Original Title: "The East African Mobile Payment Giant Trapped Between Government Iron Curtain and Dark Industry Abyss"

Original Author: Sleepy.txt, Dongcha Beating

In China, mobile payment is a revolution about "convenience." Whether in bustling cities or remote villages, blue and green QR codes turn our phones into digital wallets. In our perception, mobile operators (China Mobile, China Telecom, China Unicom) are defined merely as "traffic pipelines," while the real financial and payment competition occurs between the two giants, Ant Group and Tencent.

But if you cross the Indian Ocean and step onto the red soil of East Africa, this business logic will be instantly crushed.

Here, operators are not just pipelines; they are banks themselves; SIM cards are not communication credentials; they are bank cards. Whoever controls the communication network controls the financial lifeline of a country. It is this "lifeline-level" temptation that has led to an extremely brutal hunting ground.

In December 2025, the African mobile payment giant M-Pesa was personally blocked by the "national team" in Ethiopia.

To break the traffic islands between operators, M-Pesa launched an ambitious all-network product—"M-PESA LeHulum." In the local language, "LeHulum" means "for everyone." This was originally an experiment with a strong financial inclusion flavor, as M-Pesa hoped to allow every Ethiopian with a mobile phone number to transfer money and make payments freely.

However, this product only lasted a few days.

Less than a week after its launch, Ethiopia's telecom giant—state-owned Ethio Telecom—personally intervened and blocked M-PESA's mobile data access. In the face of absolute administrative will, no matter how sophisticated the business logic, it cannot withstand a severed internet connection.

Why would the "national team" risk the reputation of stifling innovation to strike hard against foreign giants?

The answer lies in that set of dominating data: Ethio Telecom, the "crown prince" of Ethiopia, and its payment platform Telebirr, are an unshakable behemoth. It boasts 54.8 million users, controlling nearly 90% of the market share in the country, with an annual transaction volume reaching 43 billion dollars.

For such a company, when M-Pesa attempted to bypass barriers to connect all users, it no longer saw a competitor but a predator trying to infiltrate the national treasury and touch the financial lifeline.

In the business world, data can sometimes lie, but the contrast that deviates from common sense often points to the truth.

Looking at the user numbers, Safaricom's entry into the Ethiopian market seems like a great success. In just one year, the user count surged by 83.7%, crossing the 11.1 million threshold. However, on the other end of the financial statements, M-Pesa's payment revenue plummeted by 45.6% year-on-year.

This contrast reveals the brutal truth behind the iron curtain: users can only treat foreign operators as a cheap internet card to exploit, while businesses involving custody and clearing remain firmly in the hands of the "national team."

Ethiopia Under the Iron Curtain

In July 2025, a World Bank report titled "Ethiopia Telecom Market Assessment" tore away the last veil of the local market.

Under the objective statements of this report, the Kenyan giant Safaricom appeared like a hunter entering a primeval forest, mistakenly believing it had advanced weapons, unaware that it had already fallen into a carefully designed trap.

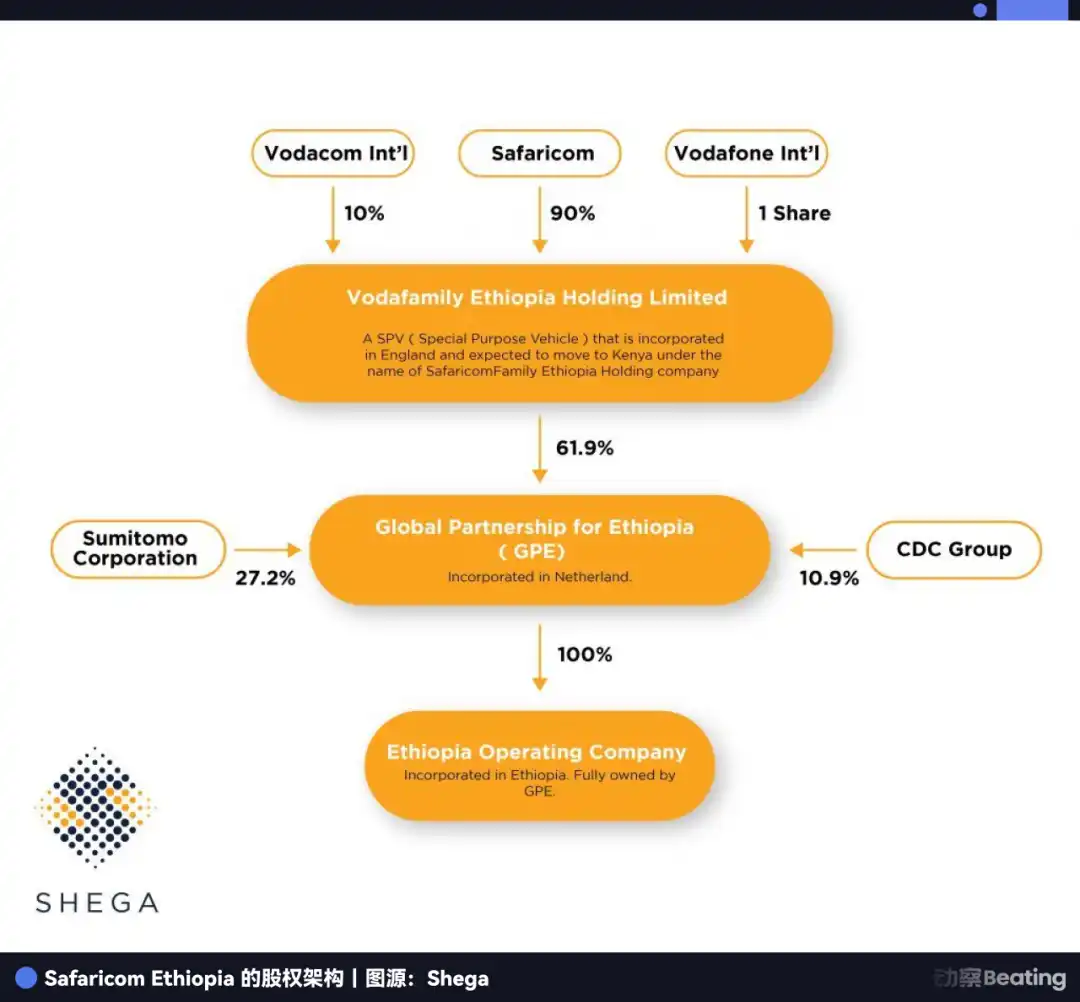

The first trap is the "ticket." To gain entry into Africa's second most populous country, Safaricom paid a staggering 1 billion dollars in licensing fees for 15 years of operating rights and a mobile payment license.

This means that even if the company sells not a single data package, it must bear a fixed amortization cost of about 66.7 million dollars each year. In contrast, its state-owned competitor Ethio Telecom incurred zero costs to obtain the same license.

The second trap is the settlement mechanism known as MTR (Mobile Termination Rate). The logic of this mechanism is simple: when a user from Company A calls a user from Company B, Company A must pay a toll to Company B. As Safaricom is a new player, every call made by its users is essentially a tribute to Ethio Telecom.

According to World Bank estimates, just this one item costs Safaricom nearly 20 million dollars annually in net payments to its largest competitor. Additionally, due to the lack of independent third-party tower companies in Ethiopia, Safaricom has to rent Ethio Telecom's base stations and fiber optics to lay its own network, turning their commercial competition into a comical parasitic relationship: for every new user Safaricom gains and every kilometer of fiber it lays, it is providing blood transfusions to its biggest competitor.

Even under such heavy shackles, Safaricom still managed to break through with superior service, surpassing the 10 million user mark. As the "soft knife" failed to exhaust its opponent, the Ethiopian side began to use administrative means for a dimensional reduction attack.

In the tax sector, the government mandated that all transactions involving the government must be prioritized through Telebirr. As a major taxpayer, when Safaricom went to pay taxes to the government, it was even required to use the competitor Telebirr's payment system.

In the data price war, Ethio Telecom lowered data prices to about 0.16 dollars/GB, nearly 40% lower than the African average (0.25 dollars/GB).

The World Bank characterized this strategy as "predatory pricing," which uses the monopoly position and loss-bearing capacity of state-owned enterprises to deliberately set prices below cost, squeezing cash-strapped competitors out of the market.

In December 2025, when M-Pesa attempted to make a final breakthrough through the LeHulum app, Ethio Telecom finally lost its last patience. It stopped beating around the bush and stopped following the rules. The severed internet connection became the end of this years-long hunting ground.

Why is the Ethiopian government so aggressive, even willing to tear up global commitments to telecom liberalization?

On the power chessboard in Addis Ababa, mobile payment has never been a question of "convenience." The core issue lies in two words: foreign exchange and surveillance.

Ethiopia sees up to 6 billion dollars in remittances flowing in through underground channels each year, with the most troublesome for the government being Hawala, an ancient underground banking system prevalent in the Middle East and Africa. It does not rely on banks but on interpersonal credit, completely bypassing regulatory radars.

For the Ethiopian government, which is extremely short of foreign exchange, Telebirr is not just a wallet; it is a "financial trap." The government urgently needs to use this official channel to reclaim every dollar scattered among the people.

An even more secret ambition lies in central bank digital currency (CBDC). In the government's grand vision, Telebirr, with its 54.8 million users, will be the only legal outlet for future digital currency issuance. In the logic of power, financial infrastructure must be in its own hands, and no foreign capital is allowed to touch the country's credit foundation.

However, does this "absolute sense of security" built under the iron curtain really bring prosperity?

In July 2024, Ethiopia implemented currency reform, causing the local currency exchange rate to plummet nearly threefold. Ethio Telecom, burdened with massive dollar debts to suppliers like Huawei and ZTE, saw its foreign exchange losses soar from 3 billion birr to 42 billion birr, an increase of 1825%, leading to a 70% drop in after-tax profits.

This is the true face under the iron curtain: the government stifled competition for a sense of security, foreign capital bled under unfair rules, and state-owned enterprises were severely injured in the currency storm. For ordinary users, they have no choice but to continue using the designated applications.

The Tragedy of Freedom in Kenya

If Ethiopia's iron curtain is suffocating, then will neighboring Kenya, which practices a free market, be a promised land for business? After all, this is the home of M-Pesa, its proud stronghold.

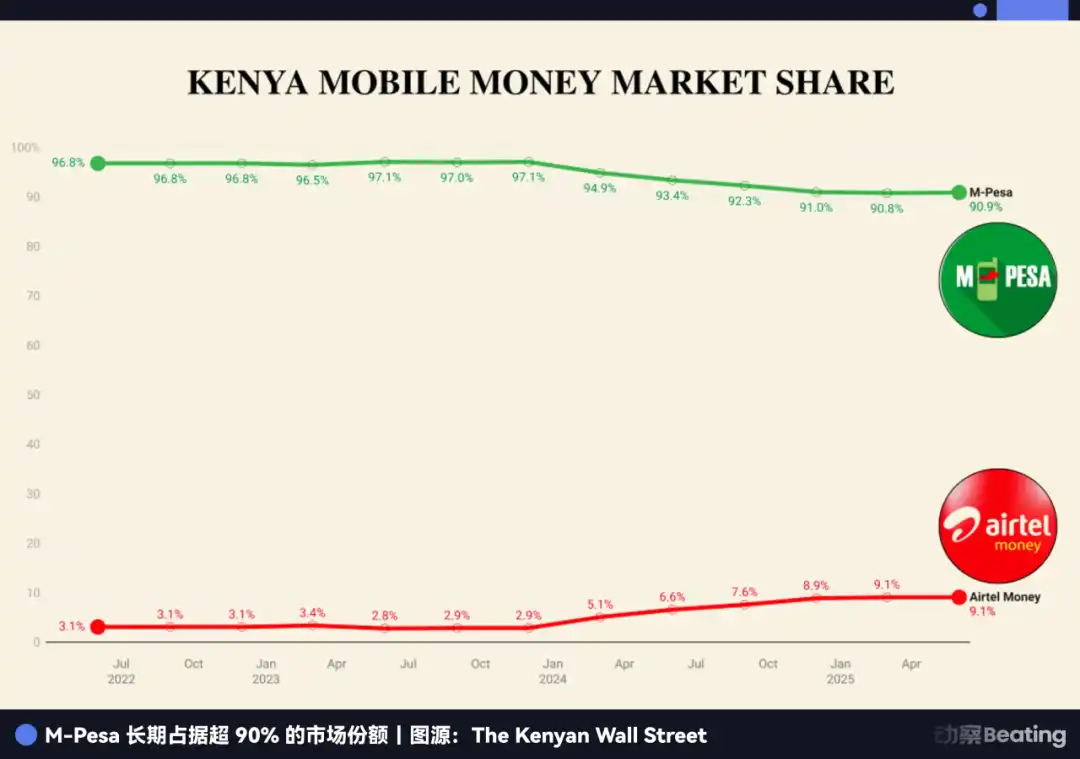

Here, M-Pesa does not face any administrative blockades. It occupies 90% of the market share, with nearly 60% of Kenya's GDP flowing through this network. It is not just a payment tool; it is the water, electricity, and gas of the country's financial system.

But when regulation is long absent, this absolute freedom ultimately devolves into absolute chaos. The pipeline that M-Pesa originally paved for inclusive finance has now become an uncontrolled highway for crime.

The first to speed down this highway is gambling. In Kenya, gambling is a tacitly accepted money-guzzling beast, and M-Pesa is its largest funding channel, with as much as 1.5 billion dollars (169.1 billion Kenyan shillings) flowing into the gambling network each year.

The Kenyan government heavily relies on the massive tax revenue provided by the gambling industry, thus turning a blind eye to the source of funds, making M-Pesa a paradise for criminals. The government collects taxes, gambling companies make money, and M-Pesa takes the fees. In this perfect commercial closed loop, only the social security is paying the price.

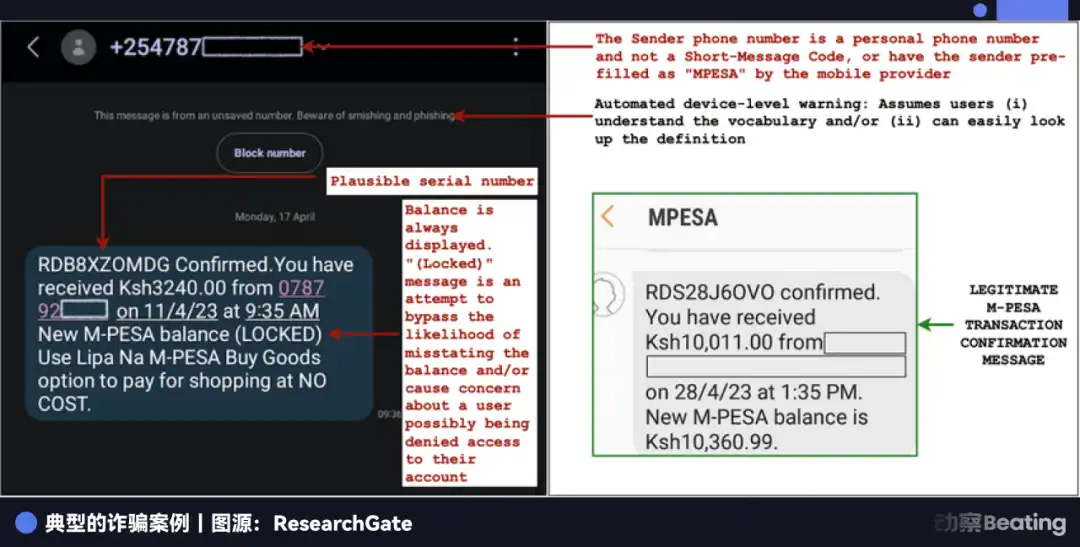

More alarming than money laundering is the rampant fraud. In 2024, fraud losses related to M-Pesa surged by 344% year-on-year. M-Pesa has 30 million users in this country, with over 80% of users having been targeted by fraud rings.

Moreover, the current scams have undergone several iterations; they are no longer satisfied with stealing the balance in your wallet but directly use your identity to apply for loans.

The most typical case is the attack on the loan service launched by Safaricom. Criminal gangs illegally obtained 123,000 SIM cards and exploited M-Pesa's credit loopholes to apply for overdraft loans on a large scale, instantly siphoning off millions of dollars.

Why can criminals so precisely pass identity verification? The answer points to Safaricom's internal issues.

In 2024, the company fired 113 employees at once for participating in fraud. Those who held user privacy data and had backend access were becoming key links in the black industrial chain; any sophisticated technical firewall is as thin as a cicada's wing in the face of human greed.

Common Underground Roots

When we try to explain the iron curtain of Ethiopia and the abyss of Kenya with civilized business logic, we often overlook the deeper, more disturbing world beneath the surface.

Technology is neutral, but human nature is not.

In the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia, illegal gold mines are expanding like a tumor across the wilderness. Investigations reveal that in those vast mining areas, visible even from satellites, legitimate order has long been pushed aside, replaced by a violent network woven together by mysterious foreign investors and local armed groups.

Mysterious "foreign investors" provide millions of dollars in funding to purchase heavy excavation equipment; local military forces are responsible for guarding checkpoints, turning the mining areas into independent states.

Every day, thousands of miners work under the threat of guns, and the gold they extract does not enter the central bank's vaults but flows continuously to Sudan or the UAE through military-controlled smuggling routes, transforming into billions of dollars in dirty money.

With the convenience of mobile payments—split transactions, instant processing, low costs, and multiple points of payment—huge smuggling funds are broken down into smaller amounts, quietly flowing back. Under the temptation of gold prices exceeding 4,000 dollars per ounce, the so-called inclusive finance ultimately became the most efficient harvesting tool for illegal mineral monetization.

More difficult to trace than gold is cash. Ethiopia sees up to 6 billion dollars in remittances flowing in each year, supporting countless families. However, due to a significant price difference of about 15% between the official exchange rate and the black market rate, the vast majority of funds do not go through banks but flow into Hawala.

In an effort to combat money laundering, the Ethiopian central bank has publicly cracked down on Somali remittance companies, accusing them of funding illegal activities. Yet for the poor in remote areas, the scarcity of formal bank branches makes these underground networks their only option.

If you block it, you cut off the livelihoods of the poor; if you allow it, it becomes a breeding ground for terrorists and money launderers. In this vast mobile payment network with 118 million dormant accounts, funds flow like mercury, completely unregulated.

If gold and money laundering are merely a game of money, then on the other end of the mobile payment network, blood flows.

In 2022, in the forests of northern Malawi, 29 bodies were discovered in an abandoned truck. They were all young men from Ethiopia, who had originally attempted to smuggle themselves to South Africa via the notorious southern route in search of a way out, only to suffocate to death.

This is not just a simple smuggling tragedy; investigations show that mobile payment technology is inadvertently reshaping the business model of the bloody human trafficking industry.

In the past, smugglers required a one-time cash payment, which was high-risk and had a high threshold. Now, using tools like M-Pesa, criminal gangs have invented an "installment payment" smuggling model. The real-time nature of mobile payments allows smugglers to manage human trafficking like a supply chain, paying at each stop. If a family member's transfer does not arrive, the smuggler may abandon, abuse, or even kill the trafficked person.

Whether Ethiopia tries to monitor everything with an iron curtain or Kenya attempts to connect everything with freedom, underground currents always find cracks; they transcend borders and disregard systems.

On these digital highways built by M-Pesa and Telebirr, not only do the ideals of inclusive finance run, but also the evils of money laundering, smuggling, and human trafficking. Technology has paved the road, but it cannot control whether the vehicles running on it carry life-saving food or cold corpses.

The Choice of Capital

Faced with such a distorted and fragmented East African market, international capital's instincts are always the most sensitive and ruthless.

In December, South African telecom giant Vodacom announced a shocking decision, investing 2.1 billion dollars to increase its stake in Safaricom from 35% to 55%, gaining absolute control.

But this is not an ambitious offensive; it feels more like a desperate defense. Safaricom's domestic business in Kenya remains a cash cow, with a net profit of 58.2 billion shillings (about 45 million dollars) in the first half of 2025, with M-Pesa contributing half of that. However, in Ethiopia, it is bleeding at an astonishing rate.

Financial reports show that Safaricom Ethiopia lost 15.5 billion shillings in just six months, with M-Pesa's business revenue plummeting by 45.6% year-on-year.

This has put Vodacom in a very passive position; it cannot watch as Ethiopia, a bottomless pit, drags down the cash cow of Kenya.

Vodacom's heavy investment for control is clear; it needs to directly intervene in management through absolute control. It must either force a stop-loss in Ethiopia or use its multinational resources to restructure the business. This 2.1 billion dollars is essentially a lifeline to preserve the profit base of its Kenyan stronghold.

In contrast to Vodacom's forced takeover to save Kenya, another shareholder—Japan's Sumitomo Corporation—has made a more foreboding choice. As the second-largest shareholder, Sumitomo has purchased a 10-year political risk insurance policy for its investment in Ethiopia.

This insurance does not cover commercial losses but specifically insures against "government confiscation of assets," "currency inconvertibility," and "default risk."

In the international investment community, this is seen as the highest level of red alert. Even after years of deepening ties in Africa, the Japanese consortium has completely lost faith in the rule of law here. In their contingency plans, government expropriation of assets or currency becoming worthless is no longer an "if," but a "when."

However, the giants of the old world may have miscalculated one thing. While they are still meticulously calculating market shares of local currencies, stablecoins are deconstructing everything in a way that is a dimensional reduction attack.

As Kenyan software engineers begin to demand salaries in stablecoins to combat inflation, and wealthy Ethiopians use stablecoins to bypass foreign exchange controls to transfer assets, the foundation on which M-Pesa relies—the local currency system—is collapsing from within.

Users no longer need an electronic wallet that can only hold depreciating currency; they need a digital dollar that can retain value. In Ethiopia, even with the government's strict prohibitions, retail trading volume of stablecoins has surged by 180%.

What Vodacom bought for 2.1 billion dollars may just be an expired ticket to the old world. Meanwhile, the ship to the new world has quietly set sail.

The Third Path

In this ancient yet restless land of East Africa, mobile payments are writing the most intense confrontation in human commercial history in an unprecedented manner. But peeling away the glamorous packaging of "inclusive finance," the core reveals a history of power and greed.

On one side is Ethiopia's "blockade," guarding financial sovereignty with administrative towers, yet inadvertently stifling future possibilities; on the other side is Kenya's "mad dash," shattering the safe red lines with the iron hooves of the market, yet leaving ordinary people as lambs to the slaughter in the chaos.

This is the most paradoxical aspect of Africa's mobile payment revolution: it has made the flow of funds unprecedentedly simple, yet made ordinary people's lives unprecedentedly complex.

Those who shout revolution discuss changing the world over cups of capital. Meanwhile, those who truly live on that land must face digitized fraud, installment payment human trafficking, and the ever-present threat of severed internet connections.

Between the iron curtain and the abyss, the third path has yet to emerge.

We once hoped that technology could eliminate injustice, but ultimately discovered that technology is merely an amplifier. It amplifies the arrogance of power and the ferocity of capital.

On the ship to the new world, we need not only a powerful engine but also the often-overlooked rope called "bottom line." Otherwise, this grand digital process may ultimately leave behind not a monument to inclusivity but a pile of expensive wreckage.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。