Author: Citrini, Analyst

Translation: Felix, PANews

Affected by the U.S. tariff increase events, the global economy seems to have entered a state of disorder. Was the Trump administration's tariff increase a stroke of genius or a blunder? Analyst Citrini published an article that reviews historical tariff events from a historical perspective and gradually analyzes the future economic situation. Below is the full content.

“This may be a mistaken viewpoint”

Benjamin Franklin wrote in 1781:

“But I find myself more inclined to adopt a more modern view, that it is best for each country to allow trade to be completely unobstructed. Overall, I just want to point out that commerce is the mutual exchange of necessities and conveniences of life; the freer and less restricted it is, the more prosperous it becomes, and the happier all countries involved will be. The restrictions that countries impose on commerce seem to be carried out under the banner of public interest, but are actually for their own benefit.”

In the two weeks since “Liberation Day” (PANews Note: Trump referred to April 2 as “Liberation Day”_ and announced a global tariff plan)_, I spent a week in the U.S. and a week in China. In both countries, I spoke with entrepreneurs affected by the tariffs.

Whether they are importers or exporters, businesses engaged in varying degrees of international trade in these two vastly different regions share a common point: uncertainty.

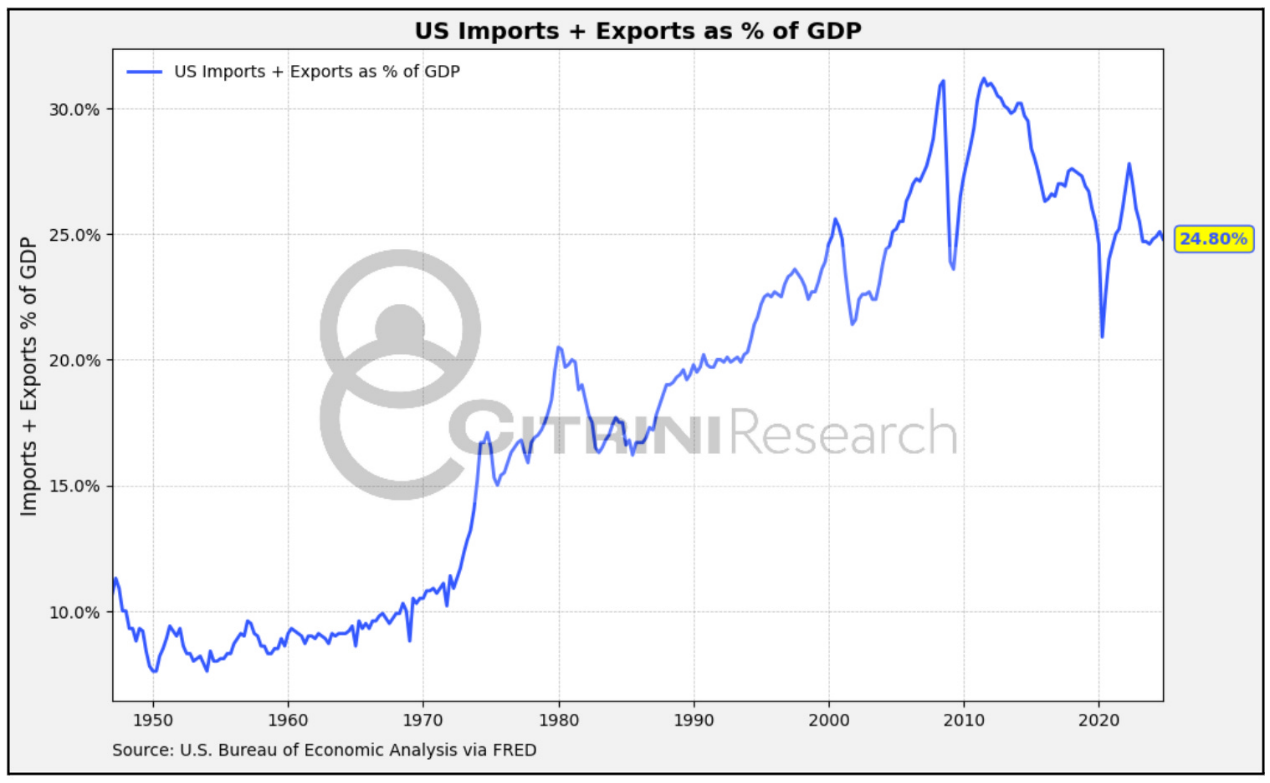

Why is there a sense of uncertainty? A simple fact is that almost everyone today has only experienced a world of increasing globalization, relatively free trade, and the U.S. as the world’s hegemon and reserve currency.

As this is called into question, both investors and operators are clearly seeking frameworks that can cope with the future. For systems built on “just-in-time” principles, “wait-and-see” is a fatal strategy, but there is no other choice.

For example, when talking with a top 100 company in Shanghai (ranked by trade volume), they stated: “We should be ramping up to handle holiday orders now. But currently, we haven’t received a single order.” Anyone unfamiliar with how imported goods operate should realize: first, ordering goods for an event typically requires an 8-month lead time. Second, we are undergoing a significant transition.

Chinese companies have traditionally believed that tariffs are something they can adapt to. In the past, a 10% tariff might lead buyers to seek price reductions from Chinese factories (which was easily achievable). While factories clearly cannot respond to tariffs exceeding 100% by lowering prices, they do believe they can maintain a cost advantage relative to U.S. domestic manufacturing by lowering prices after the tariff increase. But when no one is trading, this becomes irrelevant.

I haven’t published a historical article in over two years. These articles may not necessarily be actionable. But this article seems timely. Sometimes, the only way to understand the future is to understand the past.

Many isms such as mercantilism, isolationism, and protectionism are thrown around haphazardly, yet few care about the meanings behind them. While I am not an economist, I am an enthusiast of economic history. Consider this article as a popular science piece; it does not discuss what stocks to buy or make directional judgments on foreign exchange, stocks, or interest rates.

Understanding Tariffs from a Historical Perspective

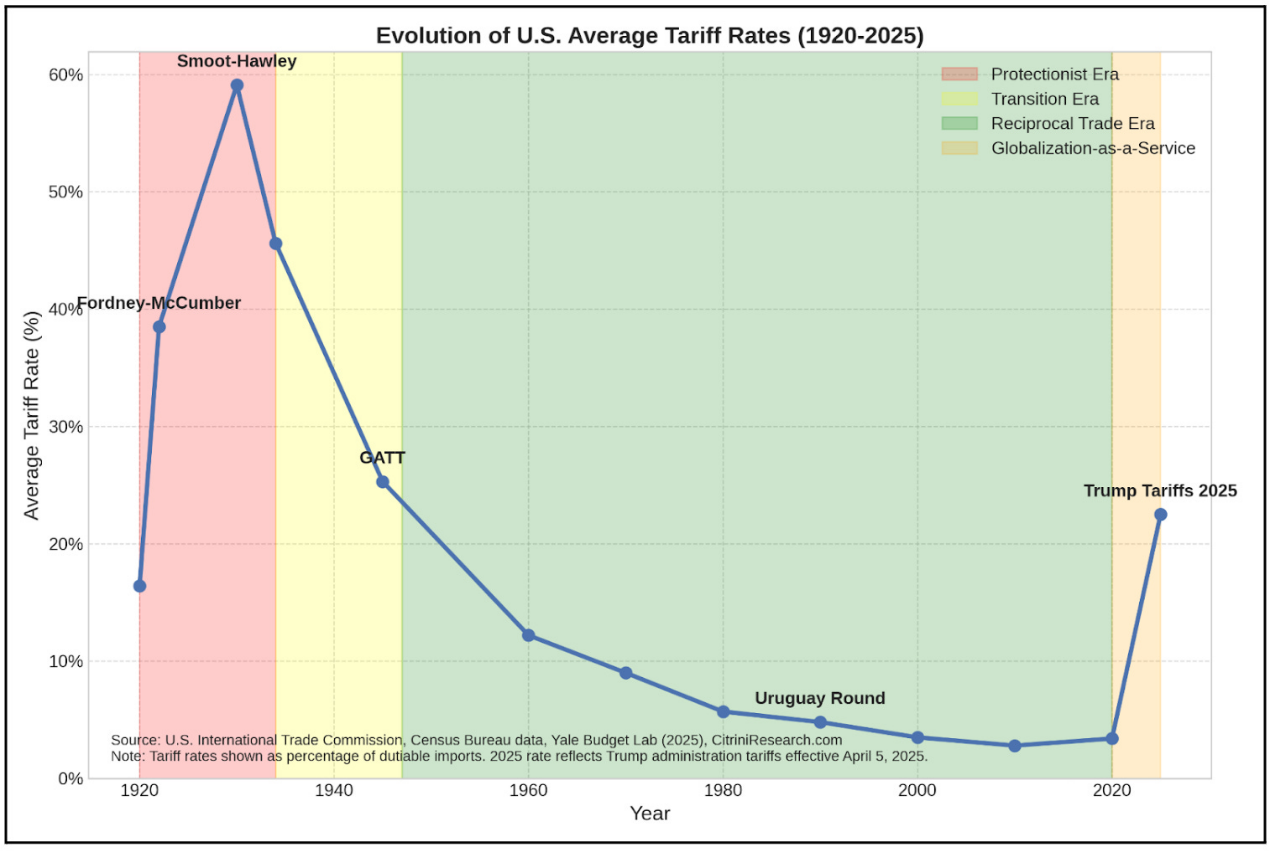

Today, few people have truly experienced economic conditions similar to the current tariff era. The best work exploring the history of U.S. tariffs is “Clashing over Commerce,” which I have been rereading over the past few weeks.

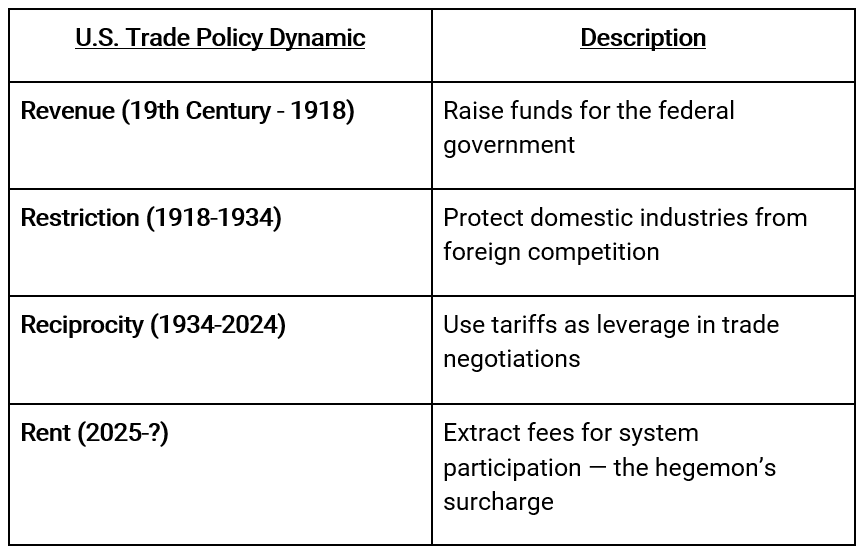

This book, written by renowned historian and economist Douglas Irwin, who studies U.S. trade policy, presents a “3R” framework for understanding the political economy of tariffs.

Historically, the “3R” framework of U.S. tariffs includes:

Revenue

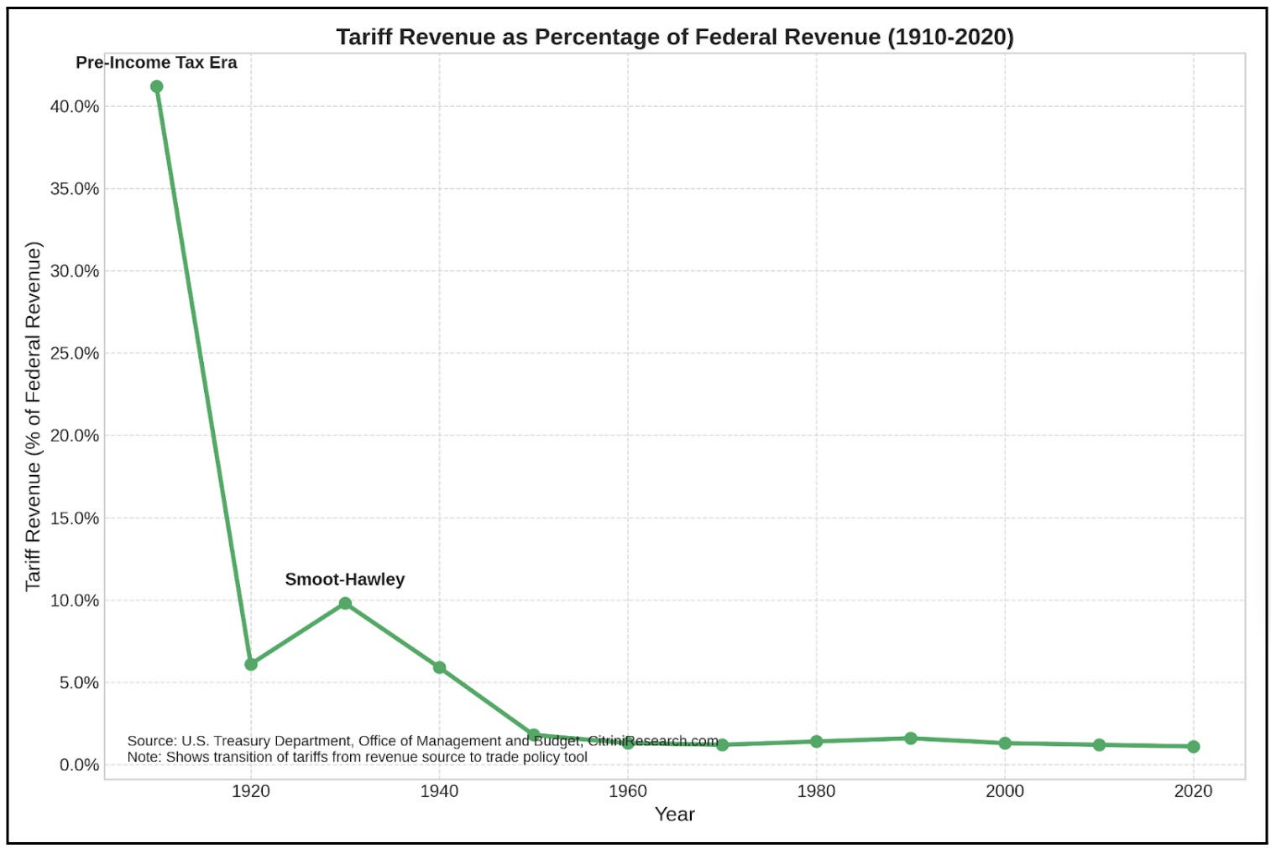

Tariffs have been a major source of government revenue. This was especially true in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Tariff legislation has long been criticized as an opaque and difficult-to-manage policy tool, even though they are a primary source of government funding, as illustrated by this 1883 political cartoon.

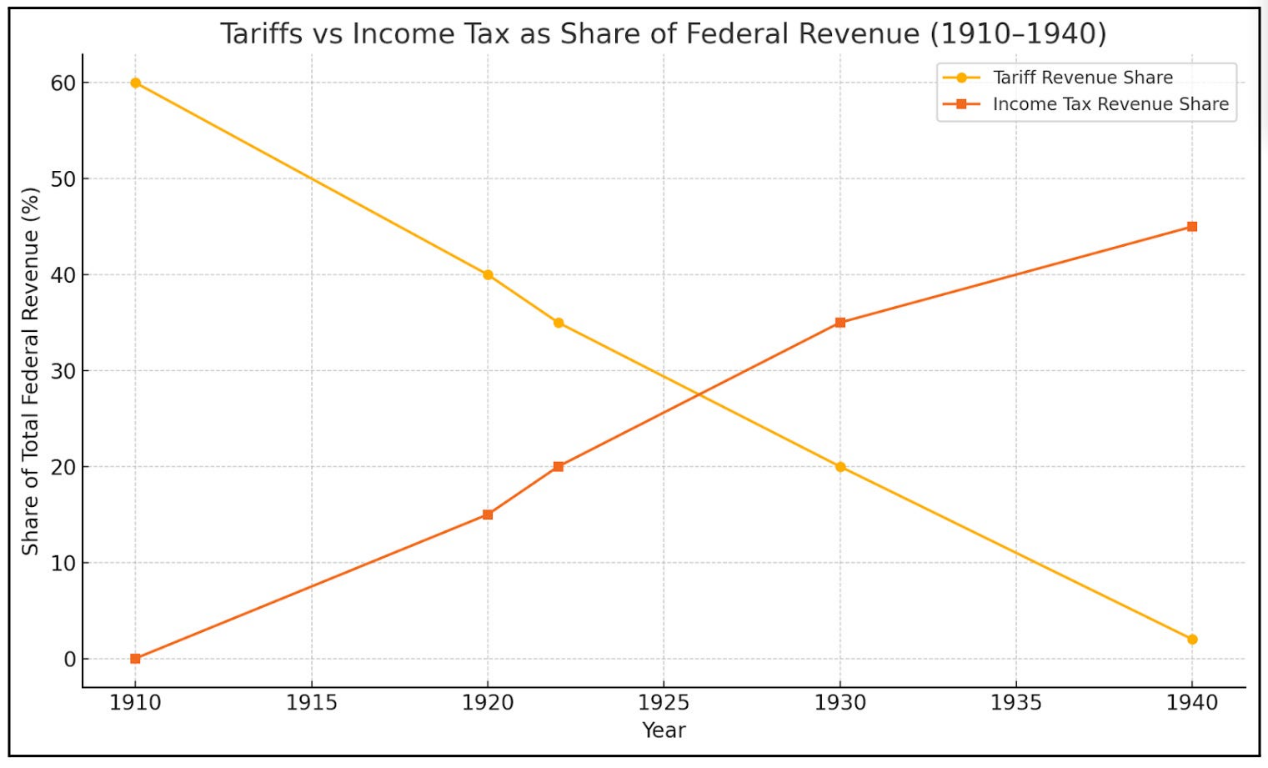

Before the establishment of the IRS (in 1913), there was no income tax in the U.S. In the 19th century, tariffs accounted for over 90% of government revenue. At that time, tariffs were primarily used to increase revenue rather than for protectionism—this was seen as a more acceptable way to tax the public without inciting rebellion. In the first third of the 20th century, less than 15% of American citizens paid income tax. The rest paid invisibly through the prices of imported sugar, timber, and wool. Tariffs were the original hidden tax: collected at the port and paid at checkout.

First, they were a way to fund the nation, avoiding the establishment of internal taxes that could provoke political backlash (a lesson learned from events like the Whiskey Rebellion). In Irwin’s narrative, the revenue issue dominated early trade policy in the Republic, and even arguments for protectionism had to be articulated through a revenue-first perspective.

Restriction

Tariffs protect domestic industries.

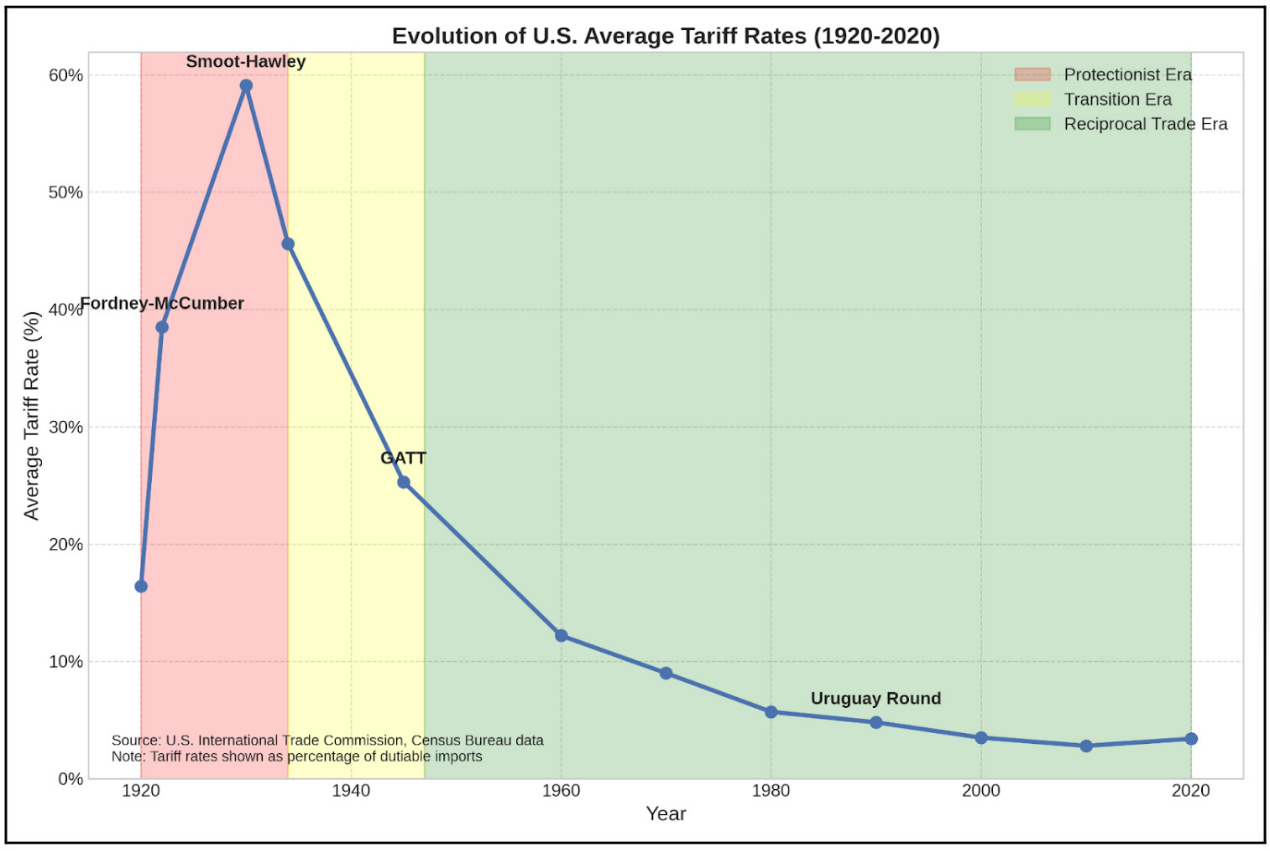

After World War I, tariffs increasingly became a political tool to cater to domestic industries facing foreign competition—the driving force of protectionism.

Irwin points out that as the revenue motivation declined (thanks to income tax), the motivation for restriction increased. After World War I, tariffs increasingly served industrial lobbying groups rather than the Treasury.

Reciprocity

Tariffs are bargaining chips in international trade negotiations.

By 1934, income tax gradually replaced tariffs as the primary source of federal funding—this transition was accelerated by the New Deal and World War II. Tariffs became bargaining chips in global trade negotiations.

This is precisely the logic behind the 1934 Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, and later the World Trade Organization. The era of reciprocity marked a move towards liberalization, breaking free from isolationism. The hegemonic power (the U.S.) lowered tariffs in exchange for access to foreign markets. Tariffs were no longer a barrier but more like leverage. VERs, or Voluntary Export Restraints, which aimed to force countries to implement export restrictions, replaced tariffs and were ultimately supplanted by more and larger free trade agreements. This propelled the arrival of the multilateral free trade era at the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century.

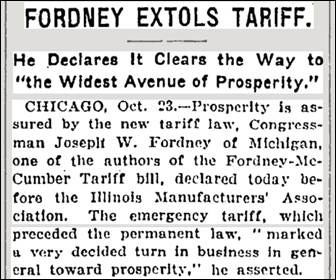

1922: Fordney–McCumber Tariff

The Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act is a prototype of early protectionism taken to excess and the first real case of tariffs being levied for non-fiscal revenue purposes.

Imagine the glorious scene in post-World War I America: abundant industrial output, but farmers increasingly impoverished. The most concerning issue at the time was the cheap competition from Europe, but Europe still owed the U.S. a lot of money, and due to the U.S. continually raising tariffs, Europe could not sell anything to the U.S. at all. So, it was clear that the U.S. raised tariffs again.

In 1921, Congress passed an emergency tariff bill, followed by the comprehensive Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act of 1922, signed by President Warren Harding.

This law significantly raised tariffs, far exceeding the low levels set by the 1913 Underwood Tariff Act and higher than tariff levels since the American Civil War (though the rates on imported goods subject to tariffs were roughly on par with those during the 1909 Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act). Additionally, the law granted the president the power to adjust rates by as much as 50% to “balance domestic and foreign production costs.”

What was the result? Urban industries thrived in the 1920s, while agriculture fell into a prolonged decline, and Europe’s trade surplus gradually shrank, knowing they had to rely on that surplus to repay the goods provided by the U.S. during the war.

For the American industrial sector, the 1920s were a glorious decade. From 1922 to 1929, manufacturing output grew by nearly 50%. The unemployment rate fell from 6.7% in 1922 to 3.2% in 1923. Industries such as steel, chemicals, and automobiles flourished under the protection of tariff barriers. Protected industries expanded, hired more workers, and became profitable. During this period, corporate profits nearly doubled.

However, the situation in agriculture was entirely different. Agricultural income plummeted from $22 billion in 1919 to $13 billion in 1922. While urban areas prospered, rural America fell into a decade-long depression, ten years ahead of the Great Depression. What was the reason? The European market closed in retaliation, while American farmers, who had expanded production during the war, faced plummeting demand and prices.

In the 1920s, protectionism brought concentrated benefits. If you were an urban industrial worker, it was a great time. If you were a farmer, it marked the beginning of twenty years of suffering. The momentum of protectionism had begun, and it achieved a certain level of success for some (though at a high cost to others).

1930: A Misstep

Massive tariffs, massive depression.

In 1928, Herbert Hoover was riding high. The great engineer won the presidential election by an overwhelming margin: he received 444 electoral votes, while Al Smith garnered only 87. Hoover won more counties than Warren Harding did in 1920 and secured 58% of the popular vote. This "prosperity president" promised the American people in his inaugural address to "completely conquer poverty"—yet these words soon became his nightmare.

The stock market soared, unemployment was low, and Americans were purchasing cars, radios, and refrigerators at an unprecedented rate. Since William McKinley's victory in 1896, the Republican-dominated Fourth Party System (PANews _Note: the political ecology of the U.S. from 1896 to 1932) _ seemed as entrenched as ever.

Like his Republican predecessors, Hoover was a staunch advocate of protective tariffs. During his campaign, he declared, "For 70 years, the Republican Party has supported a tariff designed to fully protect American labor, American industry, and American farms from foreign competition." He viewed tariff protection, especially for agriculture, as the cornerstone of his economic agenda.

As Secretary of Commerce under Harding and Coolidge, Hoover developed a clear protectionist ideology: the U.S. should essentially limit imports to products that could not be produced domestically. This was not a radical move but rather the pinnacle of the McKinley Republican tradition, a natural extension of the orthodox economic thought of the Fourth Party System.

Hoover used the "success" of the Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act (which had seen an increase in total U.S. imports since its passage) as evidence that America could protect its industries while expanding sales in Canada. In 1926, he wrote, "Given the vast prospects of our trade, we can ignore the concern that raising tariffs will significantly reduce our total imports, thereby destroying other countries' ability to purchase products from us." In a campaign speech in 1928, he stated, "The idea that we cannot have both protective tariffs and growing foreign trade is baseless. Today, we have both."

Then came "Black Thursday" on October 24, 1929, followed by "Black Tuesday" five days later, when the stock market lost over $30 billion in value—almost double what the U.S. had invested in World War I. The roaring twenties came to a sudden halt. Amid the turmoil, tariff negotiations did not subside; instead, they intensified:

In light of the economic upheaval, Congress not only failed to reconsider tariff legislation but actually doubled down. The initial agricultural tariff bill evolved into what is now known as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, named after its primary sponsors—Senator Reed Smoot of Utah and Representative Willis C. Hawley of Oregon. Originally intended to provide relief for farmers, the bill ultimately morphed into a monstrosity of industrial protectionism.

What began as targeted measures to protect American farmers devolved into a chaotic battle of protectionism. During the congressional deliberations from 1929 to early 1930, the number of protected industries grew exponentially. Ultimately, the bill raised tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods, setting the highest tariff rates in U.S. history since the "Tariff of Abominations" in 1828.

A cartoon depicts a weary Republican elephant sitting in the middle of the road, leaning against a large stone labeled "Tariff Bill".

The market did not buy it. 1,028 economists, despite their differing opinions on how to escape the Great Depression, reached a consensus on one point—if the bill passed, it would be a disaster.

They wrote to Hoover, pleading with him to veto the bill:

Headline news from May 8, 1930.

Thomas Lamont, a partner at J.P. Morgan, later recalled, "I almost knelt down to beg Herbert Hoover to veto the foolish Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act. This bill would exacerbate nationalism around the world."

Henry Ford spent an entire night at the White House trying to persuade Hoover, claiming that the tariff bill would cause severe economic damage.

However, on June 17, 1930, Hoover signed the bill into law. Although political suicide is not instantaneous, this act was enough. The unpopularity of the tariff bill grew rapidly, as evidenced by the frequent letters from readers in The New York Times:

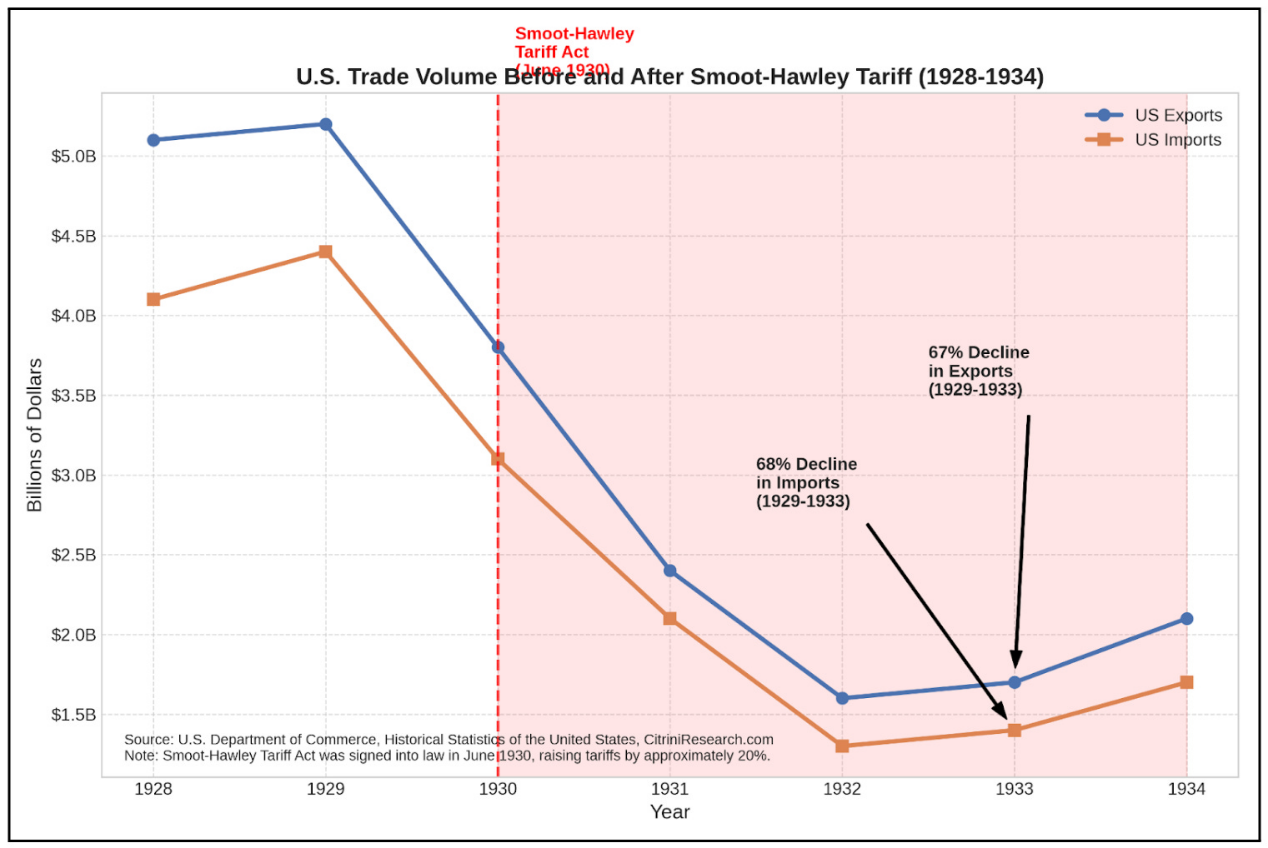

What happened next was as they predicted: over 25 countries took retaliatory actions. Global trade collapsed.

In 1929, U.S. imports totaled $4.4 billion, plummeting to $1.3 billion by 1932. During the same period, exports fell from $5.4 billion to $1.6 billion. From 1929 to 1934, world trade volume decreased by about two-thirds.

The stock market crash of 1929 triggered an economic recession, and tariffs turned this recession into the Great Depression.

What began as a financial shock evolved into a systemic crisis, as policies—especially the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act—stifled supply when demand was already declining.

As economists had predicted, American consumers and businesses paid the price. Tariffs may have protected some jobs in specific industries, but they destroyed more jobs by raising the prices of imported raw materials and closing foreign markets to U.S. exports.

Democrats recognized this disaster and made tariff reform a key campaign platform in the midterm elections of 1930—this was their first control of both houses of Congress since 1918. Roosevelt remarked that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act "forced countries around the world to erect such high tariff barriers that world trade is diminishing to the point of almost disappearing."

The outcome was clear: the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was a complete failure.

What are the differences between the tariffs of 1922 and 1930?

First, from the starting point: the Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act was implemented during a period of relative global economic growth, especially in the U.S. The roaring twenties masked many of its inefficiencies. In contrast, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was passed after the stock market crash of 1929, when global demand was already shrinking. It exacerbated an already dire situation. From a protectionist perspective, tariffs acted as a catalyst for economic recession, but they still required a trigger.

In 1922, businesses and consumers were confident, credit was abundant, and the financial environment was loose. By 1930, bank failures, sharp declines in stock prices, and tight credit had become commonplace. At this time, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was introduced, significantly raising rates and covering as many as 20,000 types of goods, which undoubtedly worsened the situation, indicating that the government had adopted a reckless policy at a critical moment, leading to increased panic among investors worried about further escalation of protectionism.

Second, retaliatory measures. The Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act triggered some limited retaliatory actions (such as measures taken by France in 1928 and selective tariffs imposed by some European countries), but global trade continued to expand in the 1920s. The damage caused by the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act can be easily measured by its direct economic impact—raising the average tariff on imported goods subject to tariffs in the U.S. to 59.1%, the highest level since 1830. However, the real disaster was not the tariffs themselves but the global retaliatory actions they provoked.

Canada was then the largest trading partner of the U.S., and it had not taken significant retaliatory actions against the U.S.'s tariff increases. The Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act raised tariffs on important Canadian exports such as wheat, cattle, and milk, but Canadian producers viewed these as merely a return to pre-World War I levels, which they could tolerate.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was different. At that time, the global economic recession was intensifying, and Canadian exports had already been severely impacted. In July 1930, shortly after the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was passed, the Canadian Liberal government lost the election to Conservative leader Richard Bennett. Bennett fulfilled his campaign promise to "force" open world markets by raising tariffs. Pushing other countries into a corner made their reactions increasingly unpredictable.

In September 1930, Canada significantly raised tariffs on 16 U.S. products, which accounted for about 30% of U.S. exports to Canada. Canada also negotiated preferential trade agreements with other Commonwealth countries, further undermining the competitiveness of U.S. export products.

Retaliatory actions did not stop with Canada. By 1932, at least 25 countries had taken retaliatory measures against U.S. goods. Spain specifically targeted American cars and tires with the "Wes Tariff." Switzerland boycotted American products. France and Italy imposed quota restrictions on American goods. The United Kingdom abandoned its traditional free trade policy and also adopted protectionist measures. This led to a worsening situation, with global trade stagnating due to uncertainty and escalating tit-for-tat trade policies.

Third, global financial conditions. In 1922, the U.S. was still an emerging creditor nation, but the gold standard had not yet been fully restored, and many countries were still recovering from World War I. There was no tightly integrated global financial system at that time. However, by 1930, the gold standard had been reestablished globally. The connections between international trade and debt flows became tighter.

Finally, from a symbolic perspective, while the Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act was a poor policy, it was also expected. Tariffs had been the norm in the U.S. since the Civil War, and many trading partners viewed the Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act as merely a return to pre-World War I levels. In contrast, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was seen as an escalation at a time when the world was clearly vulnerable. It indicated that the U.S., having solidified its status as a creditor nation, was turning towards an inward-looking economy. It undermined confidence in global coordination and may have prompted many countries to abandon the gold standard shortly thereafter.

Markets and policymakers interpreted the Smoot Act not just as a tariff issue but as a worldview: isolationism, chaos, and irrationality. Uncertainty suppressed business investment.

This was a unique and unprecedented disaster during the era of protectionist trade policies, paving the way for Roosevelt's election. Roosevelt quickly abolished tariffs and passed the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA).

1934: RTAA—The Beginning of Reciprocity

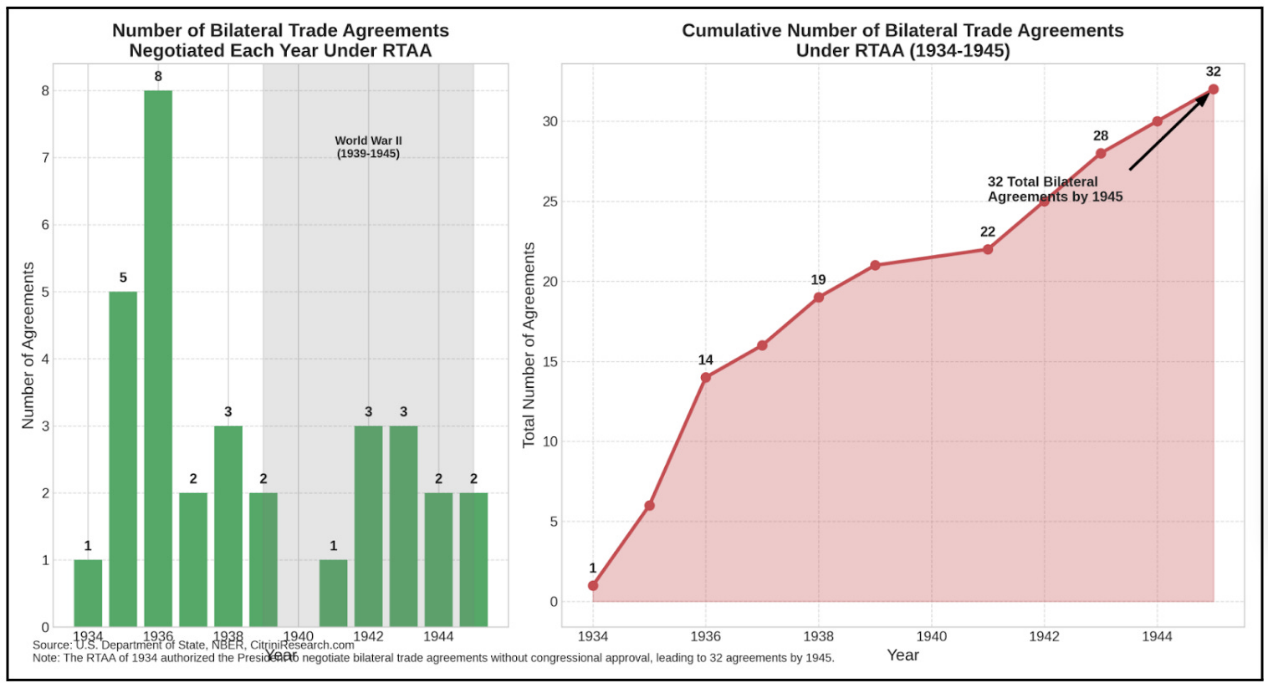

In the aftermath of the protectionist disaster triggered by the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, U.S. trade policy reached a crossroads. The introduction of the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act in 1934 marked a shift in the power to determine trade policy from Congress to the executive branch, initiating a transition from "restriction" to "reciprocity." This institutional change fundamentally altered the way trade policy was formulated and laid the groundwork for a more liberal trading system after World War II.

The history of modern international trade begins with Cordell Hull, a Democrat from Tennessee who later became the longest-serving Secretary of State in U.S. history. Hull's background in the agriculturally rich South profoundly influenced his views on tariffs and trade. Unlike his Northern colleagues who sought to protect manufacturing, Hull understood that high tariffs would harm agricultural exports.

Signing the U.S.-Canada Trade Agreement. (Front row, left to right): Cordell Hull, W.L. Mackenzie King, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Washington D.C.

November 16, 1935

Hull's understanding of trade on an international level developed gradually. He later recalled that before serving in Washington, he "had personally experienced fierce tariff battles—but these battles were fought domestically, debating whether high or low tariffs were good or bad for the country. Few considered their impact on other countries."

The Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act emerged from the ruins of the failure of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. As a protectionist measure, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act prompted countries to impose retaliatory tariffs, severely hindering the development of world trade, while the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act opened a new path for international cooperation. It introduced three revolutionary concepts that would define the era of reciprocal trade:

- Executive Power: For nearly 150 years, Congress had carefully guarded its constitutionally granted power to "regulate foreign trade," leading to trade policy being influenced by local interests. The Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act transferred significant negotiating authority to the president, allowing the president to reduce tariffs by up to 50% without individual congressional approval.

- Bilateral Reductions: The act allowed targeted negotiations with individual trading partners, creating a more strategic pathway for trade liberalization and granting equal standing to export industries and import-competing industries at the negotiating table.

- Most-Favored-Nation Clause: Any tariff reductions negotiated with one country would automatically apply to all countries with which the U.S. had trade agreements, creating a ripple effect and accelerating the process of global trade liberalization.

While the act initially focused on bilateral agreements, it created a template that later served as a reference for the international trade framework.

1947: The Bretton Woods System and GATT—Rules for a War-Torn World

With the end of World War II, the architects of the post-war economic order gathered at a resort hotel in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. The Washington Hotel at Bretton Woods would name the system they designed—this framework aimed to prevent economic nationalism and financial instability, the very factors that had caused the war.

The Bretton Woods Conference held in July 1944 brought together 730 representatives from 44 Allied nations for three weeks of intense negotiations. The conference reflected two competing visions for the post-war economic order. One side was represented by British economist John Maynard Keynes, who spoke for a war-torn Britain now reliant on U.S. financial aid. The other side was represented by Harry Dexter White, who spoke for the now economically powerful United States.

Keynes proposed an ambitious "International Clearing Union" plan that would establish a global currency (which he called "bancor") capable of automatically balancing trade and preventing excessive surpluses or deficits. White's plan was more conservative, establishing rules for exchange rate stability based on the dollar and gold at $35 an ounce while preserving national currency sovereignty.

White's proposal largely prevailed, but it made important concessions to Keynes's concerns about flexibility in adjustments. The final agreement established two key institutions: the International Monetary Fund (IMF), responsible for monitoring exchange rates and providing short-term financing to countries facing balance of payments difficulties; and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, now part of the World Bank), responsible for promoting reconstruction and development through long-term loans.

The Bretton Woods system represented a compromise between the rigidity of the gold standard before 1914 and the chaos of currency wars during the two world wars. Countries would maintain fixed but adjustable exchange rates against the dollar, which served as the anchor of the system through its link to gold. The IMF would provide short-term financing to countries facing temporary balance of payments issues, allowing them to adjust without immediately resorting to austerity measures or competitive currency devaluations.

The system was designed to prevent the catastrophic economic nationalism of the 1930s. By providing liquidity and assistance, the system aimed to give countries breathing room to maintain domestic economic stability and international cooperation. The architects of the Bretton Woods system understood that the choice between domestic economic goals and international obligations had torn apart the economic system during the two world wars. Crucially, they recognized that monetary stability alone was insufficient.

A complementary trade framework was needed. This was reflected in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) signed in 1947.

While the U.S. and the U.K. reached an agreement within the framework of the system, there were disagreements on core issues. The U.S. wanted to eliminate the British imperial preference system. The U.K. sought significant tariff reductions from the U.S., as these tariffs had remained high since the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. What was the compromise? Multilateralism, downplaying political influence and diffusing pressure from all sides.

The core pillars were:

- Most-Favored-Nation Treatment (MFN): Every trade concession made to one member must apply to all member countries.

- Tariff Constraints: Once tariffs are reduced, they cannot be raised without compensation.

- Elimination of Quotas (in most cases): Because nothing exemplifies "central planning" more than restrictions on chicken imports.

In the following decades, a series of negotiations under GATT (Geneva, Torquay, Dillon, Kennedy, Tokyo, Uruguay) gradually reduced global tariffs, transforming the temporary peace of the post-war period into a well-functioning world order. By 1994, GATT was renamed the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the global average tariff fell from 22% to below 4%. From an initial 23 founding signatories, it gradually expanded to include most of the world's trading nations, witnessing a dramatic expansion of international trade in the decades following the war.

The brilliance of GATT lay in its simplicity. It viewed tariffs as weapons: dangerous to use, and retaliatory actions could be contagious. The core principle of GATT was that not all trade is beneficial, but any retaliatory protectionism is detrimental. In essence, it was a behavioral contract: no more weaponized tariffs. No more trade collapses. If you want to raise barriers, you must pay a price. If you reach an agreement, you must share.

Because of this, GATT surprisingly endured over time. For decades, its effectiveness was simple: when it failed, everyone remembered what happened.

However, it turned out that the Bretton Woods monetary system had weak resilience. Faced with persistent balance of payments deficits and declining gold reserves, President Nixon suspended the convertibility of the dollar into gold in August 1971, effectively ending the fixed exchange rate Bretton Woods system.

1971: The End of Dollar-Gold Convertibility

From the Age of Exploration to the Colonial Era (approximately 1400 to the mid-1900s), gold and silver widely served as currencies for international trade settlements. In particular, Spanish dollars were most commonly used for international trade settlements (the term "dollar" is derived from silver mines). Generally, a currency system based on promissory notes may work well locally (where trust and enforcement are feasible), but it does not function internationally.

For example, during the Golden Age of Piracy, the Caribbean was a melting pot for European colonial empires (Britain, France, and the Netherlands), all of which used Spanish dollars for trade settlements. The Spanish Empire was the largest source of silver and minted standardized, ubiquitous silver coins. Even on the other side of the globe, China only accepted silver (especially Spanish dollars) in exchange for tea sold to Britain.

During the period when the pound (backed by gold) was the primary reserve currency, the U.S. became the world's largest economy during the industrial revolution of the late 19th century and recognized as a military superpower in 1944. After 1971, the dollar became the first true fiat global reserve currency. It can be understood that, under the winner-takes-all network effect, the dollar became and continues to be the dominant global reserve currency.

The impact of this on the U.S. economy is not difficult to understand:

Given that gold and silver deposits are found worldwide, even under the Bretton Woods system, no single country was the sole source of global reserve assets. Under the Bretton Woods system (1944-1971), national currencies were pegged to the dollar, which could be exchanged for gold at a fixed rate. Therefore, in addition to gold itself, the pound and Swiss franc also served as functional substitutes for reserve assets.

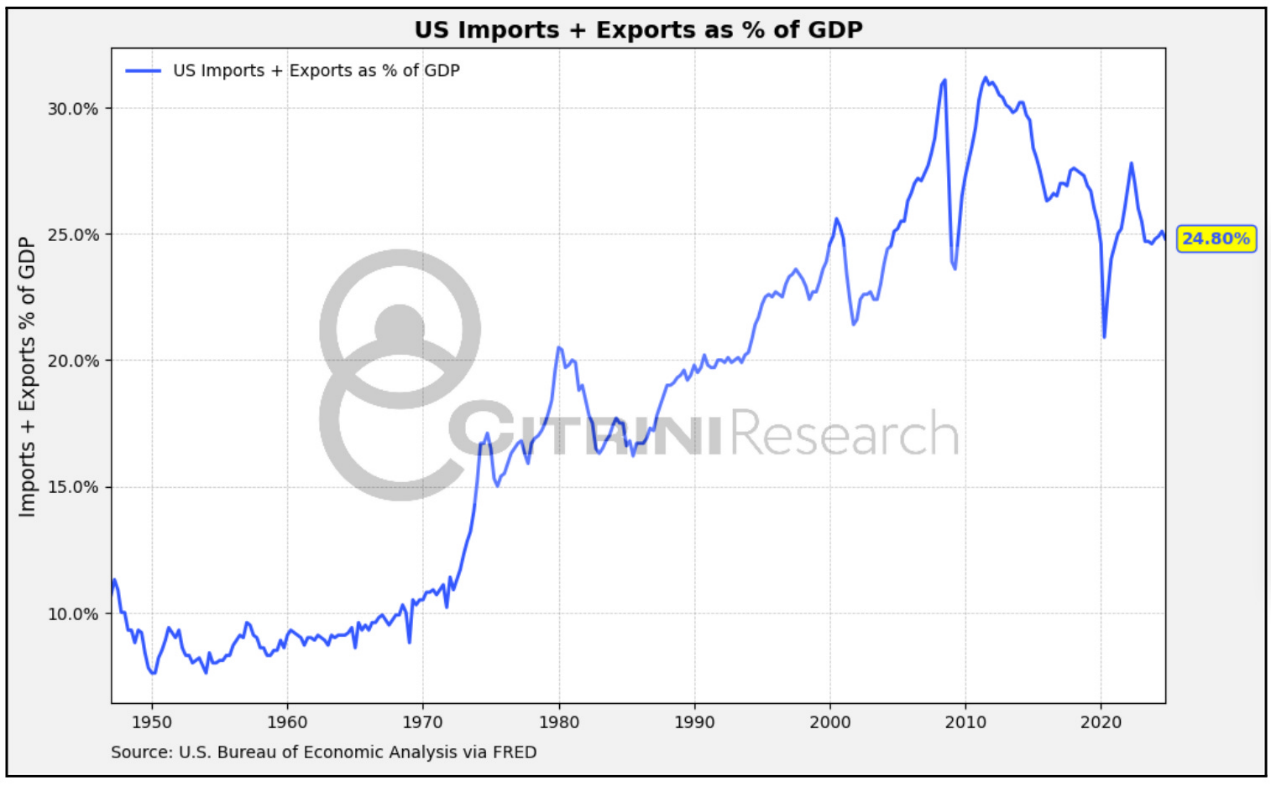

Surprisingly, the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 actually solidified the dollar's status as the world's reserve currency. As the sole source of a major reserve currency, the U.S. ultimately found itself in a dynamic of persistent trade deficits to provide liquid reserve assets to the rest of the world. This seems counterintuitive, as initially, the dollar was abandoned in favor of "real" assets—gold. In the 1980s, Volcker reestablished the dollar's position as the world reserve currency. By 1980, gold was no longer a one-way bet against the dollar. It was "exposed" as an unstable commodity susceptible to speculative booms and busts—not a stable store of purchasing power. Since the 1980s, the U.S. has struggled to achieve a trade surplus (given that other regions of the world naturally tend to accumulate financial wealth denominated in reserve currencies).

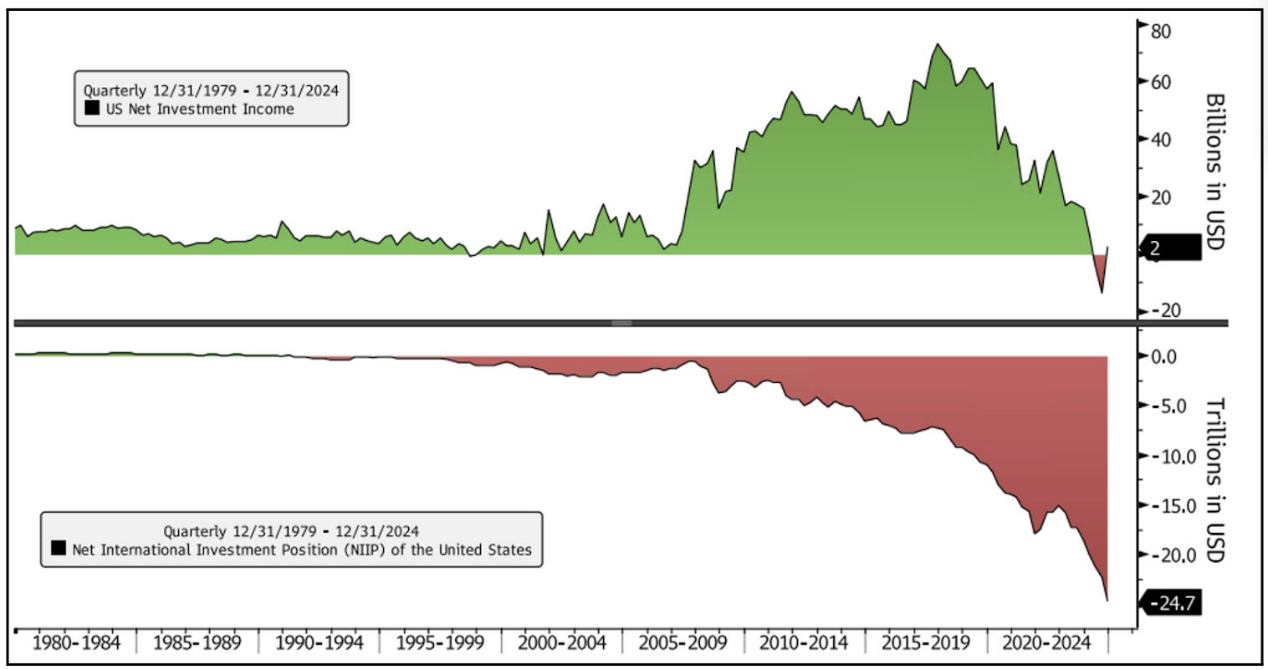

However, the dollar's status as a reserve currency has not been without benefits for the U.S. The concept of "exorbitant privilege" means that, although the U.S. holds more foreign assets than foreign countries hold in U.S. assets, the U.S. actually earns more from its overseas investments. This is because a significant portion of the assets held abroad by the U.S. exists in the form of high-quality, low-yield dollar-denominated balances and fixed-income securities (such as U.S. Treasury bonds, agency MBS, etc.).

When there is international trust and enforcement (which has been the case for decades), a promissory note-based fiat system can function globally, but the global order of U.S. hegemony is now being questioned—not by other countries, but by the U.S. itself.

How Will the Future Develop?

While the world has undergone tremendous changes since the era of reciprocity after World War II, the fundamental contradictions that shape U.S. tariff history remain. Today is at a turning point similar to those in 1930, 1947, and 1971 that changed trade policy. Just as those turning points were driven by shifts in the U.S.'s position in the global order, today's tariff resurgence reflects another adjustment of economic power. However, there is a key difference: the U.S. is actively breaking the system it constructed.

This crisis will not end in three months.

Everything the U.S. does in the next three months is not aimed at alleviating the trade burden or returning to a reasonable model (such as a 10% across-the-board tariff and targeted reciprocal policies), which would be the first shot. The focus will be on isolating China, attempting to force it to the negotiating table. If you do not stand with us, you are against us.

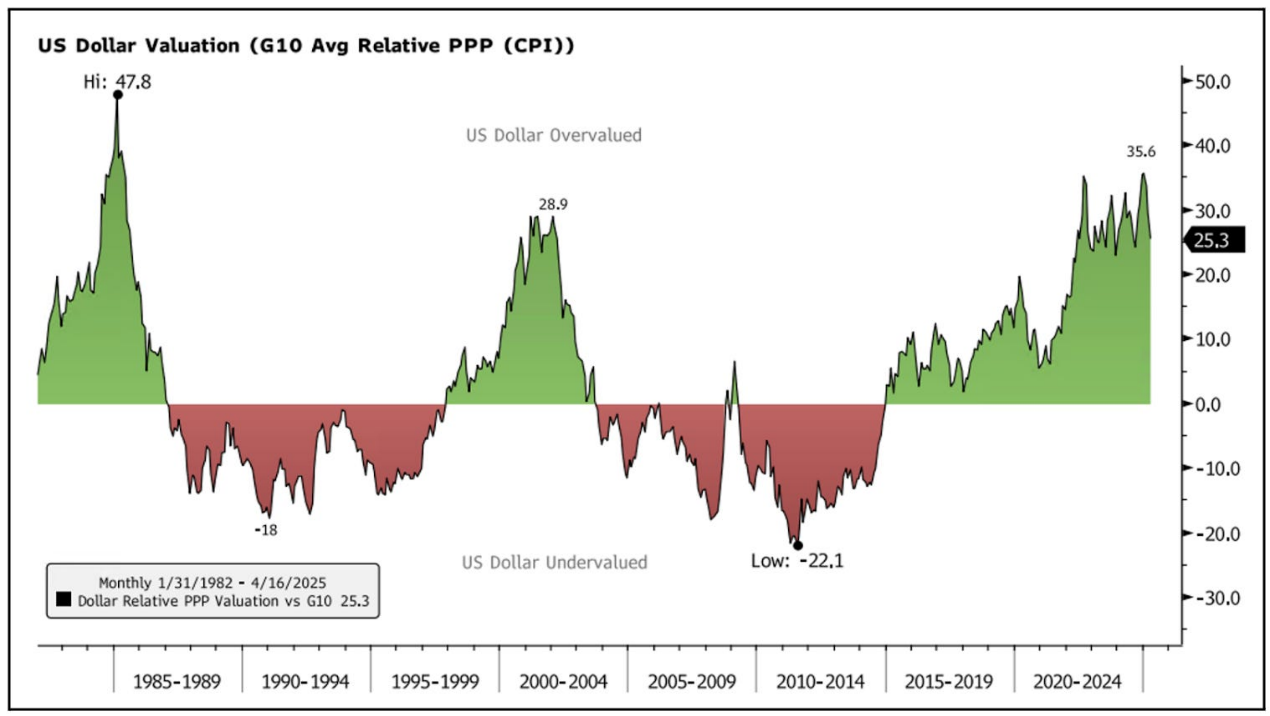

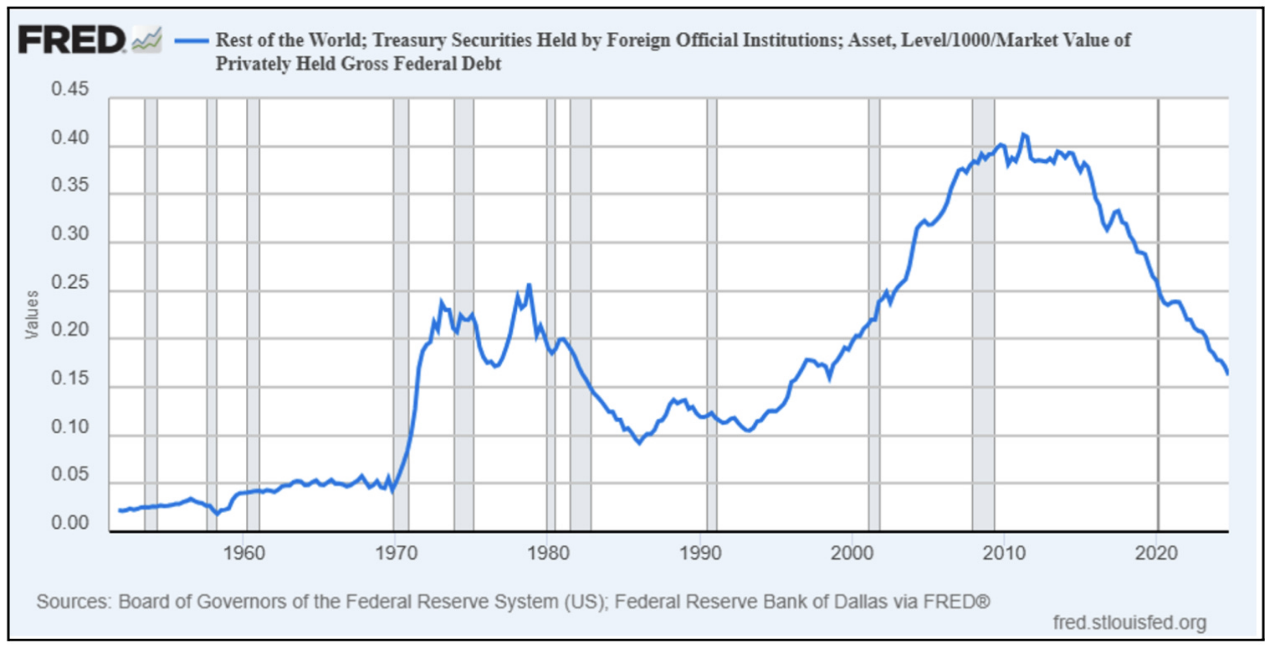

The U.S. has a stockpile equivalent to 2-3 months of inventory, sufficient to offset or distort the initial impact of the global trade disruption. As these inventories deplete, the true effects of the global trade freeze and its subsequent repercussions will begin to be witnessed. Foreign exchange reserve management agencies will continue to reduce their investments in the dollar, as the dollar has entered a long-term bear market.

The suspension of tariff increases is a tactical posture in ongoing negotiations. The likelihood of the U.S. reaching a permanent solution with China in the next 2-3 months is low, but trade negotiations with Europe and even Latin American countries may see some indirect progress. The market interprets this as a measure to ease tensions, but the reality is that it exacerbates uncertainty in the business environment. To survive in the next 90 days, it must be clear…

How to Understand the Government's Perspective?

In this context, understanding the government's perspective will be beneficial. In Trump's view, U.S. hegemony and reserve currency status represent an unfair treatment for the U.S.—not only has it lost its edge in trade and manufacturing, but it also maintains the global trading system "for free." Therefore, the current U.S. position can be roughly summarized as:

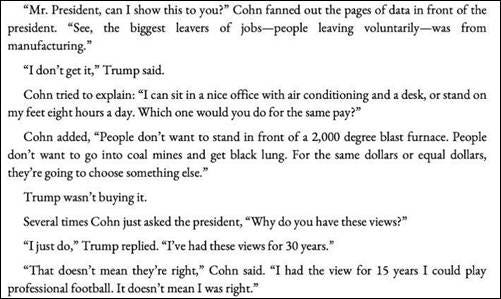

What is truly strange is not the use of tariffs; that is not surprising. Trump has been keen on tariffs for decades, and if you are surprised that tariffs are being imposed on "tariff people," you might want to reconsider your position.

What is surprising is that these three "Rs" have returned simultaneously yet still fail to present the full picture.

Revenue, appearing as fiscal income in the form of billions of new federal revenue, is not labeled as a tax increase, but it is essentially no different from a tax increase.

Restrictions are not only an industrial strategy but also a populist aesthetic—a wall built at the port rather than the border, applicable to everything.

Reciprocity has shifted from mutual barrier relaxation to a grudge match calculated by trade deficits.

Additionally, other factors are at play; this is not merely a revenue issue but one unique to this practice and the globalized world in which it occurs. An additional "R" needs to be added to define the changes represented by this seemingly simple tariff increase. Because we are not truly returning to past dynamics; we are entering a whole new situation.

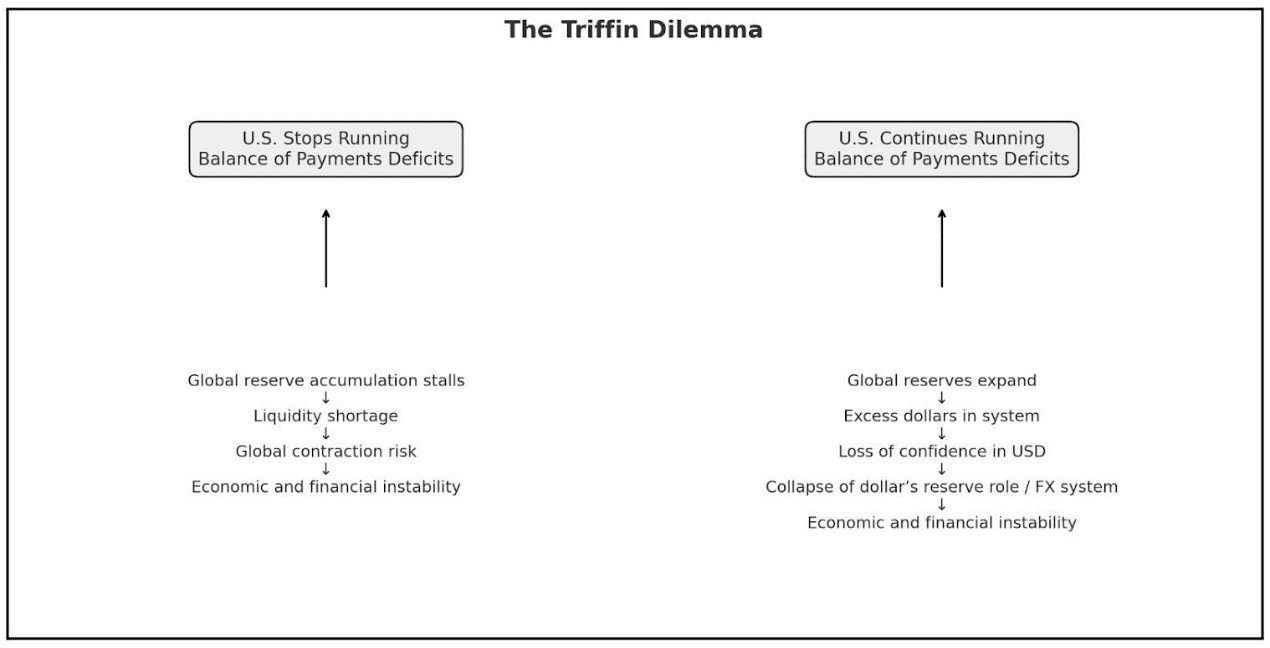

To achieve this, it is essential to fully understand the government's viewpoint. In our article "Seeing the Stag" two weeks ago, we mentioned the challenges of attempting to rebalance global trade by targeting the trade deficits of other countries. The "Triffin Dilemma" describes the paradox faced by a reserve currency country (which had already appeared before the end of the dollar's convertibility into gold). This paradox is as follows:

"Providing reserves and exchange services for the entire world is indeed a heavy burden for a country and a currency." Henry H. Fowler (U.S. Secretary of the Treasury)

Unsurprisingly, the Trump administration's interpretation of the "Triffin Dilemma" is less about the IMF's white paper and more about the bill. They believe the U.S. has been exploited, forced to bear trade surpluses, and they want to correct this phenomenon. Imposing tariffs on the trade deficits of various countries clearly indicates their priorities and concerns.

From the Trump administration's perspective, what is happening or has happened in the existing system is:

- Foreign central banks purchase dollars not out of preference but out of obligation—because if you want to lower your currency's exchange rate and increase exports, you need to accumulate dollars.

- Those dollars are deposited in U.S. Treasury bonds, which conveniently fund the same U.S. government that complains about being taken advantage of.

- The dollar remains structurally overvalued, a direct consequence of the dollar serving as a savings account and lifeboat for everyone else.

- U.S. manufacturing has been hollowed out, not because China cheats, but because the U.S. plays the role of system administrator in a network it cannot fully control.

- Ultimately, trade deficits continue to worsen; Trump dislikes the term "deficit" and the idea of being the world's largest "debtor nation." The role of the reserve currency is beginning to be viewed as a liability rather than a privilege.

From this perspective, tariffs are not merely about protecting factories or funding the government. They are overdue fees for system maintenance. In fact, they are akin to geopolitical "rent," equivalent to forgetting to unsubscribe yet having to pay $14.99 a month. More simply put, the government's viewpoint is:

"We manage this system—regulating flows, ensuring safe passage, purchasing your export products, issuing your reserve assets. Now we are going to charge you for it."

The Fourth R: Rent

Rent redefines tariffs as a service charge model for global economic participation, rather than a means of funding the state (revenue), protecting domestic producers (restrictions), or ensuring reciprocal access (reciprocity). This new model essentially…

Globalization as a Service

Tariffs, NATO threats, opposition to foreign acquisitions, etc., are forming a deliberately crafted pattern: using all available means to extract national wealth from foreign dependencies. Even if this approach undermines global trade and the dollar's status as a reserve asset.

Tariffs are a blunt tool, and Trump is clearly using them as part of a broader negotiation, attempting to upend this system. The 125% tariff rate on China is the most obvious example. Such high tariffs will lead to trade disruptions. So why not use sanctions or quotas? Because it is crucial to start negotiations from the perspective of "paying fees."

The negotiations for a 90-day tariff suspension could yield various outcomes. The main focus will be on forming a coalition to force China to the negotiating table, but discussions about imposing this "fee" in a more lasting manner may also begin to emerge.

How Will Rent Be Paid?

I have always been skeptical about the idea of a "Mar-a-Lago" agreement, and it seems highly unlikely to materialize. However, the discussion of the proposed issuance of century bonds may have unexpected negative consequences, but it illustrates how the fourth "R" (rent) operates.

The idea is that by issuing century bonds with negative real interest rates and encouraging (or forcing) countries to swap their existing long-term bonds for newly issued ones, the U.S. could gain additional economic benefits from maintaining its status as the world's reserve currency and global trade facilitator.

Although its effects are unpredictable and could be chaotic, damaging the U.S.'s credibility and severely disrupting the yield curve, Trump may be eager to eliminate (or significantly reduce) tariffs for countries that agree to convert their bonds into century bonds with negative real interest rates. After all, he has spent his life restructuring and refinancing debts for various entities under the Trump umbrella.

This is just one example, and a rather unlikely one at that. Stephen Miller recently stated that he does not advocate for this idea. But the fact is, Trump is challenging the existing international rules of the game and questioning the role of the dollar and U.S. Treasury bonds. Why? Because he is solely focused on the current situation's impact on U.S. finances. This perspective carries the risk of seeing the trees but not the forest.

If the U.S. were to actually default on foreign-held Treasury bonds in the context of hostile century bond issuance/swaps, it could lead to a rise in gold prices and a decline in the dollar. The impact on the yield curve would be significant. Even without such a scenario, official foreign exchange reserve assets seem likely to further diversify, shifting towards gold, euros, francs, and yen. Moreover, there is a possibility of agreements being reached to settle trade in currencies other than the dollar.

In light of this potential reality, it is not surprising that the official holdings of U.S. Treasury bonds by various countries have been declining for years:

Current U.S. policies can easily be viewed by other countries as extortion. This economic marginal policy is inherently risky. If it fails, it would be akin to the U.S. being both the bank and the client, borrowing from the bank… and then deciding to default.

But the fact remains: countries are still negotiating with a party that is ready to destroy the entire system, regardless of the consequences. It is not hard to see how many countries would prefer to submit rather than face a de-globalized world and its dilemmas.

Could this situation yield results that do not severely damage the global economy? Yes, but there will be no quick restoration of global trust in the U.S.

Regardless of how negotiations progress, it is clear that trade policy will be a major driver of cross-asset returns and economic growth this year. It is evident that we are witnessing a systemic transformation that will impact the macroeconomy for years to come.

In this new regime, tariffs are less about policy and more about precedent. The U.S. has indicated that it will treat market access as a regulator, tightening or loosening trade conditions based on geopolitical compliance rather than economic efficiency. Whether the government proposes large-scale tax cuts or other supportive measures will ultimately depend on the pace and manner of U.S.-China trade negotiations.

Nothing is more important than this right now. The U.S. and China have rapidly experienced a spiral of retaliation from the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, reaching as high as 145%.

Therefore, even though the circumstances and environment are vastly different, it is not hard to understand the feelings of those desperate economists and bankers in 1930 when they witnessed the outbreak of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act trade war. Globalization has become somewhat akin to economic mutual destruction. There may be "winners." Perhaps one country is only 80% destroyed while others are completely obliterated. But is this really the world we want?

Unlike the Hoover administration, the Trump administration faces the contradiction of being both a debtor nation and a trade-restricting nation. While both disregarded economists' warnings and attempted to maintain America's status through tariffs, Hoover's policies were primarily defensive (and misguided) measures aimed at protecting American industry, whereas today's approach includes additional aggressive factors: deliberately using America's status as a debtor nation as leverage, transforming the global trade and financial system from a public good into a private toll road.

While it may be tempting to return to a time when tariffs were so high and say, "Well, this situation may repeat itself," doing so is problematic.

The Return of the Tariff Nation?

We are no longer in the 1890s or the 1930s. Today's world is globalized and integrated, never having attempted to re-separate.

We are not far from an event that profoundly makes us realize how interconnected the world has become. The pandemic not only caused destruction but also revealed the truth. It starkly showed us how fragile the global trade architecture has become. Ships were idled, semiconductors disappeared, and the strong illusion of supply chains was shattered.

I believe we cannot simply… dismantle supply chains. I also believe that the U.S. cannot escape the just-in-time, on-site, and barely resilient systems that have been designed over decades through the imposition of tariffs. Trump's trade policy is not the Smoot-Hawley Act, despite many attempts to draw parallels.

I believe we cannot… easily dismantle supply chains. I also do not think the U.S. can extricate itself from the just-in-time, on-site, and nearly inflexible systems that have been designed over decades through tariff measures. No matter how many people try to compare it to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, Trump's trade policy is not the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act.

What is most unsettling about this is the lack of a historical reference framework. You can draw lessons from the events of the 1970s, the 1930s, and any other events that reshaped the underlying architecture of the system, but that does not explain everything.

In the 1930s, there was no de-globalization phenomenon because the level of globalization was still very low at that time. Today, we are witnessing a superpower actively inserting a stick into the spokes of the globalization wheel it has created.

The key is: it may work. Just temporarily, politically. Until it fails.

Just like the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was effective for about three months—until Canada retaliated, Europe raised tariffs again, and global trade fell into a trap. And American farmers went bankrupt in record numbers yet still voted for those who depressed their agricultural prices.

Today's tariffs may differ in form, but they are functionally the same. They are all based on the same belief: that stability can be achieved by dismantling complexity. Unfortunately, complexity does not yield easily.

To be frank: no one can fully understand how our complex and ever-changing global system operates in real-time. The Federal Reserve cannot, CEOs cannot, the International Monetary Fund cannot, and certainly, neither you nor I can. The chain reactions are fundamentally incomprehensible. However, if we continue on our current trajectory, our collective understanding of it seems only to be enhanced in the most unsettling ways.

This raises a straightforward question:

In a world where rules may change next quarter, how can a company commit to a 30-year, capital-intensive investment?

In an atmosphere where tariffs are not policy but depend on the next tweet, the next election, or the next wave of populism?

This is not just a trade issue; it is a capital formation issue. Long-term investments can only exist under a rare combination of circumstances: predictability and trust in institutions are the two most significant factors.

Although the U.S. market has demonstrated extraordinary resilience under the tests of world wars, the Great Depression, stagflation, tech bubbles, and bank runs, this resilience is not coincidental. It is built on a rare and volatile combination of components that most countries cannot piece together, let alone maintain for decades.

First is global trade. For nearly a century, the U.S. has been the central node of the world's commercial network—not because it produces the cheapest goods, but because it offers the deepest markets, the most reliable currency, and the broadest consumer base. Trade has been the unsung hero of American prosperity, enabling the U.S. to import low-cost goods, export high-value services, and convert global surpluses into domestic assets.

Second is political stability. Regardless of how people evaluate the polarization and absurdities of the two-party system, the peaceful transfer of power every four years and the continuity of contracts, courts, and governance provide confidence for capital to stay. Investors may dislike regulation, but they dislike chaos even more.

Add to that a sound legal and regulatory framework. Property rights. Bankruptcy courts. Enforceable contracts. These are the dull, technical structures of capitalism, but without them, capital cannot flow.

Of course, there is also the dollar. The U.S. reserve currency status creates a gravitational field for global capital. Foreign central banks, sovereign wealth funds, multinational corporations: they all hold dollar reserves, settle transactions in dollars, and manage risks in dollars. This demand depresses U.S. borrowing costs and grants it an unparalleled ability to maintain deficits without immediate consequences.

Finally, there is luck. Two oceans, interwoven rivers and navigable waterways, natural harbors, favorable agricultural conditions, and a century and a half without hostile neighbors. Abundant natural resources. A population boom at critical times. A continental-scale internal market. If one were to design a country destined for dominance, the map of the U.S. would be the best blueprint. At the very least, it can be said that the U.S. is quite lucky.

This system appears solid on the surface, but it is actually intricate and interdependent—this balance is maintained by the inevitability of geopolitics, norms, incentives, and a polite collective illusion that tomorrow will be roughly the same as today. Only large-scale geopolitical events that significantly adjust the system's architecture will lead to long-term volatility, without moments of "buying the dip"—1971 is a classic example.

Returning to the fundamental question, this issue will soon find an answer.

What is the cost of unpredictability?

What is the cost of unpredictability? Honestly, I don't know. I think no one knows. But the limits of what this system can bear are finite, and once crossed, they cannot be reversed. Perhaps the good news is that the U.S. still wields more influence than any other country in the world. However, unless other countries unite or are willing to endure more pain than the Trump administration anticipates.

Related reading: Trump's Tariff Suspension: Analyzing Investment Opportunities in the 90-Day Window for the Crypto Market

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。