For early founders, knowing how to balance value capture and the velocity of capital flow is the secret to survival.

Written by: Joel John

Translated by: Luffy, Foresight News

Some might say it's an addiction, but I often find myself unconsciously pondering: "How much coffee is too much?" At some point, the caffeine level in your blood may have reached a point where consuming more coffee yields less return than simply hydrating. The brain thinks it needs more of this anxiety-inducing coffee, but the body is actually better suited to the simplest, most basic liquid known to humanity: water.

The market is similar. We often think that more good things will lead to better outcomes. But returning to a new normal may be the urgent priority. When tariffs stabilize at predictable levels, industries adapt and recalibrate to reach a new normal; when venture capital slows down, weaker companies are eliminated, creating more stability for those that remain. Why do I say this? Just like drinking coffee, we have reached a local peak in the velocity of capital flow and fee extraction. What the industry needs to do now is figure out how to sustainably improve both aspects.

The market exhibits this fatigue in some peculiar forms. Venture capitalists argue that we don't need more infrastructure; marketers say we should focus on consumers; analysts suggest we need products with economic fundamentals; traders hope for more market volatility. Like many things in life, the truth lies hidden in the motivations that drive people to think this way.

Objectively, we can view blockchain not only from the perspective of scale or throughput but also through the lens of transaction fees. The core of blockchain is a network that facilitates the flow of capital. They are thriving trading ecosystems that operate in real-time on a global scale. Bitcoin fulfills this function well and has earned the status of hard currency, but what about other applications?

In other words, what happens to the digital economy when capital flows at the speed of information on the internet? How will the formation and allocation of capital evolve when transferring funds becomes as easy as a click? In today's article, I attempt to find answers to these questions.

Digital Marketplaces and Smoke Screens

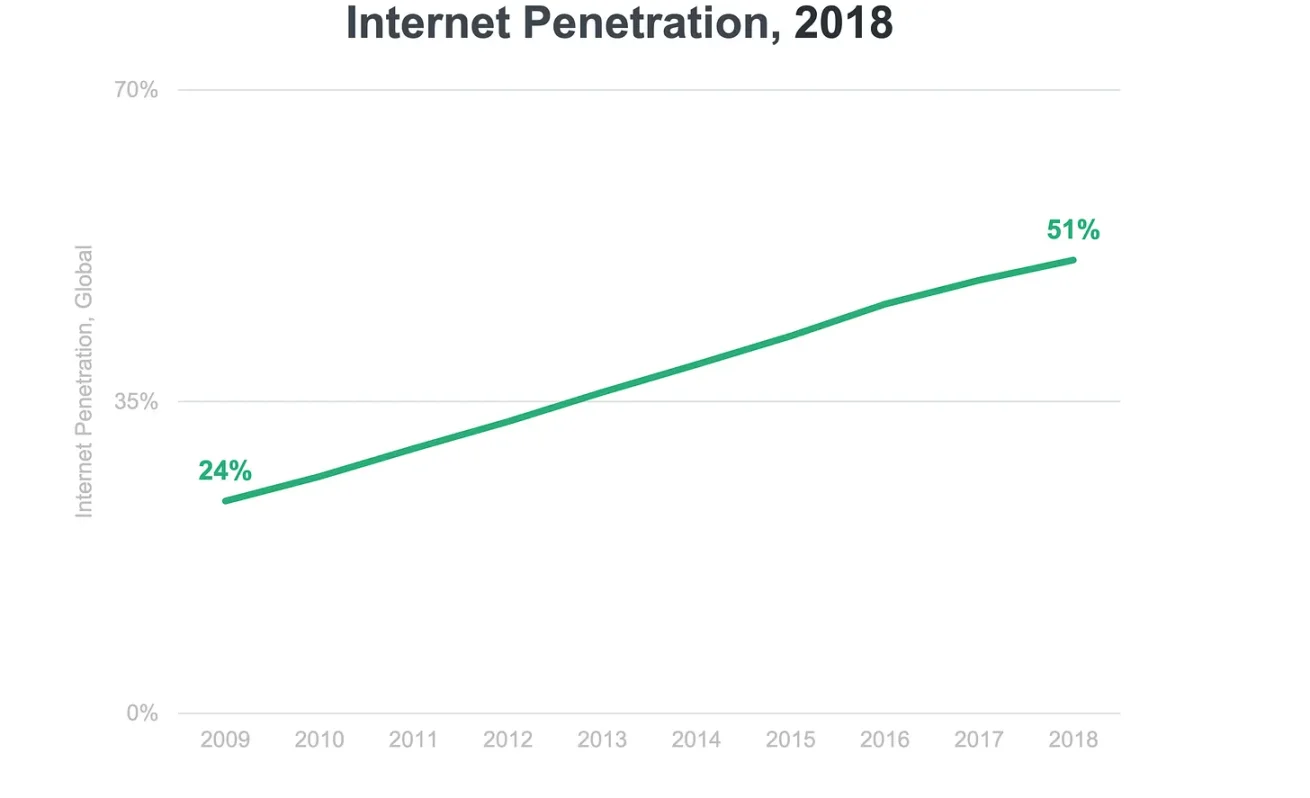

Internet penetration rate, image source: Bond Capital 2019 report

The internet is a trading system; you just don't realize you're trading. In 2001, Google's ad revenue was $70 million, with each user contributing about $1.07. By 2019, this figure skyrocketed to $133 billion, or about $36 per user. In 2004, the year of Google's IPO, 99% of its revenue came from advertising. In many ways, the development of the web is a story of how an advertising network extracted value from each user 40 times over in 25 years.

You might think this is no big deal, but every time you scroll your screen, search for content, or post information, you are creating a commodity: human attention. At any given moment, you can only focus on one thing, maybe two or three at most. The attention economy aims to monetize this limited resource in two key ways:

First, by optimizing the collection of information about individuals. This is easy to achieve on social media, as users provide feedback to platforms (like X, Instagram, or TikTok) based on the types of content they spend time on.

Second, by optimizing user engagement time. Netflix claims that sleep is their competitor, and they are not joking. By 2024, the average person spends 2 hours a day on the platform, with 18 minutes spent deciding what to watch.

In short, you are not the customer; you are the product.

In any given year, you will spend the equivalent of four days scrolling through media apps just to decide what to watch. I wouldn't even want to calculate how much time people spend on dating apps. The internet is interesting because we have figured out how to extract value by keeping users engaged longer and sharing more of their information. The reason ordinary people don't know how this works is that they don't need to know.

Imagine internet platforms as vast digital marketplaces. When you spend time on apps like X or Meta, businesses pay the mall owners (Musk or Zuckerberg) for the chance that you might make a purchase. In these digital marketplaces, attention is equivalent to foot traffic. Why is this important? Because in the early 21st century, those more "primitive" malls faced a problem: users didn't have debit cards, and businesses couldn't accept direct digital payments. Trust and infrastructure were lacking. So, platforms didn't charge users directly but monetized indirectly through advertising.

Advertising became a workaround for the internet, which was not yet ready for seamless payments. In turn, it created a new economy that operated in the digital environment.

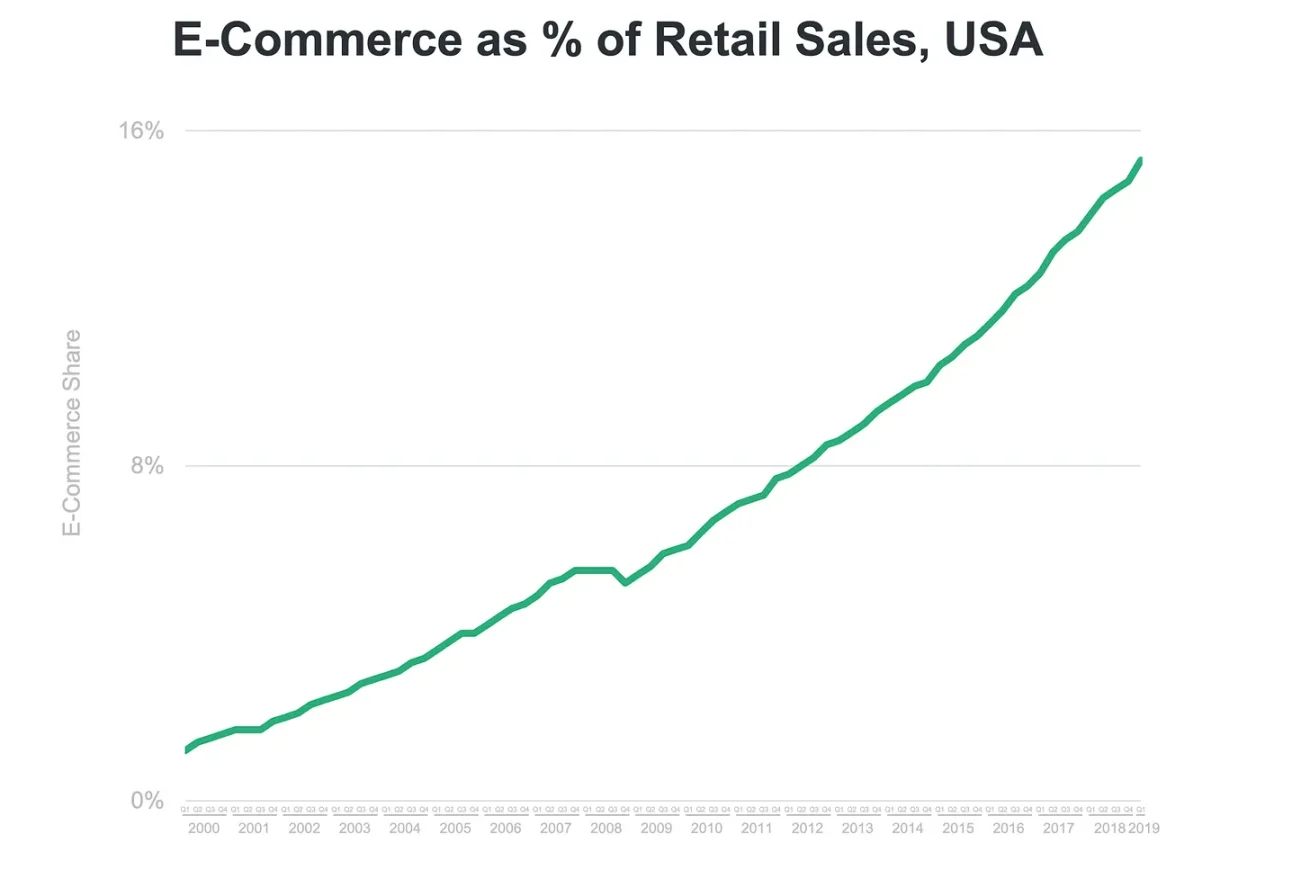

The proportion of the electronic economy in retail. Image source: Bond Capital 2019 report

How does this system work? Every time you shop online, merchants pay a transaction fee to the platform (the digital marketplace). On platforms like Google, this fee is reflected in advertising spending. In other words, how users pay for products doesn't matter. What matters is that the platform earns revenue from merchants through bank transfers and debit cards. Merchants have employees to handle payment and logistics issues. And users? They are busy avoiding malware from LimeWire. So this model works well. Platforms don't need to teach users how to pay; they just need to ensure that merchants pay them.

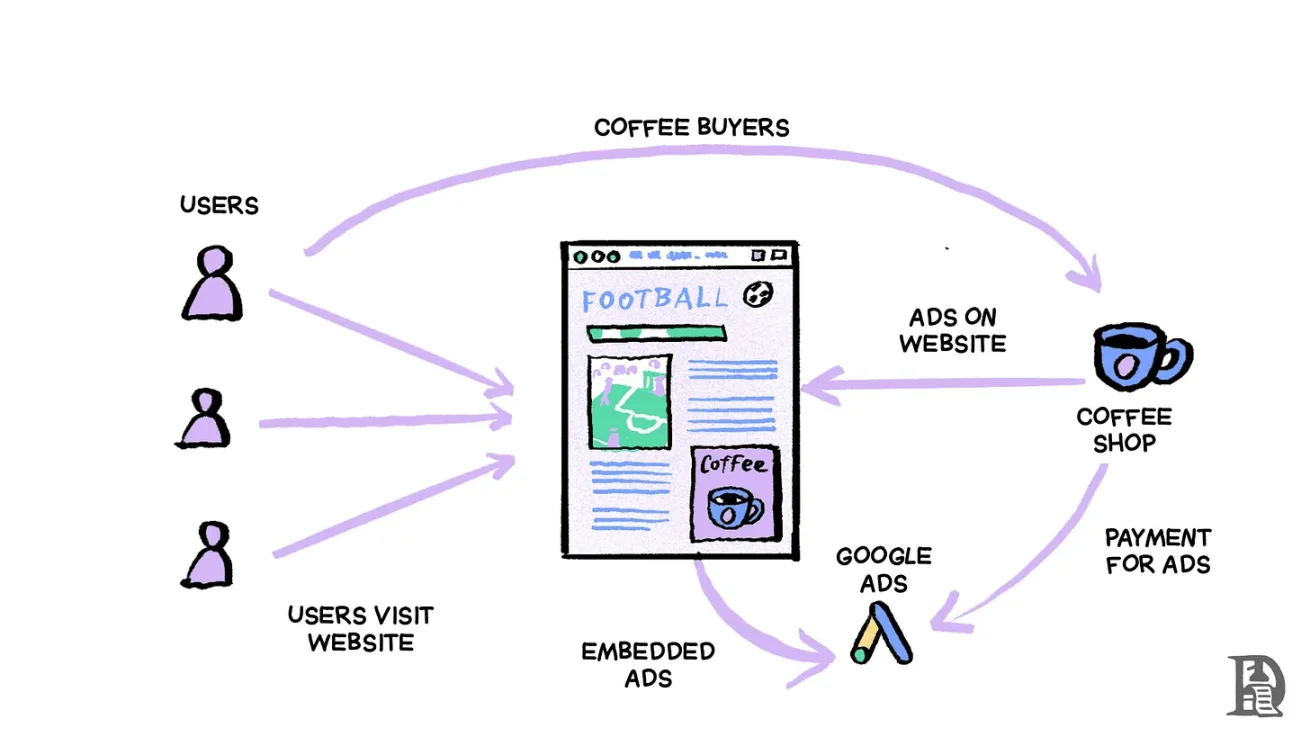

Current value flow in the internet attention economy

Fast forward to 2020, when the internet was obsessed with a magical NFT called Bored Ape. OpenSea became the new marketplace, Ethereum was the payment network, and users flocked in droves. But no one really figured out how to charge fees from these users without involving complex issues like capital entry processes, on-chain fees, Ethereum price fluctuations, transaction signatures, private keys, and setting up MetaMask.

The crypto products that drove market growth in the following years had one thing in common: they lowered the barriers to entry.

Solana made it possible to approve transactions without multiple manual confirmations.

Privy allowed users to hold wallets without worrying about private key issues.

Pump.fun enabled people to create meme coins in minutes.

The market favors simple and user-friendly products, as evidenced by the rise of stablecoins.

The Velocity of Capital Flow and Network Moats

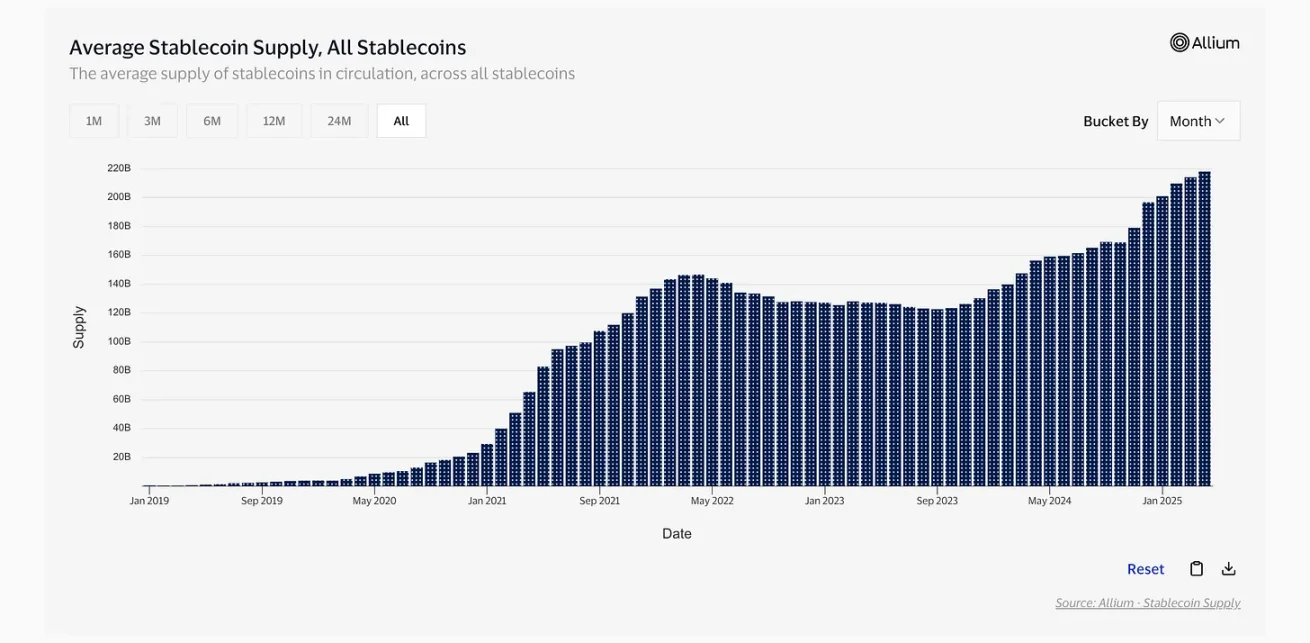

Image source: Visa

In January 2019, the total supply of stablecoins was only $500 million, roughly equivalent to the valuation of some meme coins in recent months. Today, that number has reached $220 billion. Growing 500 times in six years is a pace rarely seen in a person's career. But not only has the supply increased significantly, but the profitability of stablecoins has also surged. In just the past 24 hours, Tether and Circle generated a total of $24 million in fees. In comparison: Solana's fees were $1.19 million, Ethereum's were $975,000, and Bitcoin's were $560,000.

This seems like a comparison of different categories, as one is a financial product (stablecoins) while the others are payment networks. But when you consider that these two stablecoin issuers generated nearly $7.5 billion in revenue just last year, you can glean some insights. When you also consider that $33 trillion was transferred through stablecoins via 540 million transactions and 240 million active unique addresses, these numbers become even more impressive.

However, the revenue generated by stablecoins does not come from users but from the returns generated by a combination of U.S. Treasury bonds and money market funds. This does not include the income from minting and burning stablecoins.

When users pay with stablecoins, the fees are unrelated to the amount. On Solana, whether you send $10, $1,000, or $10,000, the transaction cost is the same: $0.05. This is different from using Visa or Mastercard, where transaction fees are expected to be between 0.5% and 1.5%. However, stablecoins remain one of the most profitable businesses in the cryptocurrency space. Why is that? They solve the complexity issues users face in three ways:

They provide people around the world access to a highly sought-after asset (the U.S. dollar).

Stablecoins have the highest velocity of circulation. Whether through PayPal, Wise, or bank transfers, stablecoins facilitate faster cross-border transactions.

Products like Kast allow you to use stablecoins to pay for real-life expenses, and their network effects mean more users feel comfortable receiving and making payments with stablecoins.

I find it interesting that in an industry obsessed with decentralization, the most profitable part is earning income through centralized holdings of U.S. Treasury bonds and issuing dollars on-chain. But that is the essence of technology. Ordinary people are not as concerned about how decentralized a product is as they are about what it can do; they are also not as concerned about the purity test of L2 as they are about transaction costs. From these perspectives, stablecoins are simply a better dollar.

Its innovation lies not only in issuing dollars on-chain but also in abstracting the complexity of fees, as we saw in previous generations of advertising platforms. The true brilliance of stablecoins lies in finding a reason to deposit large amounts of dollars into U.S. Treasury bonds and surviving on the returns generated by those bonds.

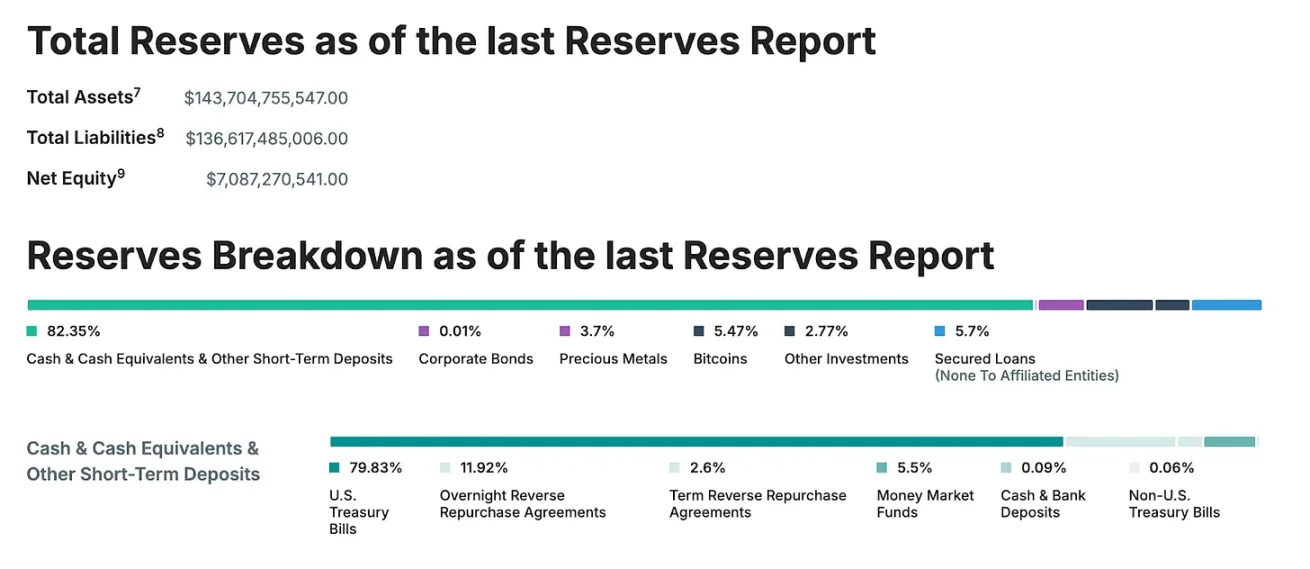

Image source: Tether's proof report

Stablecoins seem to be the winners. But if you look at it from the perspective of capital flow velocity, they are not superior to traditional payment networks. In comparison to the $33 trillion transferred on-chain via stablecoins, traditional payment networks processed $13.2 trillion through Visa and $9.75 trillion through Mastercard just last year. So, together, they handled nearly $22 trillion in total funds annually. Compared to the 5.4 billion transactions completed by stablecoins last year, Visa alone processed 233 billion transactions. One might argue that given the lower transaction costs, the amount of funds transferred on-chain should be much higher, but traditional payment networks outperform in both transaction volume and count.

From the perspective of capital flow velocity alone, traditional payment networks perform better. But this is not because their technology is inherently superior; rather, it is due to the entrenched network effects developed over decades. You can show up at a matcha shop in Japan, a French baguette bakery in France, or the best cycling spots in Dubai and pay using the same payment tool: a debit or credit card.

Then try paying with stablecoins stored on Polygon or Arbitrum and let me know how that goes. (Note: I actually tried this, and it took 20 minutes to wait for a cross-chain bridge transaction to complete.)

The reason I bring this up is that our industry often argues that stablecoins are inherently superior to fiat currency transactions in all use cases. But in reality, the fees charged by Visa or Mastercard are comparable to those charged by any exit channel that converts on-chain stablecoins into real-world dollars. This is akin to arguing that digital media is superior to print newspapers in all use cases, which is not the case. If you live in a remote mountainous area without access to a computer and the internet, then print newspapers are the best way to obtain media information.

Similarly, if you do not frequently engage in on-chain activities, debit cards are the best payment method. But if you are often online or conducting on-chain operations, the experience may be significantly better. For founders designing the digital economy in the coming years, knowing how to distinguish between on-chain and off-chain, as well as understanding the different forms in which value can be captured, may be key.

The Relationship Between Velocity and Fees

So, how should founders think about fee structures and expanding market share? Should we be obsessed with bringing people on-chain, or should we find a way to make these on-chain elements useful? There are two ways of thinking about this, both of which have reasonable and meaningful arguments to support them.

For lending and staking, fees are assumed to be 10% of the rewards or interest generated.

One perspective is that revenue in the cryptocurrency space may be seasonal, but capital flow velocity is extremely high. In traditional markets, people believe that increasing fees will reduce capital flow velocity. However, some of the most speculative parts of cryptocurrency come with very high fees. During the NFT boom, OpenSea charged a 5% royalty share, and Friend-Tech charged nearly 50% of revenue share. In places where profit is the main driver, individuals are willing to pay higher transaction fees and simply view transaction costs as a cost of doing business.

Nowhere is this trend more evident than in Telegram trading bots. In the past few quarters, products like Photon, GMGN, and Maestrobot have collectively earned hundreds of millions of dollars for three core reasons:

The seasonality of meme coins means users have a new market (like the NFT market in 2020) to speculate and profit.

Integrating wallets into Telegram and making the chat-based trading interface user-friendly has improved user experience, allowing users to trade via mobile devices.

Lower transaction costs and faster speeds on Solana mean users can trade back and forth multiple times in a short period, leading to compounded profit growth.

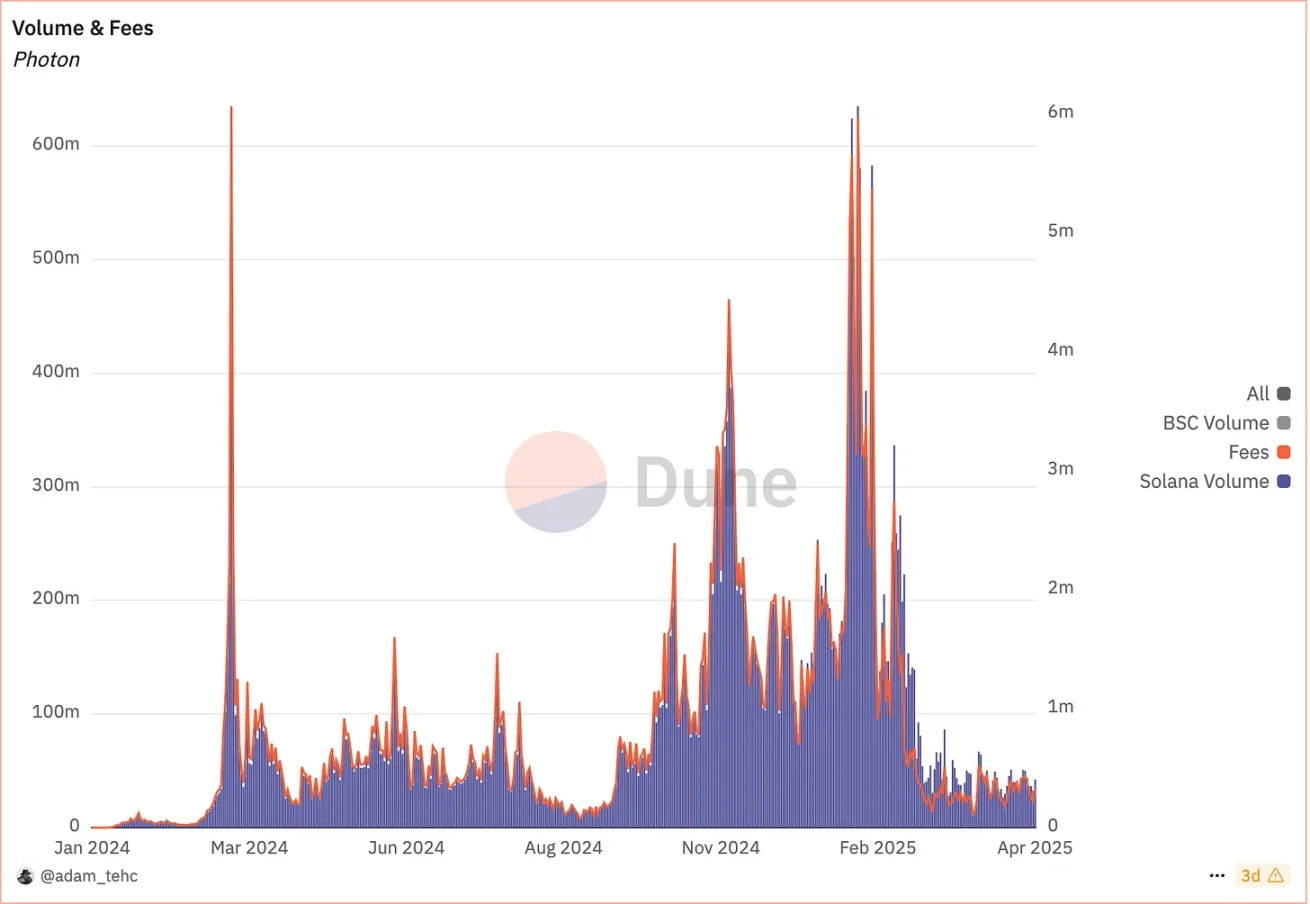

This innovation is not just about the assets themselves but also about the cheaper and faster transactions on Solana and the behavioral changes brought about by the dissemination channels provided by Telegram. Seasonal applications often struggle to maintain user stickiness, but the capital flow velocity is so high that it doesn't matter if the industry collapses in eight to nine months. Users will pay a high premium, and those who sell shovels during a gold rush often do quite well. The chart below illustrates the case of Photon.

Photon is one of many applications focused on improving trading infrastructure during last year's meme coin surge. Data source: Dune

It is important to note that charging high fees in a high capital flow velocity environment is only feasible in the absence of competition. If time is long enough, the market will generate enough competition to lower fees. This is why the fees for perpetual contract exchanges are on a downward trend. For meme coin market-oriented products, the main players maintain high fees before competition fully arrives and the meme coin trading market declines. The impact of Blur on OpenSea's model is an example of fees decreasing when competition emerges.

Another perspective is that sticky capital sources, like liquidity providers on Uniswap or depositors seeking Ethereum yields on Aave and Lido, are the ideal target market. In these types of products, capital flow velocity is often much lower. Users deposit funds every few months and then do not pay attention to them. Therefore, the fees charged by these products tend to be higher. Aave charges users 10% of the interest they earn, Lido takes 10% of staking rewards but shares half with node operators, and Jito also charges a 10% fee.

On the internet, there is a conservative rule regarding capital flow velocity and collectible fees: the more times capital changes hands, the lower the implicit transaction fees.

If capital is idle, users may be charged 10% of their income as fees. Seasonal markets or high transaction speed products (like HyperLiquid or Binance) can generate hundreds of millions in revenue because users conduct hundreds of repeat transactions in a single day.

Assuming no profit, with a transaction cost of 1%, a user only needs to make 69 transactions to end up with 50% of their initial capital. If each transaction incurs a 2% loss, the user would need to make 23 transactions. This somewhat explains why we see a downward trend in transaction fees on platforms. Platforms like Lighter have moved towards zero fees, and Robinhood is similar. If these trends continue, we will eventually reach a critical point where businesses will have to find other ways to generate revenue while ensuring users remain unaware of transaction costs, much like today's dollar stablecoins.

High velocity products monetize through compounding fees, while low velocity products tend to profit through transaction channels. In other words, the fewer opportunities a protocol has to touch the same dollar in any given day, the higher the revenue it needs to earn from that dollar to maintain sustainability.

Speculative-driven seasonal pricing errors may lead users to pay high fees for high velocity products. But what about non-seasonal products? What would happen with on-chain stocks and commodities? I had the opportunity to sit down with the founder of a company in our portfolio to discuss this. Usman from Orogold has been working on building a gold-related business on-chain. The following content is inspired by a conversation I had with him over coffee.

On-Chain Commodities

People often believe that tokenization can unlock tremendous liquidity for financial instruments. This is why many venture capitalists holding illiquid equity believe that venture capital equity should be tokenized, which is understandable. But if the meme coin market has taught us anything, it is that liquidity in the cryptocurrency space often gets dispersed across millions of assets. And when this happens, there is almost no fair price discovery space. As a founder, would you want to compete for liquidity with Fartcoin? I doubt it, at least not in the seed stage.

So why are exchanges like Coinbase and Robinhood eager to bring stocks on-chain? The reason is simple: two forces are at play. First, the market is global and operates around the clock. Assets like Bitcoin have become a macro hedging tool as liquidity hedge funds want to hold an asset that can move in sync when the stock market is about to decline. Last year, Bitcoin's price fluctuated before the collapse of the yen arbitrage trade, and it also preemptively reflected the market's pricing of Trump's tariffs. The market needs a trading venue that can operate anytime, anywhere, and on-chain stocks can fulfill that role.

Second, the total market capitalization of cryptocurrencies has now exceeded $2 trillion. This value needs a liquid outlet and cannot always exist in the form of dollars, nor can it always be in the form of real-world asset (RWA) lending, as their risk profiles vary significantly. On-chain commodities and stocks provide a safe place for these funds. Of course, not all commodities and stocks are the same; the market size for uranium is far smaller than that for gold.

This is why we are (likely) going to see a top-down approach, where major assets and commodities are tokenized first. Which scenario do you think is more likely to be adopted on-chain? The S&P 500 index or an early venture capital equity index? I lean towards the former.

When it comes to commodities, some are easier to find product-market fit (PMF) than others. Gold, due to its long history and the fact that it is hoarded by societies around the world, may be adopted faster than some niche commodities. It is also often a good hedge against dollar depreciation. But why would those who can invest in gold exchange-traded funds (ETFs) or own physical gold jewelry buy gold on-chain?

Capital flow velocity is ultimately the killer use case for cryptocurrency.

Tokenized gold moves between markets much faster than gold bars. They are composable, making it much easier to use them as collateral for lending. If a lending market exists, traders could potentially cycle-buy on-chain gold using leverage, just as they do in DeFi.

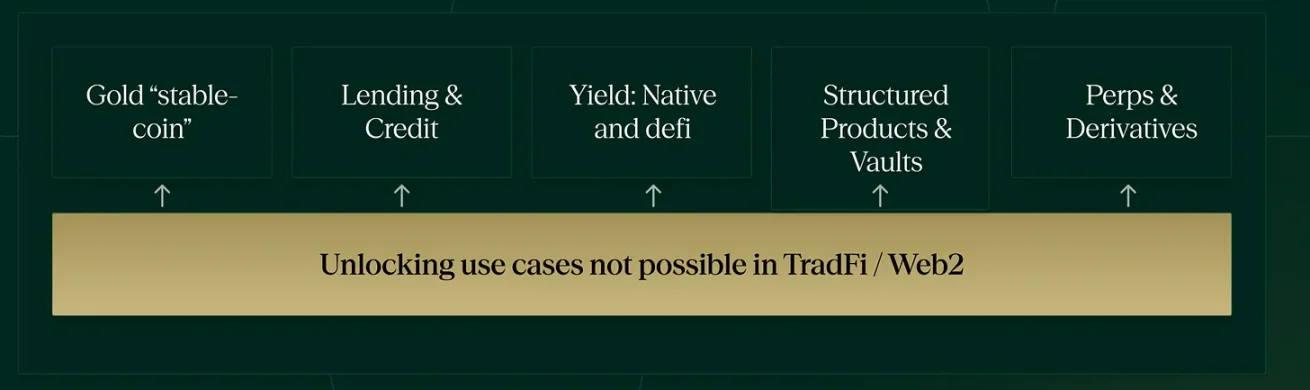

Commodities like gold will also have a stable buy-side, although it may be inefficient in the early stages due to the presence of a sufficiently large traditional market to price it. This is different from tokenized real estate or startup equity, as gold's pricing is consensus-based and does not rely on the nuances of specific geographies or industry preferences. Usman explained its role in Web3 through the image below. His core point is that any on-chain representation of gold must be better than its Web2 counterpart to be relevant.

Usman believes in several ways gold can be utilized in Web3.

Remember I mentioned the correlation between capital flow velocity and fees? This becomes particularly interesting in the context of gold. If a platform (like Orogold) can charge a small basis point fee on each individual gold transaction, they are effectively generating revenue from gold. This could also be reflected in the fees associated with minting and burning gold tokens. In the traditional world, this does not happen because the trading fees of ETFs belong to the issuer or the exchange. Of course, you can lend gold to specific institutions for a return, or your bank might offer such services, but can individuals in emerging markets access such opportunities? I doubt it.

Tokenizing commodities like gold also means that individuals in high-risk markets will have the option to hold related financial instruments without losing control. It also means a person can transfer these financial instruments around the world with the click of a button. This may sound far-fetched, but think about it: nowadays, anyone can go to a country and find someone to exchange their stablecoins for local currency. If gold were tokenized, the same could happen. Or that person could simply exchange their on-chain gold for stablecoins.

Tokenizing commodities (like gold) is not just about asset allocation or trading; it is also about unlocking higher capital flow velocity to generate returns. When fintech applications (like Revolut or PayPal) provide these financial tools, we will form a new category on-chain. However, challenges remain.

First, it remains to be seen whether the on-chain representation of gold can generate sufficient returns through trading or lending to meet user demand.

Second, there is currently no large digital commodity platform that has been widely adopted by liquidity hedge funds and exchanges like stablecoins have in recent years.

All of this assumes that these financial instruments carry no risk in custody and delivery, but that is often not the case.

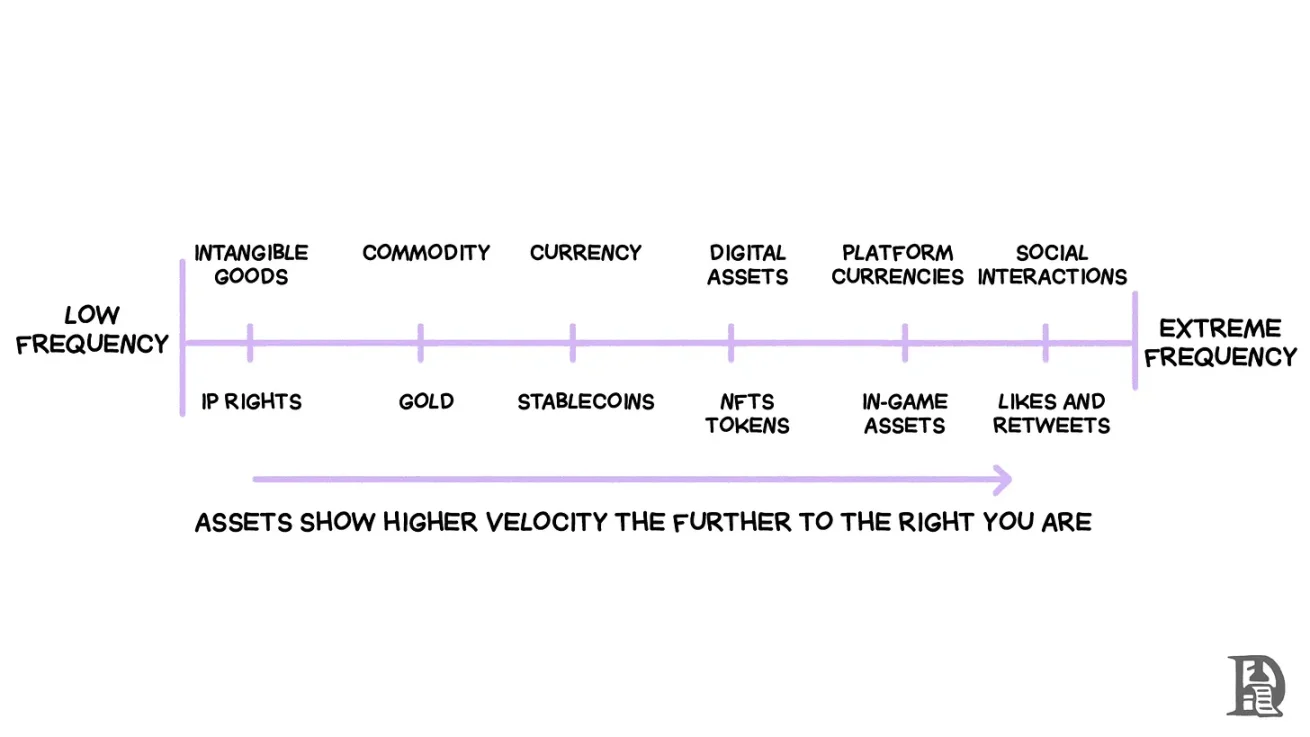

But like most things in life, I am cautiously optimistic about this field. What about things like intellectual property or wine? Well, I don't know. Is there a market that would want to trade wine hundreds of times in a single day? I think not. Even Taylor Swift might not want her music rights tokenized and traded on-chain. The reason is that you need to price things that are best considered priceless. Of course, there may be analysts who can perform cash flow discount analyses on Jay Z's albums and provide numerical values for those songs. But for artists, opening up such a market is not in their best interest.

The chart below should serve as a mental model to illustrate how the trading frequency of on-chain assets will vary under different circumstances.

For things like DeSci or any on-chain intellectual property, it is crucial to have a system that verifies and confirms ownership. In other words, blockchain can be used to verify whether an artwork is authorized and share revenue with the original creator in real-time. Imagine if Spotify paid artists based on the number of plays at the end of each day. Or if our articles were translated into Chinese and we were paid daily based on the traffic they attracted. Or a decentralized autonomous organization behind a drug research project receiving proportional rewards based on the sales of the drug that day.

These types of goods can also command high fees because verifying whether a business has the rights to conduct the necessary transactions is complex. This has yet to be realized, as legal developments take time. But in a world where content is generated by large language models and research stagnates, it is quite possible that we will use basic on-chain elements to verify, reward, and promote the co-creation of intellectual property.

In other words, cryptocurrencies as payment channels will serve one of three roles: transferring funds faster (increasing capital flow velocity); rewarding and recognizing users (verification); or generating returns from idle assets like stablecoins and on-chain gold. Excellent companies can almost always crack two of these three elements, gaining an advantage in revenue within Web3.

When Scenario-Driven Trading Occurs

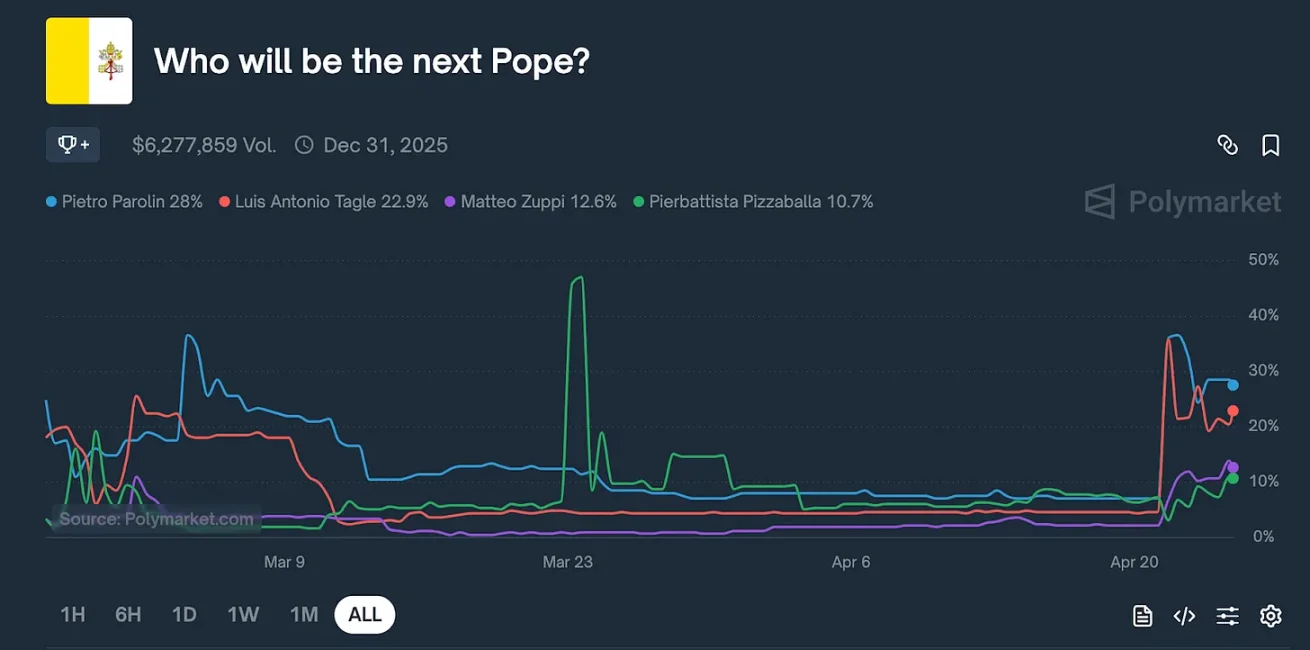

It’s time to profit from years of tracking church politics… on Polymarket.

At the beginning of the article, I described the web as a vast digital marketplace where there are no means of transaction. Blockchain has changed that. We are in a market that exists to facilitate transactions through a shared global ledger. Most of the time, meme assets are issued in response to news events. Polymarket has become the preferred way to conduct predictive analysis on real-world situations. Imagine if someone thinks a person from India might become the next pope? You could create a market for that and place bets on it.

Historically, there has not been a capital factor behind the media and most of our social interactions. At least not in the sense that you are immediately compensated for performing well. You do possess social capital, which brings benefits from being perceived as kind and friendly, along with various opportunities that come with it. Social media has turned our existence into a perpetual performance. This is partly why on-chain media enthusiasts like to turn everything into a mintable form. This way, people can sell digital assets (like NFTs) and profit.

But there may be a middle ground. As the cost and time required to transfer funds decrease, every interaction on the web becomes a transaction. Your likes, clicks, scrolling, and even direct messages (DMs) could be compensated with a token that has no intrinsic value but can attract attention.

The evolution of the web is a history of the attention economy transforming into capital markets while disrupting intermediaries.

Social media protocols like Farcaster can play a role in this, as can faster networks like Monad and MegaETH. The chapters of this story are still being written. But one thing is clear: for early founders, knowing how to balance value capture and capital flow velocity is the key to survival. If you do not know how to sustainably monetize your one million users, then having that many users is meaningless.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。