In the current process of continuous integration between virtual assets and the real economy, various RWA projects have different intentions and mechanisms, featuring both technological innovations and financial experiments.

Written by: Crypto Salad

Recently, discussions about RWA projects have been fervent in major Web3 communities. Industry observers often assert online that "RWA will reconstruct Hong Kong's new financial ecosystem," believing that relying on the existing regulatory framework of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, this sector will usher in breakthrough developments. During exchanges and discussions with many colleagues, Crypto Salad found that there has been ongoing debate about the so-called "compliance" issues, with varying understandings of "what compliance is," leading to a situation where each side has its own reasoning. This phenomenon arises from the existing differences in understanding the concept of RWA.

Therefore, it is necessary for Crypto Salad, from the perspective of a professional legal team, to discuss how the concept of RWA should be defined and to clarify the compliance red lines of RWA.

1. How should the concept of RWA be defined?

(1) Background and Advantages of RWA Projects

Currently, RWA is becoming the focus of market discussions and is gradually forming a new wave of development. This phenomenon is mainly based on the following two backgrounds:

First, the advantages of tokens can compensate for the shortcomings of traditional financing.

Projects in traditional financial markets have long faced high entry barriers, long financing cycles, slow financing speeds, and complex exit mechanisms. However, token financing can bypass these deficiencies. Compared to traditional IPOs, RWA has the following significant advantages:

1. Fast financing speed: Since token circulation is based on blockchain technology and typically occurs in decentralized intermediary trading institutions, it avoids obstacles such as foreign investment entry restrictions, industry policy constraints, and lock-up period requirements that traditional financial projects may encounter, while also compressing the review process that originally takes months or even years, greatly enhancing the financing speed.

2. Asset diversification: Traditional IPOs have a single type of asset, only supporting equity issuance, thus imposing strict requirements on the revenue stability, profitability, and asset-liability structure of the issuing entity. However, for RWA, suitable asset types are more diverse, encompassing various non-standard assets, which not only expands the range of financeable assets but also shifts the focus of credit assessment to the quality of underlying assets, significantly lowering the qualification threshold for issuing entities.

3. Relatively low financing costs: Traditional IPOs require long-term collaboration among multiple intermediary institutions such as investment banks, auditing firms, and law firms, with total costs for the listing process potentially reaching millions or even tens of millions. However, RWA issues tokens through decentralized exchanges, saving a significant amount of intermediary fees, while also reducing another large portion of labor costs through the operation of smart contracts.

In summary, RWA has taken the spotlight in financing projects due to its unique advantages, while the Web3 world and the cryptocurrency space particularly need funds and projects from the traditional real world. This has led to a situation where, whether aiming for substantial business transformation or simply wanting to "ride the wave" and gain attention, leading projects in segmented fields of listed companies and various "quirky" startups are actively exploring the application possibilities of RWA.

Second, Hong Kong's "compliance" has added fuel to the fire.

In fact, RWA has been developing overseas for some time, and this wave of enthusiasm has surged because Hong Kong has passed a series of regulatory innovations and launched several benchmark projects, providing domestic investors with a compliant channel to participate in "RWA" for the first time. The "compliant" RWA accessible to the Chinese public has been realized. This groundbreaking progress has not only attracted native crypto assets but has also prompted traditional projects and funds to begin paying attention to the investment value of RWA, ultimately driving market enthusiasm to new heights.

However, do users eager to try RWA really understand what RWA is? With a plethora of RWA projects, do people recognize the differences in their underlying assets and operational structures? Therefore, we believe it is necessary to define what constitutes compliant RWA through this article.

People generally believe that RWA refers to financing projects that tokenize underlying real-world assets through blockchain technology. However, when we scrutinize the underlying assets of each project and trace back the operational processes, we find that the underlying logic of these projects actually differs. We conducted systematic research on this issue and summarized the following understanding of the concept of RWA:

We believe that RWA is actually a broad concept without a so-called "standard answer." The process of asset tokenization through blockchain technology can all be referred to as RWA.

(2) Elements and Characteristics of RWA Projects

True RWA projects need to possess the following characteristics:

1. Based on real assets

Whether the underlying assets are real and whether the project can establish a transparent and acceptable third-party audit mechanism for off-chain asset verification is a key criterion for determining whether the project's tokens will achieve effective value recognition in reality. For example, PAXG issues tokens that are anchored to gold in real-time, with each token backed by 1 ounce of physical gold, and the gold reserves are managed by a third-party platform, audited quarterly by a third-party auditing firm, and even support redeeming the corresponding amount of physical gold with tokens. This high level of transparency and regulated asset verification mechanism allows the project to gain investor trust and provides a basis for effective valuation in the real financial system.

2. Asset tokens on-chain

Asset tokenization refers to the process of converting real-world assets into digital tokens that can be issued, traded, and managed on-chain through smart contracts and blockchain technology. The value transfer and asset management processes of RWA are executed automatically through smart contracts. Unlike traditional financial systems that rely on intermediary institutions for transactions and settlements, RWA projects can leverage smart contracts to achieve transparent, efficient, and programmable business logic execution on the blockchain, significantly enhancing asset management efficiency and reducing operational risks.

Asset tokenization endows RWA with key characteristics of being divisible, tradable, and highly liquid. After asset tokenization, assets can be split into smaller tokens, lowering the investment threshold and changing the way assets are held and circulated, allowing retail investors to participate in investment markets that were previously high-threshold.

3. Digital assets have ownership value

The tokens issued by RWA projects should belong to digital assets with property attributes. The project should clearly distinguish between data assets and digital assets: data assets are collections of data owned by enterprises that can create value. In contrast, digital assets are the value itself and do not require re-pricing through data. For example, when you design a painting, upload it to the blockchain, and generate an NFT, this NFT is a digital asset because it can be verified and traded. However, the large amount of feedback, browsing data, and click data you collect from users regarding the painting belongs to data assets; you can analyze the data assets to gauge user preferences, improve your work, and adjust its price.

4. The issuance and circulation of RWA tokens comply with legal regulations and are subject to administrative supervision

The issuance and circulation of RWA tokens must operate within the existing legal framework; otherwise, it may not only lead to project failure but also trigger legal risks. First, real-world assets must be genuine and legal, with clear and undisputed ownership, so they can serve as the basis for token issuance. Second, RWA tokens typically possess rights to income or asset interests, making them easily classified as securities by regulatory authorities in various countries, thus requiring compliance with local securities regulations before issuance. The issuing entity must also be a qualified institution, such as one holding an asset management or trust license, and must complete KYC and anti-money laundering procedures. Once in circulation, the trading platform for RWA tokens must also be regulated, usually requiring compliance with trading exchanges or secondary markets with financial licenses, and trading on decentralized platforms is not allowed. Additionally, continuous information disclosure is required to ensure that investors can access the true situation of the assets linked to the tokens. Only under such a regulatory framework can RWA tokens be legally and safely issued and circulated.

Moreover, the compliance management of RWA has typical cross-jurisdictional characteristics, so it is essential to build a systematic compliance framework covering the legal norms of the asset's location, the flow of funds, and various regulatory authorities. Throughout the entire lifecycle of asset on-chain, cross-chain, and token cross-border and cross-platform circulation, RWA must establish a compliance mechanism covering multiple aspects such as asset verification, token issuance, fund flow, income distribution, user identification, and compliance auditing. This not only involves legal consulting and compliance design but may also require the introduction of third-party trust, custody, auditing, and regulatory technology solutions.

(3) Types and Regulation of RWA Projects

We have found that there are two parallel types of RWA projects that meet the requirements:

1. Narrowly defined RWA: Physical assets on-chain

We believe that narrowly defined RWA specifically refers to projects that tokenize real assets that are authentic and verifiable on-chain, which is also the common understanding of RWA among the public, and its application market is the most extensive, such as projects that anchor tokens to real-world assets like real estate and gold.

2. STO (Security Token Offering): Financial assets on-chain

In addition to narrowly defined RWA projects, we have found that many existing RWA projects in the market are actually STOs.

(1) Definition of STO

Based on the underlying assets, operational logic, and token functions, existing tokens in the market can generally be divided into two categories: utility tokens and security tokens. STO refers to the process of financializing real assets and issuing tokenized shares or certificates in the form of security tokens on the blockchain.

(2) Definition of security tokens

Security tokens, in contrast to utility tokens, are simply defined as on-chain financial products driven by blockchain technology that are subject to securities regulations, similar to electronic stocks.

(3) Regulation of security tokens

Under the regulatory frameworks of major crypto-friendly countries like the United States and Singapore, once a token is classified as a security token, it will be subject to the constraints of traditional financial regulatory bodies (such as securities regulatory commissions), and the token design, trading models, etc., must comply with local securities regulations.

From an economic perspective, the core goal of financial products is to coordinate the supply and demand relationship between financing parties and investors; from a legal regulatory perspective, some countries focus more on protecting investor interests, while others lean towards encouraging smooth financing activities and innovation. This difference in regulatory stance is reflected in the specific rules, compliance requirements, and enforcement intensity within each country's legal system. Therefore, when designing and issuing RWA products, it is essential to consider not only the authenticity and legality of the underlying assets but also to conduct a comprehensive review and compliance design of key aspects such as product structure, issuance methods, circulation paths, trading platforms, investor access thresholds, and funding costs.

It is particularly noteworthy that if the core appeal of a certain RWA project comes from its high leverage and high return expectations, and it uses "hundredfold, thousandfold returns" as a primary selling point, then regardless of its superficial packaging, its essence is very likely to be classified as a securities product by regulatory authorities. Once classified as a security, the project will face a more stringent and complex regulatory system, significantly increasing its subsequent development path, operational costs, and legal risks.

Therefore, when discussing the legal compliance of RWA, we need to deeply understand the connotation of "securities regulations" and the regulatory logic behind it. Different countries and regions have varying definitions and regulatory focuses regarding securities. The United States, Singapore, and Hong Kong have all defined the criteria for identifying security tokens. It is not difficult to see that the defining method essentially judges whether the token meets the local securities regulations' criteria for "securities." Once the conditions for securities are met, it is classified as a security token. Therefore, we have organized the relevant provisions from key countries (regions) as follows:

A. Mainland China

In the regulatory framework of Mainland China, the "Securities Law of the People's Republic of China" defines securities as stocks, corporate bonds, depository receipts, and other negotiable instruments recognized by the State Council, and also includes the listing and trading of government bonds and securities investment fund shares under the regulation of the "Securities Law."

(The above image is taken from the "Securities Law of the People's Republic of China")

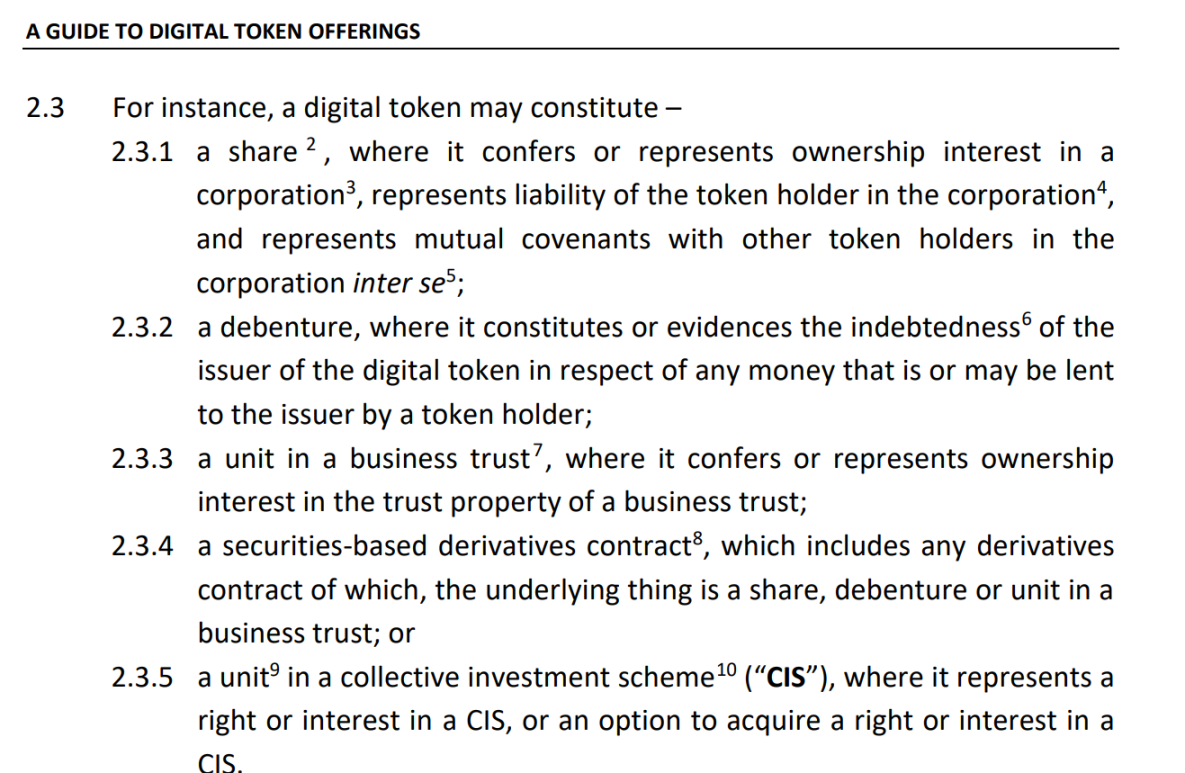

B. Singapore

Although Singapore's "Guidelines on Digital Token Offerings" and the "Securities and Futures Act" do not directly mention the concept of "security tokens," they detail various circumstances under which tokens may be recognized as "capital market products":

(The above image is taken from the "Guidelines on Digital Token Offerings")

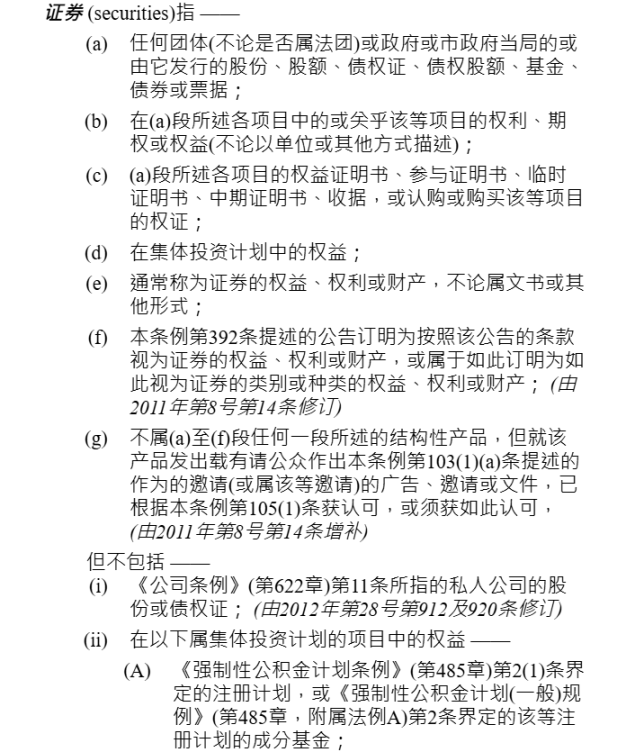

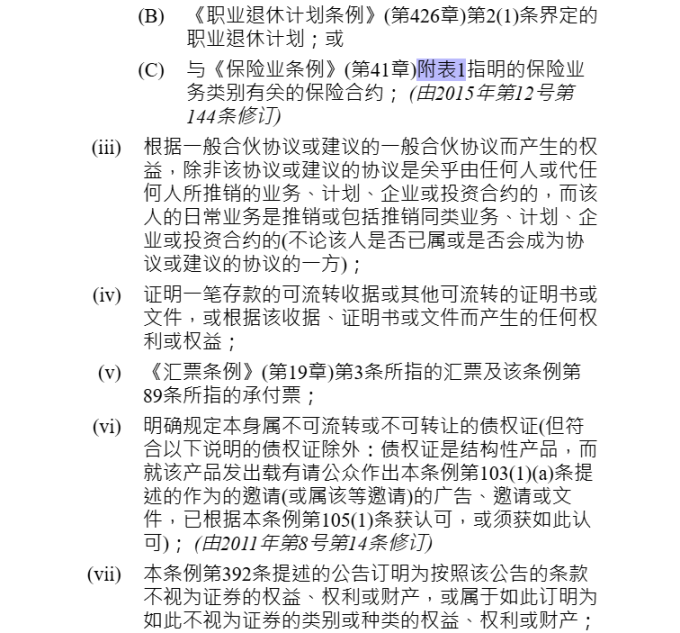

C. Hong Kong

The Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) of Hong Kong has specific enumerative provisions regarding the positive and negative lists of securities in the "Securities and Futures Ordinance":

(The above images are taken from the "Securities and Futures Ordinance")

The ordinance defines "securities" to include "shares, equity shares, notes, bonds," and structured products, without limiting their existence to traditional carriers. The SFC has explicitly pointed out in the "Circular on Intermediaries Engaging in Tokenized Securities Activities" that the nature of its regulatory targets is essentially traditional securities packaged as tokens.

D. United States

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) stipulates that any product passing the Howey Test is classified as a security. Any product identified as a security must be regulated by the SEC. The Howey Test is a legal standard established by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1946 SEC v. W.J. Howey Co. case, used to determine whether a transaction or scheme constitutes an "investment contract," thus subjecting it to U.S. securities law regulation.

The Howey Test outlines four conditions for a financial product to be recognized as a "security." The SEC's "Framework for 'Investment Contract' Analysis of Digital Assets" specifies the application of the Howey Test to digital assets. We will analyze this in detail next:

The Investment of Money

This refers to the investment of money or assets by investors to obtain certain rights or expected returns. In the digital asset field, whether using fiat currency or cryptocurrency to purchase tokens, as long as there is a value exchange, it generally meets this standard. Therefore, most token issuances essentially comply with this condition.

Common Enterprise

"Common enterprise" refers to a close binding of interests between investors and the issuer, typically manifested as the investors' returns being directly related to the project's operational effectiveness. In token projects, if the returns for token holders depend on the issuer's business development or platform operational results, it meets the characteristics of a "common enterprise," and this condition is also relatively easy to establish in practice.

Reasonable Expectation of Profits Derived from Efforts of Others

This is the key point in determining whether a token will be classified as a security token. This condition means that if the purpose of the investor purchasing the product is to expect future appreciation of the product or to obtain other economic returns, and such returns do not come from their own use or operational activities but rely on the overall development of the project created by others' efforts, then the product may be considered a "security."

Specifically, in RWA projects, if the investor's purpose in purchasing tokens is to obtain future appreciation or economic returns, rather than returns from their own use or operational activities, then the token may have "profit expectations," thus triggering the determination of its securities attributes. Especially when the token's returns heavily depend on the professional operations of the issuer or project team, such as liquidity design, ecosystem expansion, community building, or cooperation with other platforms, this characteristic of "relying on others' efforts" further enhances its potential for securitization.

RWA tokens that genuinely possess sustainable value should be directly anchored to the real returns generated by underlying real assets, rather than relying on market speculation, narrative packaging, or platform premiums to drive their value growth. If the value fluctuations of the tokens primarily stem from the "recreation" of the underlying team or platform operations rather than the income changes of the assets themselves, then it does not possess the characteristics of "narrowly defined RWA" and is more likely to be viewed as a security token.

The introduction of the Howey Test by the SEC in regulating crypto tokens means that it no longer relies on the form of the token to determine its regulatory stance but shifts to substantive review: focusing on the actual functions, issuance methods, and investor expectations of the tokens. This change marks a trend towards stricter and more mature legal positioning of crypto assets by U.S. regulatory agencies.

2. What is the legal logic behind the "compliance" layering of RWA projects?

Having discussed the concepts and definitions of RWA, we now return to the core question raised at the beginning of the article, which is a focal point of industry concern:

To date, which types of RWA can be considered truly "compliant" RWA? How can we meet the compliance requirements of RWA projects in practice?

First, we believe that compliance means being regulated by local regulatory authorities and conforming to the provisions of the regulatory framework. In our understanding, the compliance of RWA is a layered system.

First Layer: Sandbox Compliance

This specifically refers to the Ensemble sandbox project designed by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), which is currently the narrowest and most regulatory pilot definition of "compliance." The Ensemble sandbox encourages financial institutions and technology companies to explore technological and model innovations in tokenization applications through projects like RWA in a controlled environment to support its leading digital Hong Kong dollar project.

The HKMA has shown a high level of concern for the sovereignty of future monetary systems in promoting the central bank's digital Hong Kong dollar (e-HKD) and exploring the regulation of stablecoins. The competition between central bank digital currencies and stablecoins is essentially a redefinition and contestation of "monetary sovereignty." The sandbox provides project parties with policy space and flexibility to some extent, facilitating exploratory practices for on-chain real assets.

At the same time, the HKMA is actively guiding the development of tokenized assets, attempting to expand their applications in real scenarios such as payments, settlements, and financing within a compliance framework. Several technology and financial institutions, including Ant Group, are members of the sandbox community, participating in the construction of the digital asset ecosystem. Projects entering the regulatory sandbox signify a higher level of compliance and policy recognition to some extent.

However, from the current situation, such projects are still in a closed operational state and have not yet entered the broader secondary market circulation stage, indicating that there are still practical challenges in asset liquidity and market connectivity. Without a stable funding supply mechanism and efficient secondary market support, the entire RWA token system is unlikely to form a true economic closed loop.

Second Layer: Hong Kong Administrative Regulatory Compliance

As an international financial center, Hong Kong has been continuously promoting institutional exploration in the virtual asset field in recent years. As the first region in China to explicitly promote virtual assets, especially the development of tokenized securities, Hong Kong has become a target market for many mainland project parties due to its open, compliant, and clearly defined regulatory environment.

By reviewing the relevant circulars and policy practices issued by the Hong Kong SFC, it is not difficult to find that the core of Hong Kong's regulation of RWA is to incorporate it into the STO framework for compliance management. Moreover, the SFC has established a relatively complete licensing system for virtual asset service providers (VASP) and virtual asset trading platforms (VATP) and is preparing to release a second virtual asset policy declaration to further clarify the regulatory attitude and basic principles when virtual assets are combined with real assets. Under this institutional framework, tokenization projects involving real assets, especially RWA, have been included in a higher level of compliance regulatory category.

From the perspective of RWA projects that have already been implemented in Hong Kong and have a certain market influence, most projects possess clear securities attributes. This means that the tokens they issue involve ownership, income rights, or other transferable rights related to real assets, which can constitute "securities" as defined under the "Securities and Futures Ordinance." Therefore, such projects must be issued and circulated in the form of security tokens (STO) to obtain regulatory approval and achieve compliant market participation.

In summary, Hong Kong's regulatory positioning for RWA has become relatively clear: any mapping of real assets with securities attributes on-chain should be included in the STO regulatory system. Therefore, we believe that the RWA development path currently promoted by Hong Kong is essentially a specific application and practice of the security tokenization (STO) path.

Third Layer: Clear Regulatory Framework in Crypto-Friendly Regions

In some regions with an open attitude towards virtual assets and relatively mature regulatory mechanisms, such as the United States, Singapore, and some European countries, a more systematic compliance path has been established for the issuance, trading, and custody of crypto assets and their mapping of real assets. RWA projects in such regions can be considered compliant RWA operating under a clear regulatory system if they obtain the necessary licenses, comply with information disclosure, and meet asset compliance requirements.

Fourth Layer: "Pan-Compliance"

This is the broadest sense of compliance, in contrast to "non-compliance," specifically referring to RWA projects in certain offshore jurisdictions where the government temporarily adopts a "laissez-faire" attitude towards the virtual asset market, without being explicitly identified as illegal or non-compliant, and where their business models have a certain compliance space within the local legal framework. Although the scope and concept of this compliance are relatively vague and do not constitute complete legal confirmation, it falls under the business status of "what is not prohibited by law can be done" before legal regulation becomes clear.

In reality, we can observe that the vast majority of RWA projects find it difficult to achieve the first two types of compliance. Most projects choose to attempt the first three paths—relying on the lenient policies of certain crypto "friendly" jurisdictions to try to bypass sovereign regulatory boundaries and achieve formal "compliance" at a lower cost.

As a result, RWA projects appear to be "popping up like dumplings," but the time for generating substantial financial value has not yet arrived. The fundamental turning point will depend on whether Hong Kong can clearly explore the secondary market mechanisms for RWA—especially how to open up cross-border capital circulation channels. If RWA trading remains confined to a closed market aimed at local retail investors in Hong Kong, both asset liquidity and capital scale will be extremely limited. To achieve breakthroughs, it must allow global investors to invest in Chinese-related assets through compliance mechanisms, indirectly "buying the dip" in China in the form of RWA.

Hong Kong's role here can be likened to the significance of Nasdaq for global tech stocks in the past. Once the regulatory mechanism matures and the market structure becomes clear, when Chinese individuals want to "go abroad" for financing and foreigners want to "buy the dip" in Chinese assets, the first stop will undoubtedly be Hong Kong. This will not only be a regional policy dividend but also a new starting point for the reconstruction of financial infrastructure and capital market logic.

In summary, we believe that compliance for RWA projects should be pursued within the current framework, and all projects must maintain policy sensitivity. Once there are legal adjustments, urgent changes must be made. Given that current regulations are not yet fully clarified and the RWA ecosystem is still in the exploratory stage, we strongly recommend that all project parties actively engage in "self-compliance" efforts. Although this means investing more resources and bearing higher time and compliance costs in the early stages of the project, in the long run, it will significantly reduce systemic risks in areas such as legal, operational, and investor relations.

Among all potential risks, fundraising risk is undoubtedly the most lethal hidden danger for RWA. Once a project design is deemed illegal fundraising, regardless of whether the assets are real or the technology is advanced, it will face significant legal consequences, posing a direct threat to the project's survival and delivering a heavy blow to the company's assets and reputation. In the development of RWA, there will inevitably be differences in compliance definitions across different regions and regulatory environments. Developers and institutions must combine their business types, asset attributes, and regulatory policies of target markets to formulate detailed phased compliance strategies. Only by ensuring that risks are controllable can RWA projects be steadily advanced.

### Legal Advice for RWA Projects

As a summary, we, as a legal team, systematically outline the core aspects that RWA projects need to pay attention to during the full-chain advancement process from a compliance perspective.

1. Choose Policy-Friendly Jurisdictions

In the current global regulatory landscape, the compliance advancement of RWA projects should prioritize jurisdictions with clear policies, mature regulatory systems, and an open attitude towards virtual assets, which can effectively reduce compliance uncertainty.

2. Underlying Assets Must Have Real Payability

Regardless of how complex the technical architecture is, the essence of RWA projects is still to map the rights of real assets onto the blockchain. Therefore, the authenticity of the underlying assets, the reasonableness of their valuation, and the executability of the payment mechanism are all core factors determining the project's credibility and market acceptance.

3. Obtain Investor Recognition

The core of RWA lies in asset mapping and rights confirmation. Therefore, whether the final buyers or users of the off-chain assets recognize the rights represented by the on-chain tokens is key to the project's success or failure. This not only involves the personal willingness of investors but is also closely related to the legal attributes of the tokens and the clarity of rights.

While promoting the compliance process, RWA project parties must also face another core issue: investors must be informed. In reality, many projects package risks in complex structures and do not clearly disclose the status of underlying assets or the logic of token models, leading investors to participate without a full understanding. Once fluctuations or risk events occur, it not only triggers a market trust crisis but may also attract regulatory attention, making the situation even more difficult to handle.

Therefore, establishing a clear investor screening and education mechanism is crucial. RWA projects should not be open to all groups but should consciously introduce mature investors with a certain risk tolerance and financial understanding. In the early stages of the project, it is especially necessary to set certain thresholds, such as professional investor certification mechanisms, participation limits, and risk disclosure briefings, to ensure that entrants are "informed and voluntary," truly understanding the asset logic, compliance boundaries, and market liquidity risks behind the project.

4. Ensure Institutional Operators in the Chain Comply with Regulations

In the full process of RWA, it often involves multiple aspects such as fundraising, custody, valuation, tax processing, and cross-border compliance. Each aspect corresponds to regulatory agencies and compliance requirements in reality. Project parties need to complete compliance declarations and regulatory connections within the relevant legal framework to reduce legal risks. For example, in parts involving fundraising, special attention should be paid to whether it triggers compliance obligations related to securities issuance, anti-money laundering, etc.

5. Prevent Post-Compliance Risks

Compliance is not a one-time action; after the RWA project is implemented, it must continue to face changes in the dynamic regulatory environment. How to prevent potential administrative investigations or compliance accountability in the post-implementation phase is an important guarantee for the project's sustainable development. It is recommended that project parties establish a professional compliance team and maintain a communication mechanism with regulatory agencies.

6. Brand Reputation Management

In the highly sensitive information dissemination environment of the virtual asset industry, RWA projects must also pay attention to public opinion management and market communication strategies. Building a transparent, trustworthy, and professional project image helps enhance public and regulatory trust, creating a favorable external environment for long-term development.

### Conclusion

In the current process of continuous integration of virtual assets and the real economy, various RWA projects have different intentions and mechanisms, involving both technological innovation and financial experimentation. The capabilities, professionalism, and practical paths of different projects vary widely, warranting our individual study and classification observation.

Through extensive research and project participation, we have also deeply realized that for market participants, the biggest challenge often lies not in the technical aspect but in the uncertainty of the system, especially the unstable factors in administrative and judicial practices. Therefore, what we need more is to explore "practical standards"—even if we do not have legislative and regulatory authority, promoting the formation of industry standardization and compliance in practice is still valuable. As long as there are more participants, mature paths, and regulatory agencies establish sufficient management experience, the system will gradually improve. Within the framework of the rule of law, fostering cognitive consensus through practice and promoting institutional evolution through consensus is a form of "bottom-up" positive institutional evolution for society.

However, we must also keep compliance warnings ringing. Respecting existing judicial and regulatory frameworks is the basic premise for all innovative actions. Regardless of how the industry develops or how technology evolves, the law remains the bottom-line logic that safeguards market order and public interest.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute legal advice or opinions on specific matters.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。