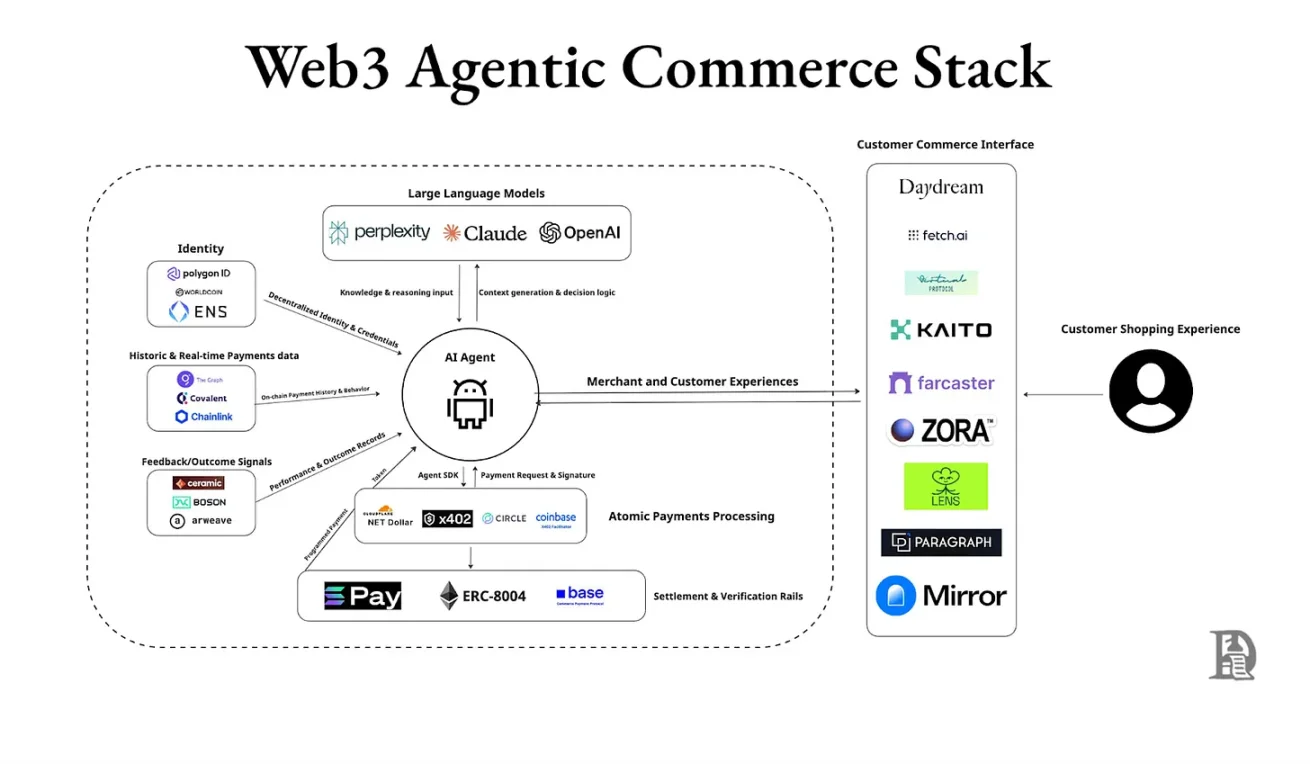

This is where cryptocurrency is crucial to the economics of the internet. Stablecoins provide programmable, global, fine-grained payments down to fractions of a cent. They settle in seconds, operate around the clock, and can be held directly by agents rather than being trapped behind bank user interfaces. If usage is becoming event-driven, settlements should be too, and cryptocurrency is the first infrastructure that can keep up.

What is x402

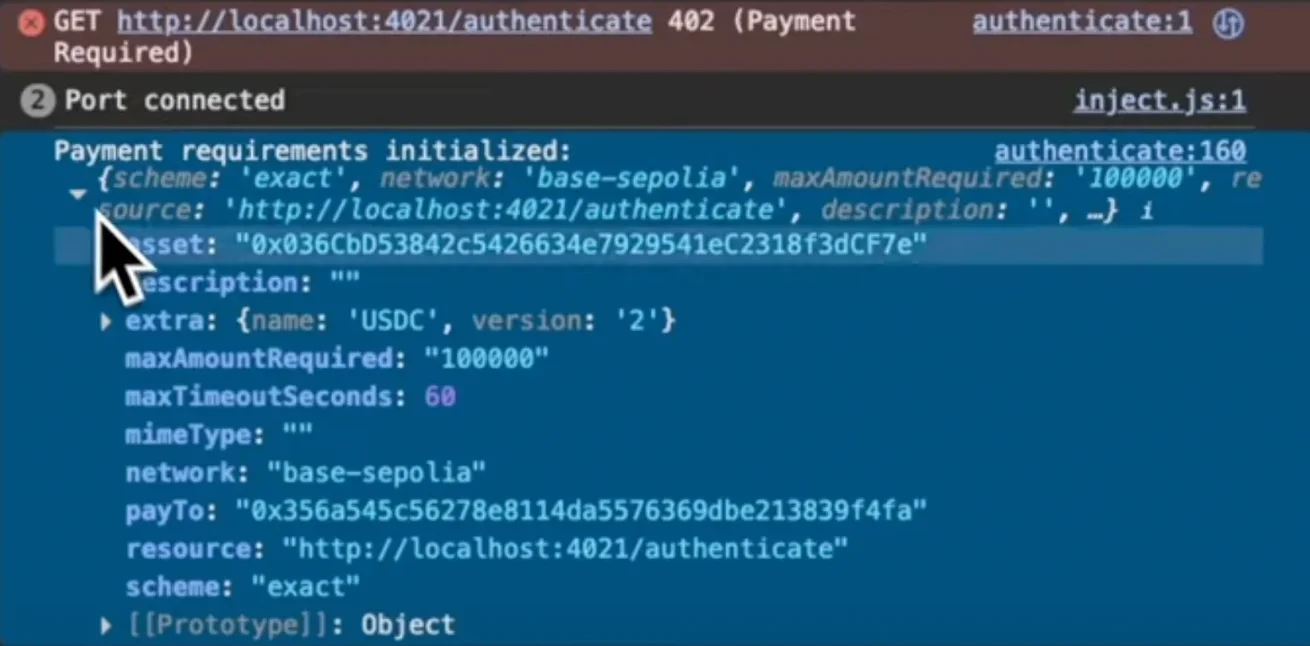

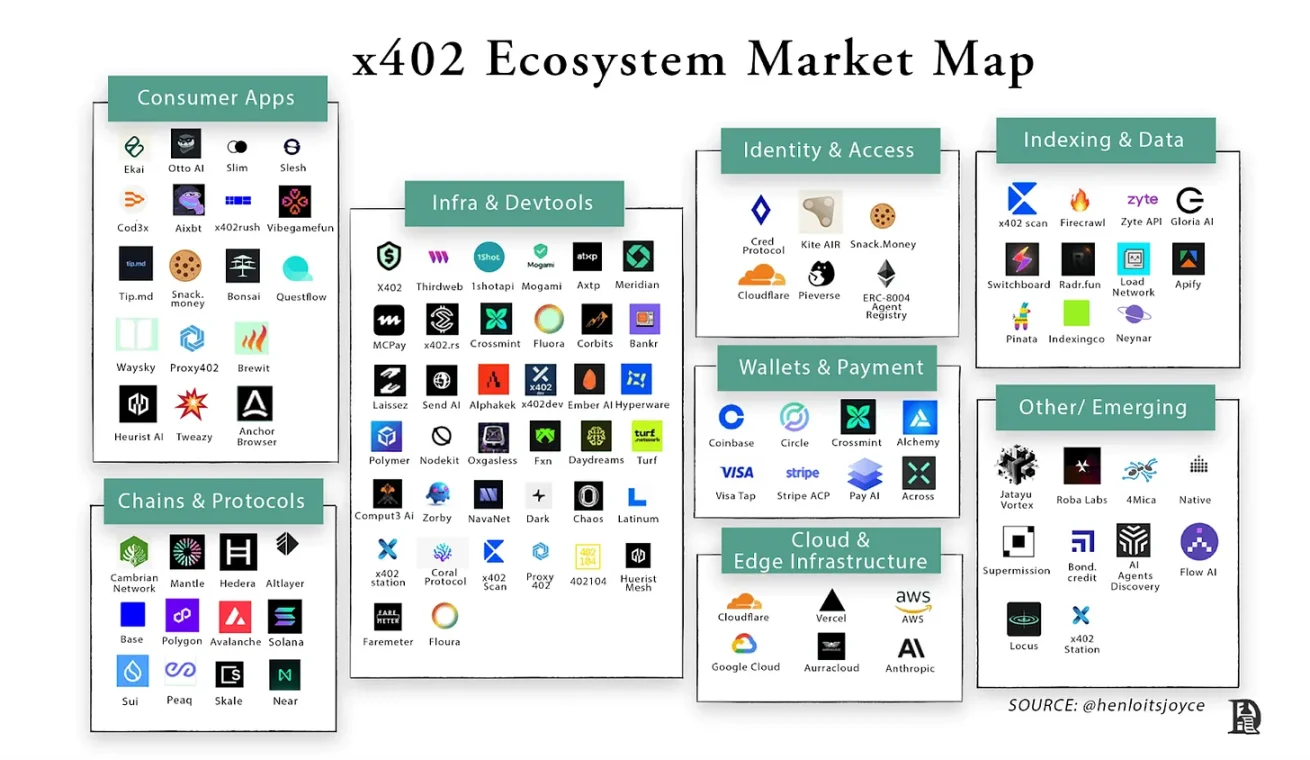

x402 is a payment standard that works in conjunction with HTTP, utilizing the long-standing 402 status code reserved for micro-payments.

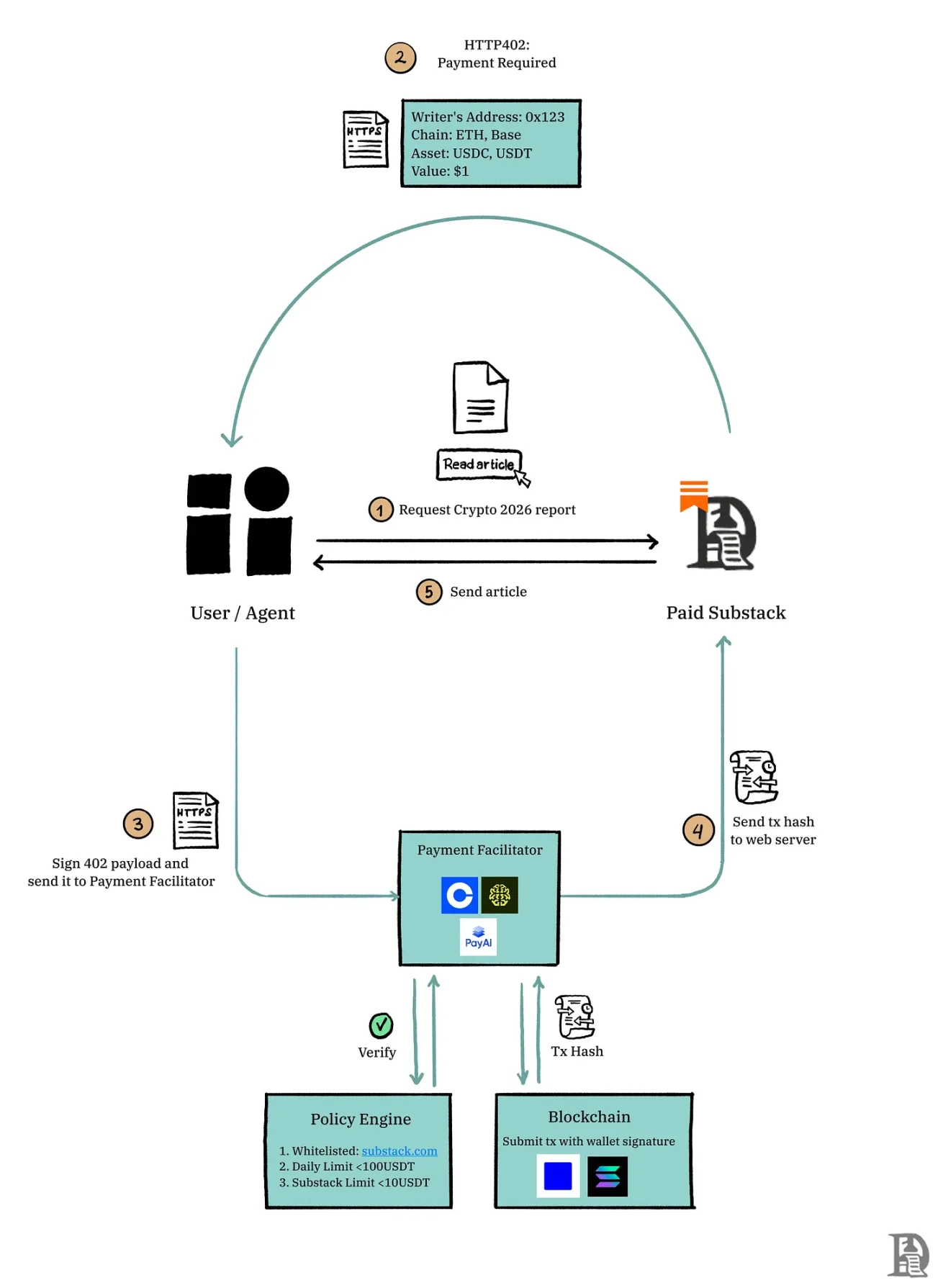

x402 is simply a way for sellers to verify that a transaction has been completed. Sellers hoping to accept on-chain payments without gas fees via x402 must connect to facilitators like Coinbase and Thirdweb.

Imagine Substack charging $0.50 for a premium article. When you click the "Pay to Read" button, Substack returns a 402 code containing the price, accepted assets (like USDC), network (like Base or Solana), and strategy. It looks like this:

Your Metamask wallet authorizes $0.50 by signing a message and passes it to the facilitator. The facilitator sends the text on-chain and notifies Substack to unlock the article.

Stablecoins make accounting easy. They settle at network speed, with tiny denominations, and do not require opening accounts with every vendor. With x402, you don’t need to pre-load five credit buckets, rotate API keys between different environments, or discover at 4 AM that your quota has run out, causing your job to fail. Human billing can remain where credit cards are most effective, while all bursty, machine-to-machine paths become automated and cheap in the background.

You can feel the difference in agent-based checkout. Suppose you try a new fashion style on Daydream (an AI fashion chatbot). Today, the shopping process redirects you to Amazon so you can pay using saved card information. In the world of x402, the agent understands the context, retrieves the merchant's address, and pays from your Metamask wallet without leaving the conversation thread.

The interesting part about x402 is that it is not a single entity; it consists of various layers you would expect to find in real infrastructure. Anyone building AI agents through Cloudflare's Agent Kit can create bots priced by operation. Payment giants like Visa and PayPal are also adding x402 as supported infrastructure.

QuickNode has a practical guide for adding x402 paywalls to any endpoint. The direction is clear: unify "agent-based checkout" at the SDK layer and make x402 the way agents pay for APIs, tools, and ultimately retail purchases.

Integrating x402

Once the network supports native payments, an obvious question is where it will first emerge. The answer lies in high-frequency usage areas with transaction values below $1. This is the domain where subscriptions overcharge light users. This monthly commitment forces light users to pay a minimum subscription fee to start using. x402 can settle each request at machine speed, with granularity down to $0.01, as long as blockchain fees remain feasible.

Two forces make this shift feel urgent. On the supply side, the "tokenization" of work is exploding: LLM tokens, API calls, vector searches, IoT pings. Every meaningful action on the modern web has already attached a tiny, machine-readable unit. On the demand side, SaaS pricing leads to absurd waste. About 40% of licenses are idle because finance teams tend to pay per seat, as this is easy to monitor and predict. We meter work at the technical layer but charge humans at the seat layer.

Event-native billing with caps is a way to align these two worlds without scaring off buyers. We can have soft caps that ultimately reconcile to the best price. A news site or developer API could charge per request all day, then automatically refund to the published daily cap.

If The Economist publishes "0.02 dollars per article, daily cap 2 dollars," a curious reader can browse 180 links without doing mental math.

At midnight, the protocol settles all charges to 2 dollars. The same model applies to developer interfaces. News organizations could charge for each LLM scrape to sustain future AI browser revenue. Search APIs like Algolia could charge $0.0008 per query, totaling $3 for daily usage.

You can already see consumer AI moving in this direction. When you reach Claude's message limit, it doesn't just say, "Limit reached, come back next week." It offers two paths on the same screen: upgrade to a higher subscription or pay per message to complete what you're doing.

What’s missing is a programmable infrastructure that allows agents to automatically make the second choice, paying per request without UI pop-ups, cards, or manual upgrades.

For most B2B tools, the actual end state looks like "subscription base + x402 bursts." Teams retain a basic plan tied to the number of users for collaboration, support, and backend usage. Occasional recalculations (build minutes, vector searches, image generation) are billed through x402, rather than forcing an upgrade to the next tier.

Double Zero aims to sell faster, cleaner internet through dedicated fiber. By routing traffic through them, you can price by gigabyte using x402, with clear SLAs and caps. An agent needing low latency for trading, rendering, or model hopping can temporarily enter the fast lane, paying for that specific burst, and then exit.

SaaS will accelerate the shift to usage-based pricing, but with guardrails:

Customer acquisition and activation costs decrease. You can start making money on the first call. Those occasional developers can still pay $0.03. Agents prefer vendors that can accept instant payments.

Revenue scales with actual usage rather than seat inflation. This is how to cure the 30-50% seat waste in most organizations. Heavy loads shift to capped burst billing.

Pricing becomes a product interface. "Fast lane for an extra $0.002 per request," "half-price batch mode," these are knobs startups can experiment with to increase revenue.

Lock-in effects weaken. With the ability to try vendors without integration effort and time, switching costs decrease.

A World Without Ads

Micro-payments won’t eliminate advertising; they will narrow the domain where advertising is the only viable model. Advertising still performs well in areas of casual intent. x402 prices interfaces that ads cannot reach, where occasional humans might choose to pay for a good article without subscribing for a month.

X402 reduces payment friction; at scale, it could change the future.

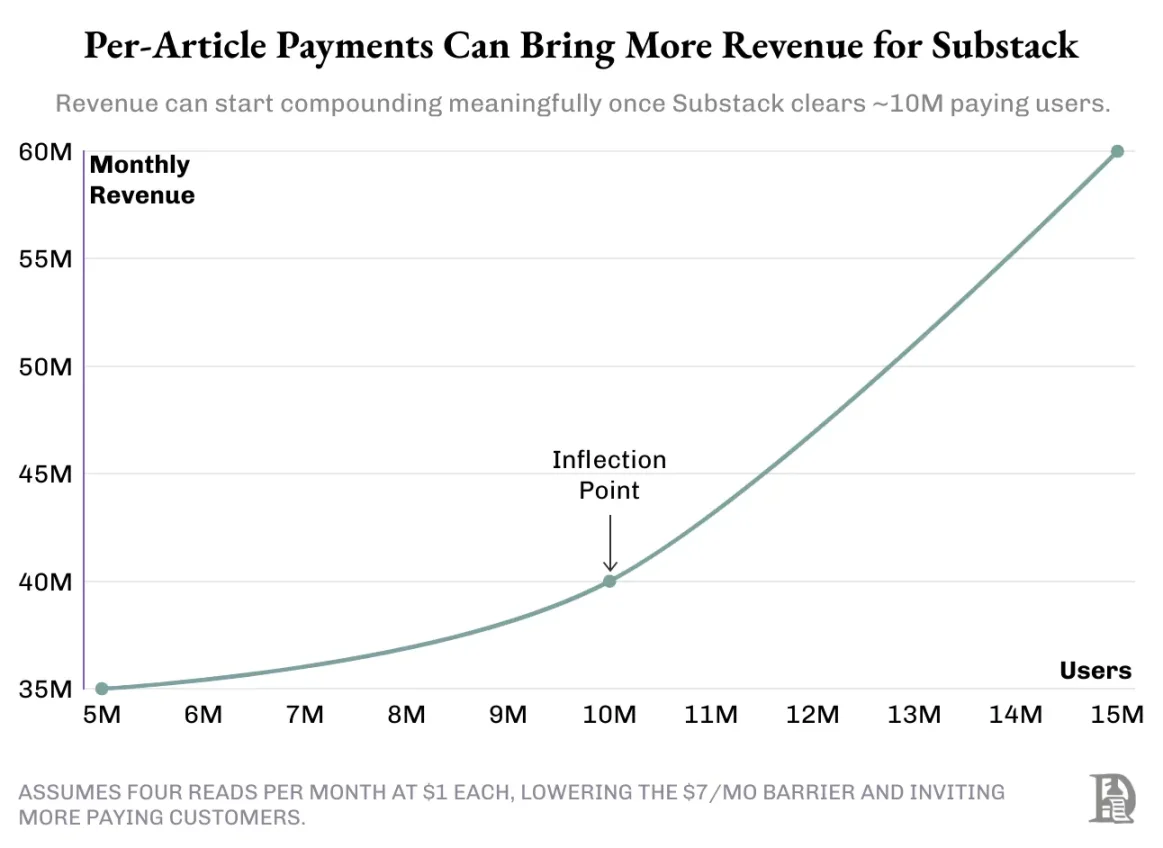

Substack has 50 million users with a 10% conversion rate, meaning 5 million subscribers pay about $7 per month. When the base of paying subscribers doubles to 10 million, that might be when Substack starts to see more revenue from micro-payments. With lower friction, more casual readers can turn to paying per article, accelerating the revenue curve.

The same logic applies to any seller with high variance and low-frequency sales: when people use a product occasionally rather than habitually, paying per use feels more natural than committing to a long-term plan.

It’s a bit like my experience visiting the local badminton court. I play two or three times a week, usually at different places and with different friends. Most of these courts offer monthly memberships, but I don’t like being tied to one location. I enjoy the freedom to decide which court we go to, how often I go, and skipping a session when I’m tired.

Don’t get me wrong; I know this varies by person. Some people prefer to stick to the nearest court, some like having a subscription that encourages them to form a routine, while others might want to share one with friends.

I can’t speak for offline payments, but with x402, this individuality can be reflected in the digital world. Users can set their payment preferences through strategies, and companies can respond with flexible pricing models that adapt to everyone’s habits and choices.

x402 truly shines in agent-based workflows. If the past decade was about transforming humans into logged-in users, the next decade will be about transforming agents into paying customers.

We’ve succeeded halfway. AI routers like Huggingface let you choose among multiple LLMs. OpenAI’s Atlas is an AI browser that runs tasks for you using LLMs. x402 integrates as the missing payment infrastructure in that world. It’s a way for software to settle tiny bills with other software at the precise moment work is completed.

However, just having infrastructure doesn’t create a market. Web2 built a complete scaffolding around card networks. Bank KYC, merchant PCI, PayPal disputes, credit card fraud locks, and chargebacks when things go wrong. Agent-based commerce currently lacks any of these. Stablecoins plus x402 give agents a way to pay, but they also strip away the built-in recourse that people are accustomed to.

When your shopping agent buys the wrong flight, or your research bot runs out of data budget, how do you get your money back?

This will be what we delve into next: how developers can use x402 without worrying about future failures.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。