Author: Felix Ng

Translation: Wu Says Blockchain Aki Chen

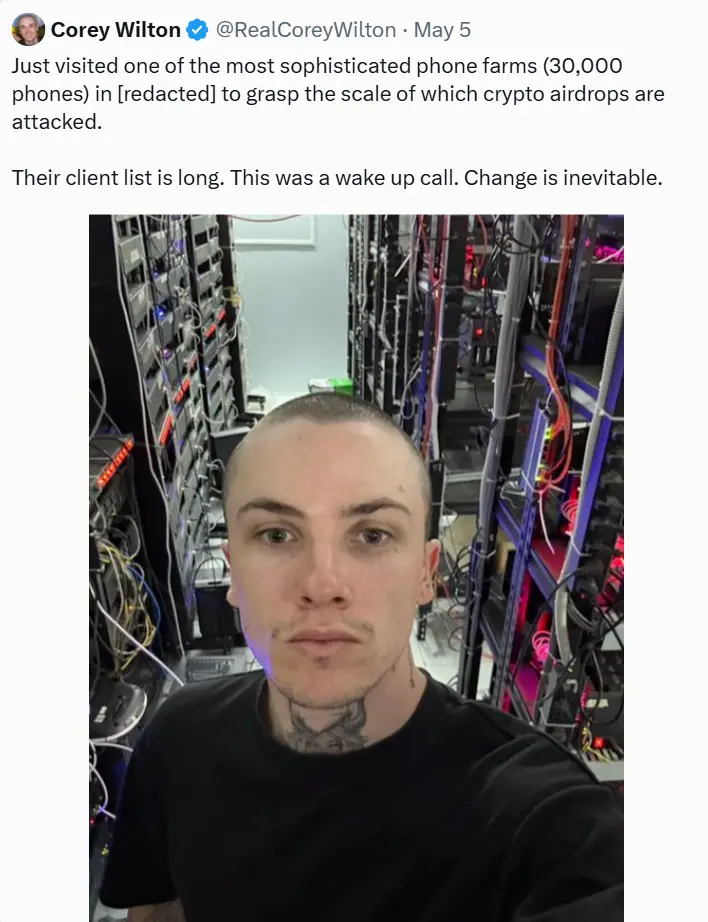

In a "tin shed" with a refrigeration system just a 40-minute drive from Ho Chi Minh City, Mirai Labs CEO Corey Wilton first truly realized the enormous scale of the abuse of crypto airdrops. "It's really chilling," Wilton said in an interview. He had just visited a "phone farm" in southern Vietnam, where he estimated that at least 30,000 smartphones were stacked in a space no larger than a single apartment.

For the past four years, Wilton has hoped to witness firsthand the behind-the-scenes operations that collapsed his flagship NFT horse racing game Pegaxy in 2021. "At that time, Pegaxy was booming, and our daily active users peaked at around 500,000," Wilton recalled. "That's when we started receiving reports about 'robot farms'." These robots could control hundreds of accounts simultaneously, quickly purchasing horses with higher winning odds and repeatedly participating in races to earn in-game currency, which could then be converted into real-world value. "You would see screenshots posted by people showing dozens of applications running on the screen, and similar scenes frequently appeared on social media," he explained.

Pegaxy is an automated horse racing game where fifteen horses compete. Wilton stated that robot farms transformed the game from "who can win" to "who can extract value faster"—changing the game atmosphere and accelerating the project's decline.

On-Site: Unveiling Vietnam's "Professional" Phone Farms

In May of this year, Wilton finally got his wish, with the help of a former Pegaxy player, to exclusively visit a "highly specialized phone farm" in Vietnam. This player had stumbled upon the farm's traces on TikTok.

(Corey Wilton)

"I went to two places, both about a 40-minute drive from where I was, in relatively remote areas," he recalled. "There would definitely be no foreigners going there, and they completely did not want to be discovered." Wilton described one of the locations as a tin shed right next to the street, with the air conditioning set to "as cold as it can get."

Inside the tin shed were metal racks filled with thousands of smartphones, leaving only narrow aisles for employees to pass through. The entire layout resembled a "knockoff" crypto mining farm.

Wilton stated that the operators showed him the "leasing segment" of the business, where clients could rent the phone farm for any purpose they needed. Unlike traditional robot servers, each device in the phone farm is equipped with its own SIM card and device fingerprint, and can disguise its IP geographical location, making it harder to detect, especially in scenarios where each account requires a phone number binding. Additionally, smartphones offer a high cost-performance ratio between computing power and cost, and even if one device is damaged, it can be quickly replaced without significantly affecting overall operations.

Wilton noted that in the cases he witnessed, an operator would control a "master phone" via computer, which was connected to over 500 "slave phones." Whatever operation was performed on the master phone would be synchronized across all slave devices. "Most of their clients actually come from the Web2 industry. For example, K-pop agencies rent these devices to boost traffic; casinos use them to simulate real players, making the games appear more 'real,' but in fact, it's to suppress you and lead you to lose money."

"There are also some Web2 players who bulk farm mobile games, leveling up accounts and then selling these upgraded accounts," he added. However, Wilton stated that the core business of this farm is actually "manufacturing."

The operator would buy damaged or obsolete smartphones at low prices, then modify them through software and other means, ultimately packaging them as "self-service phone farm" devices for sale in overseas markets. The project can produce over 1,000 deployable farm phones each week, with each "phone farm kit" containing about 20 devices. Wilton mentioned that these people do not operate the phones themselves. They do not go out to farm airdrops or perform related operations. Their main business is actually packaging and selling these devices to those overseas who want to operate them from home. All you need to do next is keep these devices online and buy more phones to connect.

Wilton lamented that it is no wonder that "robot-assisted crypto airdrop farming" has become a major ailment in the crypto industry. The so-called crypto airdrop farming refers to obtaining free tokens that should be awarded to real early users by creating a large number of wallet addresses and faking user behavior. Although most crypto airdrops do not require phone number verification, it is still possible to bypass Sybil protection mechanisms through unique device fingerprints and IP addresses.

Such "farming airdrops" often leads to farm users immediately selling off tokens after receiving them, impacting market prices, and making it harder for genuine users to obtain airdrops. Many projects experience a surge of fake active behavior before an airdrop, and once the airdrop is distributed, the number of users and token prices often plummet rapidly.

Frequent Controversies Over Crypto Airdrops, Robot Behavior Widely Criticized

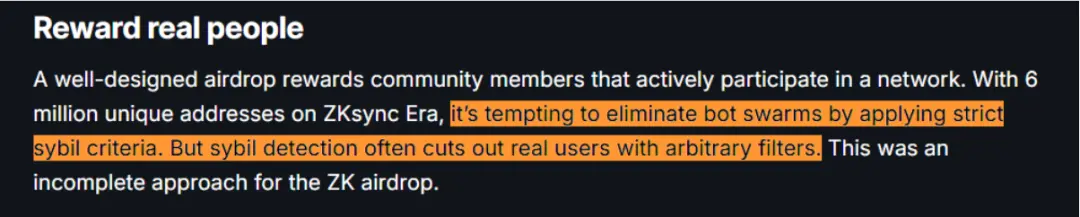

Whether through controlling a large number of phones or using a single computer, robotic behavior has caused significant damage to crypto airdrop activities. Last June, the Ethereum zero-knowledge (ZK) Layer2 scaling project ZKsync faced heavy criticism due to airdrop attacks from numerous robots, with users accusing it of opening the door to "robot farming."

On-chain data analysis platform Lookonchain reported that an "airdrop hunter" claimed over 3 million ZKsync (ZK) tokens through 85 wallet addresses, with a total value of up to $753,000 at the time. Another user publicly bragged on social media that they profited nearly $800,000 through an "extremely efficient $ZK witch attack strategy."

The so-called "witch attack" (Sybil attack) is a security threat behavior where attackers create multiple false identities to seek unfair advantages in network systems. The term originates from a book titled "Sybil," which describes a case of a woman with dissociative identity disorder. Mudit Gupta, the security chief of ZKsync's competitor Polygon, referred to it as "possibly the easiest airdrop to farm and the most farmed airdrop in history," attributing the problem to the lack of anti-robot mechanisms. Despite ZKsync setting seven qualification criteria to prevent witch attacks, the current strategies have become increasingly complex, making it difficult to distinguish between real users and attackers.

However, just last month, Binance provided a different perspective while rectifying robotic behavior in its "Binance Alpha Points" program. "Traditional robots usually follow predictable, repetitive behavior patterns, making them relatively easy to identify," a Binance spokesperson said in an interview. "But with the rise of AI-driven robots, we are now facing a system that closely mimics human behavior—from browsing habits to interaction times—greatly increasing the difficulty of identification." Binance stated that the platform is continuously enhancing its anti-robot efforts and developing new tools to identify abnormal operations from large-scale behavior patterns. For example, address entity association analysis can help identify clusters of wallets controlled by the same actor, even if these wallets appear independent on the surface.

These analyses are particularly crucial for revealing behaviors such as disguised holdings, multisend manipulation, and wash trading—common tactics used by AI-driven robots to fabricate real engagement and false liquidity. The impact is not limited to crypto airdrops; robots have also been accused of flooding the market with countless worthless meme coins. Coinbase's product head Conor Grogan recently pointed out on the X platform: "Most of the tokens launched on PumpFun and LetsBonk platforms are almost entirely controlled by robots." He found that on the meme coin platform LetsBonk, top accounts release a new token on average every three minutes.

Daren Matsuoka, a data scientist and partner at a16z Crypto, believes that witch attacks (Sybil attacks) are actually a problem that has emerged in recent years. "Throughout most of the development of cryptocurrency, we naturally had a certain level of Sybil resistance—because gas fees on these Layer1 blockchains have always been high," he stated in an a16z Crypto podcast in April this year.

"In the past, to qualify for an airdrop, you indeed needed to pay transaction costs of several dollars or even tens of dollars. But with the continuous optimization of infrastructure, the cost of operations has now become very low. I believe this will fundamentally change the dynamics of the attack and defense mechanisms." a16z Crypto's CTO Eddy Lazzarin has been emphasizing the importance of building a "proof of human" mechanism.

“AI can now generate a large number of realistic behavior records. The most advanced robot farms are now almost impossible to reliably identify, and it won't be long before those with medium-level technology become equally undetectable,” Lazzarin wrote in an article in May this year. What Lazzarin is most interested in is building a "proof of personhood" mechanism: it should allow real humans to easily and freely verify their identity while imposing high costs and operational difficulties on robots or fraudsters when they attempt large-scale deception. He mentioned that the iris scanning project World, initiated by Sam Altman, is a typical example of such a mechanism. The core idea of the project is that each person can only register for one World ID, with its uniqueness verified through iris scanning (since everyone's iris is unique).

Lazzarin added in a podcast on the topic of airdrops: “I would love to see more people try systems like World ID, which combines biometric technology with privacy protection mechanisms to limit each person to having only one identity ID.”

However, Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin believes that "one person, one ID" is not a perfect solution, as it means that all historical behaviors could be tied to a single attack point—the key corresponding to that identity. If it is leaked, the risks are significant. At the same time, he pointed out that biometric and government identity information could also be forged.

Why Not Simply Eliminate Crypto Airdrops?

If crypto airdrops are so easily manipulated, the most straightforward choice seems to be to simply eliminate the airdrop mechanism. However, there are also viewpoints that believe airdrops still have their significance. Distributing tokens to real users participating in the protocol not only helps achieve decentralization of project governance but also disperses control through means such as granting voting rights. Additionally, airdrops often generate a lot of buzz. “An obvious reason is: when you distribute a large number of potentially valuable tokens, it attracts a lot of attention, which in itself has a marketing effect,” Lazzarin stated. “Airdrops are essentially a marketing tool.”

Wilton also agreed and pointed out that project teams should anticipate that some users will sell their tokens, which is essentially the marketing cost of acquiring users. The key is to ensure that these users are real people who are “willing to stay long-term.” Meanwhile, Binance believes that automated robots are not entirely harmful. In fact, in certain scenarios, if used properly and transparently, robots can play a positive role—such as providing liquidity, executing strategies on behalf of users, or conducting stress test simulations during audits.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。