Author: Uncomprehendable SOL

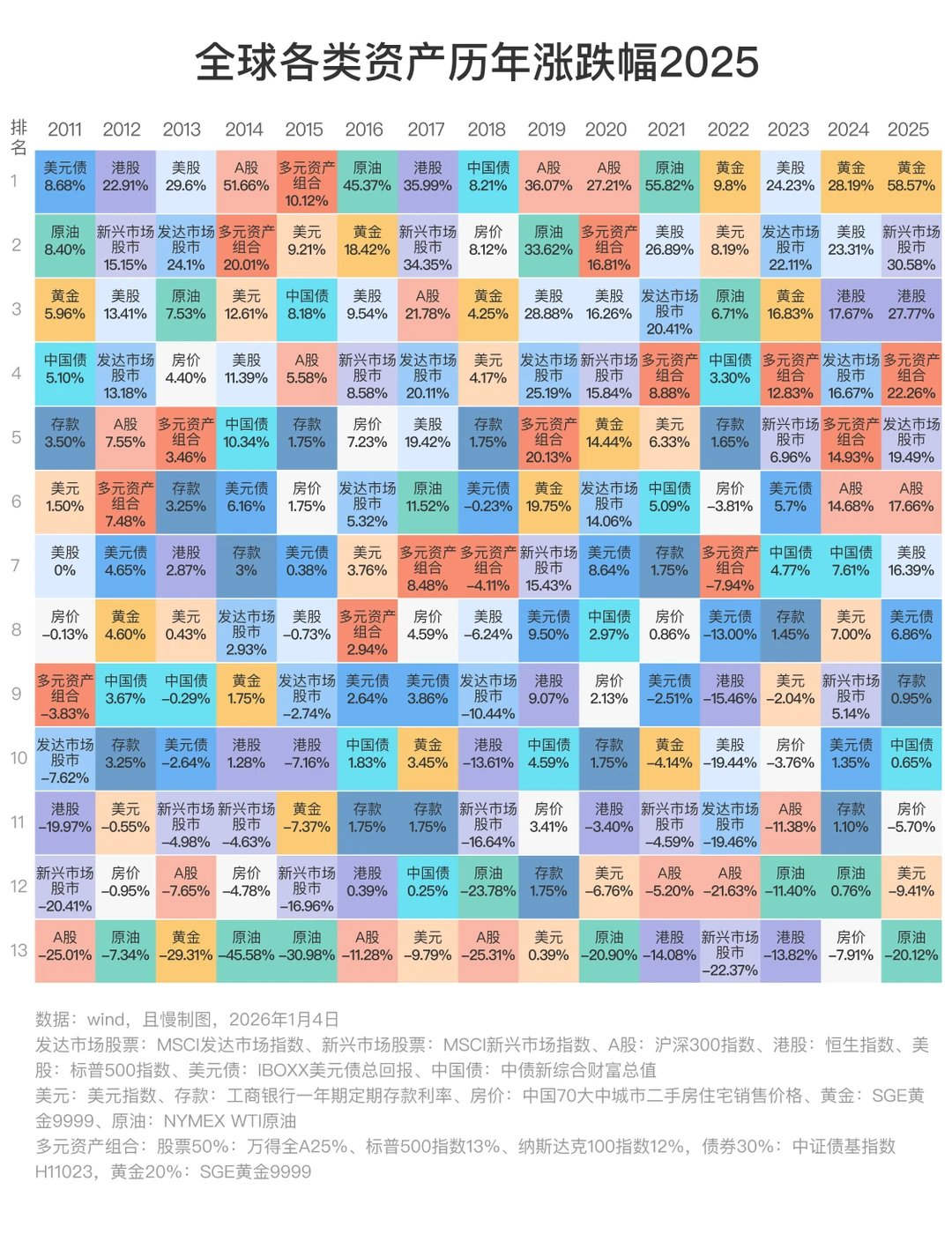

After losing 20 million, I finally understood that to escape the peak in A-shares, the probability of bottom fishing in U.S. stocks, and investing in A-shares, the most important thing is to escape the peak; in investing in U.S. stocks, the most important thing is to bottom fish.

Escaping the peak in A-shares, especially escaping a major peak, is both the easiest and the most difficult. The reason it is said to be easy is that the peak in A-shares is typically characterized by a clamor of voices, and looking back afterwards, it almost writes the two words "major peak" on the candlestick chart;

The reason it is difficult is that one can only make money in A-shares by going long, and the stock market tends to rise over the long term, thus escaping the peak is equivalent to locking in profits, which in itself does not make money, and human nature is inherently greedy.

In comparison, the most important thing in the U.S. stock market is bottom fishing. Looking at the market over the past 20 years, the most important investment rule has been to buy whenever there is a dip.

To put it simply, if the money already invested is simply held continuously, the key is when the new incoming money will bottom fish? In investing in U.S. stocks, the easiest and the most difficult aspect is also bottom fishing.

It is said to be easy, bottom fishing in U.S. stocks is "buy small on small dips, buy big on big dips, don't buy when it doesn't dip"

Since 1776, all bets against the United States have ended with their owners suffering a disastrous defeat.

The reason it is most difficult is that most people transition from "bottom fishing halfway down" A-shares, having the "bottom fishing PDST syndrome", always wanting to fish for lower prices to give themselves some safety protection, which results in them not daring to bottom fish when prices drop, and chasing after rebounds instead.

Therefore, when bottom fishing opportunities arise in U.S. stocks, everyone must clarify two questions:

1. Under normal circumstances, how much does the U.S. stock market drop in a round of adjustment?

2. If a black swan event occurs, leading to endless declines, what should be done?

1. How deep is the adjustment in U.S. stocks? First, we need to unify the definition of what "adjustment" is.

Adjustments are generally classified into three levels: daily, weekly, and monthly, and a downturn must satisfy either one of the two conditions of amplitude or time (everyone's definition may differ; this article represents only my standards).

- Daily level: A decline of more than 5% from the highest point, or a duration of over two weeks (referring to the time span from the highest to the lowest point);

- Weekly level: A decline of more than 10% from the highest point, or a duration of over four weeks;

- Monthly level: A decline of more than 15% from the highest point, or a duration of over four months.

As long as one of the two conditions is met, there are some adjustments that may not be deep but last for a long time, while others are the opposite. Once the definition is clear, bottom fishing is simply about two goals:

- Goal one: buy the position you want

- Goal two: buy as cheaply as possible,

The market always looks clearer in hindsight; during a confusing adjustment phase, we can only determine two things—how much has it dropped from the previous highest point to today, and how many days has it been?

The market could either continue to decline, stabilize, or rise again.

Therefore, there is a contradiction between these two goals; if you buy too quickly, you may achieve goal one but buy at a relatively high price;

However, if you are solely focused on buying cheaply, you may ultimately miss out and see prices rise.

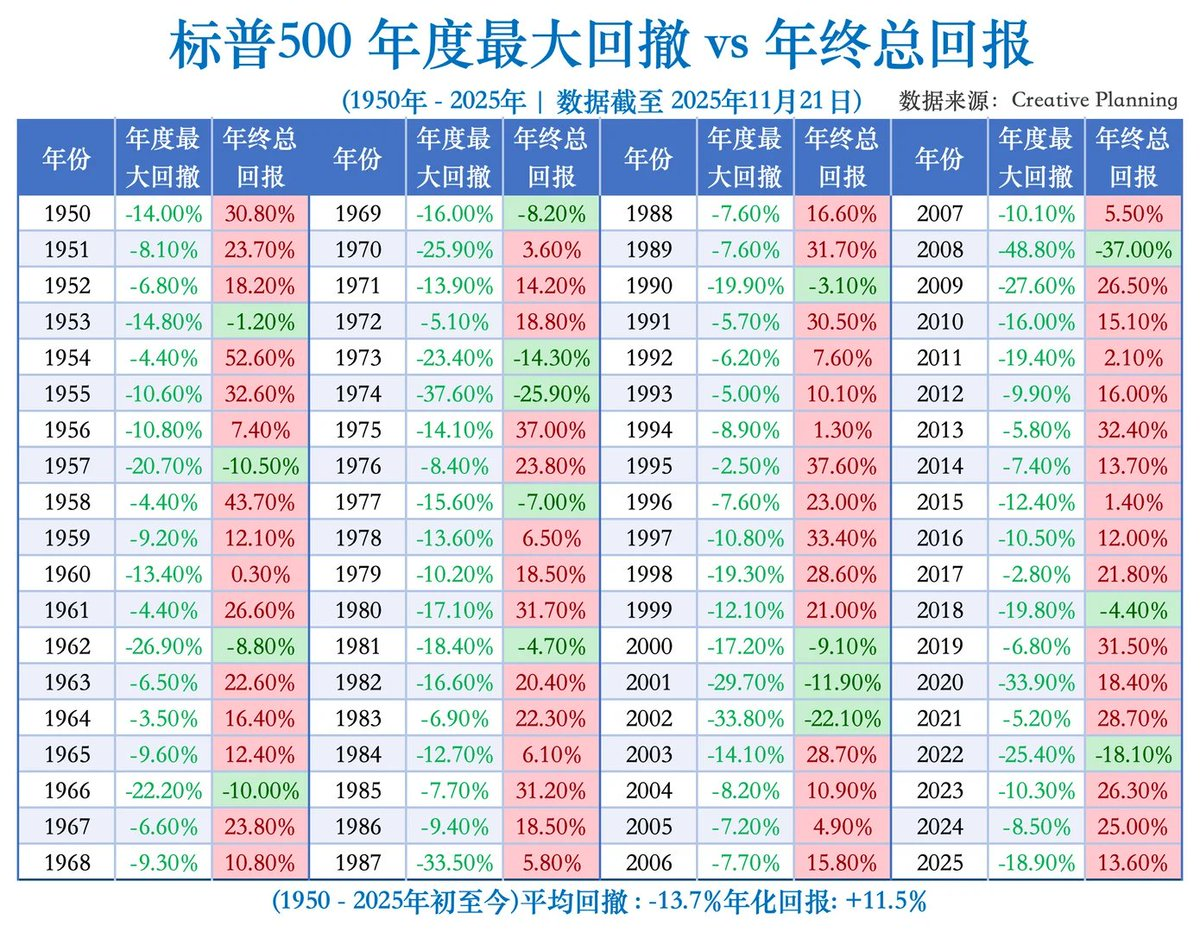

This requires us to have some probabilistic understanding of the historical adjustment amplitudes of U.S. stocks in order to formulate a reasonable target.

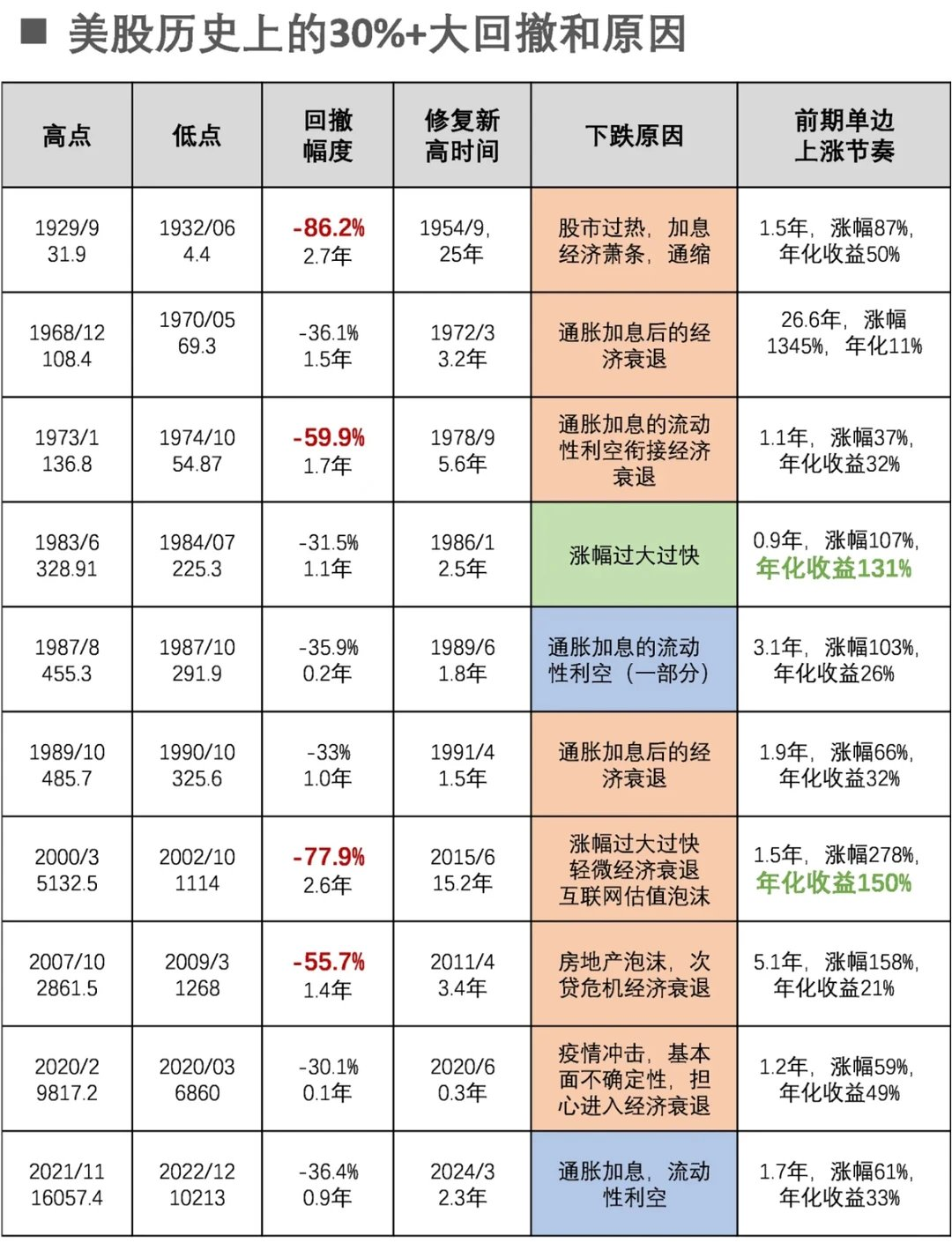

Historical 30%+ large retracements in U.S. stocks and their causes

Taking the S&P 500 index as an example, there have only been 7 monthly adjustments from 2004 to now in the past 20 years, with the reasons being:

- 2022.1-10: the most severe interest rate hike cycle in 40 years

- 2020.2-3: global public health event

- 2018.9-12: trade war compounded by interest rate hikes

- 2015.7-2016.2: central economic recession compounded by interest rate hike expectations

- 2011.4-9: deepening European debt crisis

- 2010.4-6: European debt crisis and Goldman Sachs fraud scandal

- 2007.10-2009.3: subprime mortgage crisis

Thus, monthly adjustments in the U.S. stock market are very rare, averaging one every three years, each with macro fundamental reasons, and there were no adjustments at all from September 2011 to July 2015—definitely a strong bull market.

On the other hand, weekly adjustments occur a bit more frequently, with 2 to 3 instances each year, and they do not require fundamental reasons; whenever there is excessive gain, a correction may occur.

Therefore, the first step in bottom fishing is to determine whether this is a weekly level adjustment or a monthly level adjustment.

However, stock movements are affected by various new information, making it difficult to predict accurately; the Federal Reserve is not yours to control, and bad and good news won't arrive according to your plans—fortunately, you can still set your own goals.

You need to think about a question, imagine this as bargaining with a vendor: if you could only choose one between "buying" and "buying cheaply," which one would you choose?

If it's the former, you should assume the adjustment is at the weekly level for planning, so that even if there is a monthly level adjustment, you can still achieve your first goal; conversely, if your goal is "buying cheaply," you should prepare a bottom fishing plan based on a monthly level adjustment.

However, generally, I recommend everyone prioritize "buying" as the first goal, especially when you have spare cash; firstly, because monthly level adjustments occur once every three years, which is indeed not high probability; secondly, when you have spare cash and cannot buy U.S. stocks, you are quite likely to buy other high-risk products.

With a goal in place, the plan becomes much simpler.

2. Time Plan and Position Plan: When should U.S. stock market bottom fishing initiate?

Taking bottom fishing during a weekly adjustment as an example, as long as there are no new highs for two weeks, a daily level adjustment has effectively occurred, and a bottom fishing plan for the cycle adjustment should be prepared.

The core of bottom fishing in U.S. stocks is two words—phased purchases.

There are two types of phased plans: one is a time-phased plan, which buys once at certain intervals, and the other is a position-phased plan, which buys once it drops to a certain position. Based on the past 20 years of trends, the average time from high to bottom during a weekly adjustment (excluding monthly adjustments) is 10 weeks, thus, the time-phased buying can be divided into three phases, purchasing once every three weeks starting from the peak, with the second buy spaced longer from the first;

Position phased purchases can also be divided into three phases, buying a batch when the price drops 3%, and if the maximum drop reaches 10%, the entire bottom fishing plan can be accomplished.

The probability of completion between these two plans differs; time plans usually can be fulfilled unless it is merely a daily level adjustment that quickly establishes new highs, which isn't regrettable, as it at least seizes an opportunity to add positions during a daily level adjustment.

However, the positional phased plan doesn’t necessarily work out; many weekly adjustments in U.S. stocks may last long but don’t drop to 10%.

Therefore, with a weekly level adjustment, "completing the bottom fishing" should be the first target, which means prioritizing "time phased buying," and implementing the phased bottom fishing plan once the adjustment time arrives, even if the decline has not reached expectations.

When we look at bottom fishing plans targeting monthly level adjustments, the average time to reach the bottom lasts around 6.5 months, but greatly varies, so one should hold the belief of "high probability of not getting it all" while adhering to the principle of buying as much as possible.

Positions don’t need to be averaged but should be staggered, with the three phases being 1/2, 1/3, and 1/6 of the whole plan respectively.

The time plan can be phased: the first month, the third month, the sixth month; the position plan can be phased: drop 3%, drop 8%, drop 15%. Thus, many times when you target "monthly level" adjustments, you may ultimately execute a bottom fishing plan for a weekly level adjustment, but quantity may not suffice, which is why I initially recommend prioritizing the weekly adjustment plan as much as possible.

Bottom fishing in U.S. stocks can be simply summarized into three musts and three must nots:

1. One must make phased plans, and not make random decisions or impulsive trades during the trading day;

2. Prioritize "buying enough" while considering "buying cheaply" as a secondary goal;

3. Focus on "time phased buying" while using "position phased buying" as a supplemental plan. Bottom fishing in U.S. stocks is a very mechanical plan, while U.S. stocks' long-term upward trend and relatively low volatility are the prerequisites for this bottom fishing plan.

However, stocks ultimately remain a place of human nature's tug of war, and the economic operation itself also has unpredictability; black swan events can happen at any time and inevitably will occur.

If the time or depth of the adjustment exceeds the plan, how should one respond? What should be done in the event of a black swan incident?

3. Black Swan Events

The adjustments above are categorized by monthly and weekly levels, which provides clear standards; however, even among monthly adjustments, the differences can still be quite significant. Notably, the events of 2008 and 2020 were actual economic crises rather than mere stock market adjustments.

Thus, we can further classify market adjustments into three types based on their causes:

1. Natural adjustments caused by excessive cumulative gains, but with generally positive macro fundamentals—most daily and weekly level adjustments fall into this category.

2. Adjustments caused by overly high valuations plus economic recession or a shift to loose monetary policy—a minority of weekly and the majority of monthly level adjustments belong to this category.

3. Economic crises or severe recessions caused by systemic risks—a few monthly level adjustments, or long-term bear markets fall into this category.

In the past 20 years, the subprime mortgage crisis in 2008 and the public health event in 2020 both belong to the third category; the former dropped 58% over more than a year, and the latter fell 35% in just two months. Thus, this third category surpasses our bottom fishing plan and requires separate analysis.

However, there is no distinction between a crisis and an adjustment at the onset; when the U.S. stock market first began to decline in 2007, the market believed it was an economic recession. After the Federal Reserve began to cut interest rates, the stock market rebounded, and by early 2008, investors were already rushing to bottom fish.

Therefore, during the bottom fishing process in adjustments, one must continuously observe whether events that did not occur at the beginning of the downturn happen later, or if the factors causing initial declines worsen.

Taking recent instances of deep declines as examples: a standard bear market such as a 27% drop in 2022 is the easiest to judge; it is driven by standard macro logic, where everyone discusses interest rate hikes, and all prices skyrocket; each month brings data telling you this month is worse than last month. Thus, bottom fishing may incur losses at first confirmation, but later you will understand that this is a prolonged battle that requires lengthening the time for bottom fishing.

In contrast, the drastic drop of 36% within a month due to the public health event in 2020 was triggered by an unpreventable black swan event and non-economic factors; in the short term, it was indeed panic-inducing, but once the drop was done, it was finished, and in such circumstances, one can only endure.

The most challenging situation was the financial crisis of 2008, which saw a drop of 58%, which was actually a mixture of the above two cases; within a normal recession, a crisis event caused a deep recession bear market, which is unpredictable, necessitating a response.

Looking further back, the burst of the dot-com bubble in 2000 was a rare sharp decline triggered by excessively high valuations that dragged down the economy; however, the valuation levels at that time were indeed much higher than now and it is considered a discernable gray rhino event, yet no one was willing to "exit the vehicle" first.

In summary of these various U.S. stock downturns, one should not attempt to predict the declines in advance; the most important thing is to face reality and respond only after it occurs; the sky will not fall.

Of course, without forming expectations, timely and correct responses post-incident require you to pay attention to the market; you can't act like financial management by just focusing on allocation without management; you still need to assess whether there is a possibility of evolving into a crisis after it drops to a certain level.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。