Source: decentralised

Written by: Sumanth Neppalli, Nishil Jain

Translation: Shan Ouba, Golden Finance

There are two distinctly different schools of thought in the cryptocurrency space. As a media outlet, we have the privilege of closely observing these two perspectives. One side believes that everything is a market, and pricing is key to achieving transparency; the other firmly believes that cryptocurrency is a superior financial technology infrastructure. Our publishing strategy flexibly adjusts between these viewpoints because, like all markets, there is no single truth — we are simply integrating all possible models.

In this issue, Sumanth will delve into how a new payment standard is evolving online. In short, the core question is: what would happen if articles could be paid for on a per-piece basis? To find the answer, we will trace back to the early 1990s to see what happened when America Online (AOL) attempted to price internet access by the minute; explore how Microsoft prices its SaaS subscriptions; and ultimately focus on Claude's case of pricing conversations by text volume.

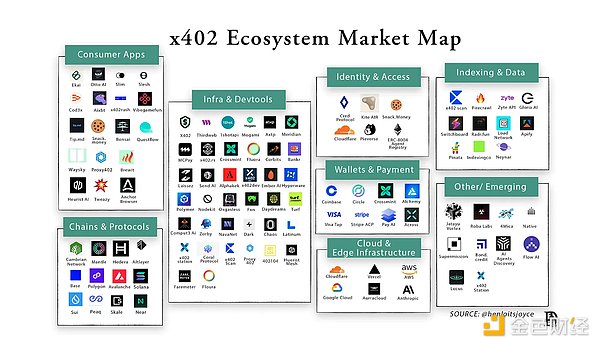

In the process, we will explain the essence of the x402 protocol, its core participants, and its significance for platforms like Substack. The smart agent network is a topic of increasing internal focus for us.

Disconnection Between Internet Business Models and User Behavior

In 2009, Americans visited an average of over 100 websites per month; today, users open fewer than 30 applications on average each month, but the time spent has significantly increased — from about half an hour a day to nearly 5 hours.

Winners (Amazon, Spotify, Netflix, Google, and Meta) have become aggregators, gathering consumer demand, turning occasional use into habitual behavior, and pricing these habits through subscription models.

This model works because human attention follows fixed patterns: we mostly watch Netflix at night, shop on Amazon weekly. Amazon Prime members bundle delivery, returns, and streaming services for an annual fee of $139, eliminating the hassle of frequent payments. Today, Amazon has started pushing ads to subscription users to increase profit margins, forcing users to either watch ads or pay higher fees. When aggregators cannot justify the subscription model, they turn to advertising models, like Google, profiting by monetizing attention rather than user intent.

The Composition of Today's Internet Traffic Has Changed Dramatically:

Bots and automated programs account for nearly half of internet traffic, largely due to the rapid proliferation of artificial intelligence and large language models (LLMs), making the creation of bots easier and scalable.

Of the dynamic HTTP requests processed by Cloudflare, 60% come from API calls — in other words, communication between machines now occupies most of the traffic.

Our current pricing model is designed for pure human use of the internet, but today's traffic is primarily machine-driven and sporadic. Subscription models are based on habitual behavior (listening to Spotify on the way to work, using Slack while working, watching Netflix at night), while advertising models rely on the attention economy (people scrolling, clicking, considering purchases). But machines have neither habits nor attention — they only have trigger conditions and task objectives.

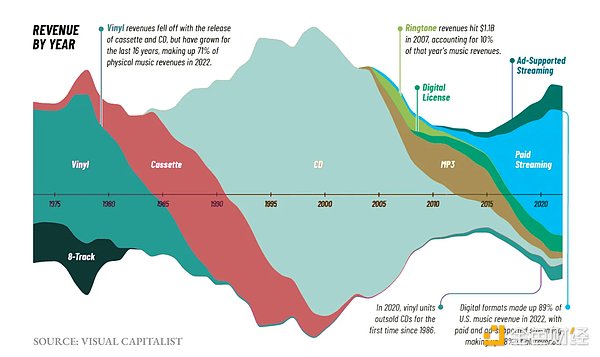

Content pricing is not only constrained by the market but also depends on the underlying distribution infrastructure. The music industry has sold albums for decades because physical media needed to be bundled — the cost of burning one song or 12 songs on the same CD is nearly the same, retailers need high profit margins, and shelf space is limited. In 2003, when the distribution medium shifted to the internet, iTunes changed the pricing unit to singles: purchasing any song for $0.99 on a computer and syncing it to an iPod.

The single format improved the efficiency of music discovery but also eroded revenue — most fans only buy popular songs rather than 10 filler tracks, leading to a decline in per capita income for many artists.

Then, with the advent of the iPhone, the distribution infrastructure changed again. Cheap cloud storage, 4G networks, and global content delivery networks (CDNs) made accessing any song instant and seamless. Mobile phones are always online, allowing users to instantly access an almost infinite library of songs. Streaming services have re-integrated all music at the access level: for $9.99 a month, you can listen to all recorded music.

Today, music subscription revenue accounts for over 85% of the total revenue in the music industry — a fact that Taylor Swift is not pleased with, as she was forced to return to the Spotify platform.

Enterprise software follows the same logic. Because products are digital, vendors can charge based on the actual resources used. B2B SaaS vendors typically offer predictable service access on a "per seat" basis, monthly or annually, and limit features through tiered packages (e.g., $50 per user per month, plus $0.001 per API call).

Subscription models cover predictable human usage, while metered models handle the sporadic usage demands of machines.

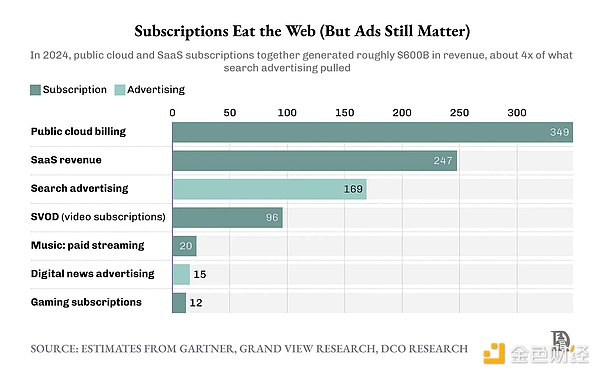

When AWS Lambda runs your function, you only pay for the actual resources consumed. B2B transactions often involve bulk orders or high-value purchases, so the transaction size is larger, and substantial recurring revenue can be obtained from a smaller but concentrated customer base. Last year, B2B SaaS revenue reached $500 billion, which is 20 times that of the music streaming industry.

If most consumption is now machine-driven and sporadic, why are we still using a pricing model from 2013? Because our current infrastructure is designed for humans making occasional choices. Subscription has become the default option because making a decision once a month is more convenient than a thousand micro-payments.

It is not that cryptocurrency has created the underlying infrastructure to support micro-payments (though that is also true), but rather that the internet itself has evolved into a behemoth that requires new pricing methods based on usage.

Why Micro-Payments Fail

The dream of paying a few cents for content is as old as the internet itself. In the 1990s, Digital Equipment's Millicent protocol promised sub-cent transactions; Chaum's DigiCash conducted bank trials; Rivest's PayWord solved cryptographic issues. Every few years, someone rediscovers this clever idea: what if we paid $0.002 per article, $0.01 per song, just paying for the actual value of items?

They all failed in the same way: humans hate measuring their pleasure.

America Online paid a hefty price in 1995 to understand this.

They charged for dial-up internet by the hour. For most users, this was objectively cheaper than a fixed subscription, but customers loathed it because it created a mental burden. Every minute online felt like a timer was running, and every click came with a tiny cost. People would involuntarily view every micro-cost as a "loss," even if the amount was small. Every click became a tiny decision: is this link worth $0.03?

In 1996, when America Online switched to unlimited plans, usage doubled overnight.

People prefer to pay more rather than think more. "Paying precisely for actual usage" sounds efficient, but for humans, it often means anxiety with price tags.

Odlyzko summarized in his 2003 paper "The Case Against Micro-Payments": people are willing to pay more for fixed-rate plans not because of rationality, but because they crave predictability over efficiency. We would rather pay Netflix an extra $30 a month than optimize every $0.99 rental fee. Later attempts (like Blendle and Google One Pass) tried to charge $0.25 to $0.99 per article, but ultimately failed. Unless a large proportion of readers convert to paying users, unit economics do not hold, and the user experience brings cognitive burdens.

Subscription Hell

Isn't life just an endless hassle? Perhaps the gods have also adopted a subscription model for human existence.

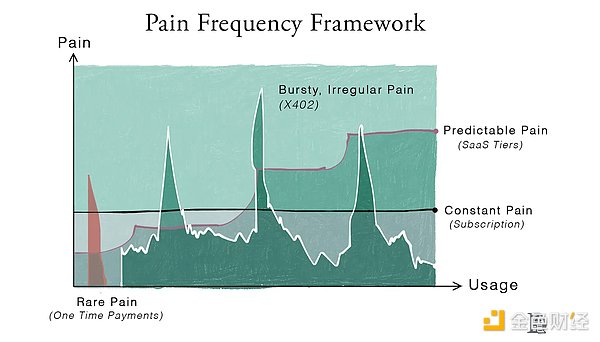

If we crave the simplicity of subscriptions, why are we now complaining about "subscription hell"? A simple pricing reasoning method is: how frequently does the product solve a hassle?

Entertainment demand is infinite. The black line in the chart represents this persistent pain point — an ideal state for both users and companies: a smooth, predictable pain point curve. This is also why Netflix transitioned from a quirky DVD mailing service to an elite FAANG club — it offers endless content, eliminating billing fatigue.

The simplicity of subscription has reshaped the entire entertainment industry. When Hollywood studios saw Netflix's stock price soar, they began to reclaim their film libraries to build their own subscription empires: Disney+, HBO Max, Paramount+, Peacock, Apple TV+, Lionsgate, and more.

The fragmentation of content libraries forces users to purchase more subscription services: to watch anime, you need to subscribe to Crunchyroll; to watch Pixar movies, you need to subscribe to Disney+; consuming content has become a "portfolio building" issue for users.

Pricing depends on two factors: whether the underlying infrastructure can accurately measure and settle usage, and who must make the decision each time value is consumed.

One-time payments are suitable for rare, sporadic events: buying a book, renting a movie, paying for a consultation. Pain points erupt once and then disappear. This model is suitable for infrequent tasks with clear value, and sometimes the pain point itself is desirable — we look forward to the experience of going to the cinema or buying a book at a bookstore.

Accurate measurement of usage ties pricing to work units. That’s why you wouldn’t pay for half a movie (its value is ambiguous). Figma cannot extract a fixed percentage of fees from your monthly output (the value of creation is hard to measure).

Even if it’s not the most profitable way, monthly billing is easier to operate.

Computing resources are different: the cloud can observe usage down to the millisecond. Once AWS can measure execution time with such fine granularity, renting an entire server no longer makes sense — servers are only powered on when needed, and you only pay while they are running. Twilio adopts the same approach for telecom services: one API call, one text message segment, one charge.

Ironically, even in areas where we can measure perfectly, we still bill like cable TV. Usage is measured in milliseconds, but funds flow through monthly credit card subscriptions, PDF invoices, or prepaid "credit limits." To achieve this, each vendor makes you go through the same process: create an account, set up OAuth/SSO authentication, generate API key authorization, bind a bank card, set a monthly limit, and then pray you won't be overcharged.

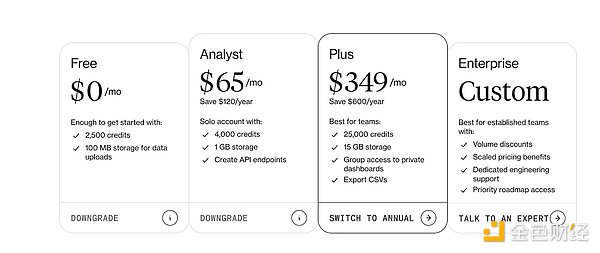

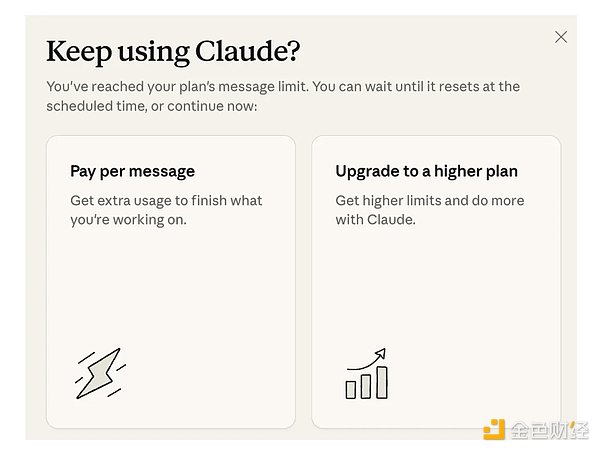

Some tools require you to preload credit, while others (like Claude) restrict you to lower-tier models when you hit your quota.

Most SaaS products fall within the green "predictable pain point" range: too frequent for one-time purchases, yet too stable to require precise per-use measurement. Their strategy is tiered packages — you choose a plan that fits your typical monthly usage, and upgrade when usage exceeds the limit.

Microsoft's "1TB storage per user" limit is an example — it can distinguish between light and heavy users without measuring every file operation. The CFO allocates permissions to limit the number of users needing access to higher-tier packages.

The Confusing Middle Ground

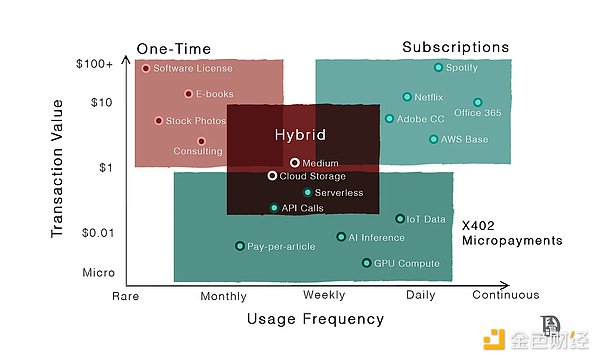

One simple way to classify pricing models is through a two-dimensional chart: the X-axis represents usage frequency, and the Y-axis represents usage variance (i.e., the degree of fluctuation in usage patterns over time for a single user). For example, watching Netflix for two hours most nights is low variance; whereas an AI agent sending 800 API calls in 10 seconds and then stopping is high volatility.

The lower left corner is the one-time payment area: when tasks are rare and predictable, a simple "buyout" pricing model is effective because you only incur the cost once to continue.

The upper left corner is the chaotic "casual browsing web": irregular news binge reading, link jumping, low willingness to pay. Subscription models are too cumbersome, while per-click micro-payments collapse due to decision and transaction friction. Advertising becomes the financing layer, aggregating millions of small, inconsistent views. Global advertising revenue has surpassed $1 trillion, with digital advertising accounting for 70%, indicating that a significant portion of the internet exists in this low-commitment range.

The lower right corner is the ideal area for subscriptions: Slack, Netflix, and Spotify align with human daily habits. Most SaaS products are here, distinguishing heavy users from light users through tiered packages. Most products offer free value-added packages to encourage users to start, then gradually shift their usage patterns from the upper left to the lower right through daily stable habits. Global annual revenue from subscriptions is about $500 billion.

The upper right corner is the focal point of the modern internet: LLM queries, agent operations, serverless burst traffic, API calls, cross-chain transactions, batch jobs, and IoT device communication. Usage is both continuous and volatile. Fixed fees based on seats cannot accurately reflect this reality but lower the psychological barrier to paying — light users overpay, heavy users are subsidized, and revenue is disconnected from actual consumption.

This is why seat-based products are gradually shifting to metered models: retaining the basic plan for collaboration and support while charging for heavy usage. For example, Dune offers a limited credit allowance monthly, with small simple queries priced low, while larger queries that run longer consume more credit.

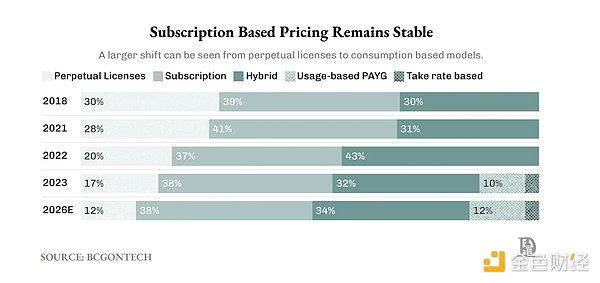

Cloud services have made millisecond billing for computing, data, and API platforms the norm, with the credit they sell expanding with actual workload — revenue is gradually being tied to the smallest observable unit on the network. In 2018, less than 30% of software adopted usage-based pricing; today, that figure is close to 50%, while subscriptions still dominate with a 40% share.

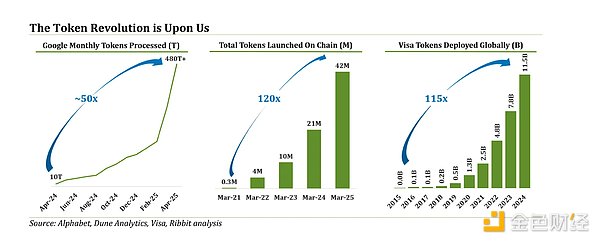

If spending is gradually shifting to a consumption-based model, the market is telling us: pricing needs to align with the rhythm of work. Machines are rapidly becoming the largest consumers of the internet — half of consumers use AI-driven searches, and machine-generated content has already surpassed that created by humans.

The problem is that our infrastructure still operates on annual accounts. Once you sign a contract with a software vendor, you gain access to their dashboard, including API keys, prepaid credit limits, and end-of-month invoices. This is fine for habitual humans, but cumbersome for sporadic software usage. In theory, you could set up monthly automatic billing using ACH, UPI, or Venmo, but these methods require batch processing, and their fee structures do not hold up in sub-cent, high-frequency trading scenarios.

This is where cryptocurrency's significance to the internet economy comes in. Stablecoins provide a programmable, global, sub-cent precision payment method that can settle in seconds, operate around the clock, and be directly held by agents rather than being trapped behind bank interfaces. If usage is event-driven, settlements should be too — and cryptocurrency is the first infrastructure that can genuinely keep pace with this rhythm.

The Essence of the x402 Protocol

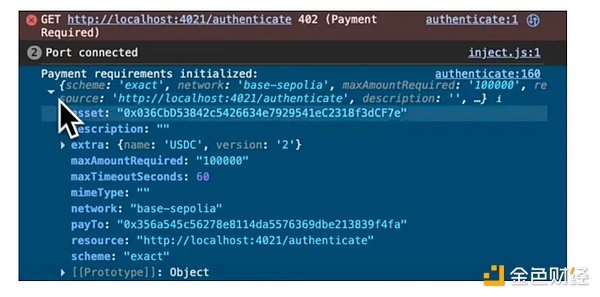

x402 is a payment standard compatible with HTTP, utilizing the 402 status code reserved for micro-payments decades ago.

Essentially, x402 is a way for sellers to verify whether a transaction is complete. Sellers wishing to accept on-chain gas-free payments via x402 must connect to service providers like Coinbase and Thirdweb.

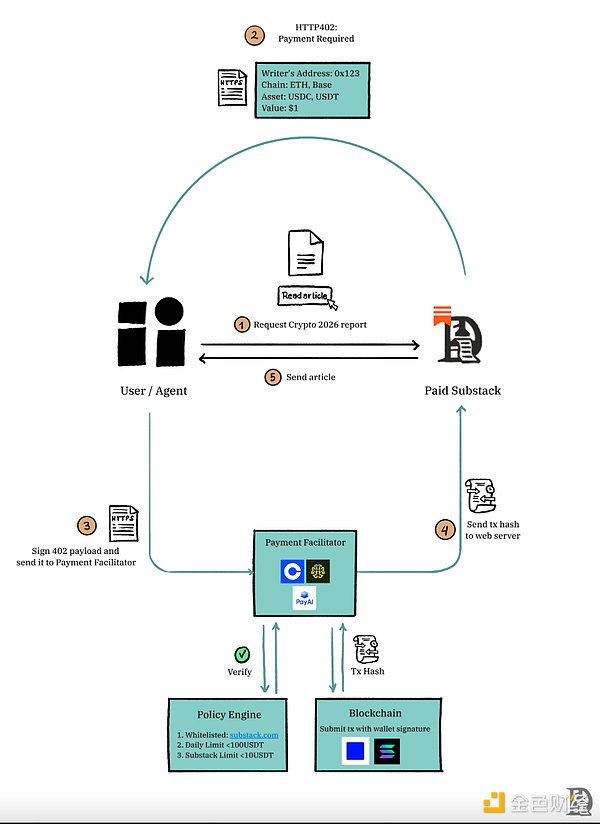

Imagine Substack charging $0.50 for a paid article: when you click the "pay to read" button, Substack returns a 402 code containing the price, accepted assets (like USDC), network (like Base or Solana), and related policies, formatted as follows:

Your Metamask wallet authorizes the payment of $0.50 by signing the message and passing it to the service provider. The service provider puts the transaction information on-chain and notifies Substack to unlock the article.

Stablecoins simplify the accounting process, allowing for settlement at network speed and small denominations without needing to open separate accounts with each vendor. With x402, you don’t need to preload five credit accounts, switch API keys between different environments, or discover at 4 AM that a quota trigger caused a task to fail. Human billing can continue using the most suitable credit card method, while all sporadic machine-to-machine interactions are completed automatically and cheaply in the background.

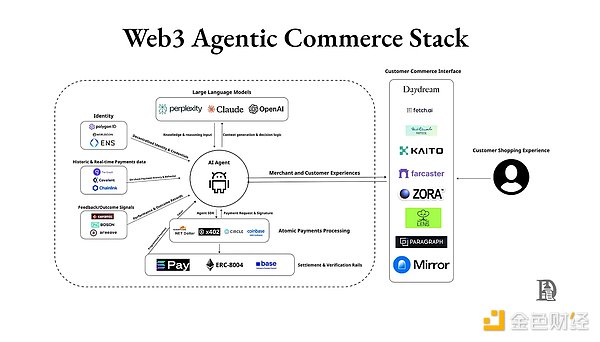

You can feel this difference in the smart agent checkout process. Suppose you try a new fashion style on the AI fashion chatbot Daydream: today, the shopping process redirects you to Amazon so you can pay using your saved card information; whereas in the world of x402, the agent can understand the context, retrieve the merchant's address, and pay directly from your Metamask wallet without leaving the chat interface.

The interesting thing about x402 is that it is not currently a single entity but is composed of layers common in real infrastructure. Anyone building AI agents through the Cloudflare Agent Kit can create bots priced by operation. Payment giants like Visa and PayPal are also adding x402 as supported infrastructure.

QuickNode provides a practical guide on how to add an x402 paywall to any endpoint. The direction of development is clear: unify the "smart agent checkout" function at the SDK layer, making x402 the way for agent payment APIs, tools, and ultimately retail procurement.

Integrating the x402 Protocol

Once the network supports native payments, an obvious question arises: in which areas will it first become popular? The answer is high-frequency usage scenarios with transaction values below $1 — in these scenarios, subscription models charge light users excessively (the minimum monthly subscription fee becomes a barrier). As long as blockchain fees are feasible, x402 can settle each request at machine speed, with precision down to $0.01.

Two forces make this shift imminent:

Supply side: the explosive growth of "tokenization" of work — LLM tokens, API calls, vector searches, IoT signals. Every meaningful operation on the modern internet has been attached to a tiny, machine-readable unit.

Demand side: SaaS pricing leads to significant waste — about 40% of licenses are idle because finance teams prefer to pay per seat (easy to monitor and predict). We measure work at the technical level but bill humans at the seat level.

Capped event-native billing is a way to align the two worlds without scaring off buyers. We can set soft limits and ultimately settle at the optimal price: news websites or developer APIs can charge per use and then automatically refund to the announced daily cap.

If The Economist sets "0.02 dollars per article, daily cap 2 dollars," curious readers can browse 180 links without doing mental calculations — at midnight, the protocol will automatically settle to 2 dollars. This model also applies to developer platforms: news organizations can charge for each LLM crawl to sustain future AI browser revenue; search APIs like Algolia can charge $0.0008 per query, with a total daily usage amounting to $3.

You can already see consumer-grade AI moving in this direction: when you reach Claude's message limit, it doesn't just say "limit reached, come back next week," but offers two options on the same screen: upgrade to a higher subscription plan or pay per message to complete the current operation.

What is currently missing is a programmable infrastructure that allows agents to automatically make the second choice — pay per request without UI pop-ups, bank cards, or manual upgrades.

For most B2B tools, the actual end state is

"Subscription baseline + x402 burst billing": teams retain a basic plan tied to the number of users for collaboration, support, and daily backend use; occasional heavy computational demands (build minutes, vector searches, image generation) are billed through x402 without forcing an upgrade to a higher tier.

Better network services can also be integrated: Double Zero aims to provide faster, purer internet services through dedicated fiber — routing agent traffic to its network allows for x402 pricing per gigabyte, with clear service level agreements (SLAs) and caps. Agents needing low latency for transactions, rendering, or model jumps can temporarily switch to a fast lane, paying for specific burst demands before switching back to the normal lane.

The SaaS industry will accelerate its transition to usage-based pricing models but will set up safeguard mechanisms:

Lower customer acquisition and activation costs: revenue can be generated from the first call, with temporary developers who never complete the OAuth or card binding process still able to pay $0.03 to use the service; agents are more inclined to choose vendors that allow immediate payment.

Revenue grows in sync with actual usage rather than relying on seat expansion: this will address the issue of 30%-50% of seats being idle in most enterprises, shifting core billing to capped burst usage scenarios.

Pricing becomes a competitive advantage at the product level: "pay an extra $0.002 per request for the fast lane" "bulk mode at half price" — startups can enhance revenue through such flexible pricing experiments.

Lock-in effects weaken: users can try vendors without complex integrations and time investments, lowering switching costs.

A World Without Ads

Micro-payments will not completely eliminate advertising but will narrow the scope of advertising as the only viable model. Advertising will still perform well in "casual intent" scenarios, while x402 will price scenarios that advertising cannot cover — occasionally, users may be willing to pay for a quality article without subscribing to a monthly plan.

x402 reduces payment friction and may change the industry landscape once it reaches a certain scale:

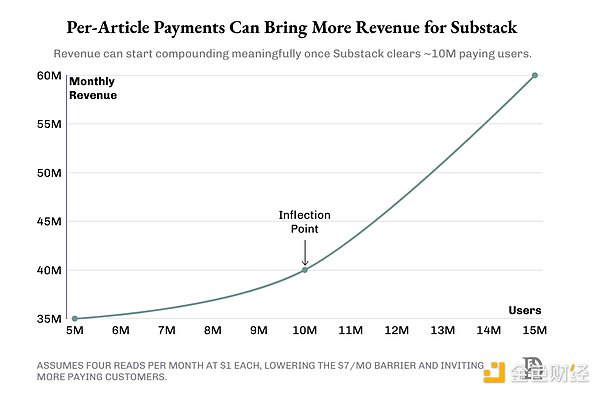

Substack has 50 million users with a conversion rate of 10%, meaning 5 million paying subscribers, each paying about $7 per month. When the number of paying subscribers doubles to 10 million, Substack may gain more revenue from micro-payments — lower friction will lead more casual readers to switch to pay-per-article, accelerating the revenue growth curve.

This logic applies to all sellers of "high variance, low frequency" sales: when people use a product occasionally rather than forming a habit, paying per use feels more natural than a long-term subscription.

It's a bit like my experience playing badminton at a local court: I play two or three times a week, usually with different friends at different venues. Most courts offer monthly memberships, but I prefer not to be tied to a specific venue — I like the freedom to choose which court to go to, how often to go, and to skip when I'm tired.

Of course, I know this varies from person to person: some prefer to go to the nearest court, some enjoy the habit enforcement that subscriptions bring, and some may want to share memberships with friends.

I can't comment on offline payments, but through x402, this personalized demand can be reflected in the digital world. Users can set their payment preferences through policies, and companies can offer flexible pricing models to accommodate everyone's habits and choices.

The true shining scenario for x402 is in smart agent workflows. If the past decade was about transforming humans into logged-in users, the next decade will be about transforming agents into paying customers.

We are already halfway there: AI routers like Huggingface allow you to choose among multiple LLMs; OpenAI's Atlas is an AI browser that uses LLMs to perform tasks for you; x402 serves as the missing payment infrastructure integrated into this ecosystem — it enables software to settle small bills with other software at the moment work is completed.

However, having infrastructure alone is not enough to constitute a market. Web2 has built a complete support system around bank card networks: banks' KYC verification, merchants' PCI compliance, PayPal's dispute resolution, card freezes for fraudulent transactions, and refund mechanisms when issues arise. Smart agent commerce currently lacks these safeguards. Stablecoins + HTTP 402 allow agents to pay, but they also remove the built-in recourse that people take for granted.

When your shopping agent buys the wrong flight, or your research bot exceeds the data budget, how do you recover the funds?

This is precisely the question we will delve into next: how developers can use x402 without worrying about potential failures in the future.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。