The Game Between State and Market: A Contest of Credit and the Scepter of Institutions

Written by: Liu Honglin

The Summer of the Salt Lake

In the summer of the 42nd year of Qianlong, the surface of the salt lake in Yuncheng had lost its previous azure hue, revealing layers of glaring salt crust, as if the earth was shedding its old skin under the scorching sun.

Cao Dehai stood at the entrance of the salt field, watching the workers carry basket after basket of salt into storage, but his heart felt as parched as the lake itself. Tomorrow was the day the Salt Transport Office would come to collect the salt tax. Without that half-foot-long salt ticket, no matter how much salt he had, it was merely contraband, unable to pass the checkpoints and leave Yuncheng.

In the world of the salt lake, the salt ticket is a passport, a key to wealth, and a shackle from the government. The salt ticket is made of jute paper, stamped with the red official seal of the "Salt Transport Office of Hedong," with the merchant's name, ticket number, and tax amount written on the back. It appears light, yet it is the lifeline of the salt merchants for an entire year.

Historical records state that the Yuncheng salt lake produces nearly five million dan of salt annually, accounting for about one-tenth of the national total. The salt tax from Hedong contributes to thirty percent of Shanxi Province's finances (Compilation of Historical Materials on Salt Administration in the Qing Dynasty, Volume 5). The salt from the salt lake is not just a seasoning on the common people's tables; it is also the military pay for the government and the lifeblood of the dynasty.

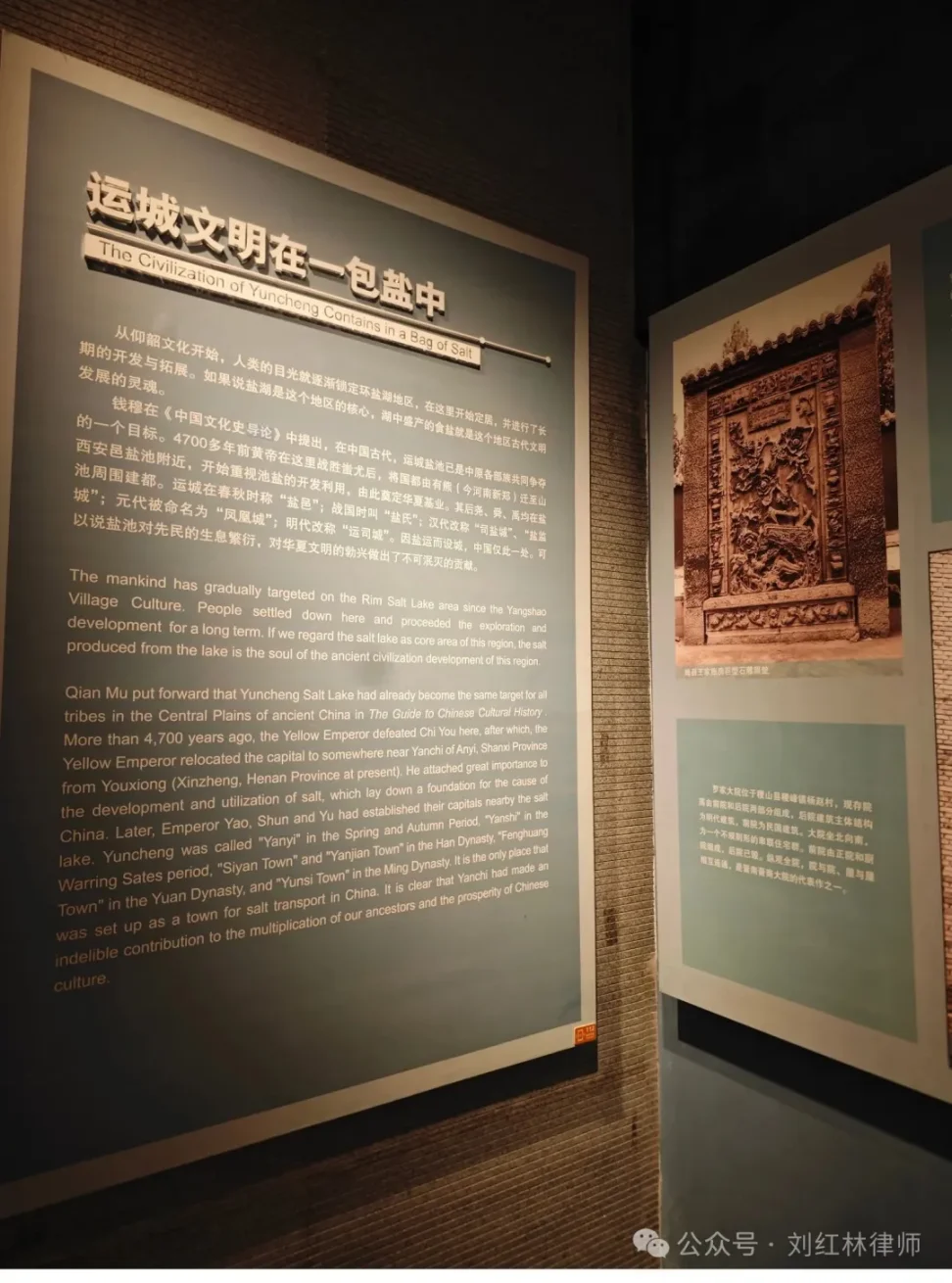

Qian Mu wrote in "An Introduction to Chinese Cultural History": "The Yuncheng salt lake has become a target for various tribes in the Central Plains to compete for." Over 4,700 years ago, after the Yellow Emperor defeated Chiyou, he moved the capital near the Anyi salt lake, initiating the development and utilization of lake salt, laying the first stake for the foundation of Huaxia. Subsequently, Yao, Shun, and Yu established their capitals here. During the Spring and Autumn period, it was called "Salt City," in the Warring States period "Salt Clan," in the Han Dynasty "Salt Supervision City," in the Yuan Dynasty "Phoenix City," and in the Ming Dynasty "Transport City." This is the only place in China established for salt transport.

Cao Dehai remembered his father saying before he passed away: "What we are doing is not a salt business, but a salt ticket business. Without the salt ticket, no matter how much salt you carry, you are just carrying a knife."

The Downstream of Salt Merchants

The establishment of the salt ticket can be traced back to the "Kaizhong Law" during the Hongwu period of the Ming Dynasty. Since then, the state has held the wealth of the salt lake in its hands with a piece of salt ticket.

The salt ticket serves as a certificate of circulation, a receipt for the court's salt tax, and the lifeblood of the national finances. However, during the Qianlong period, with the rise of ticket houses and the prosperity of postal routes, the nature of the salt ticket quietly changed: it was no longer just a certificate for exchanging salt but also became an object for merchants to resell.

Salt merchants learned a new business: obtaining salt tickets, not rushing to exchange for salt, but selling them to others for a profit. The tickets were traded back and forth in teahouses and taverns, becoming a type of "financial instrument" that wandered in the gray area.

The "Compilation of Historical Materials on Salt Administration in the Qing Dynasty" records: "The trend of ticket merchants reselling has deepened, to the point where silver tickets and salt tickets are exchanged, and the government tax is often lost." The salt ticket, originally a tool for the government to control the salt lake, grew branches in the gaps of the market. In the 37th year of Qianlong, a major case of reselling erupted in the Yuncheng salt lake, involving even officials from the Salt Transport Office. The memorial stated: "In the case of reselling, dozens of officials were implicated, hundreds of merchants were involved, the salt tax was interrupted, and the treasury was in deficit." (Compilation of Qing Dynasty Salt Administration Archives, Volume 32)

But the government's calculations never ceased.

Reselling disrupted the market but also became a lubricant for finances. The "service fees" from reselling transactions and the profits for officials became a hidden source of local salt tax revenue. The Hedong Salt Transport Commissioner wrote in a memorial in the 42nd year of Qianlong: "Although reselling is a malady, the tax can still be collected; strict prohibition may lead to interruptions, and we are especially concerned that the use of salt tickets may not continue."

Thus, the state and the market repeatedly tested each other under the red stamp of the salt ticket. The state relied on salt tickets to maintain military pay and the bureaucracy; salt merchants used reselling and ticket pooling to convert red tickets into silver. The credit of the salt ticket ultimately depended on the authority of the government and the intimidation of salt police; while the power of the market could always navigate through the gaps of authority.

Those porters and ticket houses caught in the crevices of the salt tickets perhaps understood this principle best: in this world, there is no pure freedom, nor absolute prohibition.

The Co-opted Cryptocurrency

Some say that cryptocurrency is decentralized and represents the ultimate challenge to the state's right to issue currency. The consensus of algorithms, distributed ledgers, and anonymous wallets seem to allow wealth to break free from the shackles of the state for the first time, flowing freely like the winds of the salt lake.

However, the history of the salt lake has long written the answer. Reselling was originally a disease that disrupted the monopoly, yet it became a lubricant on the government's ledger; the red stamp of the salt ticket is both a prohibition and a permission. Behind the ideal of decentralization, there are always the tentacles and shadows of the state.

People thought cryptocurrency was the ultimate challenge to the state's right to issue currency, but as the industry has evolved, embracing regulation has become the main theme. KYC, AML, exchange compliance, tax transparency—these terms layer upon "decentralization" like frost on salt in the wind.

The state's calculations can always incorporate the ideal of freedom into the framework of the system.

In 2025, at the Bitcoin conference, U.S. Vice President Vance candidly stated: "Bitcoin is a tool to combat bad policies, regardless of which party's policies. The Chinese government does not like Bitcoin… Since China is distancing itself from Bitcoin, perhaps we in America should move towards Bitcoin. We have established a national Bitcoin reserve, making Bitcoin a strategic tool for the U.S. government. Stablecoins pegged to the dollar will not weaken the dollar; rather, they will amplify the strength of the U.S. economy."

Just as the salt ticket controlled the circulation of salt in the salt lake, today's regulatory agencies use compliance licenses and on-chain monitoring to grasp the flow of wealth at their digital fingertips. The state may have lost its monopoly on paper tickets, but it has rebuilt an invisible wall with laws, licenses, and on-chain monitoring. The regulatory hand reaches into every wallet address, and the public transparency of on-chain data has instead become a new weapon for the state.

The state's hand has never truly loosened its grip on the reins of wealth.

The Game of Power

The story of the salt lake has faded, and the salt ticket has become a yellowed page in history books. Yet, the yellowed jute paper still bears the traces of the collusion between the state and the market. The circulation of wealth has never been a simple exchange of goods; it is a game between the state and the market, a contest of credit, and the scepter of institutions.

The credit of the salt ticket ultimately rests on the authority of the government; the credit of cryptocurrency appears decentralized but also lingers under the shadow of state law. Without regulatory permission and tax pathways, no matter how many nodes cryptocurrency has, it can only wander in the gray and white.

Standing by the Yuncheng salt lake, looking at the layers of dried salt frost, I seem to see the underlying color of wealth: half is the desire of the market, and half is the shackle of the system. The forms of salt tickets, paper money, and Bitcoin have changed, but the essence of power remains unchanged.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。