Author: Xiao Xiaopao

Over the years, while focusing on my main business, I've also been casually writing articles and doing podcasts. Although I haven't made a dime, this activity has brought me a convenience:

Whenever you see a hot topic starting to spin wildly, and the GPUs are burning out, all you have to do is search through the articles you've written, the questions you've pondered, and the podcasts you've made—I bet a Labubu that there's a 90% chance you'll find relevant content—there's nothing new under the sun; you've actually thought about these things long ago and already have some ideas and connections (of course, the premise is that you've been casually exploring for at least a complete cycle of 5-8 years).

For example, the recent resurgence of stablecoins. As an old hand, I can confidently say that I've seen this game before. But it always re-emerges with new terms and new looks. To be fair, it is indeed different from before; you can't say it hasn't progressed at all. However, as soon as you change a term, all the concepts along the entire value chain will don new clothes, and the cost of re-understanding it will inevitably increase. You will have to spend some tokens to discover that 80%-90% of the content is something you've already thought about.

Today, I want to talk about Erebor Bank.

Yesterday, Teacher Will threw out an article, excitedly wanting to record a follow-up on stablecoins—the reason being "Peter Thiel is getting into banking again—stablecoin banking."

My accommodating personality got excited for 5 minutes and eagerly agreed. Then I entered a state of emptiness: that's right, it's that familiar feeling of "I've seen this plot somewhere before"—this person, widely regarded as influencing the current U.S. government, the "deep state," Silicon Valley's godfather, who last advised everyone to withdraw from Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), directly leading to its bank run and collapse, is Peter Thiel, and he's getting into banking again?

This time, he and Palmer Luckey, co-founder of Anduril (a defense technology company), are set to create a new crypto bank named "Erebor."

First, let's shake off that old hand feeling. No investigation, no right to speak; let's gather some information first.

01 | The Fable of Erebor

To be fair, the name is quite interesting. As a fan of The Lord of the Rings, I have a good impression right off the bat.

Erebor, the "Lonely Mountain" in The Lord of the Rings, is where Smaug sleeps. Smaug is an evil dragon that lives by stealing gold and jewels from dwarves, elves, and humans, then burning everyone alive. He resides in a massive cave filled with gold and jewels, where he sleeps.

Hmm, this IP image seems a bit off, giving a sense of "the dragon-slaying youth eventually becomes the evil dragon"; but let's not dwell on that, perhaps this brand image aligns well with the tastes of the core customers of a crypto bank. Anyway, the naming conventions in Silicon Valley are either Greek mythology, Middle-earth, or Latin words read backward. At least Erebor has some literary taste.

Putting the name aside, what’s truly worth pondering is: why is Silicon Valley opening a new bank at a time when stablecoins are (once again) hot?

02 | The Fall of SVB: 48 Hours

Almost all media reports mention: "to fill the huge gap left by the collapse of SVB" + "to support the wave of stablecoins."

Since SVB has been mentioned, let me help everyone review:

In March 2023, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) set a record in financial history: it went from "Forbes' Best Bank of the Year" to a "regulatory takeover" failure case in just 48 hours. At that time, I recorded two podcast episodes to join the fray (one from the perspective of an old hand, and one from the perspective of an old-timer), characterizing it as a "storm in a teacup"—SVB, as the 16th largest bank in the U.S. at the time, was far smaller than Lehman Brothers during the subprime crisis and did not shake the global financial market, but it was indeed a deep wound for the tech circle.

The trigger for the incident wasn't particularly explosive: on March 9, SVB announced the sale of $21 billion in securities, incurring an $1.8 billion loss, while needing to raise $2.25 billion to avoid a liquidity crisis. Once the news broke, a bank run occurred the next day, with depositors attempting to withdraw $42 billion, and the stock price plummeted over 60%. SVB's held-to-maturity securities incurred a market value loss of $15.9 billion, while its tangible common equity was only $11.5 billion. The result was that the government backed all depositors, but shareholders and bondholders lost everything, management was all fired, and the stock price went from over $200 to zero. This bank, which had been established for 40 years and had just issued year-end bonuses a few days prior, collapsed in an instant.

The fall of SVB exposed the fundamental mismatch between "traditional banking" and "innovative economy." SVB served over half of Silicon Valley's startups, but its business model was essentially from the 19th century—collecting deposits with one hand and issuing loans with the other, profiting from the interest spread.

The problem is that tech companies had just received truckloads of cash from VCs and had no need for loans; SVB could only invest these funds in long-term bonds, ultimately succumbing to duration mismatch and interest rate risk.

Of course, any bank could face this possibility. Duration mismatch is a core business model of commercial banks—there's always a risk of a bank run. The fall of SVB was an event that required the right timing, location, and people to mess up: (1) an extremely unique and singular customer structure; (2) extremely poor asset-liability management; (3) and precisely stepping on the cyclical reversal point of a 40-year low-interest-rate era.

First, let's discuss (1):

SVB's customer base was uniquely specialized. If you attended any VC meetings or startup events in the U.S. in recent years, you would have seen SVB setting up shop at the entrance—its customer base consisted solely of startups that had just secured funding, with no need for segmentation.

Now, let's look at (2):

During the Federal Reserve's quantitative easing from 2020 to 2021, financing for tech companies peaked, and SVB's deposits surged from $61 billion in 2019 to $189 billion in 2021, tripling in three years. With interest rates extremely low, these deposits were almost free capital.

The problem lay in the deposit structure: demand deposits and transaction accounts accounted for $132.8 billion, while savings and time deposits were only $6.7 billion, with demand deposits making up a staggering 76.72%. This was an extremely poor liability structure—corporate demand deposits are the most unstable, and SVB's corporate clients were all tech companies, completely lacking diversification and highly homogeneous.

With the liability side already dangerous, the asset side was even more distorted: don't forget that these clients only deposited money and did not take loans. Startups have no fixed assets and no stable cash flow, so banks couldn't lend. Thus, they bought a lot of bonds, initially short-term government bonds, but later, to increase yields, they shifted to long-term government bonds and (yes) agency mortgage-backed securities (various ABS).

In this way, the main risk of a bank shifted from credit risk to interest rate risk.

Then came (3): interest rates rose.

Under normal circumstances, rising interest rates are beneficial for banks—while deposit rates rise, loan rates also rise, and the interest spread remains basically unchanged or even increases. But SVB had a large amount of long-term bonds on its asset side (56% of assets, while the average for U.S. banks is only 28%), and when interest rates rose, the market value of those bonds fell.

Thus, a double whammy: asset-side bond devaluation, liability-side high interest rates, and a decrease in the supply of cheap deposits (does this plot sound familiar? There are similar cases domestically, called small and medium-sized banks).

Finally, add a spoonful of hot oil: all the tech companies in Silicon Valley are in the same WhatsApp group, and when Peter Thiel's Founders Fund led the withdrawal, the stampede happened in the blink of an eye—there's no creature on Earth more conformist than VCs, after all, FOMO and FUD are the cultural genes of this circle.

03 | Fall Down, Get Back Up

It doesn't matter that it collapsed. The wind will rise again, this time landing on the stablecoin hill. The same team decided to solve the problem themselves.

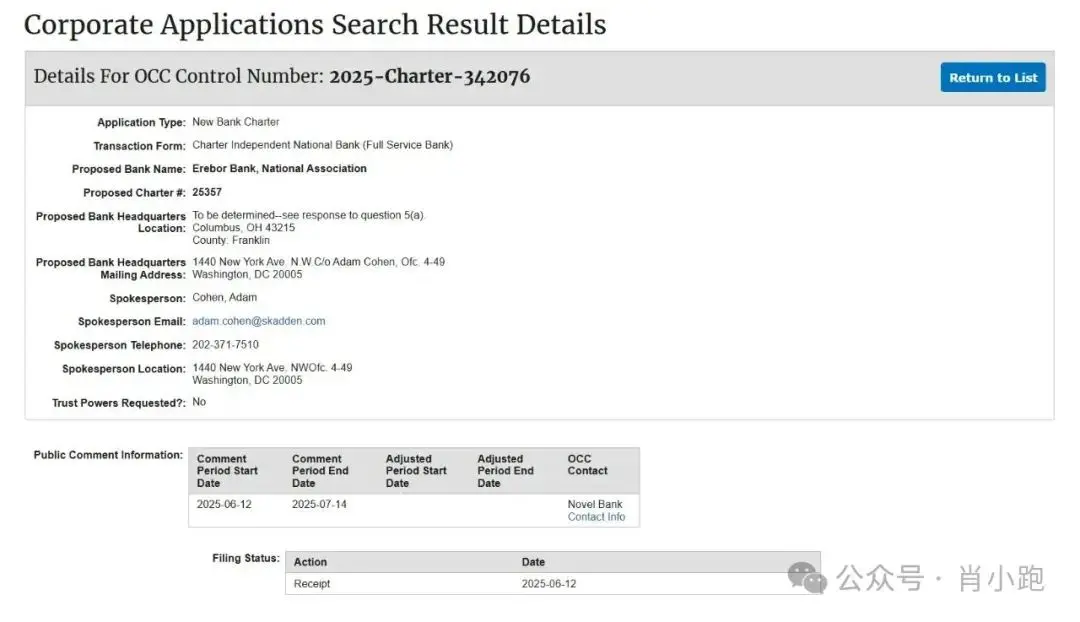

I searched for a long time and found Erebor Bank's application for a national bank charter submitted to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) ("Erebor Bank, NA, Columbus, OH (2025)").

This application reads like an emotionally charged declaration—clearly positioning itself as "the most regulated stablecoin trading service provider," vowing to "fully incorporate stablecoins into the regulatory framework."

Perhaps due to the lessons learned from SVB, from the information available, Erebor claims its risk control strategy is conservatively extreme: keeping a lot of cash on hand, lending little, with loans only up to half of deposits (1:1 reserve ratio, loan-to-deposit ratio controlled at 50%); capital exceeding regulatory levels within three years; all startup funds coming from shareholders' real money, no borrowing, and no dividends for three years.

The target customers are very clear: focusing on tech companies in virtual currency, artificial intelligence, defense, and high-end manufacturing, as well as high-net-worth individuals working for or investing in these companies (aka those considered by traditional banks as "either lacking stable cash flow or too risky to understand"); and "international clients" (aka overseas companies wanting to enter the U.S. financial system but struggling to find a way in; especially those relying on the dollar or wanting to use stablecoins to reduce cross-border transaction risks and costs, aka some clients using U and underground banks), Erebor plans to establish "agency relationships" to become a "super interface" for their access to the dollar system.

The business is also clear: providing deposits and loans, but the collateral is not houses or cars, but Bitcoin and Ethereum.

Stablecoin business is the focus: helping companies "compliantly mint, redeem, and settle stablecoins"; and planning to hold a small amount of virtual currency on its balance sheet—but purely for operational needs (to pay gas fees), not for speculation.

At the same time, they drew a red line: not providing statutory custodial activities that require a trust license (aka only transferring and settling, not holding assets).

It looks like an upgraded version of Silicon Valley Bank 2.0. SVB's logic was: collect deposits → issue loans → earn interest spread. Erebor's logic is: build a bridge between the fiat world and the stablecoin ecosystem, then collect deposits → issue loans → earn interest spread.

04 | Is This Time Different?

That's all the information available. No conclusions can be drawn, only deductions can be made.

First, let's look at the stablecoin business part.

I couldn't find documents indicating whether the deposits are in stablecoins or fiat, but since they "help companies compliantly mint, redeem, and settle stablecoins," then let's assume they are collecting fiat, with part going to issue stablecoins and part going directly to loans. This is equivalent to layering other commercial banking functions on top of Circle. In other words, they are starting to create credit.

If Erebor Bank can truly maintain such a conservative loan-to-deposit ratio and capital adequacy ratio, and completely isolate the stablecoin part of the business—only doing payment settlements, not lending or custodial services; and only serving dollar stablecoins that are regulated USDC, then it seems somewhat reliable. The remaining fiat part of the business can learn from SVB's previous lessons.

I know you want to ask: why can't stablecoin deposits be lent out?

Because "one dollar of stablecoin" and "one dollar of bank deposit" are two different things. The role that "one dollar in a bank" and "one dollar in stablecoin" can play is completely different. Let's understand the deposit multiplier:

If a company deposits $10 million in a bank, the bank only needs to keep 20% as reserves, allowing the remaining $8 million to be lent out. When a second company borrows that $8 million and deposits $6 million back into the same bank, that bank now has $16 million in deposits. This process can be repeated indefinitely.

This is the "alchemy" of the banking system—through the deposit multiplier effect, a $10 million deposit can ultimately create more liquidity.

But stablecoins do not have this kind of "alchemy." In the world of stablecoins, one dollar is just one dollar, and it must be backed by an equivalent dollar; it cannot be amplified out of thin air, which is precisely the definition of stablecoins. No matter how you feel about it, the GENIUS Act has made it clear.

This is the cost of a stablecoin bank: as a bank, it cannot engage in the most profitable activity (credit), and by embracing "stability," it must sacrifice the lending capacity of the banking system.

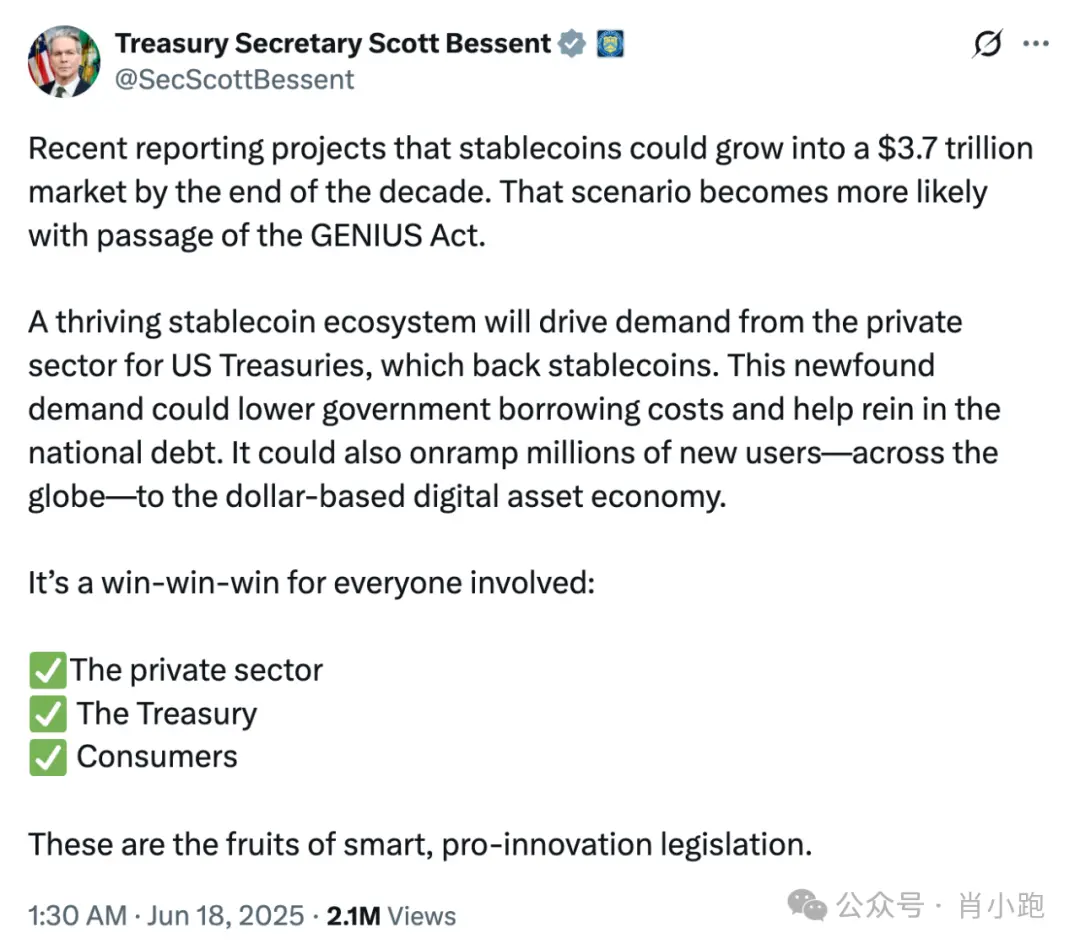

Speaking of this, I recall Professor Bessen's remarks on X: stablecoins are estimated to absorb $3.7 trillion in U.S. Treasury bonds.

If half of that comes from demand or savings accounts, it would account for about 10% of the total bank deposits in the U.S. According to the logic above, this brings a huge trade-off:

The benefit is:

It creates a new massive source of demand for U.S. Treasury bonds (increasing public credit).

The cost is:

It sacrifices the lending capacity of the banking system (weakening private credit).

When everyone withdraws money from banks to buy stablecoins, the banks' ability to create credit through the "deposit multiplier" diminishes. This is essentially an inevitable result of the government's long-term fiscal deficit (there are plenty of historical examples: you can review the impact of money market funds on the banking industry in the 1970s).

05 | Liquidity: A Place Where Ghost Stories Easily Occur

This is just the basic deposit; we haven't even reached the liquidity ghost stories yet.

If stablecoins become the main character on Erebor's balance sheet, although they are pegged to the dollar and other assets, currently, stablecoins do not have federal deposit insurance backing them, nor do they have off-chain liquidity support from the Federal Reserve's discount window.

If stablecoins suddenly decouple and drop, and a significant proportion of Erebor's assets are precisely its reserves or related rights, it could still face an "on-chain bank run"; moreover, depositors wouldn't need to queue, they would just need to click their mouse to withdraw. In such a situation, without FDIC takeover and without central bank rescue, can Erebor withstand it?

Looking at the loan part, this time they did not buy Treasury bonds, but they are making loans secured by cryptocurrencies. But this problem isn't hard to calculate:

Given:

Loan-to-deposit ratio of 50%

Bitcoin collateralization rate could be 60-70%

Bitcoin's daily volatility often exceeds 10%, and in extreme cases can reach 20-30%

Question: How to avoid a death spiral?

Now, let's combine these two things and continue the deduction: if the right side of the balance sheet is stablecoins, and the left side is cryptocurrency collateralized loans (liability side (stablecoins) + asset side (crypto loans)), wow, this combination sounds thrilling.

Let's do a stress test:

A macro event (like a certain individual causing chaos) triggers panic in the crypto market.

Bitcoin plummets by 30%, and Erebor's collateralized loans start to incur massive defaults.

At the same time, the market begins to question the stability of stablecoins, leading to a decoupling.

The value of the stablecoin reserves held by Erebor declines, while loan losses expand.

Depositors begin to panic and withdraw.

Erebor is forced to sell assets at the worst possible time to meet withdrawal demands.

In summary: it is essentially layering leverage and an on-chain bank run accelerator on top of SVB's duration mismatch.

Once the above scenario is triggered, the traditional banking industry's buffer mechanisms do not exist here:

No deposit insurance to stabilize depositor sentiment.

No central bank providing liquidity support.

No interbank lending market to disperse risk.

24/7 digital transactions make it impossible to "pause" a bank run.

This does indeed resemble a "regulatory version of Terra."

06 | Be More Optimistic

I couldn't help but channel my inner old hand. But to be fair, cryptocurrencies and digital assets have become an objective reality. Only three countries in the world completely ban cryptocurrencies. Whether I like it or not, (dollar) stablecoins will experience explosive growth in the foreseeable future.

Erebor aims to create a "hybrid banking model" that aligns with web3 logic while meeting regulatory requirements—enjoying the robust reserves of traditional banks while leveraging all the conveniences and efficiencies of the on-chain world.

From this perspective, Erebor represents an inevitable trend: regardless of who embraces whom, traditional finance and the digital asset ecosystem will attempt to merge.

The question is: who should lead this integration?

Returning to the name Erebor. In Tolkien's story, Smaug was ultimately killed, and the treasures of the Lonely Mountain returned to the dwarves, elves, and humans.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。